The search for SOMA: julio mario santo domingo & his lsd library

Carl Williams in Conversation with Oliver Kupper

All images courtesy of Carl Williams and The LSD Library

AMERICAN NEWS REPEAT, Business Men Are Going To Pot, 1967

If the big bang created the Earth and solar system, the 1960s was the grand paroxysm of the counter-culture that resulted in a mushroom cloud of free love and mind expansion. LSD and psychedelic drug experimentation had profound socio-political and philosophical ramifications. As the generation waned and the high tide of ideological abandon rushed back to sea, the flotsam and jetsam remained ashore: posters, books, pamphlets, acid blotter sheets, photographs and other ephemera. One of the biggest collectors of this illuminated debris was Julio Mario Santo Domingo, a businessman who happened to be a member of one of the wealthiest families in Colombia. His LSD library – not named after the drug, but his dog, a Wheaten Terrier by the name of Louis Santo Domingo – owned one of the world’s largest compendiums of material related to altered states. His collection was also steeped in scientific research on cannabis, hashish, opium, coca, peyote, LSD, anaesthetics and the effects of heroin. Part of the collection is now in the hands of Harvard University. In this interview, we talk to rare books dealer, Carl Williams, who played a key role in sourcing and building the LSD library, and who has many of these items for sale in his catalogue.

OLIVER KUPPER: Why do you think the counter-culture of the ‘60s is popular again…is it the legalization of marijuana?

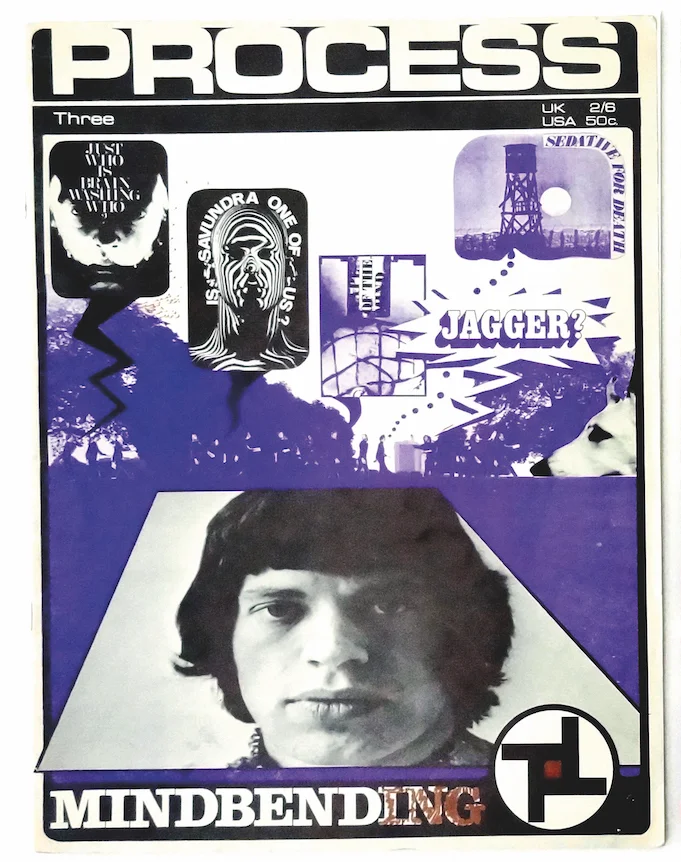

The Process Church of The Final Judgment Process Issue THREE “MINDBENDING,” 1967

CARL WILLIAMS: It’s totally the legalization. I’m getting a lot of click-throughs in British Columbia. The center of the dope universe. I was like, “Fucking hell.” So, in the past if it had been some North American railway barons and you were trying to sell to them, you would have to get through a whole courtly system. And here I am, a few hashtags, an email, and that’s it. Something’s happening innit?

KUPPER: It seems like the counter-culture is reabsorbing the collection, which is fascinating.

WILLIAMS: Oh, totally and utterly.

KUPPER: What initially brought you to the world of rare books?

WILLIAMS: I was working as a shelf stacker at the London School of Economics Library while I did a master’s degree program. I was one of those people who is clever but spent too long in school. I was in my twenties or early thirties, and I didn’t have any money and was sleeping wherever I could, but somebody sold me a very nice Yves Saint Laurent suit for 113 quid. One of the librarians at the library said, “Look, we’re moving locations briefly and we’ve got all these books and we need to move them and get rid of them.” And I started to take these books, in my Yves Saint Laurent suit and black t-shirt, to these posh book shops.

KUPPER: When were you introduced to the counter-culture stuff?

WILLIAMS: It had always been a part of my life. I was sort of an autodidact who stumbled into higher education. I’d never really seen a difference between the ideas that somebody might tell you while you were washing dishes in the kitchen or an official intellectual, so the counter-cultural thing was always there for me. I’d always been able to see high and low.

KUPPER: How did you get your hands on some of the first counter-culture material?

