What Does That Have To Do With Stephen Shore? A Conversation Between Stephen Shore and Roe Ethridge

photography by Roe Ethridge

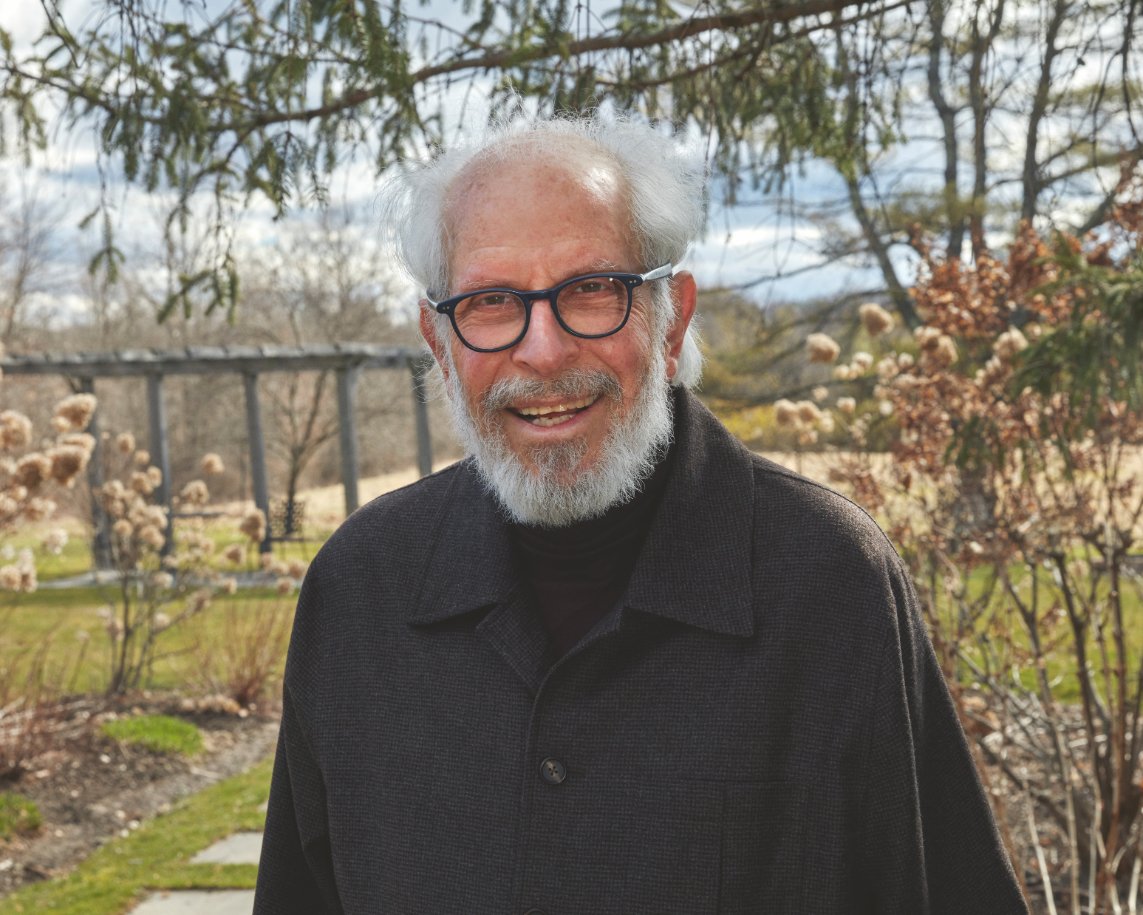

During the early days of the pandemic lockdowns, the legendary photographer Stephen Shore set out with a drone and captured America from above. A direct evolution of his famous mid-century topographic surveys of anthropogenically altered landscapes at street view, rendered in the rebellious realism of color, these new aerial expeditions captured the collective out-of-body experience of a global crisis. With a preternatural ability to train his camera to see the minutiae of the quotidian, there is always more than meets the eye. Shore’s new images unleash a refreshed and broadened understanding of humankind's tenuous relationship with nature. On the eve of his official departure from his ten-year-long Instagram project, fellow photographer Roe Ethridge visits Shore’s home in Tivoli, New York.

ETHRIDGE In the Topographies: [Aerial Surveys of the American Landscape] book, I noticed there are no sunsets and no sunrises. It's all basically the middle of the day. There’s something about the ordinary, mundane palette that is almost anti-romantic or anti-poetic.

SHORE Well, with drone photography, there are some reasons for it. Because I'm photographing at around 100-to-400-hundred-foot elevation, I don't have foreground material. So, I can't delineate space by having something in the foreground and something in the background. I'm photographing a relatively flat surface out to infinity. So, sunlight and shadows help articulate shapes on the surface. Also, I never photograph looking straight down, becausethat tends to abstract things. In terms of limitations, there are three pictures you can take with the drone: straight down, horizonless at a 45-degree angle, and with the horizon. It’s this game with very interesting visual restrictions. The other thing I love about the drone is that I don't know what is outside the frame. The drone is half a mile away from me, but I'm seeing exactly what's in the frame. If I move the camera over a little to the right, I don't know what's coming in. It's a completely different experience than making the visual analytic decisions that I would make on a street corner.

ETHRIDGE When you have that Olympian view rather than the street view it tends to feel more detached. The mess is sort of cleaned up because of the distance, but at the same time, it's like, oh, but we're just so small.

SHORE I like that idea of the Olympian view because it means that there is an entity viewing it; it’s a little more specific than a god’s eye view. Also, it's not aerial photographyfrom the view of a plane. It's a lot closer. It’s the view you get forty-five seconds after your plane lifts off. Things are recognizable, but it’s a different perspective.

ETHRIDGE It also makes me think of the history of aerial photography, like Julius Neubronner’s invention of pigeon photography in the early 1900s. So, seeing this view from above is not entirely new. There are tons of paintings of views from mountains looking out. I also think about The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) by Thomas Pynchon. There’s a character looking over this area of California and talking about how it looks like a circuit board.

SHORE Also, the relationship between natural and man-made features becomes clearer. What happens when a river goes through a city? What does it look like when a residential neighborhood meets an industrial neighborhood?

ETHRIDGE When you're on a street corner, it's like basketball, you have some moves that you can do. With drone photography, it's the pure discovery of this circuit board landscape that must be full of constant surprises. There’s also this mint green palette. Even the cover of the book is minty.

SHORE It's very interesting because I'm teaching a color class now. I haven't taught color in about twenty years. The students todaydon't even think about it being “color photography.” It's just photography. So, I want them to be able to stand back and think about the color. Color can be interesting, but if the picture is just about the color, it's completely uninteresting. That's what an earlier generation, people like Pete Turner, were doing in the ’60s. Young people are putting a frame around the world and not thinking of it as having a color structure. I want them to see the palette and take pleasure in the palette, but not take a picture that is only about the palette.

ETHRIDGE I honestly don't think about it that much at this point. For me, it was also the timeframe that I grew up in, the wallpaper in the house that I grew up in—the ’70s and ’80s palette. I can see it in howI make pictures.

SHORE It relates to something I wrote about in Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography, which is that you work on something as an artist, or even as an athlete, and then you internalize it.

ETHRIDGE I also see you in my work sometimes. I recognize it. So, thank you for that. It’s like how David Bowie said he was an amalgamation. I'm not David Bowie; I'm a hundred different people I took from, like Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol, and this person, that band, that painter. I took one of your little chestnuts and kept it for myself. (laughs)

SHORE That's how all art works. Speaking about Warhol, it hadn't occurred to me what an influence on you he was. But it makes perfect sense.

ETHRIDGE But you were there at The Factory! I read that funny quote where you were saying you and Andy would ride in taxi cabs going Uptown in the middle of the night after the late-night parties. He lived with his mom and you lived Uptown too.

SHORE I was the only one in the group that would wind up going Uptown. There would be activities every night. We'd either go to Chinatown or Little Italy where there'd be restaurants open all night. At some point, people would disperse. Andy lived on Upper Lexington Avenue and I lived on the Upper East Side. So, he would drop me off at home. But we'd have these completely unguarded conversations. The one I remember most clearly was when he was shooting Chelsea Girls (1966), and he decided to show it on two screens. He said, “Oh, Stephen, my films are so boring.” I asked him, “Well, why are you going to show it on two screens?” He said, “Because my films are so boring.” So I said, “Well, why don't you edit? He said, “Well, I don't know how.” (laughs) I had already read theoretical essays in Film Culture magazine about the meaning of boredom in Warhol films. And here I am, maybe seventeen or eighteen, sitting in a taxi with Andy Warhol, who I've read all this stuff about, and he’s talking about how boring hisfilms are.

ETHRIDGE What an experience, dude.

SHORE I was at The Factory on and off for three years. All my closest friends were either in The Factory or Factory adjacent. But Andy would come in every day and work. People had the idea that it was just a bunch of parties. He went to parties, but during the day he worked and he experimented. He tried new things constantly. The first time a video camera ever appeared in my consciousness was at The Factory. I mean, he was working with Billy Klüver at Bell Labs on the mylar pillows. When he was doing the cow wallpaper, he would try dozens of different color combinations. So, I got to see every day what it's like to be an artist.

ETHRIDGE I feel like adolescence is when you get to refine your aesthetic. And what an incredible thing that you were there witnessing this.

SHORE Andy was often impatient with people hanging out there. Once in a while, he put up signs by the elevator saying, “Unless you have business here, don't come in.” But he never enforced it. So, there were people who would come and sit on the famous couch all day staring into space, waiting for something to happen in the evening. But that's not what Andy was about. I felt a kind of connection to the cultural attitude he had. He wasn’t being cynical or derogatory about it—it was just a kind of detached interest in how things worked out in the culture at that moment.

ETHRIDGE Was he doing drugs?

SHORE As you're saying this, I have an image in mind. There used to be a chain of restaurants called Schrafft's. There was one on 57th Street and he would occasionally take me there. He was doing ads for them. It's the kind of place where your maiden aunt would take you for lunch. I remember him opening a beautiful enamel pillbox and taking his amphetamine. At The Factory, we had Brigid Berlin running around with a hypodermic needle sticking people, which is why she was called Brigid Poke. But he took it almost like medicine—in a very genteel way.

ETHRIDGE He stuck so hard to these short, three-word answers. I think it's hilarious. But did he think he was hilarious?

