Cole Sternberg

the official flag of the free republic of california, 2020

Ink and stitched applique nylon

48” x 72”

interview by Michael Slenske

“The nation is an artwork and we the people are the artists.”

-Susanna Dakin

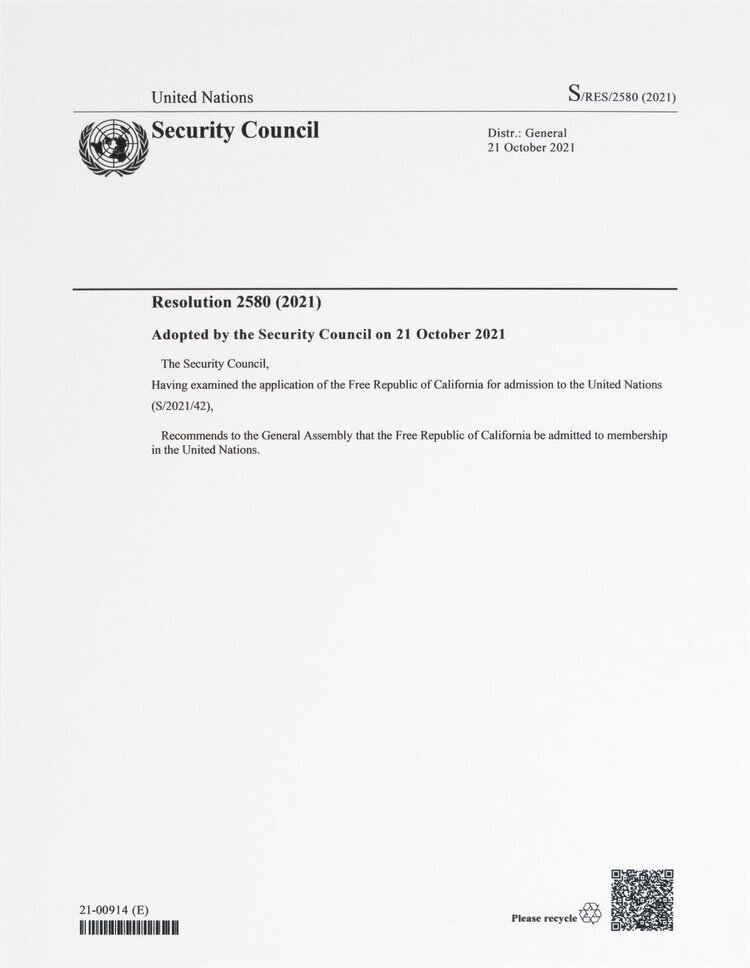

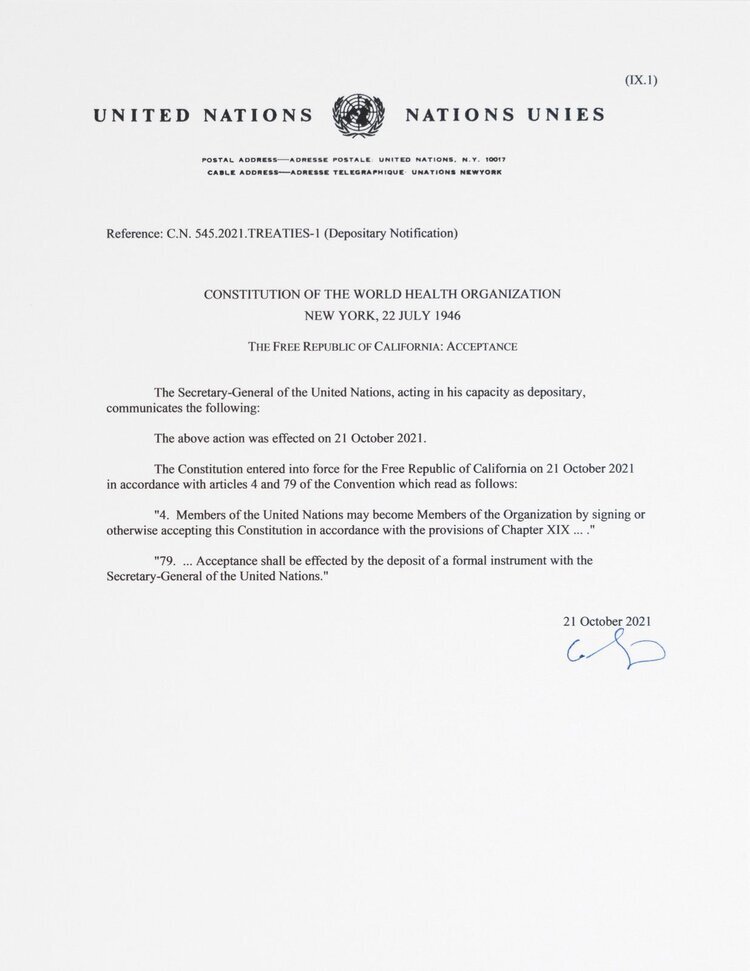

In 1984, artist and social activist Susanna Dakin set out to prove not only that nation building is an art unto itself, but that we as citizens are more compelled to take part in its creation than we might like to think. Almost four decades after Dakin pounded the pavement from coast to coast as a durational performance art piece, artist Cole Sternberg has applied the lessons he learned in law school to a radical reimagining of California statehood in FREESTATE, his agitprop public movement via exhibition at ESMoA. A variation on the traditional idea of secession, his proposal includes an invitation to all nations and all other states within the US to join. And unlike Dakin’s performance, Sternberg does not place himself in the role of a delegate, but rather a draughtsman, or perhaps a professional dreamer. The project is part constitution, part policy and budget reform, part sculptural installation, part digital revolution, and part public education extension in civics, complete with a sleek visual identity and merch game, all scored to the tune of “California Dreamin’” by the Mamas and the Papas.

SLENSKE: So we walk into the exhibition and it starts with the gift shop.

STERNBERG: Normally a museum is one large room. And the curator and I had this idea to break it up into three. It’s a loose, reverse chronology of the origin story of the Free Republic. This first room looks like a store, or maybe it’s a graphic design office, or a sort of minimalist canvasing office. You don’t really know, and people who have been to the museum are like wait, what happened to the museum? And nothing’s for sale, so it’s just a little confusing, which I like.

SLENSKE: So nothing is for sale.

STERNBERG: No.

SLENSKE: But there is a shop—you can buy stuff, but not here.

STERNBERG: Just online. Online exists as its own art piece, really. This is one component of this broader idea of a Free Republic.

SLENSKE: So, this is more like the propaganda room.

