the Killer inside you

Interview by Oliver Maxwell Kupper

Photographs by Eddie Chacon

Styling by Sissy Sainte-Marie

Hair and Makeup by Maria Migliaccio

Diary Photos Courtesy of Matthew Modine’s Full Metal Jacket Diary,

Restored and Curated by Adam Rackoff

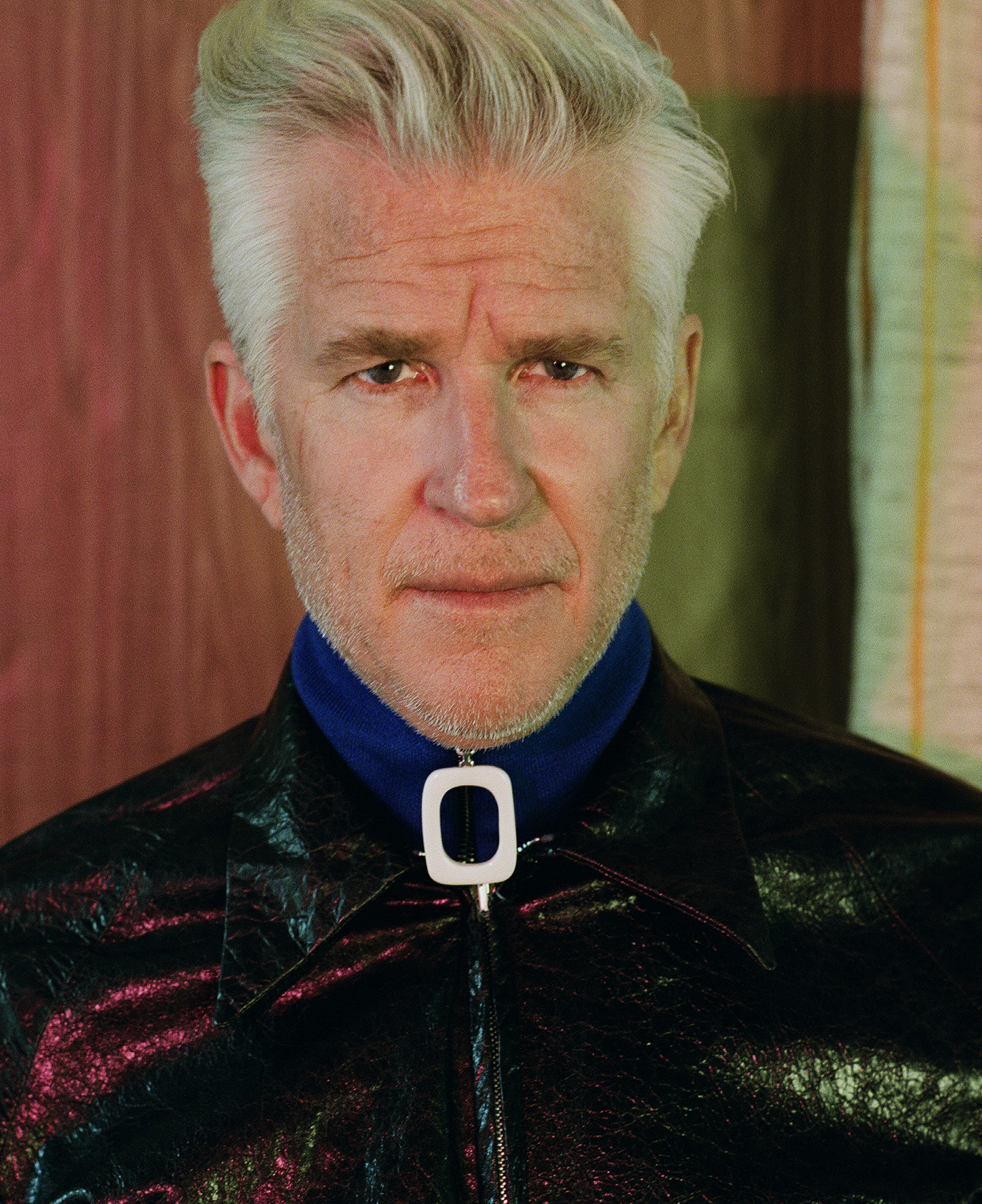

Neckband by JW Anderson

Leather jacket by Westley Austin

I first met MATTHEW MODINE in the summer of 2017 – a year that marked the thirtieth anniversary of Full Metal Jacket. We discussed the diary he kept while filming Stanley Kubrick’s iconic, psychologically searing war epic. The images Modine captured on set in England — a foggy and far cry from Saigon — were all shot on a Rolleiflex camera that the young actor hid in his flak jacket to avoid the ire of Kubrick, a notoriously despotic, and exacting filmmaker with zero patience for im- perfection. The journal entries describe life on and off set, the agony and the ecstasy of working with Kubrick, the come- down, and life after crouching in the make believe trenches. The first thing I noticed about Modine was his shock of white hair – a remnant from his role as the sinister Doctor Martin Brenner in the Netflix series, Stranger Things. But Modine is anything but sinister. Yet, with the right lighting, the right stagecraft, the right direction, the right words, Modine can become anything: an evil doctor, a wisecracking journalist, a mute casualty of post traumatic stress disorder who is convinced he is a bird, anything. His roles are believable because he is a confident, gifted, and trained actor with a natural comicality, deep pathos and vulnerability. Off screen, he is smart, worldly, and curious. We met again this spring for the following interview.

OLIVER KUPPER: I want to talk about your father who owned a number of drive-in theaters – you mentioned in the diaries seeing John Wayne films and Sam Peckinpah films. Was that your first introduction to filmmaking?

MATTHEW MODINE: The drive-in had a tremendous impact on my juvenile years. I think in the same way that video stores had an impact on Quentin Tarantino. When you’re exposed to so many films it becomes a kind of language. In my case, because we’d play the same movie for weeks, I could see a movie three or four times in a week.

KUPPER: You were really studying actors on screen and studying the way films were made.

