Talking with photographer and painter Nick Waplington is akin to viewing and pondering his work. There is a lot of information to sort through. But if you can find some order in the onslaught of ideas, or the “chaos” as he likes to call it, you will find a perspective wildly and almost enviably unique. The subjects of his conversation are as varied as those within his photographs and his paintings. While Waplington’s work has dealt with environmental concerns, rave culture, the creative processes and inner struggles of the late Alexander McQueen, and (as in his paintings) his own inner monologue, a 40-minute conversation with Waplington darts around discussions about his creative process, international politics, the contemporary art world and the business surrounding it, and even skateboarding.

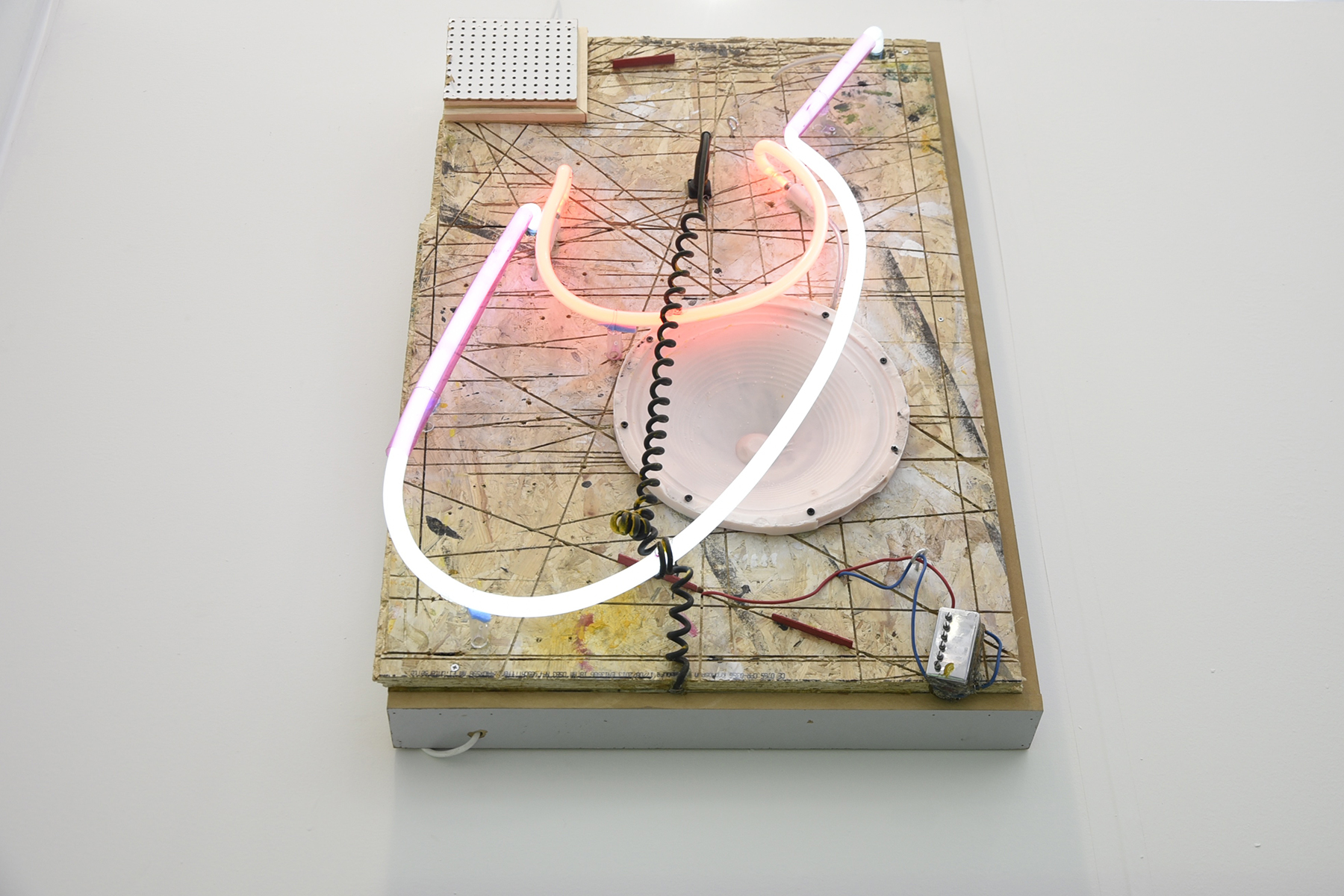

It’s sometimes difficult, as a journalist, to dilineate between being a journalist and a fan. And I am a super fan of Nick Waplington. He was one of the photographers that radically altered my perceptions of the form, and it was difficult to not lean all my questions towards his photographic practice even when now his paintings are a large part of his artistic output, especially with his incredible exhibition of recent paintings at These Days gallery in Los Angeles entitled, ‘A Display of Panic in a Moment of Absolute Certainty.’ In that, it’s important to note that Waplington is not simply, “Nick Waplington the painter,” or “Nick Waplington the photographer,” but that he is “Nick Waplington the artist.” All the mediums he works in (also including video, computer-generated imagery, sculpture, and found material) become part of a cohesive, if almost manically diverse, body of work. While his photos reveal an almost poetically chaotic point of view on Waplington’s external world, his paintings offer the viewer a look inside his internal world allowing us to examine his beliefs, thoughts, and emotions. “I’ve been making art daily since I was 15-years-old.” Now, I’m nearly 51,” says Waplington. Ultimately, what you get is this large body of work that progresses. A lot of artists, especially photographers, have a short phase. To stay fresh, and to not make the same work over and over, is a challenge.”

