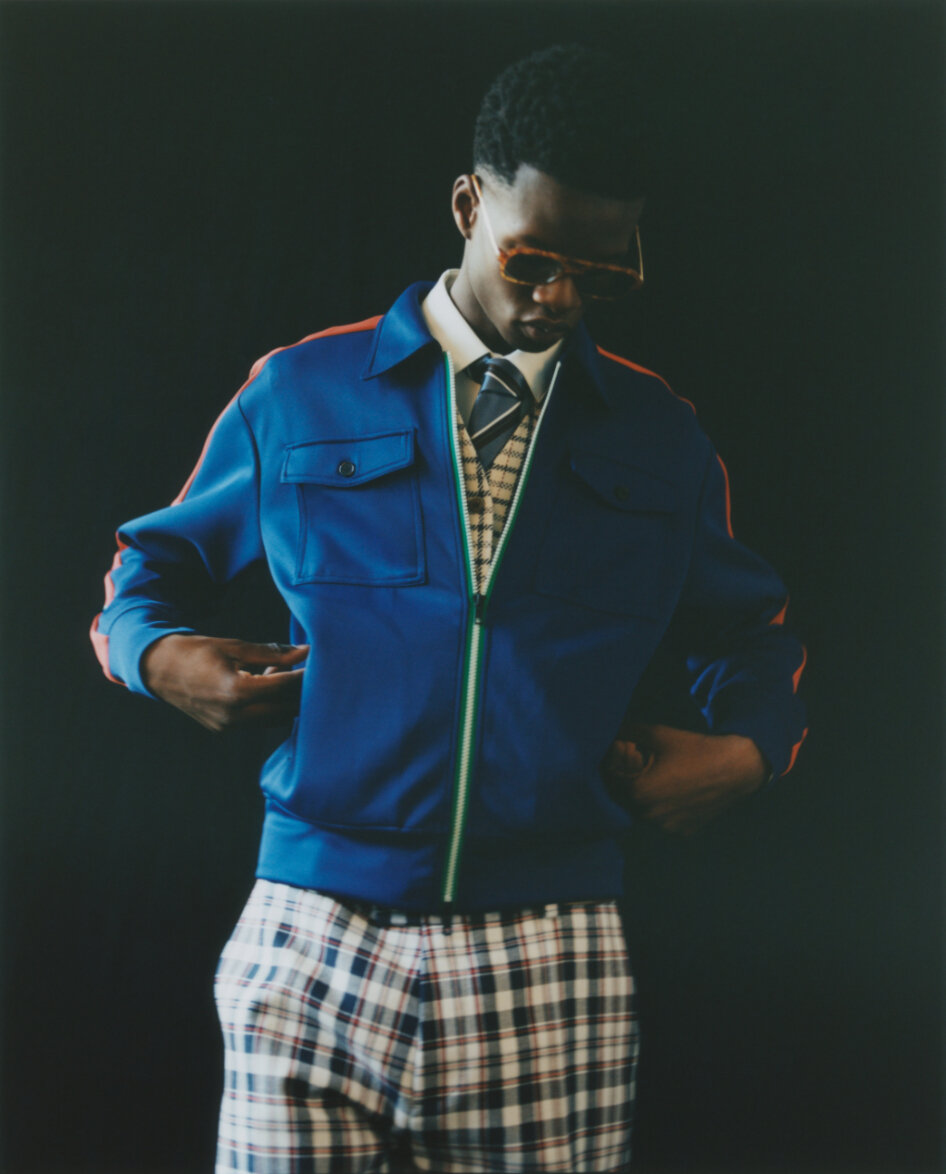

LEFT

suit: Moschino

turtleneck: Versace

scarf: Daily Paper

earring: Alama

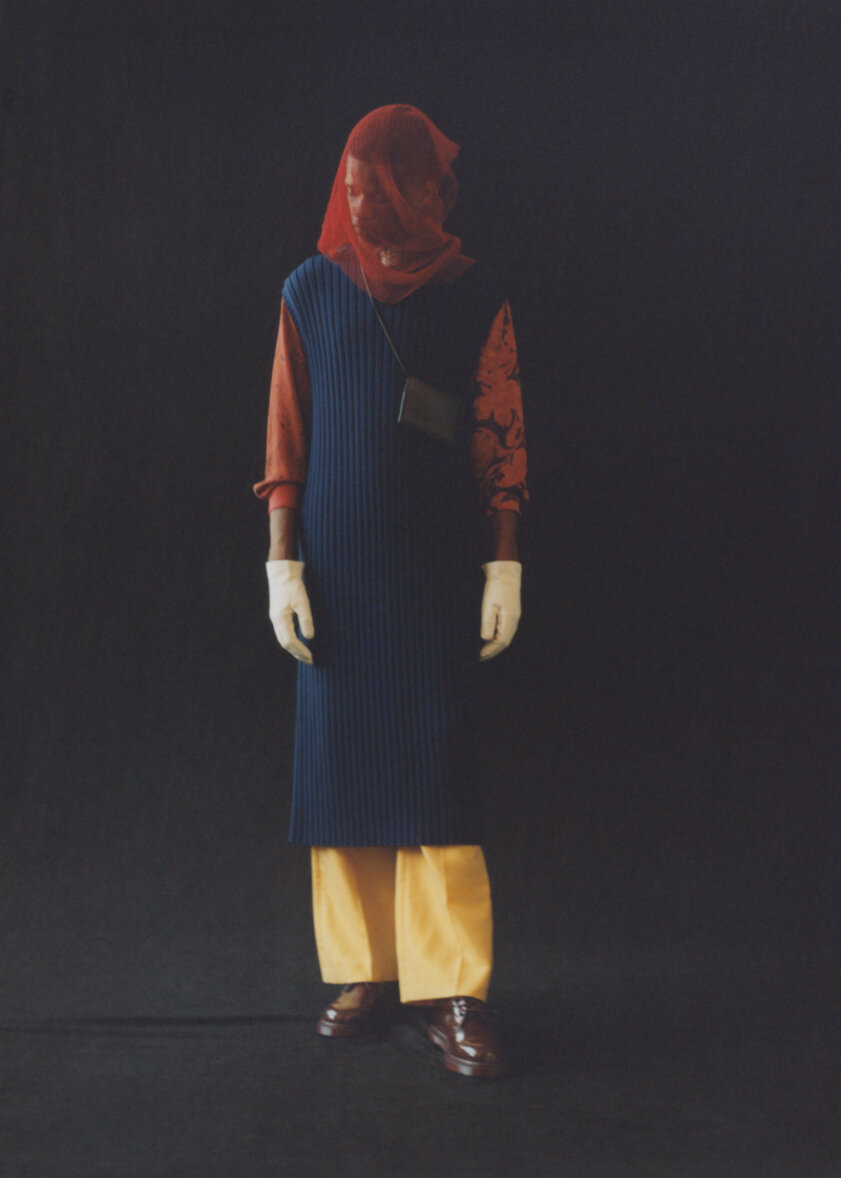

RIGHT

mesh top: Gucci

shirt: Dries van Noten

neckerchief: Falke

photography by Lennart Sydney Kofi

styling by Peninah Amanda @ Liganord Creative Services

art direction & production by Eugenia Vicari

talent by Thiam and Jodeci @ IMG Models Worldwide

hair & makeup by Maria Ehrlich @ Collective Interest

processing by gOLab Berlin

retouching by the hand of god

photography assistance by Mark Philip Simpson

styling assistance by Naomie Mahray

shot @ Welcome Home Studio

with special thanks to Hakan Solak & Maria Ianniello

How did you discover your love of photography?

It didn’t happen from one day to the next. Photography was part of my life from as early as grade school, and when I realized that words in particular, but also music were not the universal language that I was intuitively searching for, I fell in love with photography.

What was it about fashion photography that drew you in?

This happened accidentally. I started studying photography and I dreamed of becoming a reportage photographer, traveling around the world and documenting life, but quite early on I learned that this wouldn’t pay my rent. My university had a lot of fashion students and I started making a business through shooting their collections. It took me some time to make my peace with shooting fashion. My thesis was about how clothing turns into fashion and what happens when you point a camera at it. This is actually a topic that still interests me and it has so many facets like fashion in relation to gender, sexuality, identity, society, and (sub)culture.

blazer: HUGO

shirt: Hérmes

rings: Elhanati

hat: Fiona Bennett

What do you look for when casting models?

To me authenticity is super important. This has to do with finding the “right character” for a certain project or topic. Since my early days in photography, I have been working with people from different subcultures because this is a huge part of my personal background, too. I have always wanted to give the people who are not usually represented in society, and especially not in fashion, a voice. I really appreciate that human diversity has become important in fashion photography, even if I sometimes question whether or not it’s just become a trend rather than a deeper understanding of society and what needs to be changed.

