Zhodi, San Francisco, California 1991. From Raised By Wolves. All images © Jim Goldberg. Courtesy of the artist, Pace/MacGill Gallery, NY, and Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, SF.

The Last Son: An Interview of Jim Goldberg

BY OLIVER MAXWELL KUPPER

PORTRAIT BY ARTURO OLIVA PEDROZA

Jim Goldberg exists in the canon of some of the greatest documentary photographers. Like Walker Evans or Robert Frank before him, Goldberg captures the pangs and fallacies of the American Dream with feverish curiosity, drive and ambition. His images are a thickly gauged needle slowly piercing the surface of our embedded societal perceptions. His first monograph, Rich & Poor, replete with handwritten notes from its subjects, is perhaps the most honest and heartbreaking photographic portrait of American life from opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum. The agony and the ecstasy of both the obscenely wealthy and the supremely poor, stand in stark contrast in society, but in Goldberg’s book they are given a rare democratic voice. As a Magnum photographer, he has traveled the world, but it’s the images that he shoots at home in his native US that are the most consciousness-searing. His project, Raised By Wolves, which was realized in the form of an exhibition that saw its debut at LACMA in 1997, and a monograph, captured the 10-year recorded documentation of teenage runaways: their interpersonal relationships, their clashes with police and social agencies and their ultimate struggle to survive. In his monograph, Open See, Goldberg explored the turmoil of refugees from over 18 countries, from Russia to the Middle East, Asia and Africa, cataloging a collection of humanizing stories. One of his latest projects, The Last Son, published by Super Labo, is his most personal and autobiographic work to date. Combining photographs, collage, handwritten text, and stills from home movies, the monograph forms a conceptual Bildungsroman and a portrait of a young artist coming to grips with his artistic pursuits.