MODINE: Yeah. One of those people was Sean Connery. I’d of course seen Sean Connery in the James Bond movies. And then I saw him in The Man Who Would Be King and thought, “Wow! that’s the same guy as James Bond.” And then I saw him in a very early movie where he was singing, called called Darby O’Gill and the Little People. That’s when I became conscious of what acting is.

KUPPER: How old were you when you realized that acting was going to be your path?

MODINE: I had an uncle and an aunt that lived in Beverly Hills and we were living in Utah at the time. I started lying to my friends and telling them I was an actor. So I would spend summers with them. It made it easy for people to believe that I had some closer connection to the movie biz because of the drive-in. I told my aunt that I had this ambition and she bought me a book by Constantin Stanislavski, called An Actor Prepares, and the book was way over my head. I had no idea… just the person’s name: Constantin Stanislavski. The whole thing was alien to me.

KUPPER: When did you finally move to New York City?

MODINE: I thought if I go to Los Angeles I’ll just be another surfer blonde kid that wants to be an actor, but if I go to New York city, there’s some great mystery there that’s held for me. Everybody that I ever met from the east coast, they seem to be smarter and conscious of life. So I made that journey to New York City. Then I end up working with Stella Adler, who was a student of Stanislavski, and it was in her school that I learned all the mystery of that book. From the time of lying about being an actor, 10 or 11 years old, to moving to New York City in less than 10 years. Visualization….there’s something to that. It brought me to Stella Adler where I became a student.

KUPPER: One of her most famous quotes was “Find the killer inside you.” Being such an inherent pacifist, was it difficult to find the killer inside you?

MODINE: No. It’s very interesting today as opposed to when I was in acting school. Today we understand what DNA is, DNA is coded and we understand now that we’re all brothers and sisters. We all come from the same place, which is beautiful and should make a more peaceful world. How can we fight with our brothers and sisters? It should make us keep the world a more loving place. But within that DNA exists ambitions of our ancestors. It may be within my DNA that I’m fulfilling the ambition of someone that came before me. Within that DNA, somewhere along the line, I’m sure that there was somebody in my bloodline that was a killer. You don’t have to look outside to find it, to play a killer, you can look within and find that killer that exists within you.

