interview by Mazzy-Mae Green

photographs by Flo Kohl

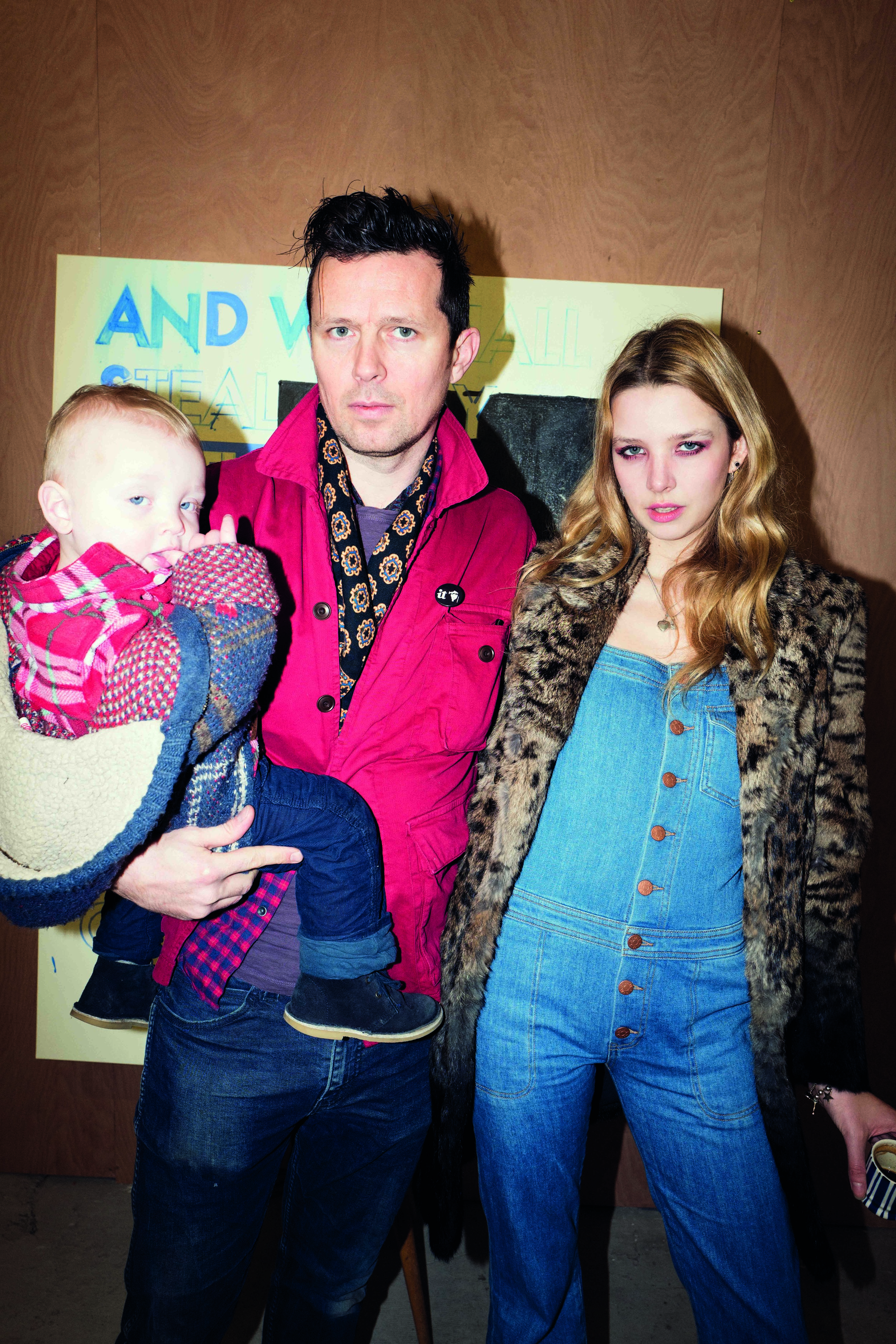

There is something appeasing about the strong political messages that come through in the works of Robert Montgomery, a Scottish artist who deals in text-based pieces, and Greta Bellamacina, a filmmaker, poet, and actor from Hampstead. In a time of political turmoil, both Robert’s three-dimensional works and Greta’s way of interpreting her surroundings, have cemented their place in the contemporary fabric of London, as they lead a new wave of literature and poetry.

Greta and Robert have been composing poetry together since the first day they met and, just over a year and a half ago, started New River Press, a poetry-publishing house in London that bears closer resemblance to an indie record label than it does to a traditional publisher. Although they run New River from their home in bustling Fitzrovia, they also keep a studio space in the more tranquil area of Bermondsey, which Greta describes as a welcome contrast when it comes to musing ideas as it creates equal variation within their work.