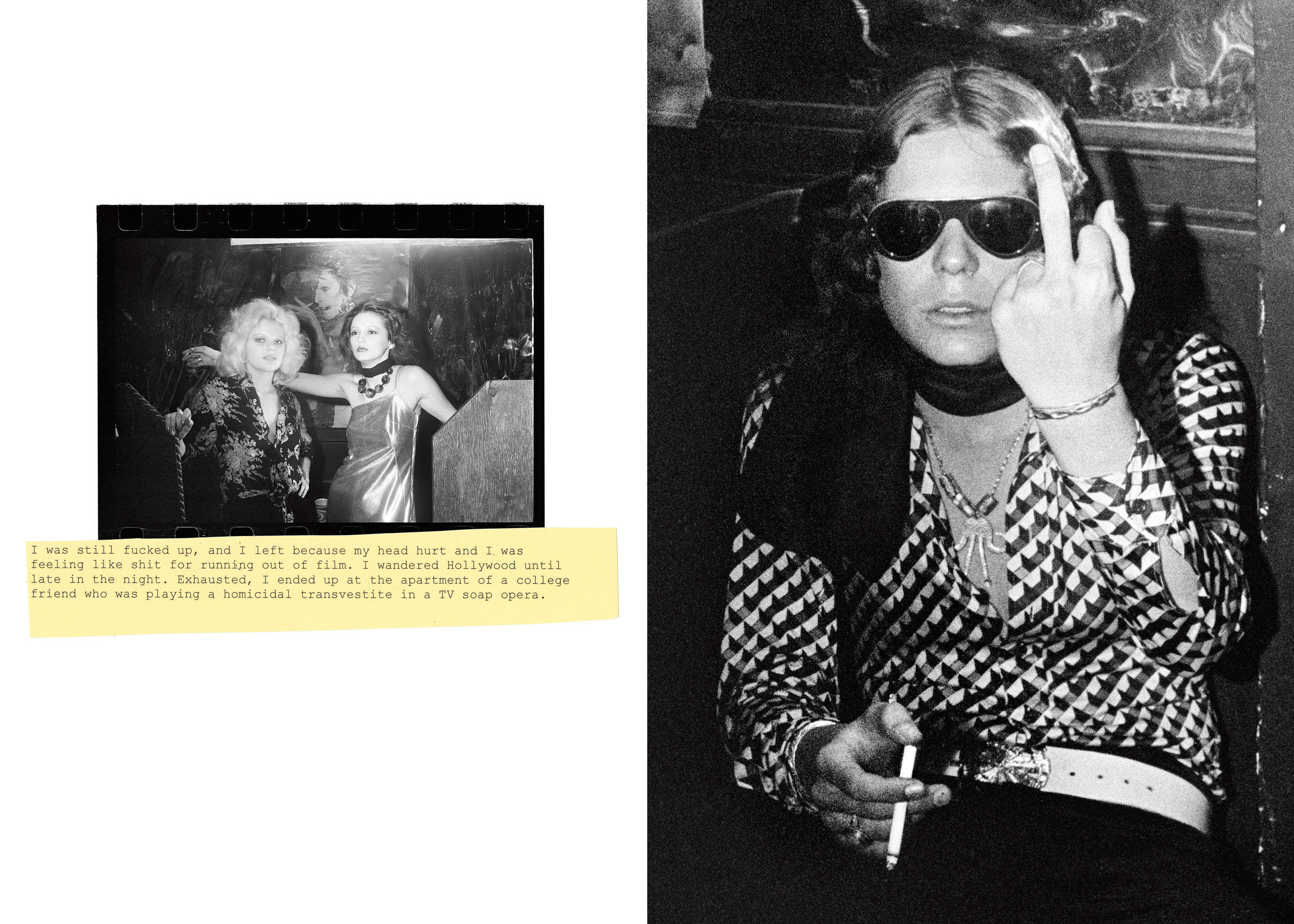

Spread from The Last Son, 2016. All images © Jim Goldberg. Courtesy of the artist, Pace/MacGill Gallery, NY, and Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, SF.

I’m Dave, Hollywood, California. 1988-1989. From Raised By Wolves. All images © Jim Goldberg. Courtesy of the artist, Pace/MacGill Gallery, NY, and Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, SF.

OLIVER MAXWELL KUPPER: So, what initially brought you to the world of runaway kids?

JIM GOLDBERG: I was looking for a way out of my hometown of New Haven, Connecticut. I didn’t quite fit in there, so I left as soon as I could. I eventually ended up in San Francisco where I began Rich and Poor. After it was published, I applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship for a project about kids who were considered “bad,” “troubled,” “lost,” etc., by societal standards. Since I had been deemed a ‘loser’ in my family, it all felt very relatable to me. When I received the Fellowship in 1985, I began what became a 10-year venture into a project about runaways – Raised By Wolves.

KUPPER: It seems like a lot of these kids created a myth about how they ended up on the streets.

GOLDBERG: Yeah. There were so many stories, one never knew what was true. Though most kids did have real reasons to escape from their homes like physical, emotional, and sexual abuse or being queer. For others, it was not fitting in or not wanting to follow rules. They often enhanced their stories by embellishing their backgrounds to sound tougher than the next and to gain ‘street cred.’ They were from all kinds of backgrounds, class and ethnicities. Dave’s story positioned him as being from drug-dealing-junkie-whore parents, but that was not true. In fact, his parents turned out to be devout Christians.

KUPPER: So what made you want to runaway? To get out of New Haven?

GOLDBERG: My parents were going through their own hard time and since my brother and sister had already left home, I was alone with that. I was like many teenagers who didn’t feel like they were understood. New Haven was a mess with race riots and white flight, and I hated the school I was forced to go to. I just wanted out. The kids in Raised By Wolves became reflections of where I came from. That’s the crux of it.

KUPPER: And it was sort of an era where there was a lot less supervision (the 1980's).

GOLDBERG: I don’t know if it was that or if suddenly we were acknowledging that so many children had slipped through the cracks and were winding up homeless. Many street kids were going down a path that does not usually lead to happy endings.

KUPPER: Your father was in the candy business, right?

GOLDBERG: Yes, he was a wholesale candy distributor.

KUPPER: Was there ever a pressure to join the family business?

GOLDBERG: My brother, sister and I were never encouraged to enter the business because it was, like my father’s health, failing. My father is a Willy Loman type character – a man who was never quite able to be who he wanted to be, and knew he never could be. The Last Son touches upon this and Candy goes deeper into that narrative.

KUPPER: In The Last Son, I read that you were trying to get into Rodney Bingenheimer's English Disco in Los Angeles. What was it about that place?

GOLDBERG: I went to LA in 1974 to live for a month or two and took the Green Tortoise bus down from Bellingham, Washington. Joints constantly passed around, I remember being quite uncomfortable trying to sit and sleep on top of each other. Out of boredom or fatigue, I picked up a faded Rolling Stone and read about Rodney and his Disco. I was fascinated. I don’t know what it was, or why, but I decided that this was the place I wanted to go to. Coming from hippie Bellingham, glamour boys and girls seemed like the perfect antithesis to me.

KUPPER: I had the same response to this place’s existence decades later, because it was sort of the West Coast CBGBs in a way.

GOLDBERG: Yes, exactly.