KUPPER: I want talk about Full Metal Jacket. You mentioned in your diary that Val Kilmer was the first person to tell you about the movie.

MODINE: I was with my best friend David Alan Grier. We were laughing because we were sitting in this restaurant where Woody Allen in the movie Annie Hall tried to put this big Cadillac in reverse and drove through a wall. There was an actor at another table looking at me and saying, “Fuck you,” and giving me a really dirty look. I said “David, this guy’s got Tourette’s or is rehearsing a role.” David looks over and says, “That’s Val Kilmer, he’s a really nice guy.” David went up and talked to him and waved me over. I said, “How are you doing? My name’s Matthew,” and he said, “Yeah I know who you are I’m sick of you.” I said, “Look if you have a problem with me let’s take it outside.” Val was sick of me because I was getting all the roles. You know, Vision Quest, Mrs. Soffel, and Birdy. Then he tells me that I was cast in Full Metal Jacket. I said, You don’t have to worry about me doing Full Metal Jacket, I don’t know anything about it.”

KUPPER: How did Val know about it?

Hat by Off-White

Jacket and T-shirt by Westley Austin

Pants by COS

Shoes by Brandblack available at Assembly New York

MODINE: I ran outside after we finished breakfast and put a bunch of quarters into the payphone and called my manager and said, “Chuck, do you know anything about this Kubrick movie?” and he said, “No, nobody’s contacted me.” I asked Harold Becker if he would send Vision Quest to Stanley Kubrick, and Allen Parker, who was editing Birdy, if he would send over some scenes. Then I got a script in the mail from Stanley Kubrick saying, “Hello my name is Stanley Kubrick, I’m a film director and I’m wondering if you’d be interested in working on my project,” and that was it. He didn’t say what role it was. The script didn’t look like anything I’d ever seen before, it was not formatted like a script. It was more like an outline for a book. Suggestions of things that might happen, suggestions of things that people might say. I didn’t even know what role I’d play.

KUPPER: What role did you want to play?

MODINE: I thought that he saw Birdy and imagined that I’d be good for the Pyle part, which was a great part. As I kept reading, I wondered if he’s interested in me playing Private Joker. Private Joker died in the original script. This was the role that I had been looking for, because after Birdy, I wanted to go to work on something equally as powerful. That’s when Top Gun was offered to me, when Back to the Future was offered to me. But I just was looking for something that didn’t feel like those brat pack movies. I was looking for something much cooler, either working with Frances Coppola on something like Rumble Fish, something strong and powerful.

KUPPER: Meeting Kubrick for the first time in London, what was your first impression of him?

MODINE: Everybody started telling me stories of Stanley Kubrick, how he’s this and he’s that, he’s paranoid, he wore a football helmet when he drove his car, he had airplanes fly over his house and spray the mosquitos because he was paranoid of malaria or AIDS, all these crazy stories. So his driver, Emilio, drove me into London and picked my wife up and took us out to his house for dinner to meet. We came into this amazing estate, it was like a gentleman’s farm, a working farm, but don’t think American farm…

Hat and shirt by COS

KUPPER: The English Countryside.

MODINE: Yeah. We drive up to the house and this guy wearing an army jacket and a beard and a bunch of dogs jumped out and they’re barking, jumping on the car, and he very shyly says, “Hi, my name is Stanley.” He was the most unassuming, jolly man. Certainly not like any other film director that I’d ever met. We had dinner and his genius, his brilliance, his intellect I should say, was apparent. His observation was amazing and his specificity in conversation was all a little bit like a chess game. He was a great mentor and a great teacher to me. He taught me how to write, he taught me how to improvise, not in a scene or dialogue, but on a film set. That you have to be open to improvisation.

KUPPER: You mentioned in the diary going out and shooting watermelons with a tommy gun. Do you think Stanley was preparing you for the role or was this one of his chess moves?