WILLIAMS: I started working for a bookshop called Maggs Brothers around 2003. My boss at the time said, “There’s this guy you have to meet, named Julio Santo Domingo. He’s been coming in for decades and his family is rich. His interest is mainly drugs.” So, I met him eventually and sold him a book I found in Coconut Grove. It was the only known document of the drug experience of an anti-muralist painter called José Luis Cuevas. His brother was a Doctor and in 1957 he injected him in the neck with LSD. There was an immediate reaction and he started to do a trip diary - a load of drawings and stuff. Julio bought the book a little too quickly.

KUPPER: What was Julio like as a person?

WILLIAMS: Capricious, kind, argumentative, passionate. Thoughtful. For instance, he knew romance-based languages: Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, French because he went there, he was a Francophile, and English. Any language that was related to romance languages, he could speak them with ease and read them with ease. Latin as well because he had a Catholic background, I guess. He was a truly open person.

KUPPER: He was intuitive and open. He almost seemed like a character out of a Mexican, or South-American novel or something.

WILLIAMS: Totally and utterly. He knew Gabriel Garcia Marquez very early on. He went to Cuba with Gabriel and had a seven-hour dinner with Castro. He not only came from the home of magical realism, not only was he saturated with Borgesian ideas of realities passed through Gabriela Garcia Marquez from the strangest country in the world. Breton said that Mexico was the most Surrealist country, well he was probably wrong, it was probably Columbia. Then he came to rock n’ roll through his grandfather…who introduced him to the Rolling Stones very early on. At twelve years old, he went to the studio where they were recording one night and smoking cannabis. That’s probably where his sense of an inner journey, or whatever they used to call it, came from.

KUPPER: So, you started off as a partial curator, helping him collect…

WILLIAMS: All of that’s crap. What I really was I was part of an exhibit, part of his collection. He shelved me.

KUPPER: He was collecting you.

WILLIAMS: I was a talking exhibit. I was like something from a very benign Star Trek episode. So, in my mind, the analogy, if you don’t mind me going on, is like when Timothy Leary had left Harvard and went down to Mexico, sort of in a pretend exile, and they went to a place called Zihuatanejo to set up this intentional community, an LSD- based seminar movement based on Tibetan mythography. Leary had built this observation tower on the beach because of the treacherous Sea of Cortez. He insisted that someone should be tripping at all times in that observation tower. And it was a bit like that with Julio and me – I was the guy tripping in the observation tower.

KUPPER: So, his LSD library, most people think it’s named after the drug, but it was actually named after his dog. He loved dogs.

WILLIAMS: He loved this one dog in particular. Louis Santo Domingo. He was a nasty piece of work. He did this thing when he’d first meet everybody. Julio would meet people like supermodels and shit and people like me, as well as Kings, Queens, Castro whatever and the dog would stick his nose right into your crotch, straight into your fucking scrotum or vagina and smell, and then he’d go away after he’d established dominance. I’d tell people who were selling to Julio, “Don’t stroke the dog.” I nearly accidently killed the dog once by trapping the leash between the elevator doors.

KUPPER: So, how many floors was his collection housed in?

WILLIAMS: It was two floors. But I want to convey just how big it was—it was fucking huge.

KUPPER: Was it a commercial center?

WILLIAMS: Yeah it was like a small business center. It was directly opposite a pencil factory. You could smell pencils every morning. You’re in this situation where you’re getting these Proustian evocations and of course he was a huge collector of Proust.

KUPPER: I want to talk about Julio’s family. I was reading an article from Forbes - I think it came out in 1992. His family were listed as the only legitimate billionaires amongst a bunch of cocaine empires, in Colombia at the time.

WILLIAMS: That’s right. It was interesting – when they employed me, we never talked about their wealth. Not because I was greedy or fascinated by money, but I was absolutely fascinated by somebody who might be a young Marxist and then you meet them and then they’re terribly nice. That thing you just said—you’re exactly right. But the family didn’t even get involved in public works, because public works in any country always end up involving corruption, because bribery was always involved.

KUPPER: It’s interesting. Going back to your beginning, it seems like you and Julio were both misfits, but you both had a conscience.

WILLIAMS: Totally. To me, it was about simplicity. I believe that Julio wanted not to give it away, but I believe he wanted to find a way to disseminate his wealth among all of these book dealers. He loved that world.

KUPPER: The whole crime thing seems pretty complicated. I was reading about how some of his employees were being abducted and killed during that time.

WILLIAMS: He never talked about that specifically. He did say something about how he was for his home country, that it was a place that you couldn’t really go back to. That’s the thing about all these rich Colombians in New York…they have this weird melancholy about them. That widespread violence that makes any crumb of decency absolutely impossible, and everything is tinged with the sadness of tens of thousands of people dying. Colombians grew up with that. Yes, Julio had lots of cocaine things, but they were sort of important to the contemporary history of Colombia.

KUPPER: I wanted to ask where you sourced some of those sheets of acid?

WILLIAMS: All of that stuff came from Julio. It was left over. It was under my desk, and Harvard came and took a majority of it. We only had five thousand boxes there, and of course I used to live there and work there. I knew that there was a box under my desk.

KUPPER: What were some of your favorite pieces in the archive?