SHORE It's hard to know exactly what my memories are. It was almost sixty years ago and I was a teenager. But as you’re saying this, I remember I was living with my parents and I would have parties sometimes. Andy would come and chat up my father who was an investor. And he got the idea that my father would bankroll The Velvet Underground.

ETHRIDGE No shit.

SHORE The Velvets kept financial books because they wanted to be a grown-up, serious rock band. So, Andy gave my father the books. My father called me over and said, “Look at this. The last entry every day is $10 for H for John's toothache.” (laughs) You can deconstruct that in a few different ways. First, they wanted to be so serious that they would put in heroin as an expense. Second, they recorded it in the books. Third, they justified it by making it for John’s “toothache.”

ETHRIDGE Can I ask you about AI? Is it forbidden in your classroom?

SHORE It’s not forbidden on aesthetic grounds; it’s forbidden on pedagogical grounds. In my class, we start with film. For the first two years, the students only work with film. They have to spend a semester working with a 4x5 camera. We want them to get the basic craft down. AI might be an interesting way of producing a picture, but it's not learning photography. I don't really believe it's creative. The AI work that I have seen that's meant to look creative reminds me of second-rate art fairs where the stuff on the wall looks just like art. If you didn't know any better, it could almost fool you.

ETHRIDGE But it doesn't make a sound. It doesn't have a feeling. It doesn't speak to you. It's mute, in a way.

SHORE But I think it's a lot more complex than a camera. You need to understand its predictability. I can see an artist giving it instructions that will then produce art.

ETHRIDGE It hit me recently: the Renaissance was essentially technological. It came from the idea for the camera obscura. Now, maybe not everyone had a camera obscura so that they could do lifelike drawings of figures in space, but the point was that it was a tool. I love the painting, The Raft of the Medusa, by Géricault. It’s a great example of a reportage painting; a journalistic image of a shipwreck. And I bet he used a camera obscura to draw those figures because they are very posed. It wasn’t like someone doing gestural work in their studio—it was organized. It reminds meof Warhol’s Factory, but maybe instead of drugs, people were hanging around playing lutes or something. But I have used Midjourney for a couple of things. My prompt was a protest in Paris in the style of Roe Ethridge. It's pretty terrible what it gave me,but there are a few of them that I love. It's a bit uncanny. I can't get excited about prompt photography in general, but as a tool, I think it’s really amazing. I'm trying to incorporate it into my next show, but my gallery doesn’t like it. (laughs)

SHORE We referenced basketball before. Do you like basketball?

ETHRIDGE I do like basketball, but I'm more of a college football person, Perhaps because I played football when I was growing up—wide receiver and defensive back, but more defense. Iwas doing a lot of colliding with people (laughs). But then, I fractured a vertebra in my back. That was the turning point for me because I had already been interested in art, but my parents wanted me to be a good, Christian, Southern boy and play football in college. As soon as the CAT scan showed that I broke my back, I was like, “I'm not doing this anymore.” And then, I started taking the codeine stuff and that was my gateway into experimenting with drugs.

SHORE How did you start getting into commercial work, and when did you think about integrating commercial work and artwork?

ETHRIDGE I was living in Atlanta assisting catalog photographers. I had gone to art school and assisting was the only way to make money as a photographer. It was allcatalog work, down and dirty. I have this memory of assisting on a JCPenney catalog and there was a lady from the Texas headquarters over my shoulder yelling to the model, “Smile, honey.” Then, I moved up to New York in ’97, assuming I would be a starvingartist for a couple of years before I tried to get into Yale or Bard at a graduate level. I was making my little conceptual photography projects and showing them at a gallery called Anna Kustera on Wooster Street. I was also assisting a photographer named Jason Schmidt who said I should show my work to Pilar Viladas at the New York Times Magazine. She was like, “Okay, great. I have this textile story coming up. Can you do that two weeks from today?” And I was like, Oh my god, she doesn't know I'm not a photographer—I thought you needed a union card or something (laughs). Then, I had an assignment to do a lipstick story for Allure and the model showed up with her lips totally chapped. And at that point, I was thinking about the delivery system of imagery and how commerce and photography were in this sort of dance. Moreover, pictorialism was pretty taboo—it was like, what does that have to do with Stephen Shore? (laughs) I also discovered Paul Outerbridge who was my spirit animal. And then, Russell Haswell used an image from that lipstick shoot for the Greater New York show at MoMA PS1 in 2000, and that got things going.

SHORE I'm jealous. (laughs) I get one commercial job a year. I just did one for W. It was the fall fashion issue, all accessories, like shoes and bags. And I shot it all around Tivoli.

ETHRIDGE Can we talk about how you used Instagram? You left Instagram last night and posted a goodbye letter to your followers.

SHORE I thought it was time to leave. I've been on Instagram for ten years. In those days, the images were square and I hadn't used the square format in years. Part of the discipline was to post every single day and not do any self-promotion, no greatest hits. The format reminded me of the Polaroid SX-70. Not just in the look, but in the feel. There was a lightness to the SX-70. You could photograph the light hitting the glass and it would be just right. Polaroids weren’t expensive, so you could give them away, which is also like Instagram. After about six years, I found that I began to repeat myself in my work. I was falling into Instagram strategies. I stopped doing it daily, but occasionally I would post other things. At this point, I had over 200,000 followers and I was a mini influencer. (laughs) But I was spending too much time on it—it was becoming an addiction.

ETHRIDGE It has changed for me too. I don't think I ever really settled on a way to use it for myself. I didn't get on until late 2015 because of the square. Before that, I wasn’t able to post rectangular images. But it turned into more of a mix of personal and promotion. It's a ubiquitous part of being a commercial photographer. But I can't get off the thing. I'll be watching TV and then suddenly realize I'm looking at reels while there’s a show on.

SHORE I know—part of me will miss stupid panda videos. But I'm leaving the page up because it was an art project and I want that art project to be archived and seen in the form it was meant to be seen, as opposed to in a book. I felt I needed to post a statement so that people don’t take it personally when I don’t “like” back. I didn't want to ghost anyone