KUPPER: Your time in LA seemed really interesting, because you mention going to Bel Air Camera, which is exactly where I bought my first camera, and you hitchhiked around Los Angeles, which I’ve done a few times, but much later.

GOLDBERG: Yeah I had no means of transportation, so I either walked or hitched my way through town.

KUPPER: And there’s a story where you accidentally smoked angel dust with somebody who picked you up?

GOLDBERG: That story is towards the end of The Last Son. I finally received permission to photograph in Rodney’s for one night and had hitched a ride to Bel Air Camera for a flash. The guy who picked me up brought me to his home and offered me pot, which turned out to be angel dust. It was a precarious situation.

KUPPER: It sounds terrifying.

GOLDBERG: It was definitely sketchy, but pretty funny in retrospect.

“Though most kids did have real reasons to escape from their homes like physical, emotional, and sexual abuse or being queer. For others, it was not fitting in or not wanting to follow rules.”

KUPPER: You’re able to tell a story about your life in a really interesting way; you’re not writing your memoirs, it’s sort of an ephemeral documentation of geography, place, and your own personal life.

GOLDBERG: Yes, thank you for seeing that. While The Last Son is a coming-of-age story about the rise of my career and the fall of my father’s, Candy compares my experience in New Haven to the lives of two other men who grew up there during the same time. Candy plays with a spiral narrative structure–stories that repeat, reflect upon, and echo each other, inside a bigger spiral that is the life of the city itself. The real story is about betrayal–certainly in each of our personal lives but also in the “promised land,” that New Haven was supposed to be. The city eventually became such an isolated, economically divided, and racially tense environment–nothing like what was assured to its inhabitants.I thought it was important to take on the idea of promise and betrayal, but also how good intentions can go so drastically wrong. That’s more evident now after the election of Trump–how things can turn very badly very unexpectedly.

KUPPER: And quickly. Yeah and I think that American cities sort of become representations and metaphors for the American Dream in a way.

GOLDBERG: Absolutely. In the late 50s and 60s when there was so much wealth and hope. New Haven represented the Model City for a new post-war America. The reality was that things were a mess and were falling apart.

KUPPER: It’s pretty symbolic of your work, there’s sort of this hope and failure dichotomy that runs pretty deep.

GOLDBERG: Well, I don’t know if it’s exclusively hope and failure. It’s also about redemption, disparity, and dreams.

KUPPER: I want to get to that in a second, but growing up were you aware of the Magnum photographers? Were you inspired by post-war documentary photography? How were you introduced into that work?

GOLDBERG: I am basically a self-taught photographer. I did take a summer workshop in 1973, which turned out to be pretty formative. Nan Goldin and I were there together.

KUPPER: Was that in Boston?

GOLDBERG: Yes, in Cambridge to be exact. I went there not knowing much about photography, and didn’t know much about Magnum then. My first big influence was Robert Frank.

KUPPER: Well The Americans, that book is pretty legendary. The introduction by Kerouac. That book really captured America then.

GOLDBERG: Yeah,The Americans and The Lines of My Hand touched me in ways I had never felt. There was something about the way he showed the world that gave me the confidence to reach inside and discover what I wanted to do.

KUPPER: It was sort of revolutionary. I mean not a lot of people, besides Allen Ginsberg, were incorporating text and collage and all those things.

GOLDBERG: Since the beginning, I have enjoyed utilizing a variety of methods and mediums in my practice. In this case, I think the Super 8 footage, collage, handwritten text, and other alternative storytelling techniques have helped to suspend stories in time. Robert Frank did send me a letter once and it said something like, “Allen Ginsberg says thank you for your images and words because they help him understand how to tell his story.” Unfortunately, most of my letters and correspondence from that time are lost. My landlord threw them away.

KUPPER: Really? That’s awful. But it seems like maybe Ginsberg was inspired by the way you were incorporating text, which is interesting. You mention Nan Goldin and these current photographers that are documenting these different sides of life that a lot of people weren’t capturing before. Did you ever talk to Nan Goldin about photography or any of the other photographers that were sort of around at the time?

GOLDBERG: When Nan and I hang out we talk about the usual: our lives, where we were and where we are now. We are old friends now!

KUPPER: Where did your desire to document, to capture life, come from?

GOLDBERG: Hmm, I’m not sure if I’ve ever been asked that question. When Joel Sternfeld interviewed me about The Last Son in 2016, he said I was like a baby pigeon. I asked, “What do you mean a baby pigeon?” He said, “Well, you know, have you ever seen a baby pigeon before? No, because pigeons come out into the world fully formed. That’s how I see you, as someone who was fully formed by the time they got into photography.” I’ve seemingly always followed my instincts and intuition, and have been most comfortable going outside and documenting the world I saw along with people I met. I developed my practice around experimenting with the documentary form to avoid developing a constraining style. It’s a part of my practice I continue to work on and grow within.