Neckband by JW Anderson

Leather jacket by Westley Austin

MODINE: I don’t think he was preparing me for the role. You know he grew up in New York City, in the Bronx, and having guns and shooting guns was not normal. His father was a doctor…the gun thing was kind of naughty. It was this crazy gun called a street sweeper. It was like a tommy gun but with 12 gauge shotgun shells. You wound it up like a clock and as you pulled the trigger, the next 12 gauge shell would go into place. You could shoot 12 rounds as fast as you could pull the trigger. It was really for killing people at short range. It was a short barrel so it would spray a lot of bullets and pellets out. At 30 or 40 feet the pellets would lose their velocity and their ability to kill, but at short range, 10 to 15 feet, this was an absolute murderous weapon. I think he thought that was kind of thrilling and exciting for a kid that grew up in the Bronx, having this weapon and being able to go out in the garden and destroy some pumpkins or watermelons. Just blast them. After I pulled the trigger and destroyed the watermelon, turning and looking at him, and he had this grin on his face

KUPPER: And in your diary there’s all these little moments like Kubrick making coffee or that scene of Kubrick getting really upset over the crushed rabbits. It really seems like you painted a completely different portrait of him. Recording those moments, were you consciously trying to record Kubrick as the man and not Kubrick as the legend?

Leather pants by Westley Austin

MODINE: No, I was too naive. I was too young. I was just making observations. That’s what I love about the diaries. It’s not me today writing about that experience, it’s about a young boy and his observations what was happening to him. Reminiscing and looking at it from a 50-year-old perspective, I think that for an artist to be a certain kind of artist, because there are different kinds of artists. To be the kind of story teller that he was, he had to be deeply connected to the natural world and to human emotion beyond the facade of the flesh. He saw within the person, beyond the skin.

KUPPER: You arrived on set with a camera. Did you ever speak to Kubrick about his days as a photojournalist?

MODINE: No. A good friend of mine, Joe Kelly, gave me the camera, a Roloflex, and told me that it would be a great tool for breaking the ice with Stanley. That if I had the camera and I knew how to use it, it would be a good conversation starter. I was nervous. I was going to meet Stanley Kubrick. I had the camera around my neck, trying to impress him with it, and then one day he looked at me and said, “What are you doing with that old piece-of-shit camera?” And I said, “Well, it’s a Roloflex…” and he cut me off saying, “I know what it is.” He told me to get this new Minolta auto focus, all the lenses I needed, he even told me what camera bag to buy. I didn’t like the Minolta, but I loved the Roloflex because of the way people behaved in front of it. It was a dyslexic camera and in that way it kind of made the world make sense. Upside down and backwards. I kept that camera with me, when we went to Vietnam and at boot camp, inside my flak jacket and when we were filming and I saw something interesting I would snap a picture. I had prints made and I gave them to the different actors I took pictures of. I gave pictures to Stanley. His criticisms about exposure and composition were invaluable.

KUPPER: Did you ever feel like this film was never going to be finished?

MODINE: Oh yeah. Towards the end. It really felt that way when I went to Italy to meet the Taviani Brothers who were giant film directors. They said they wanted to give me a role in the film, when do you finish? I said that the schedule said two weeks, or something, and they said, “Great, we’ll wait for you.’ I went back to London to finish the last two weeks and after a week they called me to ask how it was going and I said, “We still have two weeks.” They said, “Okay, we will wait another week.” Another week passes and they call me and I tell them we’re still in the same place, we have two weeks. They tell me they are sad, but they have to go with someone else. I told them I understood and I was sad to lose the Taviani movie. They finished their movie and we were still filming.

KUPPER: That’s wild.

MODINE: I got another movie. Alan Pakula came to London to ask me to be in a movie called Orphans with Albert Finney. I auditioned for that and he agreed to cast me, so he asked when I finished. It felt like I was going to lose that film as well. When I finished with Stanley, I went straight back to New York to work on Orphans. My hair was short because we just shot boot camp. We had two weeks of rehearsal on Orphans before we started shooting, because it was a play. I was new because Albert Finney had been doing the play for about a year and Kevin Anderson had been doing the play for a couple years, so I was the person who had to get up to speed.