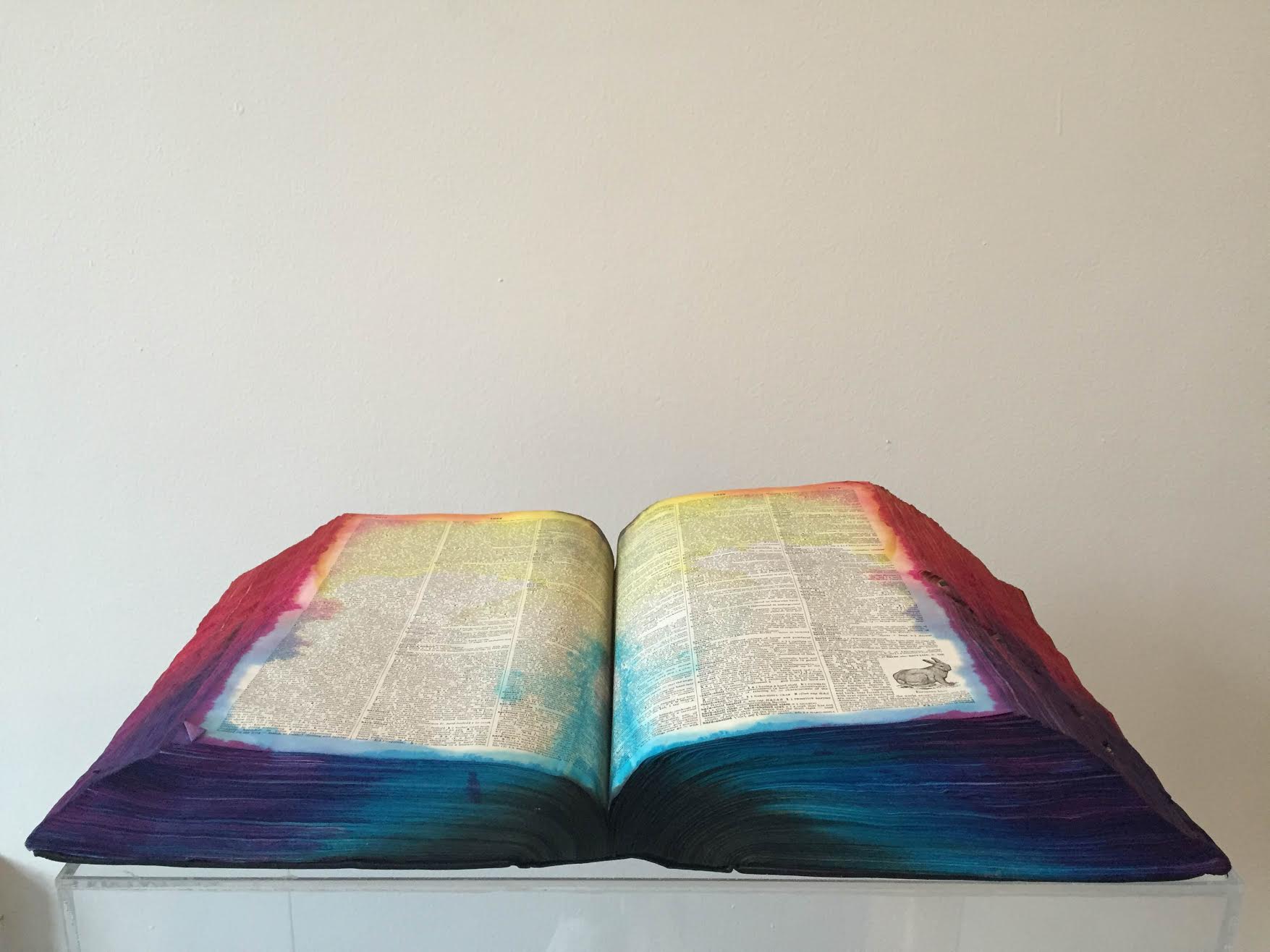

The These Days exhibition is a result of Waplington living in Los Angeles for the past year and devoting his entire practice to painting. As with his photography, the paintings are sensitive to the environment that Waplington created them in. They are exploding in color and contrast, mimicking the city’s consistently beautiful weather in the face of global climate challenge. There is a glorious randomness to the imagery, almost as if Waplington finds himself searching for beauty amidst cultural marginalization Waplington and I caught up via Skype while he was at a skate park in England with his son.

NICK WAPLINGTON: This is the only spot where I can get Wifi in the skate park.

LEHRER: Are you skating right now?

WAPLINGTON: Yeah, I’m skating with my son.

LEHRER: That’s fantastic. I wish my dad skateboarded with me. He was always trying to get me to golf, and then would get frustrated when I couldn’t make the shot.

WAPLINGTON: [Laughs.] It’s a nice day here.

LEHRER: I’ve been looking at your paintings, and they’re beautiful. First, I was really curious, do you feel like you artwork is reflective of the environment you created it in? I ask because I felt like your early photographs had this chilly, muted feel to them. While your paintings, which were primarily done in Los Angeles, were more bright, exploding in color and contrast. Is that at all accurate?

WAPLINGTON: Well, these are not the first paintings I made, but I can’t help but be affected by [the LA] kind of environment. The light really influenced my time in LA. I have an outdoor studio that I enjoy painting in. I’ve been immersed in painting since I’ve been in LA. There’s a flow [to my paintings]. Ideas move from one painting to the next. Everything is a progression like that.

LEHRER: And you like Los Angeles?

WAPLINGTON: Yeah, yeah. I’ve lived there before, so for me, it’s very easy to get back to where I left off.

LEHRER: Do you feel like you’re the type who can find something to love about every type of place you go?

WAPLINGTON: Yeah. I find everything interesting. Being in different places for long periods of time - I really feed off that. In my life, I’ve spent extensive periods in Sao Paolo, Zurich, Los Angeles, Sydney, London, New York… I’ve used that as a catalyst for making work. It’s always good to throw everything up in the air every once in a while, you know?

LEHRER: Absolutely. One thing I’ve found most compelling in your work is that there always seems to be, at least to me, a central conflict driving it. With the McQueen photos, there was this contrast between this masterful artisan at work and a guy struggling with exhaustion and massive expectations. With West Bank, there were obvious political conflicts inherent in that region. Are you purposefully looking for these conflicts?