STERNBERG: Yes, totally. It’s the propaganda room. Most importantly, it’s meant to engender this idea that something big is about to happen, or is happening. And then on the website, you can download any of this information. The budget’s one of the things that, with coronavirus, got much more dialed in. Originally I thought, I’m going to do a screen print or a painting of a math equation of our new budget surplus, and that’s it. Then the show got postponed, and I was sitting in the studio and I thought, well okay, what could we spend this money on? How much would it really cost for universal healthcare, or higher education for everyone, or for more low-income support, or our own EPA, and all of these different things? And it was shocking to realize how many things we could fit in that budget surplus. And the way we get a budget surplus is we provide all the services that the federal government currently does, but there’s a differential in that money because for every dollar we give the federal government in taxes, we get about 75 cents in so-called services, Kentucky gets $3 for every dollar they spend, so that creates a big surplus. Then, the military budget is so crazy that I thought, do we really need this? If we cut our military budget by three quarters, California would still be in the top fifteen militaries of the world, but that adds another hundred billion annually to our budget, so that pays for everyone to go to public or private higher education of any level, pays for the universal healthcare, pays to over double our low-income support, pays to have an EPA that’s four times as big as the US EPA, and a $60 billion transition fund annually, which would eventually go away once we’ve transitioned. I would like us to not really do that, but to have the number ammo to fight for a more pacifist, less war-mongering existence. It’s about $15-20 billion dollars to pay for the higher education of California. That’s it, and California contributes about $200 billion annually to the US military.

SLENSKE: Tell me about the seal. Why this design scheme?

STERNBERG: The State of California seal is almost the same. Creatively, you want to go more wild, but I wanted it to be confusing and make people think maybe this is real already. I reversed Minerva, the goddess. She’s looking in the other direction. It used to have thirty-one stars, now it only has one. There used to be an unknown building in the Hills that some people think is San Quentin—I don’t think it is, but either way I thought eh, we don’t need it. And then the text. I left “Eureka” because I like the idea of Eureka; it’s not tied to any racism of the first Anglo settlers here. And that’s it. It just exists like that. On the website now, there’s a graphic design high school class that all made their own seals. They could make it all about equality, or all about sustainability—the specific issues of the show.

