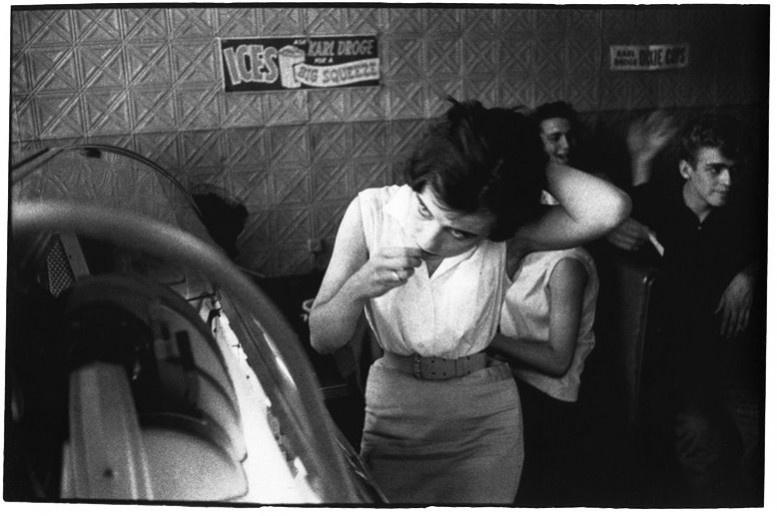

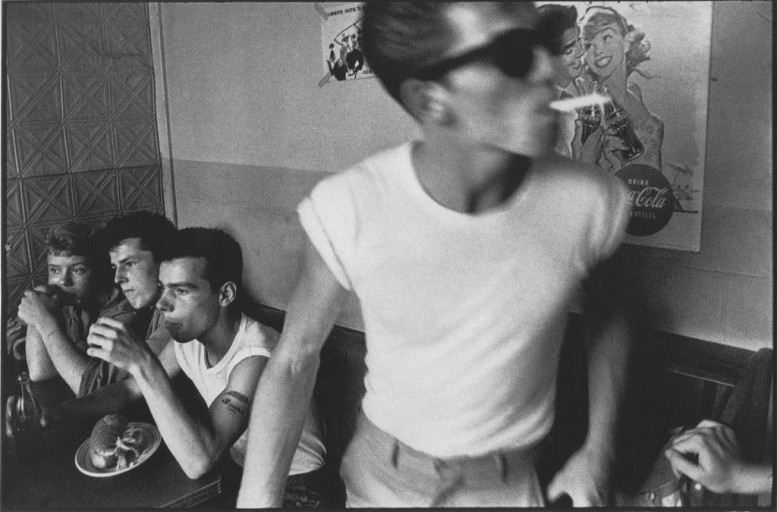

This anthology of photographs was initially conceived as a metaphorical biography, though I now have reservations about that conception. The bias for the dark, the bizarre and the allegorical in the work is my entire fault. For, like Ezekiel in the Bible, I embrace the apocalypse. I can easily blame my mother and father for my obsession with meaning and purpose, and the fact that I find beauty without truth unsatisfactory. Except, I suspect the problem lies elsewhere. It is located somewhere between 1956 and now.

These photographs explore a part of me which I have so far neglected in my work, – my spirituality. There are several reasons why it was ignored: ambivalence, embarrassment, fear of the political and other implications or perhaps the deflection of my gaze. This exhibit is an attempt to come to terms with my schizophrenic existence. The expression I take as a title for this exhibition, "Chasing Shadows" has quixotic connotations in English, but in African languages its meaning is antithetical.

"...while I feel reluctant to partake

in this gossamer world,

I can identify with it."

"Shadow" does not carry the same image or meaning as seriti or is'thunzi. The word in Sotho and Zulu is difficult to pin down to any single meaning. In everyday use seriti or is'thunzi can mean anything from aura, presence, dignity, confidence, power, spirit, essence, status and or wellbeing. The words in the vernacular also imply the experience of being loved or feared. One's seriti / is'thunzi can be positive or negative and can exert a powerful influence. Having a good or bad seriti / is'thunzi depends on the caprice of enemies, witches, relatives both dead and living, friends or associations, and on circumstance or time. Having and defending one's own seriti / is'thunzi from evil forces or attacking the seriti / is'thunzi of one's perceived enemies preoccupies and torments many African people. Those Africans who disdain these notions are at least aware of seriti/ is'thunzi. Especially the elite, when they engage in conversation with white South Africans, they often deny this black African consciousness.

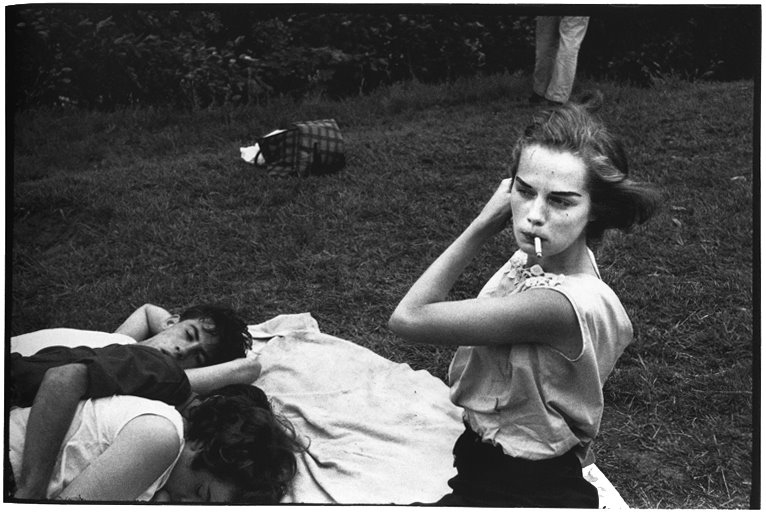

I grew up on the threshing floor of faith. A faith that is both ritual and spiritual – a bizarre cocktail of beliefs that completely embraces pagan rituals as well as Christian beliefs. And while I feel reluctant to partake in this gossamer world, I can identify with it. It does not strike me as 'peculiar'. Yet, I still try to avoid being trapped in its hypnotic embrace, which seems to mock my carefully cultivated indifference and self confidence. I feel ambivalent about my ambivalence, embarrassed at my embarrassment.

This project has steered me to places where reality blended in freely with unreality, where my knowledge of the photographic medium was tested to the limit. While the images record rituals, fetishes and settings, I am not certain that I captured on film the essence of the consciousness I saw displayed. Perhaps, I was looking for something that refuses to be photographed. I was only chasing shadows, perhaps.

Text by Santu Mofokeng, 1997

Santu Mofokeng, Shadow Hunter is on view now at the Jeu de Paume in Paris - The exhibition and the accompanying book bring together a unique selection of the photographic essays made by Santu Mofokeng over the last thirty years. Well-known from his projects Black Photo Album/Look at me: 1890-1900s, Township Billboards: Beauty, sex and cell phones, Trauma Landscapes and Chasing Shadows, the South African artist took the opportunity of the invitation for this show and the production of his first comprehensive monograph, to delve deep into his artistic archive. "Santu Mofokeng, Chasing Shadows – 30 years of photographic essays" presents a selection of more than 200 images (photographs and a slideshow), texts and documents. The photographic essays he composed over the years, some of which are a life-long work in progress, range from the Soweto of his youth, from his investigations of life on the farms, the everyday life of the township and in particular, representations of the self and family histories of black South Africans, to images from the artist’s ongoing exploration of religious rituals and of typologies of landscapes, including his most current project Radiant Landscapes, commissioned specially for this retrospective.