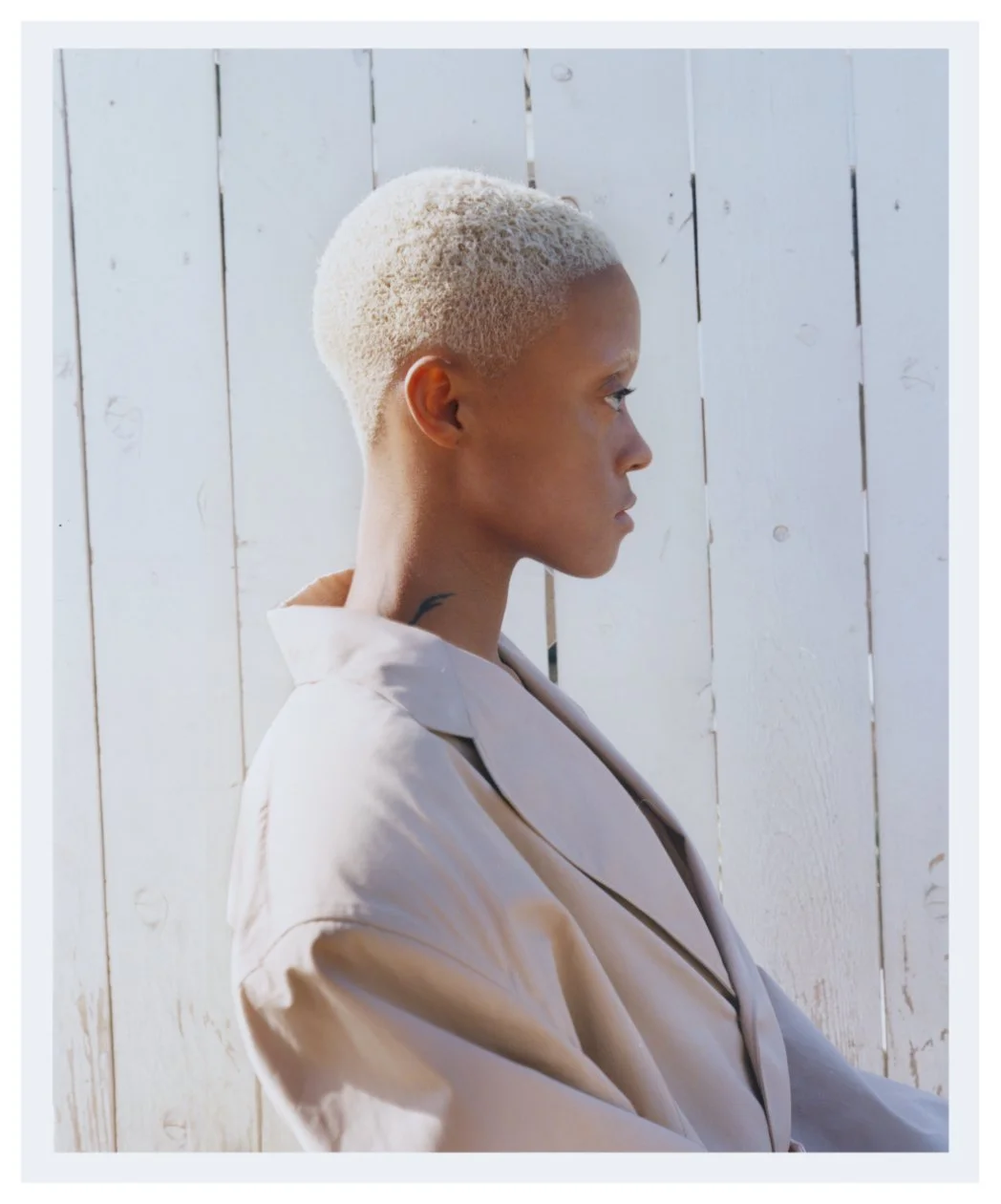

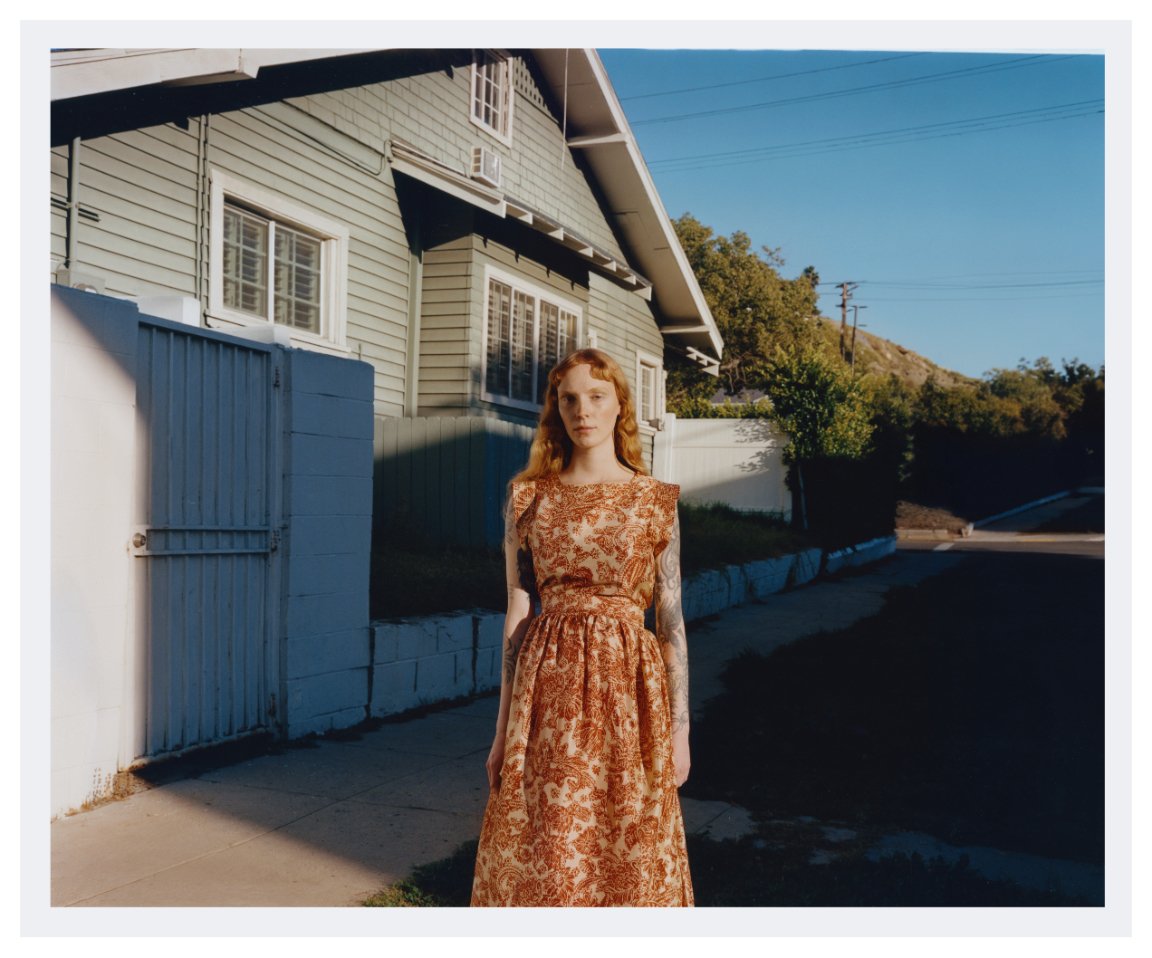

ESTATE SALE

styled by Cathleen Peters

photography by Sergiy Barchuk

lighting assistance by Joseph Miller

set design by Mat Cullen

set assistance by Kevin Kessler

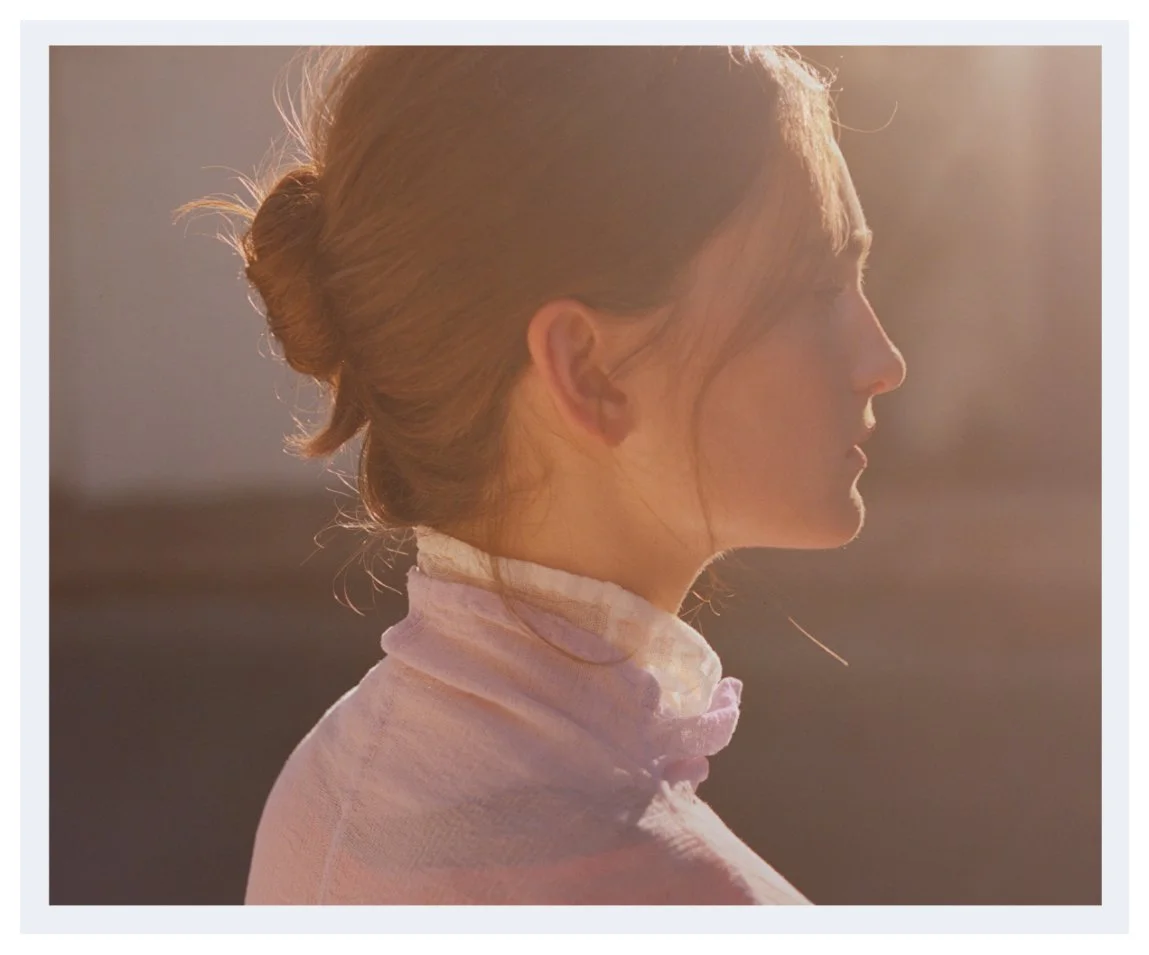

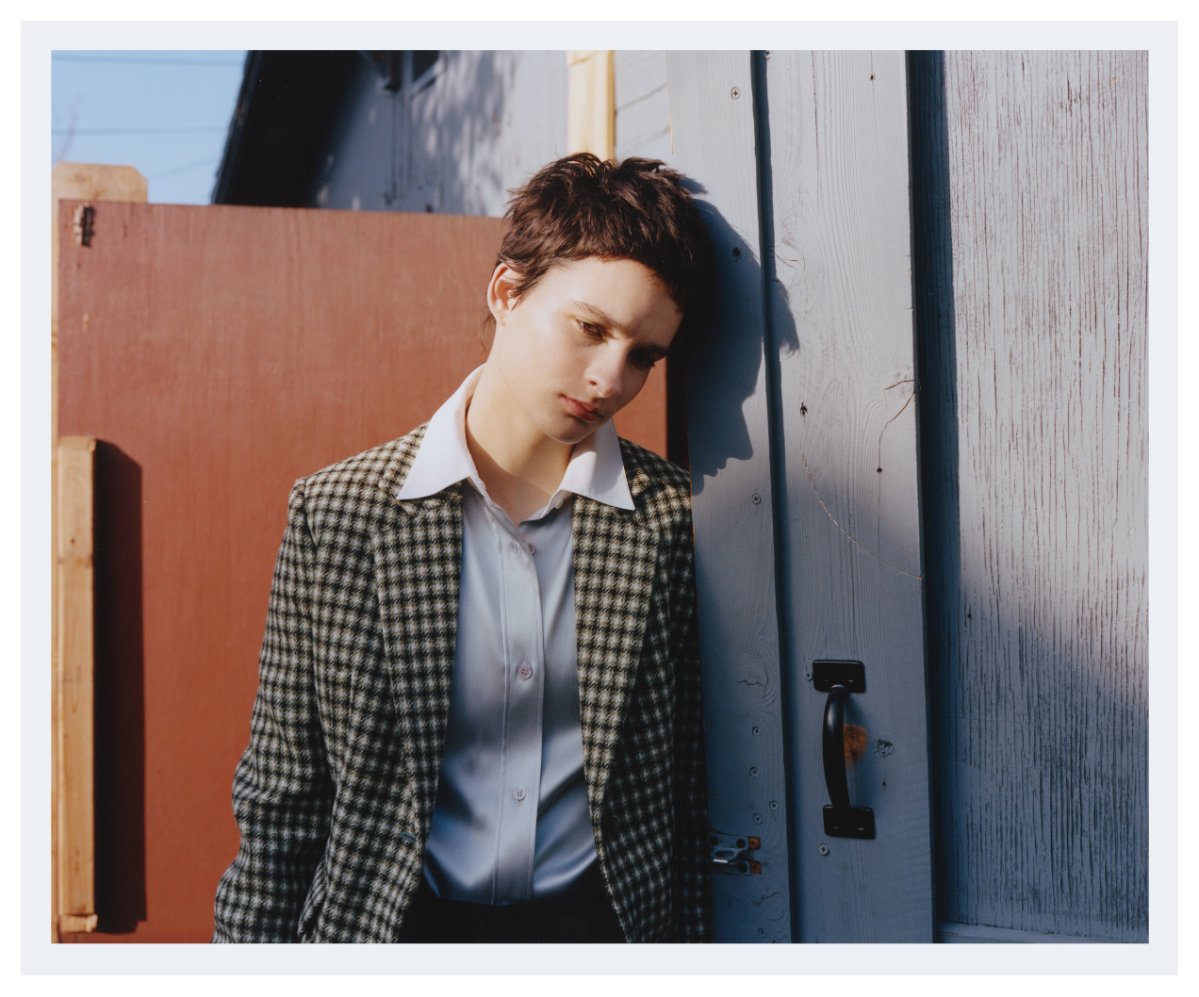

WHO IS CHARLI XCX?