SLENSKE: There’s kind of this theosophist bent. Have you seen Can’t Get You Out of My Head, that new Adam Curtis documentary? It’s this idea of how, in the last hundred years, any sort of meaningful society has caved under the pressure of capitalism from Mao Zedong, to Putin. So, I think of that and I think: are there any more possibilities right now or no possibilities? What do you think?

STERNBERG: There are possibilities. My aspiration for this is just a little bit of movement in the right direction, you can’t have everyone suffering and have it not crumble, and capitalism seems to just lead back to feudalism. So, it has to go in a different direction. This is the only real document in this room. I mean real like, that is fabricated, that is California joining the Paris agreement, and I really geeked out on these types of documents. Like, if everything happened, they would look like that. I went to the first impeachment hearing, and that was my ticket. I didn’t want to comment about Trump because this isn’t about Trump; it’s about these systemic American issues that we’ve never addressed, or solved, or anything, but I did want to touch a little on that, and impeachment is treated totally differently in my Constitution.

SLENSKE: What’s the difference?

STERNBERG: There’s a High Board of Impeachment which is run by a non-partisan body, and the Attorney General plays a big role in it, but the Attorney General is an elected position and not an appointed one. So, I pulled part of the presidential cabinet away from the control of the President because I didn’t see why the head of the EPA should be chosen by the President. I don’t think the President should have that much power, so I pulled a few things back, one being the Department of Justice, and another the EPA and another the State Department.

SLENSKE: You’ve done a lot of different types of experiential work, from dealing with your grandmother’s TV den, to being on this maiden voyage from China to Portland—why do this? Was this in the back of your mind for a while?

COLE STERNBERG: Well, whenever McCain named Palin his running mate, I was living in Budapest with no painting studio. I was mainly painting at the time, and I just thought, America’s really annoying me at the moment. I’m going to write this book about California having a coup d’état. So, it was a stream-of-consciousness thing. It was 350 pages, and then I didn’t read it. I didn’t go back and edit any of it, I just kept writing. I got home here, and read the first ten pages and I was like, god this is horrible, and I put it in a drawer. Then, cut to about two and a half years ago, the curator of this museum who is a good friend, came over and we went through a list of my ideas that had been floating around, and this was one of them. He said, you should pursue that one in this era of the crumbling of democracy. Cut to now—it’s developed into this huge thing where it’s not really about secession. The secession is just a guise to get people to listen to the ideas, really. I went to law school, and I’ve used that knowledge and anger about certain things in the works in certain ways, but I’ve never directly used that in this show. In terms of writing the Constitution, I said, “Oh, I can use what I studied and now I’ll have the confidence to at least draft documents in a way where I know they’re pretty close to the correct thing.”

SLENSKE: Did you have practicing lawyers go over them?

STERNBERG: Well, I did with the Constitution. I technically had three lawyers. Two just to review it, and another reviewed the Spanish translation, and a dear friend of mine is a Catholic priest who went to the London School of Economics and has four graduate degrees from Cambridge. He’s this super smart, thoughtful person, so I had him review it, too. His was actually the only substantial change.

SLENSKE: What was that?

STERNBERG: He said, “You should consider adding a public bank, and I didn’t realize this. I knew check cashing organizations are a huge rip-off, but I didn’t know the depth of not having access to banks through our society. North Dakota is the only state with a public bank, ironically for their anti-socialism views, and it’s been around for 90 years, and they love it. The access to a public bank is great ‘cause there’s no drive for profit of that bank, so in the Constitution I added that we’ll have a public bank, when you’re born or become a resident or a citizen, you get an account, you can cancel that account if you want, and if you’re born here you get a savings bond for an amount determined by Congress, and that’ll mature until you’re eighteen, so it gives you access to the banking system that a lot of low-income places don’t have, or have at such a high premium that it’s inaccessible. That was his main change. The lawyers corrected a few typos. They couldn’t find any critical things.