KUPPER: You have photographed people from all over the world.

GOLDBERG: Yes, I’ve been very lucky. That’s one of the reasons I joined Magnum, to disseminate my work outside of the gallery and museum walls.

KUPPER: Like the Congo, I mean those are very intense photographs. Was that an assignment?

GOLDBERG: My book Open See came out of my first commission within Magnum in 2003. I was one of eight photographers who were assigned to document different aspects of Greek culture before the 2004 Athens Olympics. My focus was to be on immigrants in Greece. After my first trip there, I realized the subject matter was far more complicated than I had thought, and it was going to take more time, which is why I began Open See. Open See tells the stories of refugees, immigrants and trafficked individuals, and the kind of drastic struggle they go through when leaving conditions where war and economic devastation are prevalent. It also addresses their journeys from their countries of origin to their new homes in Europe, and the difficulties in adapting to a different culture, as well as the minimal efforts by that culture to adapt to them. I began the project in 2003 and ended it in 2009–way before issues about migration were on the radar in the U.S. But even then I could see that this issue was just going to become larger and larger.

KUPPER: When you are on the front lines you see it coming along the horizon.

GOLDBERG: I don’t think of myself as a journalist being on the front lines. But I certainly have been in places that are pretty relevant to what’s going on in the world today.

KUPPER: Any close calls? Any times where you felt like maybe I should get out of here?

GOLDBERG: Well I think I’ve had more close calls on my farm, where I’m always hitting my head on a tree branch, or falling off of a ladder! But, sure, I’ve had close calls in all of my work as there are always moments of difficulty and perhaps danger that need negotiating out of.

KUPPER: There’s that very intense photograph of the loaded gun being pointed out of a window.

GOLDBERG: Right, that’s from Raised by Wolves. It was a Russian roulette game Tank was playing – play shooting at people out the window in his hotel room. He declared that there were no bullets in the gun but then he pointed it at the ceiling: and bang.

KUPPER: Photographing through your explorations of the American Dream, a lot of people are feeling pretty pessimistic about what’s going on, do you feel like it’s this relentless nightmare or do you still have hope?

GOLDBERG: It depends on the day and the headlines. Given the mess we are in today–the roadblocks being thrown up at us on a daily basis, the dangerous thinking taking hold, the rudeness and lack of generosity–it is a bit difficult to think that things will get better. But I am a hopeful person… I resist in ways I can and keep myself busy by making work.

KUPPER: Your work seems quite hopeful. Looking at your works and photographs, there’s some dark subject matter but there’s playfulness and lightness to it too.

GOLDBERG: Sure, I feel that I’m always trying to keep it interesting, mix it up a bit, and occasionally use humor as a way to play with the story being told. Despite the harshness of the subject matter I never want to make work that is macabre, nor do I want to hit my audience over the head with a didactic documentary approach. Rather, I want to engage my audience with ideas and questions and not necessarily answers.

KUPPER: Can we talk a little bit about the text you incorporate in your photographs?

GOLDBERG: Sure. When I was in graduate school I began to develop a technique that involved people writing on photographs as another way of telling their story. This became something integral to my practice for 40+ years. At the time I developed it, I wasn’t thinking I’d have a show at MoMA or LACMA or make books, or that this was also the beginning of my friendship with the aforementioned Robert Frank. I saw something that I needed to try to make sense of and by adding text to photographs I felt like I was creating a more in-depth understanding of people and their situations. In turn, they became participants in the telling of their stories, which creates a closer connection with the viewer.

KUPPER: People didn’t really understand it and started to criticize it when Rich and Poor came out.

GOLDBERG: Yes, I got a lot of shit for defacing photographs with words.

KUPPER: What about today? How has your practice changed over the years? What are you working on now?

GOLDBERG: Well I’m still using some old tricks, and new ones too. I’ve been using Super 8 a lot, and hand-coloring large newsprint pieces. I also started documenting cities from on top of an RV, trying to make street views to counter Google Street Views. I just now started working on a sculpture that involves plastic bags, and experimenting with different three-dimensional materials and mediums…. Of course I’m a bit scared of where it’s all “going,” but I’m following my intuition… As always, it takes a little bit of faith to jump into the water.

El Chuco & Manny Garcia San Francisco, California. 1982. From Rich and Poor. All images © Jim Goldberg. Courtesy of the artist, Pace/MacGill Gallery, NY, and Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, SF.