We catch up with them in a café just down the road from the studio. As I walk inside, they’re sat around a small table in the corner as Lorca, their child and evident creative influence, totters from edge to edge, seeing if there is enough worth tempting down to his level. I’m told to keep a watchful eye on my coffee.

Mazzy-Mae Green: So, as a question for both of you, maybe Greta you could go first here. Where did your love of poetry come from? Were you around books growing up?

Greta BELLAMACINA: I found poetry quite randomly. I always wrote it before I read it. I started writing from a young age and then only later when I began to study and go to the library did I really start to read poetry. I never called it poetry at the beginning; it just kind of was what it was. But when I first edited a book, I got to read for 6 months to find the best poetry to put into it. It was such an amazing learning curve for me.

Mazzy: How did you come to find it, Rob?

ROBERT MONTGOMERY: I went to a state school in Scotland, but really had a good English teacher. When I was 12 years old, he would bring his own books from home and give them to kids in the class who he thought liked poetry. He’d come up to our desks at the end of class and say, “Hey, Robert and Donna. I think you guys would like these.” So it started with Siegfried Sassoon and the First World War poets, and then he’d bring in Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes and give them to us. And so I read Sylvia Plath when I was 12 and it blew me away.

Mazzy: That’s quite an early introduction to Plath…

Greta: I think I read Sylvia Plath when I was 12. I read the Bell Jar and didn’t understand it. Then I read it again when I was 16 and I was like, “This book is my life.”

Mazzy: There is obviously a lot of value in the written word and preserving the written word – was this sentiment something that you had in mind when you started New River Press?

Greta: Definitely. I think we both found the poetry industry frustrating. There didn’t seem to be any regeneration. There seems to be a lot of reprinting and a lot of safe books. As a young writer, I always found it hard to find a place to publish my work. I found it frustrating. And I think also seeing how many incredible poets we knew who had also faced the same thing. It did seem that we needed to find a way of preserving that language - a language that is so relevant now.

Robert: I mean, I make my living as an artist obviously and I feel as though to get noticed these days you have to really get your own work out there in quite a self-sufficient way. And the poetry world in England is so stuffy. It feels as though the old publishing houses are still run by an almost patrician system. So we wanted to see if we could apply an indie label philosophy to a poetry press. So we looked much more, when we started New River Press, at music labels like Sub Pop than we necessarily did at traditional publishing houses to structure a kind of collective. All the poets get half the money from each book sale.

Greta: Which is really rare. We went on BBC Radio 3, on this show called the Verb. And we were with this other poet and she was saying how she wrote her book for three years, how she was getting it published by one of the biggest poetry publishing houses, and how she was getting paid £400. And we were like, “Oh my god, how are you going to survive? How are we going to preserve the next generation of people coming in, who probably won’t choose to be poets if they can’t afford to be?”

Robert: And I don’t believe the myth that poets shouldn’t get paid. If you sustain this system where poets don’t get paid properly, you’ll end up with only posh wankers being poets and we want to be carving a new path for serious books and finding ways to fund that self-sufficiently.

Mazzy: To come back to this indie pop label approach to poetry publishing, do you think that it is working, or do people still need convincing?

Greta: I mean, I’ve been really surprised. I read a statistic the other day saying how poetry sales have risen for the first time in...god knows how many years. We are living in a time of political worry and there’s negative press everywhere. I think that people look to poetry as an almost democratic voice, a sort of easy, automatic voice of its time. With New River Press we’ve done no traditional press. It’s all been on Instagram or online. The amount of people that have engaged with it online and been like, “I want to find out more about it, where can I find out more about the readings and the writers”. I edited this collection of all-female poets called Smear, as a feminist collection, and we completely sold out within the first month. So it does show that there is this very real element of engagement. What do you think?

Robert: Yeah, I mean, I think poetry is an antidote to materialist language. I think that the language of capitalism and news media in the world is so incredibly harsh at the moment that poetry is the necessary retreat into a more spiritual place.

Mazzy: It’s interesting that there is a growing poetry readership because, in the same way that painting is often associated with old museums and stuffy art, poetry houses are often associated with stodgy and traditional literature. Do you think, then, that there is a new wave of contemporary writing happening at the moment?

Greta: I do! I think we are living in this time where we have a free platform for anyone to write. I don’t think it matters whether that is good or bad. What matters is just that this freedom is given, this freedom to choose, for people to decide for themselves. So you don’t necessarily need to rely on a publisher. You can self-publish your work. It’s a really pioneering time for writers.