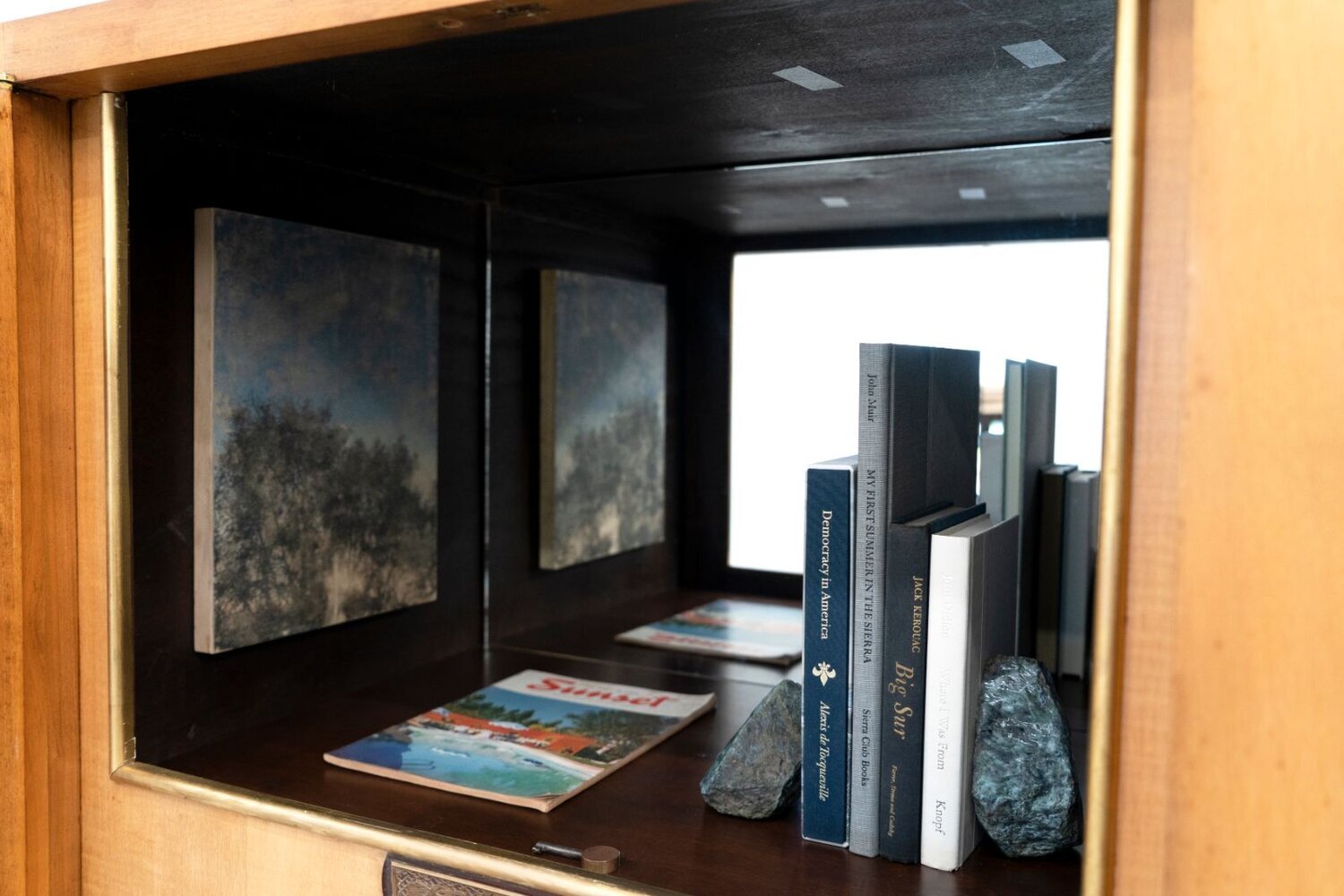

SLENSKE: What’s going on over here with this record player console thing?

STERNBERG: This is the audio centerpiece of the whole show. I wanted to add a couple of sculptural components in general.There’s a bibliography on the website of about sixty books. This one I picked–well, de Tocqueville is obvious, and he mentions everything we’re talking about today. He’s like, “this attempt at democracy is interesting, but I’m not sure if it’ll work given the structure of voting and that it’s founded in slavery.” And then, Joan Didion, her family were some of the first settlers to Sacramento from the East Coast, and she tells about that journey to Hollywood. So, that was sort of a romantic and dark view of California. John Muir’s My First Summer in the Sierra was his first book about California.

SLENSKE: So, they’re almost like foundational texts to what California is in the mind of folks?

STERNBERG: Totally. And a little bit of nation building, and a little bit of insanity, because Kerouac’s Big Sur doesn’t help with the story of California very much, but in the end, he’s standing on the beach in Big Sur, which is arguably the most beautiful place in California, or the world, speaking gibberish because he’s gone nuts. So, that’s just kind of a joke of mine about me and this whole idea. And then, these are Serpentine rocks, which are the official rock of California.