This shoot explores the concept of the African dandy. How would you describe this man and what was the inspiration for this concept?

A dandy by definition is someone who excessively pays attention to his or her physical appearance, in terms of dressing up. A dandy creates fashion, rather than following fashion trends and usually doesn’t pay much attention to secular affairs. This is a concept one would not necessarily expect to find in Africa (from a eurocentric/western point of view), as many people imagine Africa as a rather poor continent where people deal with existential worries. I liked the idea that the people we would often consider “poor” develop an attitude which allows them to free themselves and present in carefree and colorful ways. This is where a rich culture meets creativity and becomes a great way to express through fashion.

Dandyism is also a mindset in terms of not worrying too much about tomorrow, enjoying life and behaving gently. The African Dandy movement is called SAPE which means clothing in French but also stands for (Société Des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes (Society of Tastemakers and Elegant People). It started in Congo, when people brought the concept from France and turned it into something their own.

My background is also half African, so for this story, so many details came together on so many levels. The story is inspired by my intention to question the concept of fashion and an extensive search for my roots.

Has the image of the African dandy changed over time? If so, how?

It has. The movement was mainly carried by guys, in the beginning, now there are more and more females joining, calling themselves sapeuses.

Can you talk a little bit about your collaboration process with stylist Peninah Amanda and what you both were trying to achieve?

Peninah and I knew of each other, as we have some friends in common, but actually never met or worked together before. When I sent her the concept, she really felt the idea and we vibed immediately. She happened to be in Kenya at that time and she managed to bring a lot of props which helped us to densify the entire story. And sure, one goal was to feature African culture within the fashion world.

knit: Lecavalier

shirt: Magliamo

tie: Fumagalli

pants: Karl Lagerfeld x Ize Kenneth

shoes: Dr. Martens

small bag: David Kossi

gloves: Roeckl