Hair: Matt Benns, Makeup: Rommy Najor, Styling Assistance: Amy Bialek

Born Charlotte Emma Aitchison in Cambridge and raised in Essex, Charli xcx is one of those rare superstars that defies genre categorization. She sways effortlessly between the experimental and the mainstream, the serious and the irreverent. Her rise, and rise, and rise, since releasing the first demo via Myspace in 2008 at the age of fourteen, has proven that a particular indistinct classification may be the key to her success. But who is Charli xcx? Pop star or performance artist? We enlisted her closest friends and collaborators to offer clues through quotes, tweets, and behind-the-scenes photos. On the occasion of Charli’s upcoming album, BRAT, a follow-up to her 2022 chart-topping album CRASH, Hans Ulrich Obrist examines the artist’s inspirations and solicits her advice for younger generations.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST How are you?

CHARLI XCX I am good, thanks. How are you?

OBRIST I'm good. I'm very excited to finally meet. We have so many friends in common. Where are you?

CHARLI XCX I'm in an Uber in South London and I'm going to East London. I imagine that you know my friend Matt Copson.

OBRIST Yes, I know Matt Copson and Caroline Polachek. I'm going to tell them that we met. They will be excited.

CHARLI XCX Nice, nice. Cool.

OBRIST I wanted to begin with the beginning. How did you come to music or how did music come to you—because you started so early? Was there an epiphany?

CHARLI XCX I think the reason I wanted to make music was because I wanted to be cool, really. I always just felt like such a loser. Also, I was enthralled by certain artists who I loved on Myspace. I was just at home in the countryside, living out this fantasy life through other artists that I would listen to on Myspace. I wanted to make music in the way that they made music; that made me feel like I was living in a film. And so, I just started trying. At first, I failed terribly because I wasn't really a producer. I didn't have an understanding of sound or anything, but I knew that I was trying to capture this feeling of excitement. The feeling of listening to music in the back of a car, and looking out the window, and immediately feeling like I was in a music video. I was always very against the idea of needing music to survive. But now, the older I get, the more I need music to keep me sane and functioning. It does really help me air out a lot of anger and emotion that I have.

OBRIST In all art forms, the future is sometimes invented with fragments from the past—we stand on the shoulders of giants. I read that Björk inspired you. Also, Britney Spears. I am wondering if there are other musical artists, but also artists from other disciplines, that have inspired you.

CHARLI XCX What I've learned about myself recently, particularly during the making of this record, is that I'm not actually that inspired by music. I'm inspired by the careers of artists like Björk. I'm inspired by her position in culture—what she has done for female auteurs in music. She carved a lane for herself and has been really defiant in the choices that she makes. I'm inspired by Britney because I'm fascinated by pop culture. I like looking at pop music and pop culture through the lens of society. That's the thing that gets me really amped up. Lyrically, I adore Lou Reed because he was looking at all of these people in New York—these amazing characters who were so fueled by drug culture, punk culture, by the culture of fame—and he was writing this incredible poetry about them. I think I write my lyrics from that same perspective. I went to art school at Slade [School of Fine Arts], but I dropped out after a year. I was always gravitating towards performance artists. I also really liked Alex Bag and Pipilotti Rist.

OBRIST In an interview recently, you mentioned that music isn't as important as artistry; a great artist is more than the songs they make, it's the culture they inhabit. That’s, of course, the case with Björk, whom I met in the ’90s when I was a student. I went to her gig at Rote Fabrik in Zurich, which is a totally alternative space. And then, a few years later, she was super mainstream. But she never stopped experimenting. With your work, I feel like there is a similar oscillation.

CHARLI XCX There is this pendulum within me that swings from caring about commerciality to not caring about it at all. And then, there is this thing where I gravitate only to what I love. I love Britney Spears, but I also love Trash Humpers (2010) by Harmony Korine. He's interesting because he plays with pop culture in a very glossy magazine type of way. And I like high and low. I think that's what I was actually trying to do at art school when I was there. I was putting pop music in a more traditional space. A lot of the people that I was at school with were interested in classical painting and I just wasn't at all. But it was fun to play in that realm with pop music and literally sing Britney Spears songs in my crits next to people doing these huge fucking canvases that were always brown, which bothered me.

[Charli’s phone cuts out]

OBRIST Hello? Can you hear me? I lost you.

[Fifteen minutes later]

CHARLI XCX Hello? Oh my God, I'm so sorry. I just went through a tunnel and then my phone just gave up on me, but I think I'm back now.

OBRIST No problem. We’ll do the interview in different parts. (laughs) It's now part two. So, where are you now?

CHARLI XCX I'm now in East London. So, part two is in East London. (laughs)

OBRIST I wanted to talk about collaboration. I have been doing studio visits with visual artists lately and everybody has these amazing collaborations going on. And your new album is a continuation of these amazing collaborations you’ve had for a long time, whether it’s Caroline Polachek, Kim Petras, or Troye Sivan, and your very special collaborations with SOPHIE.

CHARLI XCX Collaboration, in general, has always been really important to me. When I was younger, I was very much searching for this crew of artists that I wanted to surround myself with. I felt like a lot of the people who I was looking to, whether it was artists signed to Ed Banger Records, there were this group of people who were working separately, but also collaborating and weaving in and out of each other's worlds. I was searching for that for myself, but never really found it. So, I kind of realized, okay, maybe I have to sort of create this for myself. And it was only when I met A. G. Cook, and I saw he was doing a similar thing with PC Music that I felt like, okay, we have a very similar outlook about the way that music can be made. You can bring your friends in, you can work with other artists really in a very low-stakes way without ego—just because it's fun, and I began doing that. Caroline, for example, is someone who I've collaborated with a lot and we work in possibly the most polar opposite way, but it works. She is so detail-oriented and in the weeds. The way I work is very instinctive and spontaneous, but then I literally will never revise a single thing. Whereas Caroline is such a perfectionist. It's fun to work with her because she makes me think about things that I wouldn't normally think about.

There is one song, in particular, on the upcoming album that is about SOPHIE. And that song is about my dealing with the grief and guilt around her passing. She has obviously been such a huge inspiration in my creative process across the board. I think this album is a kind of homage to club culture as a whole. And, of course, she was an extremely big part of my experience of club culture along with many other artists, including A. G. Cook and a lot of French electro artists like Mr. Oizo, Uffie, and Justice. But while this record is about club culture and partying, it’s a very brutalist take on that. It’s very raw, confrontational, and in your face. What all of the artists have in common, which can be felt through this record for me, is this element of confidence and commitment to doing exactly what you feel in a very fearless way. That's something that SOPHIE was always encouraging, not just with me, but all of the people that she worked with.

OBRIST You said that in the previous album, you were moving away from hyperpop. Is the new album moving further away? How would you describe the music of the new album?

CHARLI XCX I don't pay too much attention to genres. To me, it's a club record. I understand that some people need to define the music. There are some pop songs on the record, but this is stuff that I would play in a club. It’s very much electronic. It's very much dance music. It's abstract in some ways, but in other ways, it's very tangible. There are elements of it that are super repetitive, but then there are also these really kind of blossoming, flowing melodies. It's my take on club music.

OBRIST Do you have any unrealized collaborations or projects?

CHARLI XCX I have so many. (laughs) Firstly, the fans don't know it yet—I guess once they read this interview, they will—I am releasing a lot of my demos that won't make it to the album and playing them at my shows, at my DJ sets. Just to show that there are a lot of tracks that don't make it—not because they’re bad (in fact, some of them are really good), it's just that they don't fit with the record. I'm into the idea of this massive amount of material being out there, saturating the fan base with all of these things that could have possibly happened. In terms of other projects outside of music—I acted in my first film last year, called Faces of Death. And that has spun a wheel for me. I was very afraid to explore that side of myself for quite a long time, but now I really want to act. And that put me in this zone of writing a script. Also, I went to Italy for six weeks to write my book, but then I ended up just drinking Aperol spritzes all day, every day, and chain-smoking cigarettes. I think I wrote the beginnings of two chapters and then gave up (laughs). But there are a lot of projects. Right now, there's this film I'm beginning to formulate in my brain, and that's probably my biggest project that hasn't been realized yet, but I'm hopeful that it will be.

“That's what good music does. You can be as clever as you want, but the important thing about art, in general, is the feeling and conviction.” - Charli XCX

OBRIST I'm really interested in the connection between music, literature, and poetry. I just had a long discussion with Lana Del Rey a few weeks ago. Lana, of course, wrote this very beautiful poetry book. In a recent interview, you mentioned books by writers like Rachel Cusk, so I am interested in your connection to literature. And do you write poetry?

CHARLI XCX You know, I don't write poetry. I mean maybe some people would say that song lyrics are poetry, but I tend to think of poetry in a more traditional way. And I don't feel that I'm a poet in the way that a lot of people would call Lana Del Rey a poet. I don't feel that I'm operating in that same sphere. But I think my favorite author of all time is Natasha Stagg. I really like the energy of her writing—it just feels very visceral but very blunt at the same time, which I absolutely love. When I'm reading her essays, I feel like I'm in a conversation with her. That’s my favorite kind of writing, those are my favorite kind of song lyrics. It's why I love Lou Reed's lyrics. I feel like he's talking to me, and it's why I really feel quite strongly about the lyrics on this record that I've just made. They feel like I'm texting my friends. If I was ever gonna write this book, I think it really would feel like a kind of group chat, like a flurry of iMessages. (laughs)

Araks Bloch Malone Souliers Shoes

OBRIST Now the topic of this issue is levity, which has to do with high spirits, but also vivacity, which has to do with one of my favorite virtues, which is energy. Your work is so full of energy. Can you talk a little bit about what the word levity means to you and its connection to pop music? Do you think that music can bring levity to people in the form of positivity or optimism, as opposed to doom?

CHARLI XCX It's funny, when we were shooting the images, everybody was saying the word levity a lot. The stylist, the photographer, everybody was sort of saying, “Remember levity.” Which is sort of funny because I don't smile in pictures. And I was like, “Yeah, yeah, totally—it's in my head, but it's not coming out of my face.” There is such a joy to music and a lightness to the feeling that it often brings people. Even when I get so bogged down by the theory behind what I'm doing, like the reason I make my album cover, the things I say, my lyrics, and the production choices, at the end of the day, I gravitate towards all of it is because it's fun and it makes me feel something. That's what good music does. You can be as clever as you want, but the important thing about art, in general, is the feeling and conviction.