SLENSKE: There’s all these fictional documents, it’s a construct itself, even though any Constitution is the same way. You made it before this moment, too, but it feels like it was made in this moment.

STERNBERG: That’s the crazy part. It actually makes me feel so proud of certain things like the Constitution, because I was trying to draft something that would be an infrastructure, and then current events come and crash into it, and hopefully it resolves those things properly. I’ve always been doing things simultaneously, and I’ve always been writing. Two years ago, I wrote a letter to Gerhard Richter every day and mailed it to him.

SLENSKE: What happened to that?

STERNBERG: I made three copies of each letter, so I have two copies, and I know it’s the right address for him, they all went to him, he never responded. I created a bunch of rules for myself, too. I never mentioned his art, or my art, geographic location, rarely a proper name. It’s like you jump into the middle of a real friendship when you read it. I think I just make all of this stuff anyway, format-wise, and this just dramatically highlights that part of the practice.

SLENSKE: That’s amazing. How long did that go on for?

STERNBERG: It was a year. Every day.

SLENSKE: What year?

STERNBERG: Oh, 2017. I picked a lot of generic things, so January first it started, December thirty-first it ended. I made letterhead that was foiled and embossed with my name and everything, but then so was his name and address, and the same with the envelopes, so they could only serve one purpose: to go to him. But very generic looking, not like an artist’s letterhead. I had a portable printer that I carried in my backpack, and my rule was just that it had to be in the mail before midnight. I think I was in seven countries and fifteen states or something during that [project], and for two weeks I was in Berlin, which I just thought was funny because he might be like, oh shit, this guy’s getting close based on these stamps.

I picked Gerhard intentionally, thinking he’ll never write back, I like him as an artist, I know he’s a grumpy old man—like, if I wrote to Jasper Johns, he’s a friendlier guy. At some point someone would have written something back. So it got more and more freeing, too. It was more of a diary; I didn’t care.

SLENSKE: Do you feel like this project here is trying harder to find a response, in a way?

STERNBERG: It does feel like I’m yelling into a tunnel, whereas before, with Gerhard, it was more just talking in a tunnel. I wouldn’t care if the Gerhard letters got out now that I’m done with them. During the process, I don’t know if I would’ve wanted them out.

Cole Sternberg

structural assistance, 2020

Ink on paper

13” x 19”

SLENSKE: What’s this? Is this the LA Times?

STERNBERG: Yeah, that was in 1910. The LA Times was bombed. There’s three painted things like this in here where I’m starting to fix damage, but they all deal with multiple issues at once. This one, you think oh, okay, it’s against violence and terrorism and for free speech, but also the bombing was by two union members who were mad that the publisher was anti-union, and that allowed the anti-union movement in California to really push toward not having unions. We have less unions even than other states in America, and this is one of the big marketing things they were able to do to accomplish that, which is a huge bummer.