Robert: Also we felt that when we started New River, a year and a half ago, that traditional poetry houses were afraid of political writing. For example, Heathcote Williams, who we’re publishing, is really the grandee of British, political, anti-establishment, left wing poetry. He didn’t have a publisher, even though he’s one of the most important poets from the 70s and 80s. That speaks for itself. So we felt with New River that we were carving out a face for political poetry, too. We didn’t know at that point that things were going to go to shit as much as they have over the past two years, so that’s now even more necessary: poetry that’s politically engaged, that is part of the movement for positive social change.

Greta: Like everything in the art world, it has to reflect the time you live in. It has to challenge the time you live in. I think that poetry is one of the most automatic ways to do that. When I edited Smear, I was really amazed by how honest the poets were in talking about abortion, body image, marriage and motherhood. I don’t think these things would necessarily be the first things people would expect to read when picking up a poetry book.

Robert: I think there’s a dawning realization in the art world that there has been this lazy disengagement with politics over the last 20 years that has partly helped lead us to where we are and I think artists and poets now see, more than ever, a need to reengage with politics - and I think we are going to see this intensify over the next 4 years.

Mazzy: Greta, how do you feel motherhood has affected your poetry and Robert your practice as an artist?

Robert: Lorca come back over here...

Greta: I feel incredibly refreshed by it. I wrote a lot of poetry about the internal feeling of being pregnant. I feel like no one ever really writes about the emotive side of being pregnant. There’s so much prescriptive writing; you must eat this, you must drink that, you must do this. I’m quite an emotional person anyway, but I didn’t realize I was capable of delving into even more emotion. You feel so connected to other women. I think that’s been really enlightening.

Robert: We kind of share it. We share those mothering duties.

Greta: We do. I wrote a poem at Shakespeare & Co. You were there. It has this line in it that says ‘we are two mothers.’

Robert: Yeah, I mean, I don’t know if it’s changed my practice as an artist. It’s changed my life. It’s made me feel happier and part of a new family, like I’m in this bubble of love. I lost my own father a year and a half ago and I was really close with him. Being a dad is really good therapy on that front because I see little bits of my dad in Lorca.

Greta: And also I think it makes you think about time a lot more. You see yourself on this strange string and you’re like, “I’m there at the moment, and he’s there.” So it does make you feel sort of semi-more connected to the world, but also sort of connected to death as well, which is quite amazing.

Robert: Ah the fragile thread of mortality. (Comedic voice) We are just barely holding on to the fragile thread of mortality.

Mazzy: And so you guys live in Fitzrovia, right?

Greta: We do, in a matchbox flat right under the BT tower.

Mazzy: And do you then see London as a fertile ground for creativity?

Greta: I do because I think it’s incredibly diverse. We have a lot of friends that live in very non-conventional ways. Having traveled around a lot, for me, London is that one place that really challenges you and it does still have that kind of fresh, young, underground scene. Having said that, just living here is incredibly expensive.

Robert: If they don’t fix the housing crisis in London, then it’s going to be a fucking cultural desert in ten years because all the young artists, all the young musicians and writers will be outta here.

Greta: Yeah, I think the housing crisis is petrifying. I think that it is definitely one of the things that fueled Brexit. Not to say that I agree with Brexit, but I think people’s living conditions were so bad that they wanted to shake things up a bit and be heard.

Mazzy: So in both of your poems there is this recurring theme of the ethereal, of angels, of ghosts. Is this to say that you believe in angels?

GRETA: I love that question! I always love Dreamtime Theory. I feel like the city is a bigger thing. I feel like it’s more of a centralized mind, a centralized heart. So I think the idea of angels for me is the idea that an angel could be a tree, or it could be a person. I think it’s just about having a group voice, a group mind.

Mazzy: So the angel for you is a collective consciousness?

Greta: Yeah, I think so. That’s my take on it.

Robert: Yeah I think cities are ancient, sacred places. All of these shiny new buildings in the sky are built on the graves of our ancestors. So there’s this real sense that they are magically alive places. And I am fascinated by that idea of the collective unconscious. I was always fascinated by surrealist writing on the collective unconscious and André Breton’s idea of the collective unconscious and how it mixes with the romance of the city. I think I was a slightly haunted child.

Greta: I said this to Rob the other day, but I feel like you could almost survive just off sunlight. I love the idea that the plants, the trees, the flowers, the land, that they’re always being renewed by sunlight. And in a way I kind of see that as a symbol of angels. It really is that renewal that makes me feel closely connected to the ethereal.

Mazzy: Robert, when did you first decide to turn your poetry into three-dimensional sculptures?

Robert: I don’t know if I decided that at any point. I mean, I went to art school to study painting and I read poetry passionately in the library. I tried lots and lots of different ways to make painting and writing go together. From the time I was at art school until now I tried lots of ways that failed, and I just kept trying until I’d bashed out a couple of forms that worked. I started working with billboard space, and hacking advertising space in 1994, right back in art school, so I’ve been doing that for a long time.