OBRIST Caroline Polachek works a lot with Matt Copson who created these gorgeous volcano visuals. Musicians often use visual art, or do visual art for their stage sets, or for music videos. I’m curious about your own visual art and also your collaborations with visual artists.

CHARLI XCX On this record, and the past few albums, I've been working with Imogene Strauss on building out the entire visual world. Sometimes we'll go super in-depth with another collaborator. For example, the music video I made for my first single from this record, “Von Dutch,” was something I worked on with Torso. I had this idea for it, and I knew they could pull it off because their camera work is so intricate. I filmed little pieces of it on my iPhone and would send them to them. I would put the phone on the ground and walk over it—demonstrating to them exactly how I wanted it. The album cover, for example, was made on my iPhone in June of last year. I don't use Photoshop. When it comes to computers, I'm not very skilled at all. So, I made the cover with this app on my phone. We went through a million different iterations of this green square that had the word ‘brat’ on it with this design company called SPECIAL OFFER, inc. Eventually, we just came back to the version that I made on my phone. But I enjoy sharing things with my friends and going back and forth with them, even if they're not really in the art world. That's fun to me. Also, I’m sharing music with people who don’t have anything to do with music. Getting opinions on music from visual people, like photographers, is interesting. And getting visual opinions from musicians is more fun.

OBRIST When I was about sixteen, I started to curate and visit art studios. But I was so lucky to have these mentors who gave me advice. And you, of course, started even earlier. Rainer Maria Rilke wrote this book, which is advice to a young poet. A lot of young people are going to read this interview. Given your huge amount of experience, I am wondering what kind of advice you would give to someone who might be sixteen today and wants to be an artist or a musician.

CHARLI XCX I would say, there’s no rush to create. You have your whole life to create and maybe you'll make your best work when you are fifteen years old, but maybe you'll make your best work when you are ninety-five. There's no peak in creativity. Obviously, in pop music, especially for women, there is unfortunately this kind of time bomb on age, this myth that women are at their peak at a particular age. But I don't agree with that and I think it’s changing—it’s just an awful trait of the industry that still lingers over us. But it's not true. I mean, it doesn't matter how old you are, you can still create great work from a really unique perspective as long as your perspective is interesting and as long as you're true to yourself. There's no timeline for creativity. When you are ready, you’ll know it deep within you; when you feel the most confident and fearless. But that also takes a lot of trial and error. You have to work your craft in whatever you're doing.

“I don’t think you know that you're going to be part of a cultural moment before a cultural moment happens. Otherwise, it probably wouldn't be one.” - Charli XCX

OBRIST That's great advice. Today, we had a conversation here with Alex Israel, another friend we have in common. He was saying how important it is when he makes a feature film or does an AI project for a big brand like BMW, his art can reach many more people than just through the visual art world. And that's also true for music—for example, when you did that amazing song for Barbie (2023). You reach hundreds of millions of people who might otherwise not encounter your work. So, I wanted to ask you about that as a strategy to reach many different worlds and bring people together. I think the world is too fragmented and separated, and we need to bring things together now.

Balenciaga

CHARLI XCX It's interesting. I actually didn't really have a strategy, but it's totally smart to think of it like that. I’ve known Mark Ronson for a long time—he reached out to me and said, “There's this driving scene in Barbie. Greta Gerwig thought of you, do you wanna do it?” And was like, “Yeah, sure.” But in my head, even though at that point they had Nicki Minaj, Ice Spice, and Billie [Eilish] on the soundtrack, I still wasn't thinking, oh this would be a smart thing for me to do. Even though Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling are in it—and Greta Gerwig is directing. I was just like, okay, I love doing driving songs. I can do that. And I like Barbie and driving scenes—that’s the only reason why I did it. It didn't feel like this high-pressure, massive, multimillion-dollar budget movie thing. It felt like me and EASYFUN, who I made the song with at my boyfriend's flat in Hackney, making this song in forty-five minutes and then him spilling coffee over the white sofa before he left. That was the day. And then, it comes out and it catches fire, and you're like, Oh my god. I'm part of this cultural moment. I don’t think you know that you're going to be part of a cultural moment before a cultural moment happens. Otherwise, it probably wouldn't be one.

OBRIST We haven't spoken yet about you as a DJ. I was in Milan and Erykah Badu was DJing at a Bottega Veneta event. She makes music and does concerts, so it was really interesting to see her DJing. Recently, your Boiler Room DJ set went viral. Can you tell our readers and me what it means for you to DJ?

CHARLI XCX It's one of my favorite things. I actually hate going to live shows; I just love watching DJs. I grew up listening to 2manydjs and Soulwax mixtapes, and it would always just make me feel so alive. And the sound quality—listening to a DJ is always better. It makes me feel so much when I see a good DJ playing good records and controlling the crowd with their own choice of music. It makes me wanna party and get fucked up. But also, I don't need to do that if I'm watching a really good DJ because I just feel so elated and in the zone. It is totally joyous for me and I love it when I get to do it. And the Boiler Room thing, I was definitely very nervous because there were a lot of cameras in our faces, but we had a really good time.

OBRIST Amazing. Thank you so much. It was such a great conversation. I really hope we can meet in person. I can show you our shows at the Serpentine and maybe have a coffee.

CHARLI XCX I would love that.

Like a Kid or a Caveman

text by Angelo Flaccavento

As an outer skin that one can discard and change as fast and as often as one wishes, there is an inherent levity—certainly a frivolity—to clothing, and with that, more broadly, to fashion, which is electrifying, reassuring, and elating, even. And yet, in the current climate of heavily branded storytelling, of fake intellectualism as a cover-up for a disheartening lack of ideas, neverending recycling of old ones, and plagiarism of identities, levity is nowhere to be found. Everybody in the system, designers in particular, but also critics and commentators, aspire to the role of deep thinkers, or gurus with hoards of followers to indoctrinate. They all bring the discourse to philosophical heights and unprecedented ideological peaks, probably neglecting the fact that what we enjoy managing is just items of clothing, expressive signifiers of modernity with built-in obsolescence that will make them passé in a nanosecond; certainly misremembering that this is, after all, just fashion.

I am probably giving in to the same mistake here, and being quite heavy or moralistic in my thinking, so please allow me to clarify the aforementioned statement. I am adamant that everything about fashion is deeply philosophical and endlessly thoughtful, that visual language is as meaningful and piercing as verbal language, if not more, that the aesthetic is blatantly political and that the frivolous is actually ideological. I am also convinced that such qualities are high in density but very light in weight, almost weightless in fact, and matter exactly because of that. Considering fashion a heavy topic, somehow, is a way to defuse its power, to diminish its reach, to deactivate its seditious essence. The same applies to many other human activities, both creative and non-creative.

Frivolity matters, that’s the point. Floating lightly is the way forward: being as impalpable, constantly moving, changing and shifting as clouds; embracing impermanence. In this sense, with its silly fickleness, fashion can be an effective vessel for levity, a wonderful way to accept transience as a condition that frees us from the burdens of life and allows us to float and flow well above them, amusing ourselves along the way. What’s not to love about such a prospect? And yet, nobody wants to be taken lightly as of late, not even die-hard fashion victims. Levity and frivolity increasingly sound like a curse, an insult, when in fact, deep things hide on the surface. Levity is movement; frivolity comforts, offers ways to shapeshift, to be free from the constraints of being engagé; they are both, ultimately, so very human. Frivolity and levity are as bold in substance as they are light in impact. They are something that fluidifies, electrifies and beautifies the theater of social life in which we all take part as leads or in supporting roles, ready to change those roles as life commands, to embrace the unknown with promptness.

Why are we in a levity-deprived fashion environment populated by self-sufficient, pompous intellectuals, then? I have a theory. An exaggerated one, but still: the unwilling culprit in this killing of levity is Miuccia Prada. It was Ms. Prada, in fact, who brought culture, in the broader sense, within the realm of fashion. It was she who opted for intellectualism over the traditional fashion talk. By doing so, she created a potent identity for herself and her brand, so much so that many others emulated her, adopting, adapting, expanding, but ultimately distorting. What works for Ms. Prada is the result of a very personal way of thinking and an organic ideological path, but becomes a staged, fabricated, and rather forced affair for others. It becomes as heavy as lead: that’s it. But there is more. Despite being intensely intellectual, Ms. Prada has never tamed the fashion animal within her, nor the frivolity and levity that come with loving jewels, sparkle, glamor even. She is light and playful in her brainy approach, that’s how she creates her magic. She is the epitome of thoughtful levity. Her followers, meanwhile, only focus on intellectualism. They become cumbersome, self-centered, and unable to take it lightly in their penseur poses.

The kind of ego-pleasing self-punishment that many fashionistas have imposed on themselves when it comes to disdaining frivolity, humor and levity in favor of serious intellectualism and ideology looks to me like a renouncement of sorts, a freezing of energy. They just stop in their tracks to luxuriate in the contemplation of their thought process, refusing the inherent playfulness of fashion. It is a pity. Levity, after all, is the fuel that prompts movement, the exhilarating gas that releases the lightness of being at its full potential. Frivolity is bubbly; it acknowledges that changing opinion, style, or shape is acceptable. It is, quite simply, a self-standing and self-affirmative gesture of life devoid of any hidden meaning. It gives a zest of joy and the strength that comes from the magic of being alive and ready to align with the movement of the universe in ways that are immediate and spontaneous, almost childlike. There is a silliness to it that is positively juvenile.

Embracing this kind of childishness is not being silly, however. Just think of what Cy Twombly and Paul Klee achieved by unlearning, by letting their tools dance on canvas and paper in ways more suited to a kid, or a caveman. Levity is existentially weighty. It comes with the recognition that nothing lasts, nothing is finished, nothing is perfect. It’s very wabi-sabi and quite melancholic. Levity is the awareness that everything probably happens for a reason, but looking for that reason might take a lifetime, and in the end, one might not succeed in finding it, so we may as well dance, flow, float above it all like a feather.