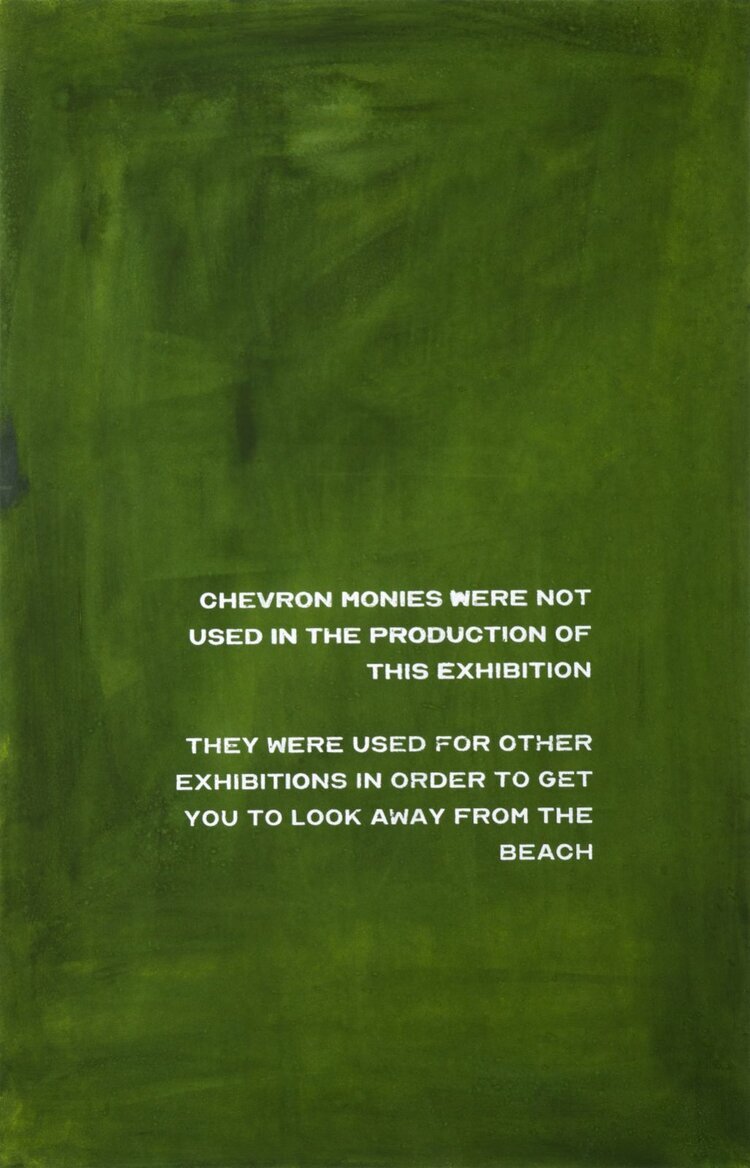

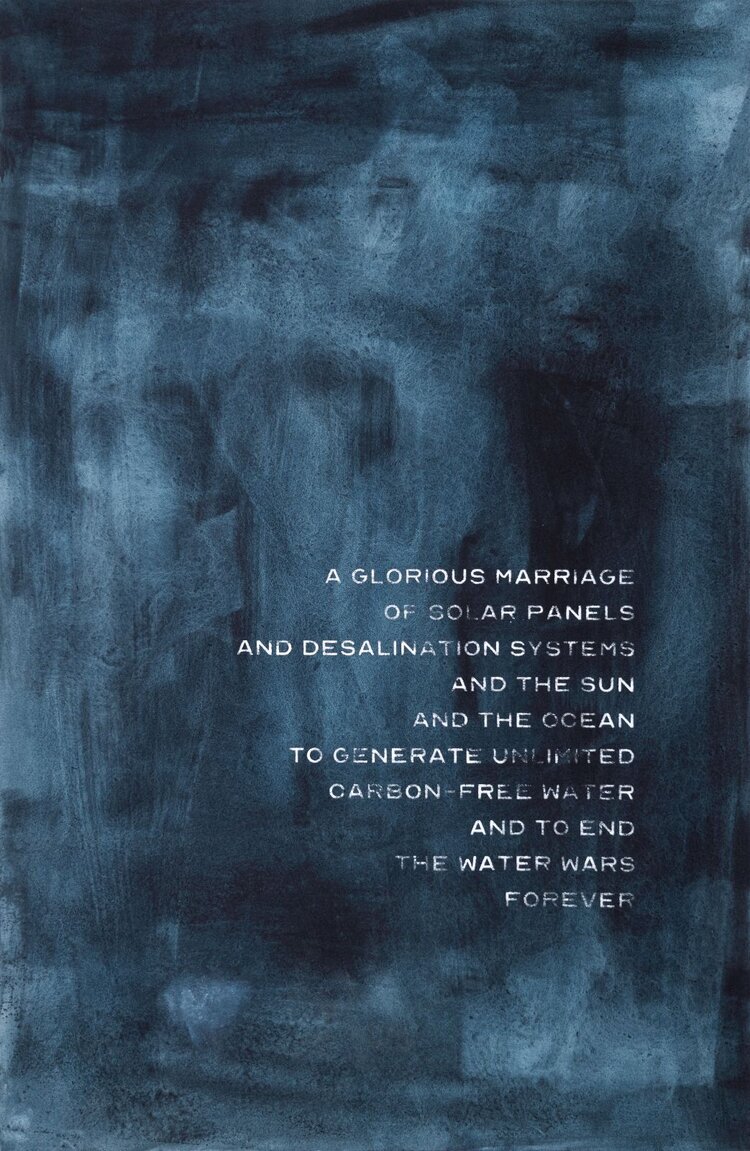

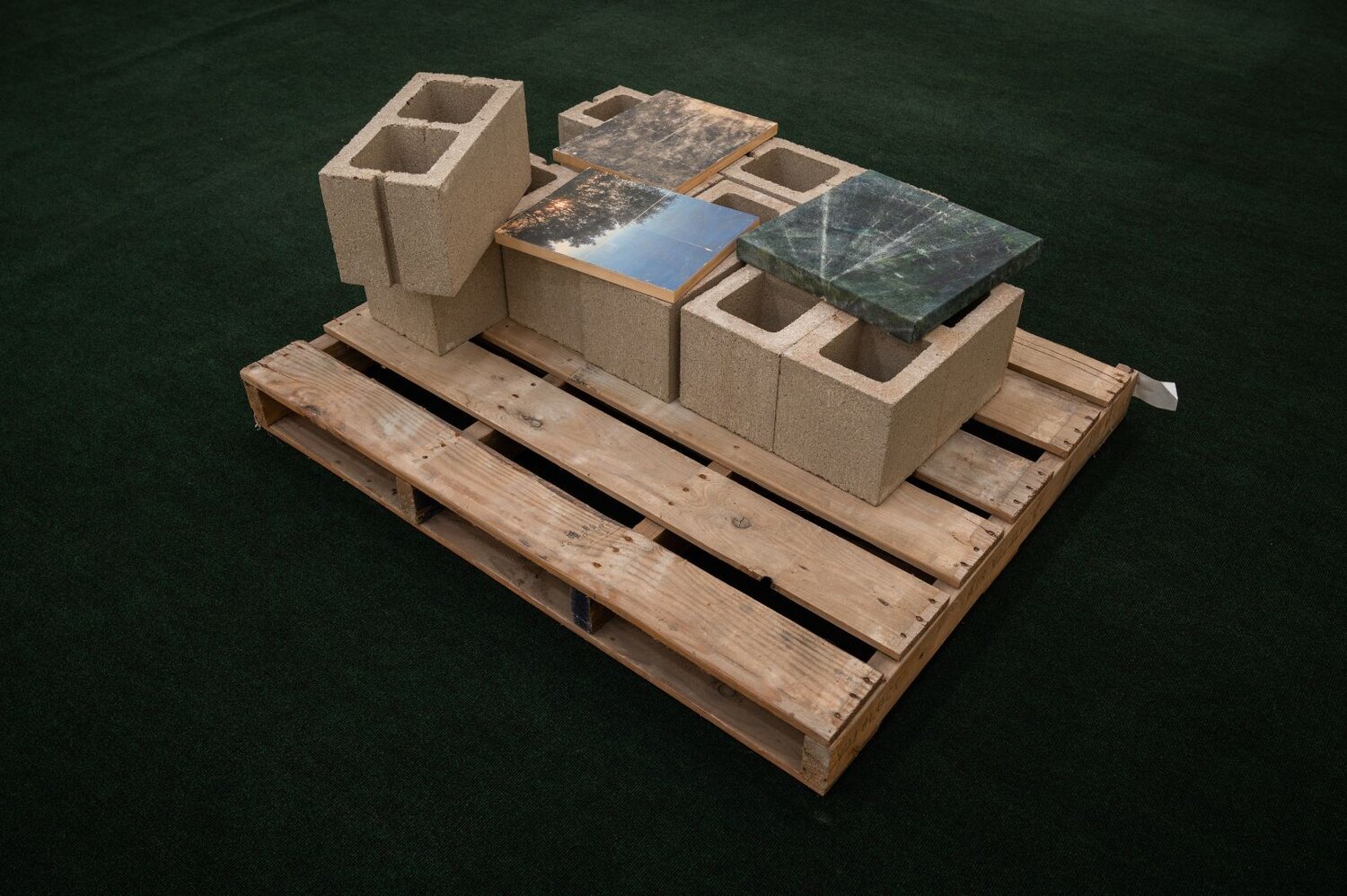

SLENSKE: Then, what’re these paintings?

STERNBERG: These all work together. These are paintings and screen printing together. You know the water wars are a big thing in California, and with how we’re going to be sustainable, we have to treat water differently than just wasting it all the time. The main reason desalination systems haven’t worked historically is the energy was too expensive to justify doing it, but we’re close to the point where batteries can store solar and wind at a large enough level where theoretically, you put all the solar panels in Death Valley, store it somewhere from there to give to Santa Barbara, take the water in and desalinate it closer to Santa Barbara, so it’s something where we’re really close to that technology.

SLENSKE: So, what’s going on in this last room?

