Koak: Physiological Impetus and the sameness of visual language

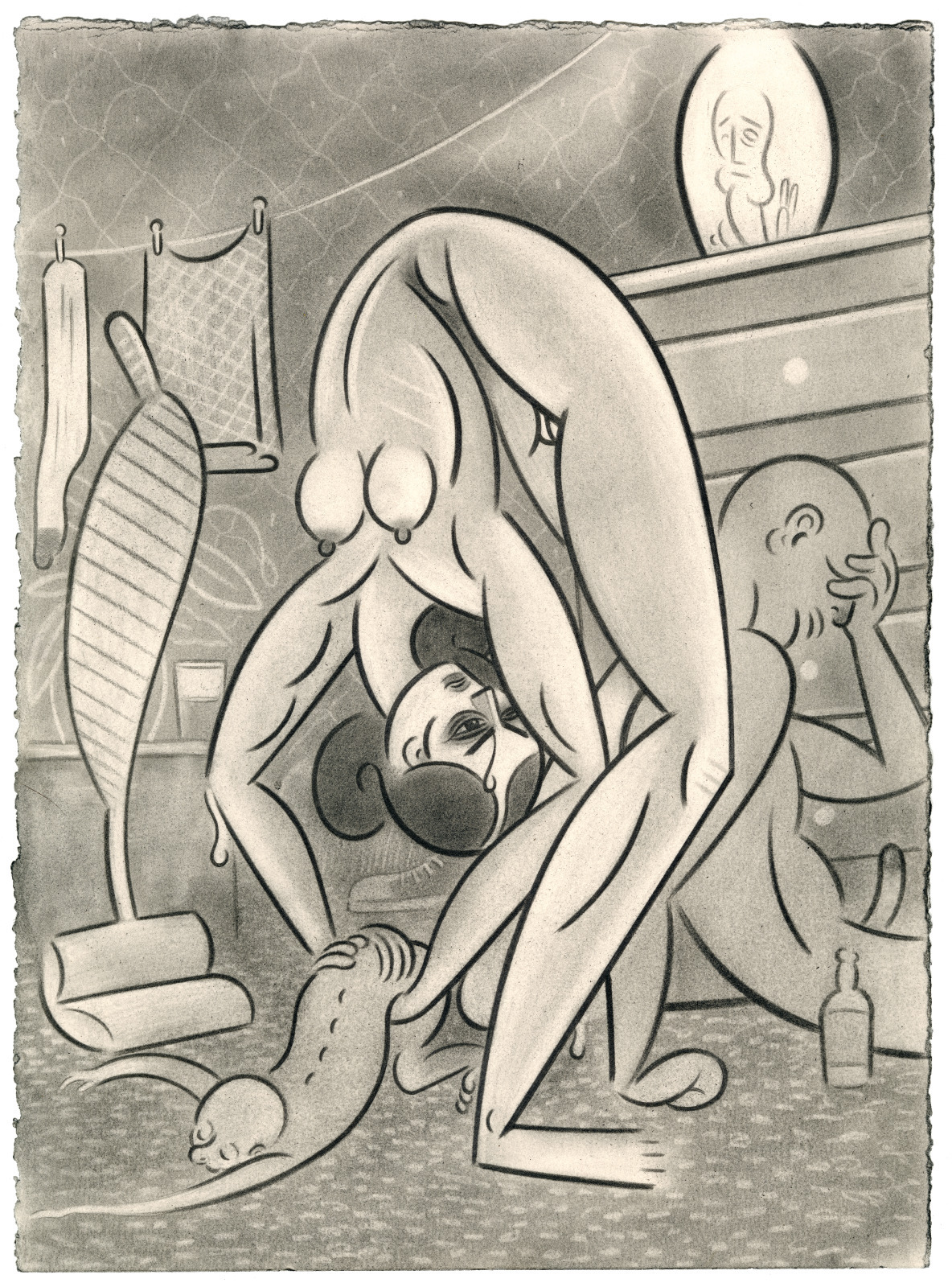

Heavy Handed, 2017. Graphite and casein on powder blue rag paper, 15x 11 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Walden Gallery