Multiplicity is the essence of the human condition, and levity is probably the best way to slightly and readily grasp it. Clouds come to mind. As a changing of state that’s essential to the life of our planet, clouds can go from quiet to stormy in a flash, anticipating a versatile state of mind in which clear thinking, symbolized by water and air, can pass through any turmoil, come rain or shine, and result in a balance that is full of lightness and readiness. Levity is ultimately a way to accept everything as a process, rather than a fixed state. As such, it works perfectly well in fashion, as in life. In this token of writing, the focus has constantly shifted between the two, probably with a certain unruliness. That’s the sparkle of levity: a keenness and liveliness in shifting and adapting. And so on and so forth, until the very end.

Addictive Textiles

text by Bliss Foster

Everything about fashion has been a serious endeavor throughout my career. I discovered what I wanted to do with my life when I was in my early twenties. It was at this time that I realized clothes were not simply a practical tool, nor just a status symbol. Fashion, instead, can and should be an effective, brilliantly complex form of storytelling.

With an undergraduate degree in literature, I began looking for resources to learn more about the intellectual complexities of fashion design and the narratives within collections. I expected fashion to have a similar academic community; to find an endless quantity of people online discussing and interpreting runway shows, dissecting the meaning of seam choices, and decoding pattern construction. Yet sadly, deep analysis was nowhere to be found. No one seemed to examine fashion on a microscopic level and no one wanted to understand the conceptual mechanics.

Granted, at that time, I didn’t know about the excellent fashion theory work of scholars like Caroline Evans, Franchesca Granata, Shahidha Bari, Dana Thomas, Andrew Bolton and many others, who have all now become inspirations for me and my work. Truly thinking I was alone, I started analyzing fashion in my own way. I was relieved to find that fashion runways, like the literature I had studied in college, lent themselves well to analyses; there was plenty under the surface to uncover and, most importantly, I felt like I appreciated the runways even more after I had done extensive work to dissect them.

As quickly as I could, I made fashion analysis my profession. I began a series where I dedicated a twenty-minute video to each runway show by Martin Margiela, I released weekly videos where I wrestled with questions of theory, and I began traveling to Paris for runway shows every few months. Once I met my wife, Daniella, she kicked me into overdrive. Daniella is much more educated than me; her ocean-like knowledge and her laser-focused taste pushed me to new places. We started writing and making videos together and the work soared as a result.

Throughout my time in the fashion industry, I have been rewarded for rejecting levity. To be blunt, my brain developed a ‘fuck off’ policy towards any fashion that was cute, fun, light-hearted, or just functional. I wanted only Iris Van Herpen, Comme, Dries, Maison Martin Margiela, old Prada, Carol Christian Poell, Undercover, Deepti Barth, Craig Green, Rick Owens, Raf Simons, Final Home, and Yohji. Levity was for everything else; fashion deserved respect, damnit.

All this changed when I had the opportunity to interview an outstanding designer from Antwerp named Jan-Jan Van Essche. Jan-Jan’s life and business are what many starry-eyed fashion students think their life will be as a designer. Jan-Jan has a beautiful studio in Antwerp where he and his small team design, draft patterns, craft prototypes, and occasionally weave textiles on an in-house loom. They even take turns making food for each other. I was so struck by the pureness of Jan-Jan’s process, that I wanted to support them in some way. The clothes are priced fairly, but were still a little steep for me, so I settled on a long-sleeve t-shirt. While I was buying it, Jan-Jan’s partner in business and life, Pietro, told me, “Careful, that textile is addictive.” When I asked what he meant, Pietro said, “It’s a special blend of cotton and cashmere. It’s quite functional, but there’s nothing else that feels like it.”

If I’m honest, special blend or not, I walked away feeling embarrassed that I had spent so much money on a t-shirt. I even apologized to Dani, though she assured me that she wanted to support them as well. I didn’t think the shirt flattered me, so I tucked it away in a drawer and forgot about it.

Months later, I came down with an intense fever and was in bed for days. Daniella suggested I sleep in my new t-shirt. I resisted because I didn’t want to stretch it out. “You spent all that money and haven’t worn it once! It’ll be cozy, just try it on and see how it feels.” She was right. Since that day, I have slept in that same long sleeve for 137 nights in a row. And just as years before when I had come to realize the beauty of a collection's narrative and intention, I now understood the importance of textile and material.

I am now more aware of how narratives can be told through the haptic sense. The tactile experience of any given material can’t be properly appreciated by grabbing the fabric with your hand; that would be like experiencing a hot tub by standing in a puddle. Textiles can only be fully experienced by living with them, wearing them to stay home all day, outfit-repeating multiple days in a row, taking care of them when they’re damaged, and experiencing how the textile ages over time. Knowing now how radically different a well-considered textile can feel, I’ve become fixated on finding new tactile experiences with clothes. There is no academic pursuit that can provide more insight into these feelings than the experience itself, and with these sensations, there’s a heavy dose of levity. I’ve since bought a yak wool beanie, a few more cotton+cashmere long sleeves, and a pair of oversized cotton pants with a heavy wax coating (my viewers say it looks like I’m wearing a massive, wet paper bag—in a good way) all from Jan-Jan.

For the last five years, the seriousness with which I treated the fashion industry was a defining part of my personality. I felt it was what made me valuable to my viewers and the designers who I admired and critiqued. I’ll forever owe a debt to Jan-Jan Van Essche for showing me how to bring levity into my fashion life. It’s a debt I’ll likely pay off by slowly collecting his clothes. 2024 will hopefully be the year that I pull the trigger on an Icelandic wool sweater.

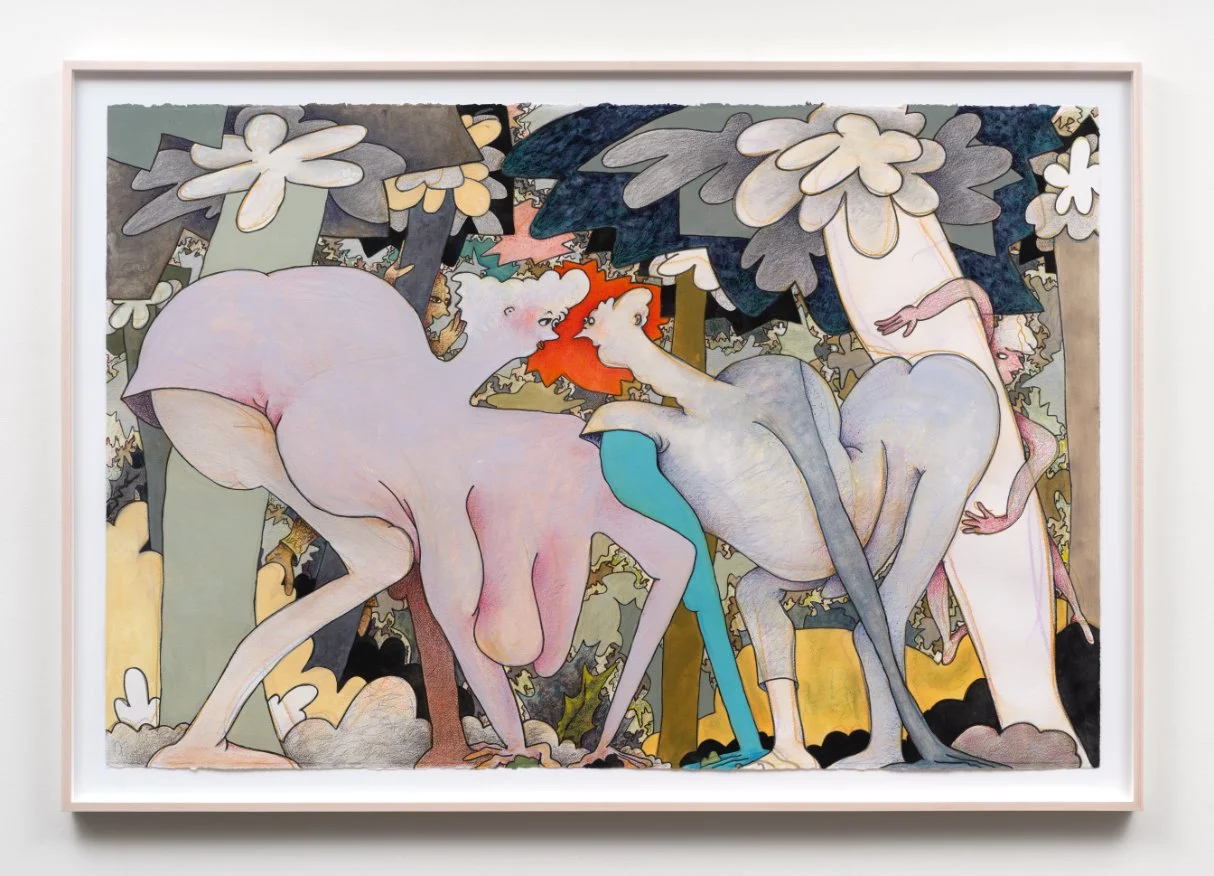

Jeffrey Gibson

interview by Nellie Scott

Jeffrey Gibson, a member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and of Cherokee descent, is the first Indigenous artist to represent the United States with a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale. Since the 1990s, Gibson has been weaving his own Native traditions and queer history with pop cultural references, particularly song titles, into kaleidoscopic textile works, paintings, videos and performances. His exhibition at the US Pavilion, the space in which to place me, takes its title from Oglala Lakota poet Layli Long Soldier’s poem Ȟe Sápa. In the following interview, Nellie Scott, the director of the Corita Art Center in Los Angeles, delves into Gibson’s history-mining practice.

NELLIE SCOTT In your work, you blend a rich tapestry of cultural influences, materials, and themes. How do you describe your artistic identity and vision and how has it evolved throughout your career?

JEFFREY GIBSON There are a couple of things that have happened recently, even in the past twelve months, that will serve as milestones for me, like the Venice Biennale and the publication of An Indigenous Present. So, I'm kind of thinking that I can move on to different aspirations artistically. It's a strange transitional place to be because I think for so long I've been pushing for different kinds of representation in the art world and trying to use every platform that I have to do that. I have outgrown a lot of the language that's been used to describe me and my work, which I have perpetuated myself. I think being a parent has shifted the way that I think about what I’m responsible for putting into the world and the conversations that I want to be a part of. One of the biggest things I would look at is the collaborations that I've done. I've learned a lot about what collaboration can mean. What kind of partner am I? I have always pushed for inclusion of Indigenous Queer voices and I think we're at a point now where we need everybody at the table. Culturally, we need all of the best perspectives for everything that we face in contemporary life.