WAPLINGTON: I have all sorts of problems. I certainly wouldn’t want to do therapy to straighten myself out. I deal with my own personal edginess. Often, within my work, there’s a kind of autobiographical stream to it. All the projects – including McQueen, to a certain degree – were characters similar [to me] in some respects. The title of the McQueen book refers to my working process as much as his.

LEHRER: I feel like that’s why you’ve been so successful. Your subjects are so varied, in painting and photography. But they all feel a part of one, definitive vision. Is that something that you strive for?

WAPLINGTON: Yeah. I’m always trying to order out some chaos. I’m not an artist that has one thing. I can’t really understand that limited scope. “I’m a geometric artist… I’m a body artist…” You know? I’m always looking for the next thing – reading, meeting people and finding new things to make work about.

LEHRER: I feel like it’s almost implemented by the industry. Even on the media side of things, I like to write about everything – music, art, news, fashion, whatever. But I have editors that will tell me to stay in my lane, to pick one thing and focus on that. I can’t imagine ever writing about one thing.

WAPLINGTON: That’s the problem with the galleries. They want artists who are known for a type of work. Collectors want to collect a type of work. There’s a narrowing of perspective. It makes it harder to sell work. But in the long term, it makes the work much more interesting. I haven’t allowed my work to be defined by people other than myself.If people like it, they like it. If not, it’s okay.

LEHRER: So it’s not Nick Waplington, the Photographer AND Nick Waplington, the Painter? It’s just Nick Waplington, the Artist?

WAPLINGTON: I just see it all as my work. I don’t need to separate things.

LEHRER: I feel like These Days was an appropriate gallery choice in that way because they do anti-establishment stuff. Your work’s core has a sense of, “I’m going to do what I want.”

WAPLINGTON: It’s not a gallery that’s functioning in the art world, as such. It’s basically a space where they put on shows that they like. It It was interesting to take over the space and use the space as functioning for the art world, even though it’s not known for having art world shows. We like that. I like that side of Downtown. I’ve been interested in Downtown [Los Angeles] since the late 90s when I was living in Eaglerock. I was going to a lot of rave parties down there at that point.

LEHRER: Yeah, for sure. LA, at that time, was really defined by skateboarding and surf culture.

WAPLINGTON: That’s changing too. But all these new concrete skateparks are popping up. I try to get to Glendale skatepark whenever I get a moment. At my age, if you want to keep skating, you have to skate.

LEHRER: I see some of these guys, like Andrew Reynolds, frontside flipping twenty stairs at age 38. How are his knees not collapsing right now?

WAPLINGTON: I saw a video of a 55 year old Lance Mountain kickflipping a table. It’s crazy.

LEHRER: I don’t want to get too off on a tangent, but I remember when I was really into skateboarding in the early 2000s, and the first Flip video came out. I remember thinking, “This is the best that skateboarding is ever going to be.” I watch a video now, and the kids who are skating now are sorcerers.

WAPLINGTON: Yeah. But you have a generation of kids who are growing up with concrete skateparks. My son is 11, and he’s here every day he can be here. Obviously, they’re going to be doing all sorts of shit that wasn’t possible 10 or 15 years ago.

LEHRER: I wanted to talk to you about the chaos you refer to in your work. Is this chaos an internal or external chaos?

WAPLINGTON: I am dyslexic and left handed, so everything is slightly chaotic with me. I’m drawn to the fringes of society, in the world in general, but especially in LA. Republican states have been sending all their homeless people on buses to California. I’ve been quite influenced by these very large tent cities that have been growing along the freeways, as you go down towards Long Beach. I’ve been hanging out there and vibeing off that a little bit. I’ve been thinking about how these things compare with the 1940s when people were moving from Oklahoma and Tennessee to California, and they were living in the LA River in tents instead. Somehow, it seems like America is in need of a New Deal again, as you were lucky enough to get with Roosevelt. There’s a strangulation of the economy right now. It doesn’t transpose itself directly into the work, but there’s a psycho-geographical feel to some of the paintings.

LEHRER: It is an interesting time to live in the US. It feels like the US it at a huge crossroads. A good portion of the country wants to move forward – vote for Bernie Sanders, get universal free healthcare, raise the minimum wage. And then there’s this other half that is completely reactionary and places all the blame of minorities and immigrants.