Mazzy: With the projects you were doing in off limits spaces, did you ever get in any serious trouble?

Robert: Hmm.... I once did an illegal billboard piece in Bethnal Green, actually it was in the lead up to Brexit and it said:

“England is the first lie. England is a lie the invading kings told you to take your actual land from you. This land is your land from the flat Norfolk night to the blue Cornish morning. Just a wild Pagan land with no name and no flag. Just this cold beach that nourishes you/just the wind on this grassland that nourishes you/just the rain on your face in the morning in this blank springtime that nourishes you.”

And for some reason I was doing that billboard and a police van pulled up really fast and five cops got out and they dragged me into the back of the van and...

Greta: He says whilst picking up a baby bottle.

Robert: ...And I was sure I was going to jail. But then one of the four cops in the van, I discovered I could speak to. He was a bit softer. We started talking and I said, “Look, what I’m doing is public poetry. This is really about how the land should belong to everyone, about how the land should belong to you as much as it should belong to the queen.” I always carried this little book of poems with me if I was doing any of these illegal things, and I took out the book and started showing him some of my other poems. We talked about it for about 20 minutes. He had the other police officers let me go.

Mazzy: What an incredibly fortunate time to run into a fan of poetry.

Robert: I just hope as the years go by, more and more police officers will become fans of poetry. I mean, we should start sending them books.

Mazzy: I sense some future billboard plans. Greta, you recently released a film about the decline of British public libraries, and you spoke to a lot of people whilst you were making it. What was that process like?

Greta: It was very DIY. I’ve always been a massive advocate for public libraries. I see them as temples of learning. I know a lot of students who couldn’t afford wifi at home. They went to the library just to get through exams. At the beginning it was meant to be a short call-to-action film. It was almost like a visual essay. So we got Stephen Fry to come in and all these kind of talking heads. John Cooper Clark. Rob was in it. We went to the first ever public library built in Scotland by Scottish miners in 1754. And once we got into the history and started to really research what was going on, I realized quite quickly that it would need to be a feature length film. Just because it was so relevant to what is going on now. There were so many stories, so many campaigns, and so much history attached to every single building. And it felt like to give it justice, it needed to be a longer thing. So it took a year to make and was edited quite quickly and then it launched in cinemas last February. Since that time, the response has been amazing. It’s something that people feel passionately about.

Mazzy: What effect do you think Internet platforms such as Youtube and social media have had on the written word?

Greta: I think it’s helped enormously. I think it breaks the snobbery around the art form. I think it really lets people decide for themselves if they like something or not. I mean, there is that element of, unless you know what you’re searching for, then you might not find the material you want to find, as well as the whole role of subliminal advertising. But I think for artists it’s so refreshing to break away from the traditional output.

Robert: Yeah, for contemporary art, it’s definitely a healthy, democratizing medium. It expands the audience beyond the gallery, which is a really healthy thing. I mean I was very optimistic about the Internet as a force for good until I saw how insidiously Facebook was used to manufacture consent for Trump. It’s really making me rethink how positive I think the Internet is as a whole.

Mazzy: What are you guys working on at the moment?

Robert: I just got short-listed for the National Holocaust Memorial, which is the permanent memorial to the holocaust that will be built on this side of the Houses of Parliament. So I’ve just finished that and submitted it. I’m also currently doing some paintings in the studio, which is something I haven’t done for a while - so I’m really enjoying that. I’m going to do an exhibition in May in Mexico of some anti-Trump declarations in Spanish.

Greta: I’m currently making my first fiction feature film, Hurt by Paradise, which is this kind of conversation about how society has these rules and ways and if you don’t fit within them then you are an outcast.

Robert: I’m excited about your film!

Greta: I’m really excited. I’m just finishing the first draft of the script, so I’m hoping to film by this summer. I’m just busy roping in lots of people at the moment. And we’re getting married!

Mazzy: Oh wow, congratulations!

Greta: We’re really excited. We’re doing it as more of a festival of art and love. We’re not doing any of the traditional stuff. We hate traditions. We’re making our own traditions. We’re not going to have a priest. We’re going to make up our own vows and just say them to each other.

Mazzy: I just had one last question. It’s not something I’d planned to ask, but I’m suddenly interested in what you might say. Do you have a favorite poem?

Greta: Oh, I do. My favorite poem is Love Song, by Ted Hughes.

Robert: So many Lives, by John Ashbury. So many Lives, by John Ashbury.

Greta: Love Song, by Ted Hughes.

(Laughter)

˚