KUPPER: So you were just thrust into the next segment of your career. What was your emotional state after it was completely wrapped?

MODINE: I didn’t realize how bad it was until after Orphans I was asked to do Married to the Mob with Michelle Pfeiffer and directed by Jonathan Demme. When I read it, the character, the part… It’s called Married to the Mob and I realized that it’s not going to keep me busy. What I don’t want to do is go back to work on a film like Full Metal Jacket where days and days would go by and not be working. I wanted something challenging and difficult and something that would require my time. I didn’t want to do Married to the Mob three or four times before my agent started yelling at me and demanded that I do the film. They made the part a little bit bigger. I’m glad I did it because it was really lovely working with Michelle Pfeiffer and Jonathan Demme is a really great director and Dean Stockwell is great and Alec Baldwin is only in it for a few minutes but he’s really memorable.

KUPPER: You are also a painter. How often do you paint and how would you describe the different mechanisms of painting versus acting?

MODINE: I don’t think it’s a coincidence that a lot of actors paint. Especially with film actors…It’s a way of doing something creative that’s also very selfish. When I started painting, my father taught me using water colors. My brother gave me acrylics for Christmas one time. I didn’t even know what the word meant and I didn’t have a canvas, my dad being a drive-in movie manager, seven kids, and not a lot of money, so I saved up for one thinking that these were some kind of special paint. I realized while using them that they are just water colors. And I loved the process of using them and then eventually getting to work with oils. It’s a whole different experience of creativity.

KUPPER: When did you start becoming an activist?

MODINE: Well it was before I moved to New York. I went for one year to junior college in Chula Vista. I was studying oceanography. I went to class and my professor was crying and I said “What happened? What’s wrong?” and he said “at any moment the ocean is going to die.” And he was speaking in geological time, but in that moment he was talking about acidification and chemical spills and oil spills. He said “you know what it’s like when you swim in a pool and your eyes get burned? Imagine what it’s like for all of the creatures in the ocean that aren’t able to escape the chemical spills and oil spills and the acidification.” He’d be suicidal today if he knew what was happening in the ocean and the speed at which it’s happening. But because there was that kind that wanted to be an actor, there was also a kid who wanted to be like Jacques Cousteau and sail around the world studying animals and traveling. That would be a cool life. He told me to drop out. That’s when I moved to New York. But I never lost that passion or that love for the ocean. My father taught me that when you see a problem, look at is an opportunity for a solution. Don’t just look at it as garbage all over the ground, bend over and pick it up.

KUPPER: Another part of the solution is to create programs that educate people.

MODINE: So with this program that I’m making called Ripple Effect, while I talk about the problems that the oceans faced, the whole backend and purpose of the show is to talk about opportunities for solution. Here’s something that you can do, here’s some people that you can contact. We use 500 million plastic straws a day in the United States.

KUPPER: And those are all ending up in the ocean.

MODINE: When you go to the bar and they make you a drink, tell them “please don’t put a stupid little stir straw in my drink.” When you fly on the airplane and you have a cup of tea, the stewardess puts a plastic straw in it. It’s just something you take out when they give it to you. But when you put plastic in hot beverages, it leeches the dioxide out of the plastic. You’re fucking poisoning yourself.

KUPPER: These days, what roles interest you? Do you feel a switch as you mature as an actor and do you have an interest in different roles?

MODINE: What I am interested in is challenges. That’s why I like working with you and the magazine. It’s like jumping out of an airplane. I read an interview and I feel like I get to know that person and I am thinking about how I want to shoot them with my Roloflex. Looking for an acting role, directing, whatever, I want to do something that’s really challenging. Challenging cinema is becoming more and more difficult to get made and they want you to do it for less and less money. There is only so much time left. You spend your life climbing this mountain and you reach the summit. You look down to see where you came from and simultaneously you see where you are going. The journey home is always shorter than leaving. Once you reach that summit and you see where you’re going, time accelerates. I know I have a designated amount of time and I want to accomplish something with meaning while I still have it.