WILLIAMS: Probably the PhD thesis for the Marsh Chapel experiment. It looks a bit mechanical now, but up until that time that’s the single most important investigation, psychological, sort of pseudo-scientific investigation into the nature of consciousness and mysticism.

KUPPER: When was that written, the ‘60s?

WILLIAMS: 1966-67, something like that.

KUPPER: It seems like the counter-culture of that decade was rife with that kind of thing, but also because there was a connection between psychology and the counter-culture.

WILLIAMS: The military industrial complex, all three. Like Kesey, they gave him these drugs, and they were government experiments, and one day they left the cabinets open. There was a jar of LSD and he took that, and that’s how he seeded whatever he was doing. Was it intentional? Was it part of a larger experiment? Was there an MK Super Ultra experiment that was running at the same time? And the same with Leary said… he was recruited by Murray to Harvard… an MK Ultra psychologist, he’s the guy who fucked up the Unabomber. It’s a strange world.

KUPPER: MK Ultra is a very interesting program.

WILLIAMS: There’s also one that’s called Project Artichoke, which is a subsection of it that was run from the Edgewood Arsenal, which had more to do with weapons capability. That’s where the BZ experiments were. You’ve seen that film, Jacob’s Ladder? It feels recent to me because I’m 50, but 20 years ago there was a film, which I thought was semi-fictional. It was a magical realist account of the survivors of psychedelic experiments that the military did upon Vietnam veterans in the field, where they sprayed them with this hallucinogenic gas called BZ. I can’t say what that’s short for, but it’s essentially a weaponized, vaporized, pressurized version of—and super strong version of a hallucinogen like LSD. They sprayed them in a field and they ripped each other to shreds. And there are still people around who have these terrible, terrible flashbacks and they didn’t realize until relatively recently what it was. Not until the Freedom of Information Act - or whatever it is America sent here - that the documents were released and the American military acknowledged that they experimented, in the field, with super hallucinogens. Airborne, super hallucinogens to see what effect they had in the field.

KUPPER: Each one of these objects seems to have some sort of power to it. It ties into people’s desires to collect these objects.

WILLIAMS: One would like to think that. Hopefully I’m presenting these things and making them seem as desirable as they should be. Partly, I’m resurrecting something, if I can get a bit structuralist, that resides within the object. I would never classify myself as being as clever or as insightful as Roland Barthes, but there’s an example of somebody who could write about the color blue, or wrestling. But these objects do have a certain power.

KUPPER: I’m a packrat, I collect everything. Art, ephemera, to the best of my budget. There’s a certain power that these objects have. If you’re not a collector, if you don’t have that desire, it doesn’t make any sense.

WILLIAMS: With Julio of course, he would come into the shop out of the blue. I’d try and get things ready for him, he would stand there and I would say, “What about this?” “Yes.” “What about this?” “Yes. Yes. Yes…” I took him to a room once and he bought the whole room. You try to put them all in these bags and get them on Eurostar. It was great.

KUPPER: He was probably a great client to have.

WILLIAMS: And a nightmare as well. For me, Julio was not just a puppy on Christmas, he was a dog for life. For me, I would just want to make a small percentage with occasional quite good scores on things that I discovered. I knew this was forever, and he died early.

KUPPER: How old was he when he died?

WILLIAMS: 51, he was kind of my age now. So, even with all that money and privilege… it’s very sad.

KUPPER: At least he lived to the best of his ability there.

WILLIAMS: No, no, no, you’re right. He’s yen to experience and that’s the right word, he’s yen to experience. The descriptions of altered states of consciousness, inner journeys, or travels or whatever he called them, he maximized them.

KUPPER: I wanted to ask you about the counter-culture and what they think of this ephemera being in the hands of this billionaire family, or this wealthy guy that’s basically a part of the establishment.

WILLIAMS: I don’t know if I should say this on or off the record—they didn’t like it until he wrote the checks. They quite liked it. Sometimes they got angry afterwards. Instead of getting somebody like me to suggest what it might be worth, they blurted out a figure that they thought was impossible, and then he paid them. But they weren’t very happy when I suggested that rather than have a big boring building that we should have trains moving it around the world so that it could never ever be taken out and the whole world could share it, but the whole world would have to pay for it at the same time. We would share it with 10 different institutions at a time. It was bizarre in a way that these McLuhanites all wanted a library with a brass plate on it. That’s just collection-death. We did talk about the possibility of a Claes Oldenberg type syringe that would rise up and down on the outskirts of Geneva every night.

KUPPER: Last question, do you think counter-culture exists today?

WILLIAMS: To quote Jon Savage, “It’s when the posh kids and the rough kids get together that something happens.” And I could see in Washington Square Park. There were a few rough kids, girls, and then there were all these posh girls from incredibly privileged backgrounds. They want to do something, change something. I see a lot of hope in the young women of America and the world. I didn’t realize it then, but I think I do now. I hope I don’t sound like a twat saying that. It was a beautiful moment. I turned around and there’s a sea of faces of America. It’s weird with America, a bit like West Germany after the war, where you get this situation… Even Americans on the street look beautiful. Even the most messed up faces always have this incredible beauty about them.