STERNBERG: This is more of the beginning. It’s more like a traditional museum or gallery. You can breathe a little easier in here. So, it’s more grandiose thoughts of freedom and escape. It’s also a kind of strange assortment of things. This feels like a very Anglo-American, faux tough-guy, property rights-driven kind of a thing. It’s a gate from a barn, like a ranch. It’s on a little bit of a slant because it was on a road with a slant, and it’s decaying. This gate is easier to move, it’s already being torn apart, so it’s a similar feeling in a way but maybe more motivational because it’s so easy to get around it.

SLENSKE: It also seems like it’s been breached.

STERNBERG: Yeah. This is a piece of a California live oak. I was trying to save the live oak, but it looked like a peace symbol and a slingshot to me. I liked that there were still worms eating away at it. It’s kind of an homage to Pierre Huyghe.

SLENSKE: And then, this is the Turner-esque moment. Are we going out into the sublime or not?

STERNBERG: Exactly, and that’s funny. No one said Turner yet, but I also have never really used this rich of an orange. It feels really Turner-esque in that color palette. Yeah, it’s more romantic.

SLENSKE: Explain the flag real quick.

STERNBERG: I’m not a huge flag person, I don’t care how they’re designed necessarily, but I thought well, we need a flag to highlight how big the dream is. Baby blue is more like peace and the UN and diplomacy, green is the environment, and a darker blue feels to me like the Pacific. The original flag of Mexican California was just a red star in the middle. I like not changing the seal completely. I like that one sort of shoutout. I used to love the verified flag—our California state flag—but the people who designed it weren’t the best people. I didn’t think there was a point in continuing it.

SLENSKE: So basically, the end and the beginning are in this room.

STERNBERG: Yes. We thought about reversing the whole order, but it felt more interesting this way.

SLENSKE: Well, in a certain sense, to start a revolution, you need the marketing. Then, this is the documentation and the meat, and back here it’s sort of, where do we go next?

STERNBERG: Kind of a reward. This is the nicest feeling room.

SLENSKE: Do you want to present this to California Congress? Do you want the mayor and the governor to see it? The Attorney General?

STERNBERG: Oh, for sure. I’m going to send Gavin Newsom a letter.

SLENSKE: I’m sure he’d welcome that right about now.

STERNBERG: [laughs] I’m going to send him a nice bound version of the budget and the Constitution, and I started to think California could amend its Constitution. It’s not going to have any federal law effect, but why don’t we just do that, just as a statement? I think that’s what I’d propose first to him. So, not seceding or anything, but hey, we have an old, California Constitution that has many of the exact same flaws as the US one; why don’t we just change it? I feel like people kind of forget about the California Constitution.

SLENSKE: I love this idea of reading the US Constitution and then reading this as a comparative analysis. Going back to big money, with issues like universal healthcare, the approval rating is through the roof, but it never happens. It’s the market that’s always going to fight back against these things.

STERNBERG: Healthcare, for instance. We pay the most of any country per person for healthcare, and we’re forty-sixth in the world in life expectancy. You could spend less money, more money goes into the economy, which then duplicates itself. So, you could talk in the language of capitalism even with people’s lives and healthcare in a way that should motivate them to change. I wrote an official letter to the head of Goldman Sachs a couple months ago. It’s this playful thing, like the Richter letters, but then it says, “You have all these clients. You have portfolios; they’re supposed to be diversified, and they call it a diversification quilt. But if you have a quilt and you take out one patch, you can still stay warm, and the one patch you should take out is natural resources.” The historical reason they wouldn’t is it makes clients money and clients don’t give a fuck, but now it doesn’t make money. It’s the worst performing patch in the quilt the last few years, so I can speak to it in the natural, rational way, but also the monetary way. If you had put that into wind and Tesla, you would’ve quadrupled people’s money. Instead, you lost seventy-five percent of people’s money in that quilt, so maybe we can move on from that to everyone’s benefit. Specifically for him, it’s his fiduciary duty. I’m trying to talk in the words of capitalism because it makes sense for capitalists to make these changes.

SLENSKE: Maybe that’s part of the amendments. Money talks.

STERNBERG: I mean, it does, and it’s just crazy when you think of how no one, Biden or Trump, or whoever—we don’t talk about cutting the military budget. Ever. It goes up every year even if we’re not in a war, or if we just finished a war, it still goes up the next year, and we’re seven times the second largest military, which is China, in spending annually.

SLENSKE: The thing about spending so little on health and education outcomes is that you have to have a big gun if you’re undereducated and sick all the time.

STERNBERG: Totally. It’s a barbarian concept of society.

FREESTATE is on view through September 18 at ESMoA