Interview by Summer Bowie

I first discovered Koak’s work two years ago when her San Francisco gallery, Alter Space, hosted a popup exhibition in Los Angeles called The Weeping Line. Her figurative paintings are dark, deeply layered, and convey sexual undertones that seem both private and unapologetic. Her lines are fluid, clean and precise. Her use of color is arresting in its mastery - at times pale and lean, at others monochromatic. Although, most of the time her work brandishes a full palette of vivid complementary pigments, rich in contrast with a delicate texture that feels exacting even in its most naive details. Since then, I’ve seen her work almost everywhere I go, in alternative gallery spaces like BBQLA and MAW New York, art fairs such as ALAC, Untitled, NADA and Material, and recently she has presented her work abroad in London, Sydney, and Buenos Aires, which is where she was when we sat down for a video chat. She had just returned from a long day of installing to discuss her early life and the ongoing health concerns that fostered her highly-focused practice, the under-appreciated power of comic books, and the new media she’s exploring as her work evolves into the third dimension.

Jenny-Goat, 2017. Pastel, pigment, chalk, and casein on rag paper mounted to panel 60 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Walden Gallery

Alice, 2018. Graphite, charcoal, watercolor, chalk, pastel, and casein on natural rag paper with dyed fawn inlay, 15 x 11.25 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Walden Gallery

SUMMER BOWIE: Your first and only name, Koak, where does that name come from and how does one end up with only one name?

KOAK: It’s been my nickname since I was a kid, when I was making art and showing it in coffee shops in Santa Cruz. I’ve used that as sort of a pseudonym for a long time. I started doing shows and a lot of them were really personal and I also worked with kids as well, so that separation was important.

BOWIE: Does it have meaning?

KOAK: It’s my initials.

BOWIE: You’ve mentioned that your childhood sickness fostered your entrance into art making. Is your personal health still a motivating factor for your work or practice today?

KOAK: Yes and no. For most of my childhood [my Mom] was in bed with chronic fatigue. My aunt and grandmother both have a lot of family health problems. When I was younger I had Kawasaki’s Disease, which is where your tongue swells up and looks like a strawberry and it affects the vessels going into your heart. When I was in my early 20s, I had PID, where your uterine tubes fill up with pus and dry out and it can leave you barren. I think it’s made me more aware of my body than normal, healthy people have to be. A lot of the work is about the body so it feeds into that— I’m very aware of bodily sensations or what it feels like to be stuck in your skin.

BOWIE: I read that you had a teacher who showed you photos of alien autopsies, what was that all about?

KOAK: I went to Santa Cruz High School and my high school art teacher was definitely a force— if you were feeling lost in life, she was good at giving you inspiration. But she believes in Sasquatch wholeheartedly, and she would play a lot of alien autopsy videos. There was a utility closet across the classroom, and she gave me and my best friend a key and let us use it as [our] private studio. We put a coffee maker in it and drew comic books. It was our safe haven that the rest of the school couldn’t get to.

BOWIE: How did you get introduced to comic books and what were your favorites growing up?

KOAK: I think my first boyfriend had a big collection of them. We broke up when he went to jail, because he had a bit of a heroin addiction, and I think he felt bad and gave me his comic book collection. I really loved X-Men at the time, I really was a big fan of the Marvel books and I had a really big crush on Storm.

BOWIE: I remember being obsessed with Mystique and having binders of the collector’s cards as a kid. As somebody who’s part of the Bay Area artistic community, what does the scene look like from the inside?

KOAK: I get asked that question a lot. I think maybe because it seems like we have lost a lot of really great artists who haven’t been able to stay there or afford spaces. To me it seems like it’s a really strong community. We know a lot of people that are creative and put a lot of energy into showing up for each other. I have a lot of friends in New York and LA but I think I would have a really difficult time living in a city that has such a big art community, because I would feel obligated to people and then I wouldn’t get my own time. In San Francisco you can show up for your friends but you don’t feel like you’re constantly worn thin.

BOWIE: I want to talk about your approach with figurative art. For the past couple of decades, I feel like conceptual art has just dominated the global art scene. Lately, figurative painting is having a resurgence that seems to have come out of nowhere. Do you have any theories or thoughts on why that might be?