SCOTT Your artworks often feature a striking use of language. A quote of yours that feels like such an embodiment of the infusion of pop lyrics, club culture, queer theory, and intertribal aesthetics into your work is, “How do you write a word that screams? How do you write a word that whispers?” Could you describe your process for integrating language into your art, and how you decide what words or phrases to incorporate?

GIBSON For some reason, other people's words articulate my feelings. I have been trained by musical lyrics and excerpts. I love brevity. But they used to be more plentiful. I would listen to music and they would just kind of jump out. It's almost like foraging now. I have to go hunting for words. I try to envision a personal sentiment that I'm feeling. Maybe it's something that comes up in my head or a theme. For instance, my body and other bodies are an important theme. Intimate space, anonymous space, public space, private space, introspective and internal space. And time—I don't feel old, but I do feel like when I turned fifty, there was a shift. Somebody described it as suddenly you're on a branch, looking at the end of the branch, rather than looking at where the branch is connected to the tree. With words, it's interesting—I have thought about Corita Kent a lot lately and revisiting scripture, in particular, the way that she used it. There were times when I didn't know it was coming from scripture. It felt provocative or it felt political. It felt progressive. We live in a time where it's so easy to get caught up in the minutiae of life and it’s decontextualized from the intentions and dreams of the future and historical narratives of the past. So, I feel like it's been very helpful for me to think about the voices of people, historically, who have proposed progressive ways of living and communing. I think what always drew me to popular lyrics, musical lyrics, was the way that they hit this mass saturation point of so many people being able to remember them, repeat them, relate to them, and feel themselves in those words. Now that I’m authoring my own writing, what are the things that I'm afraid to say out loud to another person for fear of sounding too sappy, too sweet, too loving, too trusting, too naive?

SCOTT Your work offers an invitation to the viewer to be present, often using bold colors and familiar materials. In your 2021 exhibition, It Can Be Said of Them at Roberts Projects, you drew the exhibition title from an artwork in Corita Kent’s Heroes and Sheroes series created in 1969, which features a quote from the New Yorker, “It can be said of him, as of few men in like position, that he did not fear the weather and did not trim his sails, but instead, challenged the wind itself to improve its direction and to cause it to blow more softly and more kindly over the world and its people.” Considering the legacy of artists like Corita, how do you see your work contributing to or diverging from this lineage of artists who blend art with social commentary?

GIBSON I think of the generation when I was studying art, the late ’80s into the ’90s. At the time, the phrase “the personal is political” was always being thrown around. And it resonated with me for sure, because of being a gay man, because of being Native American, because of being an artist. And then, there was something about that language that became outdated very quickly. It lost its punch. It never stopped being true, but I think at this time in history, when we think about things that are happening at the political level and how much they are about our physical health, our mental health, our decision-making, our own bodies, that statement continues to be so true. It's almost like it's become realized. And it's almost been reversed. Also in the ’90s, we were presented with the concept of didactic thinking. But the space of freedom exists in between, or on either side of those two points. And for me, that's where poetics happens. Poetics happens because we let go of these firm points that determine meaning, and we suddenly have to open up to fluctuating definitions. Nothing is fixed. You actually have to be somehow welcoming of the unknown. You have to be welcoming of the unfixed. You have to suddenly become comfortable with things in continual transformation.

SCOTT Your work has this incredible ability to remind us that we are spiritual beings having a human experience. And congratulations on the US Pavilion. I was just so over the moon when the news broke. I was also excited to see the commissioners were Kathleen Ash-Milby, Louis Grachos, and Abigail Winograd. Can you share a little bit more about your history of working with these three individuals, and can you touch on the work you’ll be presenting at the US Pavilion?

GIBSON Kathleen, I've known the longest. We met in 2002. She was the very first to visit my studio in New York City. At the time, she was the director of the American Indian Community House in New York City when they were on Broadway. This was the time of slides and it would cost a fortune to get your slides duplicated. But I sent out like twenty packets, and she was the only person who replied. Then, she went to the National Museum of the American Indian, and in 2007, they did a project where they supported young Indigenous artists to come to Venice. So, I went over to support artist Edgar Heap Of Birds. Kathleen and I talked and I remember her saying, “One day we're gonna do this.” So, we've continued this dialogue now for over twenty years. Abigail and I met a few years ago through the MacArthur Foundation and we did an exhibition together. Lewis, I met when he was at the Palm Springs Art Museum. He commissioned a film called To Feel Myself Beloved on the Earth. Then, when he went to Site Santa Fe, we started talking about the exhibition, The Body Electric. And one day, he was like, “You know, we should talk about proposing you for Venice.” I felt like having two curators is important. One, because I need these brains that understand the history of Native American art and everything that comes with that, which is policy, community relationships, and understanding sensitivities. Louis, I just really enjoyed working with and I needed the contemporary art mind. He's very charismatic. So, we asked him if he would come on board to help guide fundraising support for the project. It has been everything that I envisioned. Wait until you see the pavilion.

SCOTT I’m just so excited. The title of the exhibition is the space in which to place me, which refers to a poem by Layli Long Soldier, a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation. Can you share more about the poem’s influence and reference to the planned multimedia installation and performances?

GIBSON I refer to it as “the project” because there's programming, there's education, and there's the catalog—in addition to the artworks in the exhibition. From the very beginning, I knew that there would be text involved. I had to come to some terms with my relationship to the nationhood of the US, and how I think about my biography in the context of the United States. There are lots of obvious things, but where do I wanna sit? The founding documents of the United States were my starting point. Eventually, that led me to the proposed amendments that have not passed. It led me to voices, music, abolitionist speeches, suffragette speeches. I was like, wow, okay, so there have always been these voices demanding some of the things that we're still seeking today in terms of equity and justice. It was important to me to also think about who is represented in the voices that I'm choosing. Of course, I wanted there to be Indigenous voices, Black-American voices, and female voices. And just like when I do an artwork, the title always comes at the end. The pavilion—we're not calling it a site-specific installation; I am referring to it as a site-responsive installation because we took the architecture into consideration. And I’ve had a Layli Long Soldier obsession for a few years. She is able to write things that I didn't know other people saw too. It almost feels like we share a similar experience because of who we are in this world.

SCOTT In your essay for An Indigenous Present, you describe your approach to expanding the way people think about Indigeneity. Has the process of curating such an incredible group of artists and such a monumental publication changed your approach to the US Pavilion?

GIBSON The idea for the book had been with me for a very long time. And weirdly, when I started working on the book, these feelings of resentment were coming up. I thought, why do I have to make this book? I felt like I was waiting for somebody to make this book, and waiting is your biggest enemy. And then, I realized that I was supposed to be the one to make this book. There's been such a moment of recognition of Indigenous artists over the last ten years. More than I've ever seen in my entire lifetime. So, I knew that we were contributing to that moment. And when we published it in the way that it was meant to be published, it was perfect timing. You could feel there was a thirst in the world for a book like this. It wasn't just me. Other people recognized that there was a gap. And so, in that sense, it just felt like being part of a larger moment.

SCOTT We all have educators or ancestors of influence who are pivotal in shaping our lives, someone whose hands we can almost feel on our shoulders in our work and practice. It can be powerful to bring their name into spaces with us. Was there an important figure in your life that you’d like to share more about?

GIBSON I would have to say my parents. They live five minutes from here. My parents were born in the ’40s in Mississippi and Oklahoma, and they both went to boarding schools. So, they both grew up with their families having been in communities that were torn apart. They're part of that generation trying to pull themselves back together and stabilize. To go back to some of the earlier themes that I was talking about—things I have been thinking about. These are things that they have not been able to speak of. They may never speak of them, and that's okay. There's this tremendous amount of allowance that you give somebody because you understand how layered a life can be, probably for everybody. One of the best skills that you can teach somebody is to give it some time. Life is unjust, life is inequitable. That is the world we live in. They taught me that in a way where it's like: yes that is true, but it leads you to learn the skills that help you to make the best of a situation, to give yourself space for mental freedom, physical freedom, creative freedom, generosity, and to recognize the abundance of what's in different spaces. When all you can see is scarcity, it just eats at your soul.

SCOTT On a personal level, I think I needed to hear those words too, so thank you. I think it shapes our lived experiences. And those things could be really intertwined in the social practice of creating, it's the doing, and the making, and the message.

GIBSON Being an artist humbles you very quickly. I've seen a lot of people think about art in this extremely privileged way, but you do need something that humbles you. You have to keep it at this really humble level. Something as simple as holding together pigment on a piece of fabric. The simplest technology of putting color on something, using lines and making images, and making letters that become words that we can share.

SCOTT What role do artistic place-making and place-keeping hold in the work you will be presenting in Venice this year?

GIBSON As I'm walking through what the exhibition is going to look like, who's going see it, and who we've invited to activate the performative spaces, it's really made me realize how much content we're generating at the invitation of one Indigenous person to other Indigenous people to come onto a global stage and be themselves. The spotlight of representing the US in the US Pavilion is a unique platform. I just want to take advantage of that. I’ve been thinking about how to photograph the artwork and the installations. These images are going to circulate. I could say there's no photography in here, but this is how we exist today—this is the time to send this all out as far and wide as we can. This growing interest and focus on Indigenous artists—the goal is for it not to be a trend. We are responsible for our longevity. We need it to go beyond Venice, which is what's guiding a lot of the programming and the educational efforts. How do we make the best of what happens in that space and seed everywhere we have access to?

SCOTT In past interviews, you have spoken about museum exhibition posters on your walls as you were growing up as an entrance point into the art world. What do you think a younger self would say about seeing a poster with your work on it for the Venice Biennale?

GIBSON I'll give you a parallel answer to that. I did get a call from somebody who I know and I have a lot of respect for—a creative person who is very much involved in the Indigenous art scene. And they told me what was so great about An Indigenous Present was that their kid who was eleven or twelve years old could just sit down with this massive book, go through the pages, and see how many people they knew. People they would refer to as an auntie or an uncle. Being able to look at those images and learn something about the person who made the work, who also happens to be family, is so much more powerful than a famous person that you don't know. I have always been pretty obsessed with artist biographies because I've always wanted to know what's at the root. How do I become these people I look at? What biographies teach you is that the person you are learning about did everything to have an interesting life and make their best choices, but there are so many factors that are beyond control. So, I hope my artwork survives me. I hope my words survive me. I hope my biography is interesting. My responsibility is to leave the breadcrumbs—to leave a trail.