WAPLINGTON: There’s a contradiction in the GOP point of view. They want to bring down the trade barriers that exist between America and the rest of the world, so there is a mobile free trade area. But then they want America to be separatist from the rest of the world and still have the higher stander of living. They don’t want to engage with the rest of the world; they want to use the rest of the world as a production facility. If they’re going to remove the trade barriers, they’re going to have to engage with everyone else. They can’t have it both ways, but they don’t really understand that. It’s interesting times, definitely.

LEHRER: What feels more at peace for you in art? Is it photography or painting?

WAPLINGTON: I like doing both, I really do. Maybe as I get older, I might be out there taking pictures less than I am in the studio. But I’m still taking pictures all the time. I had this book a couple of years ago, the Patriarch’s Wardrobe, in which I combined photograph and painting. Now, I’m making a new body of work that includes some of the paintings in the show. I’m going to combine photos and paintings again. I might add text, too. I’m very much a solo worker. I don’t have a team of people working with me. Everything that’s made by me is really made by me.

LEHRER: I really loved the Brooklyn Museum exhibit you were featured in, ‘This Place.’ I included it an article for Forbes about the best exhibitions of the winter. I got a weird email about it from a publicist. I wrote something about it being political, and she said, “No, no, can you take that out? It’s not political.” I was thinking, “How can anything about the West Bank be not political?” I want to know what your take was on that experience, and if you think politics can be removed from a discussion about The West Bank.

WAPLINGTON: I don’t think politics can be removed, but I tried to make work that wasn’t dealing directly with politics. I wanted to make work that had connectivity and time to it. I wanted my work to be a catalyst for dialogue about the West Bank. I want to make work about Jews in the West Bank that wasn’t about conflict with the Palestinians. It was, “Here is the landscape. Here are the Jewish people. What do you think about that?” The sculptural element was adding the Palestinians into the equation in a hidden way. It reminded me of being in South Africa during apartheid, when they managed to hide black people away somehow. I know that it’s very contentious to compare the West Bank to South Africa, especially amongst Jewish people, but the parallels are there, unfortunately. I am Jewish, you know that?

LEHRER: Yeah, I’m Jewish too. I don’t think, from a moral standpoint, that I can totally condone the hiding of an entire group of people who have lived there forever.

WAPLINGTON: Yeah. It’s just not fair, this collective punishment. I really believe that it would be possible to make a kind of deal that was to everyone’s advantage. I think it’s really doable and possible. There’s this idea that the other group will just go away at some point. It’s ridiculous.

LEHRER: It’s insane to me that Bernie Sanders is our first Jewish presidential candidate. He just said that he would support a two-state deal, and he was called anti-Israel by every publication in the country.

WAPLINGTON: Yeah. Well, the West Bank is the biblical land of Israel. They’re not going to give it up. Let’s be honest about that. I think the two-state solution looks great on paper, but it seems impossible. It’s not going to be split, so it’s about finding a solution with both groups of people within one state, in my opinion.

LEHRER: It does seem like that. The optimist in me wants to think anything is possible, but I haven’t been there.

WAPLINGTON: 25% of the people in Israel are Arab. I just believe that if it’s one state, they might as well incorporate the West Bank, give everyone the vote, and have a constitution that gives people their rights. They can be called Israel and Palestine. Why not? We already have a country with two different populations. Half of Malaysia is Chinese and secular, whereas the other half is Muslim. And they make it work. I think if they do it, after a few years, they’ll be wondering what all the fuss as about.

LEHRER: Once peace is actually achieved, people start to realize, what was the fighting for? This is so much better.

WAPLINGTON: I believe it can be worked out. People think I’m crazy for believing that.

Nick Waplington "A Display of Panic at a Moment of Absolute Certainty" will be on view at These Days LA until June 5, 2016. Text and interview by Adam Lehrer. Photographs by Flo Kohl. Follow Autre on Instagram: @AUTREMAGAZINE