KOAK: I have no idea— I know why I love to see it. When I was younger and making art, a lot of it was about this idea of feeling human again. To me, that’s something that people are really craving— reclaiming the idea of being a human. I remember making stuff that was about how everybody felt very cut off from their emotions. We’ve been doing that for so long— suppressing that part of ourselves. A lot of [my work] is kind of cartoonish or semi-comic inspired figurative work, which is really nice to see because comics have been really dragged through the mud and not appreciated in art history or museums.

BOWIE: It’s fascinating where you’re coming from, because you received an MFA in comics. You’re a figurative painter in many ways, but you can see all the references. Is this what you intended to be doing when you were pursuing your degree?

KOAK: It’s funny, my comic book work is actually a lot more technical than the fine art work I do. I would say that my comic book art looks more like old etchings and my fine art looks more cartoonish. They’re kind of flipped. In the last year of my MFA program I injured my hand and I started doing figurative work like the drawings and paintings I’m doing now, which is more like the work I did prior to starting the comic book. To me, they use the same language. Both comics and visual art are the same; it’s really stupid that we give comic books a bad name.

BOWIE: But your work in particular is very symbolic and allegorical, especially with works like Jenny Goat. Can you talk about that piece and its symbolism?

KOAK: I started that as a drawing. It was loosely based off my friend Jenny. Every time I’d visit her at her house, she had a goatskin on the back of her couch. She used to live on a farm where they raised their own animals and they would raise and kill and use all the parts of the goat. The goat’s name was also Jenny. It seemed odd that she had a goatskin from a goat named Jenny and her name was Jenny. I used to be vegetarian and I have a lot of friends who are vegan, and I really respect that choice. I wish I had the strength to raise and kill my own animals if I could. I can’t imagine doing that. That piece made a lot of people very distressed about the symbolic goat getting killed. I started it as a sketch and there was a copy of a burning book… that Ayn Rand book… Atlas Shrugged. When I was working on the piece this business guy comes up and he was really drunk and he’s like, “this reminds me of a quote” and then he quoted that book. It was something about how the strong survive off the weaker. The piece for me turned into this conundrum of… in that process of killing things that are weaker than yourself, you’re doing yourself a disservice in a way. The woman is killing the goat that has her own name and they’re both crying.

BOWIE: I think that we do lose a little bit of ourselves in those experiences and an ignorant person might momentarily feel empowered by that, but it’s fleeting. They mistakenly assume that being insensitive protects them from feeling, but they’re feeling all of it. It’s just all so deep in there that they don’t know what to make of that storm going inside.

KOAK: To me, that’s why we have a lot of health problems as well. You just shove it down and it comes out other places. You get a rash, or worse, you die of a heart attack when you’re old.

BOWIE: Have you explored other mediums outside of drawing and painting?

KOAK: Prior to the work I’m doing now, I did a lot of installation work. I just did my first ceramic piece last year and my first bronze pieces at the end of last year. When I get home from Buenos Aires I have two weeks to do a bunch of sculptures for a show with Ghebaly. That’s something I’ve been doing and really enjoying.

BOWIE: Does it feel any different translating those ideas into three dimensions?

KOAK: I think that any visual language feels the same, you just use your hands in different ways. I’ve always been interested in using very different mediums. I’ve done work in VR or with electronics, or with bookmaking and print making, and three-dimensional stuff as well. For sculpture, it feels like drawing. You’re still creating lines and you’re still making a shape that leads the eye different places. The only difference is that you have to make sure you’re looking at it at every angle so that you don’t turn it one way and it looks like shit from the other side.

BOWIE: What do you do when you’re not making art? Are you ever?

KOAK: I don’t get a lot of chances… It’s been kind of nonstop for the last couple of years. I’m trying to find more down time. I cook a lot because I have allergies to things. I hang out with my cat. We have a nice, boring life.

Hard Times Need Comfort, 2018. Acrylic, oil, graphite, pencil, and casein on stretched muslin 15 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist and BBQLA

Infinite Loop, 2017. Graphite, charcoal, watercolor, chalk, pastel, and casein on natural rag paper with dyed fawn inlay, 15 x 11.25 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Walden Gallery