Everything Gets Lighter: An Interview of Alenka Zupančič

interview by Oliver Kupper

Slovenian philosopher Alenka Zupančič comes from the Ljubljana school of psychoanalysis, which includes, most famously, Slavoj Žižek. Using the theoretical frameworks of Hegel, Marx, Sigmund Freud, and Jacques Lacan, Zupančič and her contemporaries have produced fascinating insights into social, cultural, and political phenomena. She has written about sex, death, ethics, love, and comedy. Her book The Odd One In: On Comedy (2008) is an expansive and integral Lacanian examination of the subversive machinations of comedy and laughter’s short-circuiting powers, which draws elucidations from Aristophanes, to George Bush, to Deleuze, to Borat. For Zupančič, the object of comedy is the name for all that is funny, which begs the question: how the hell can we laugh in a time like this?

OLIVER KUPPER I heard you on a podcast talking about the origins of comedy—that it comes from ancient Dionysian rituals. Can you talk a little bit about this?

ALENKA ZUPANČIČ Well, Lacan used to say that the original fantasy is the fantasy of origins. We should always be careful when speculating about the “origins” of something, particularly about what this origin is supposed to mean or explain. That being said, yes, there seems to be an agreement among scholars, based on the Aristotelian account, that comedy started with Dionysian rituals called “phallic songs” (also referred to as “penis parades”). This doesn’t tell us so much about comedy as about the so-called “phallic reference” that is central to comedy. Before we jump up and dismiss comedy because of its “phallocentrism,” we better see exactly what this means.

Just think for a moment about the depicted scene: people marching in procession, carrying a phallus of huge proportions made of animal skins, singing obscene songs, full of ambiguous innuendo. Now, ask yourself this question: what is ambiguous innuendo doing in this setting if, at the same time, we have there no less than the phallus itself, in person, and fully blown? If one cares to think about it, it is indeed a bit strange. Usually, we have either the thing itself or the allusion to it. But here it seems that we have both at the same time and the same level. What does the fact that the two appear on the same level tell us? The first conclusion that imposes itself is that the phallus is just another allusion, innuendo. Yet we must be more precise: phallus is not just another allusion, it is the allusion par excellence, the mother of all allusions, so to say. It is the innuendo par excellence. More precisely, it is a signifier of allusion, or allusion as a signifier. This is precisely the Lacanian definition of the phallus. It is a “signifier without the signified,” an “empty signifier,” and as such, the “signifier of signification as such.” The play on signification, its instability, reversal, as well as its surprising material effects are indeed central to comedy.

KUPPER Through the lens of Lacanian psychoanalysis and your philosophical examinations of comedy, what is your interpretation of levity, humor, and laughter in these particularly dark, unfunny times?

ZUPANČIČ As you said, levity can mean many things, and it is impossible to answer this in a general way. So, I’ll try to say something about the specific “levity” of comedy as I understand it. The weightlessness of comedy is often associated with its being without substance. I’d rather say that its substance is very delicate. It’s a kind of soufflé, in contrast to something like pudding. It is a substance shot through with air, and yet, it still demonstrates a consistency, a structure. This demands both wit and skill, or technique, including timing. This is why bad comedy is like a fallen, collapsed soufflé. In this sense, the art of comedy is that of introducing levity into some solid structure, of drilling into it as many holes as possible, without letting this structure collapse. I’m not saying that comedy doesn’t have the power to bring structures down, yet this is more its possible after-effect. Comedy is usually associated with entertainment, and we should perhaps take this word at its etymology (from old French entretenir). That is to say not simply referring to something funny, but to something that holds (tenir) things together in their interval (entre), with the help of the space between them, across this space, rather than by gluing them together.

Concerning the zeitgeist of doom and our dark, unfunny times: This has never been a problem for comedy, on the contrary, comedy often thrives in dark times. The problem is not doom, but its affective solidification, and the morbid pleasure that this solidification seems to offer. Affective solidification of doom squeezes out all space for thought. Because thought operates in the holes of structures. Comedy can introduce the space for thought and the time to pursue it. Thinking, even the most serious thinking, implies a kind of levity. Otherwise, it gets buried under the weight of things before it even starts.

KUPPER In your lecture, The End Of Laughter, you explore comedy through the context of the Hollywood system and how different comedic directors address the ultimate question: is it an artist’s responsibility to respond to the times they are living in? Can you talk about this responsibility and comedy’s place in this reflection?

ZUPANČIČ Shakespeare is the author of the famous line that says art holds the mirror up to nature. The only way one can agree with this is to add that this mirror is a very peculiar one; not such that it reflects reality, but such that it also brings to light the hidden presuppositions of this reality, as well as things that this reality represses in order to appear consistent. The picture we see in this mirror is thus never the same as what we see when we look at reality. It is always somewhat “distorted.” Yet it is precisely this distortion that brings out some truth of reality. This is why to illustrate his thesis that “truth has the structure of fiction,” Jacques Lacan also comes up with the example from Shakespeare, the example in the context of which the famous line about art mirroring reality is pronounced: namely the mousetrap, or play within the play in Hamlet. Fiction can render a reality that a simple mirror misses, yet which is essential for the given reality. Truth needs fiction to register in reality. I suppose that in one way or another, artists always respond to the times they live in. This is part of the artistic sensibility. It’s kind of inevitable—perhaps especially inevitable in what we call “timeless” art. Timeless does not mean something that remains the same across different times, it rather suggests that there is something about this or that particular work of art that keeps changing with time and with different configurations, which rings new and different in different configurations—a reality which is not directly visible, and gets articulated in different configurations in different times…

The more specific question today, to which I guess you refer, is the question of the so-called engaged art: Should artists engage directly in social and political struggles? Again, the answer is not simple, because sometimes engaged art does little else than consolidate the ruling ideology, whereas art that pretends to be there just for people’s pleasure, and stays away from direct engagement, sometimes subverts the hegemonic ideology, since it doesn’t fit or respond to any ideological demand, including that of being appropriately “critical.” The two examples that I discuss in the lecture you refer to are examples of this. I discuss the “political” difference between Preston Sturges and Frank Capra. They both made movies in the times of the Great Depression and the related social hardship, and they both reflected on the position of the film as popular art in relation to that hardship. I cannot reproduce my analysis here. Let’s just say that when it comes to social issues and hardship, Capra leans toward sentimentality, whereas Sturges manages to preserve the levity, and with it the true political edge of his comedy.

My point is not that Sturges is better because he opts for art that is not directly engaged, whereas Capra advocates engagement. My point is that in the end, Sturges’s films—at least some—are much more political and radical. Capra’s slogan is “poor is good.” Poor people are rough at the edges, but they have a golden heart, and we should like, accept, and reward them for that. Sturges offers another axiom: “Poor is bad.” There is very little good that comes from poverty, so it makes no sense to romanticize the poor on account of their inner richness. This is pure ideology. Poverty is like a plague. It corrupts you, rather than makes you noble. It should be eradicated, not romanticized. I thus argue that Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941) is politically much more interesting and subversive than, say, Capra’s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936).

KUPPER You wrote a book called The Odd One In: On Comedy—who is the odd one, and more importantly, why should we let the odd one in?

ZUPANČIČ Generally, we construct our world and make it viable by excluding and repressing some things from it. If something thus excluded (or perhaps repressed) reenters our world, we usually experience anxiety and disorientation, sometimes we even feel that our world is falling apart. Comedy usually finds a way of bringing the odd one in so that we don’t experience this as immediately threatening, but rather as “funny.” By bringing the odd one in, comedy allows us some time and space to entertain the idea or possibility of this foreign element being part of our world, without our world collapsing, or without us reaching full blown anxiety. It brings it in as a possible source of pleasure even. This does not mean, however, that we necessarily end up accepting everything we are offered to entertain in this way—on the contrary, we may well end up rejecting it again, and sometimes for very good reasons. Letting the odd one in is in this sense an interesting exercise, which shatters our horizons in a strangely pleasurable way, but does not simply follow the normative or moral imperative of “letting the odd one in.” To repeat: despite—hopefully—being entertaining, comedy is not just a pastime, but rather something like a time off for thought, for entertaining odd ideas, configurations, and surprising connections.

KUPPER The book was published in 2008—how have you seen comedy, humor, and the comedic evolve, especially in a post-pandemic world?

ZUPANČIČ Well, this is a huge question, carrying in itself a variety of different questions. Ranging from the issues of political correctness and related self-censorship to willful transgressions of all decency as—supposedly—a matter of courage and “balls.” The two often go in pairs, inciting one another. But comedy is not the opposite of censorship. It is something that uses censorship to create new and different ways of saying, and imagining something. And comedy is certainly not simply about publicly “saying what is on your mind,” this is rather vulgar and lacks imagination, which usually relies for its success on brute—physical or economic—power.

But new things happen and break down the smooth or linear logic, which keeps the two sides of this movement on a kind of autopilot mode and produces completely automatic, predictable reactions. Take the most recent example: the war in Gaza. Many activists of the so-called cancel culture have been themselves “canceled” for expressing their views on the conflict. If Netanyahu continues with his devastating politics and uses the word “antisemitism” to silence any critical take on it, the word will soon lose all its meaning. And yet it shouldn’t! Comedy is also not about “relativizing” everything, but rather about pinning down points and meanings that escape this relativization…

I also noticed this recently: more and more, top politicians act as bad comedians, and top comedians act as good politicians—they make excellent, incisive political points and suggestions. What comedians such as Jon Stewart or Bassem Youssef have done recently is not simply what we call political comedy, but along with their comedy, they say things that make all political sense and which on the other hand are in terrible shortage among official politicians.

KUPPER Slavoj Žižek wrote the foreword, in which he talks about short circuits—what is a short circuit in the context of comedy?

ZUPANČIČ It is similar to how many jokes work: they produce and work with surprising, unexpected, odd connections, yet such that nevertheless make sense, even a lot of sense. A short circuit of this kind not only makes you see the connections that are there, but not visible, it also changes the whole landscape, or perspective, and opens new lines of interrogation. This is the idea, at least. Differently from jokes, however, comedy has a temporality in which these short circuits are not its endpoints, retrospectively changing our perspective on the narrative of the joke, but are rather its inaugurating points. A comic sequence, say, often begins with some kind of unexpected short-circuit, or perhaps we should say with an unexpected occurrence, which is then used to create a time and space for its resonation with other elements of a situation, producing other short-circuits along the way. We can also call this comic suspense.

KUPPER You talk about the collective power of comedy. Can you elucidate a little more on this?