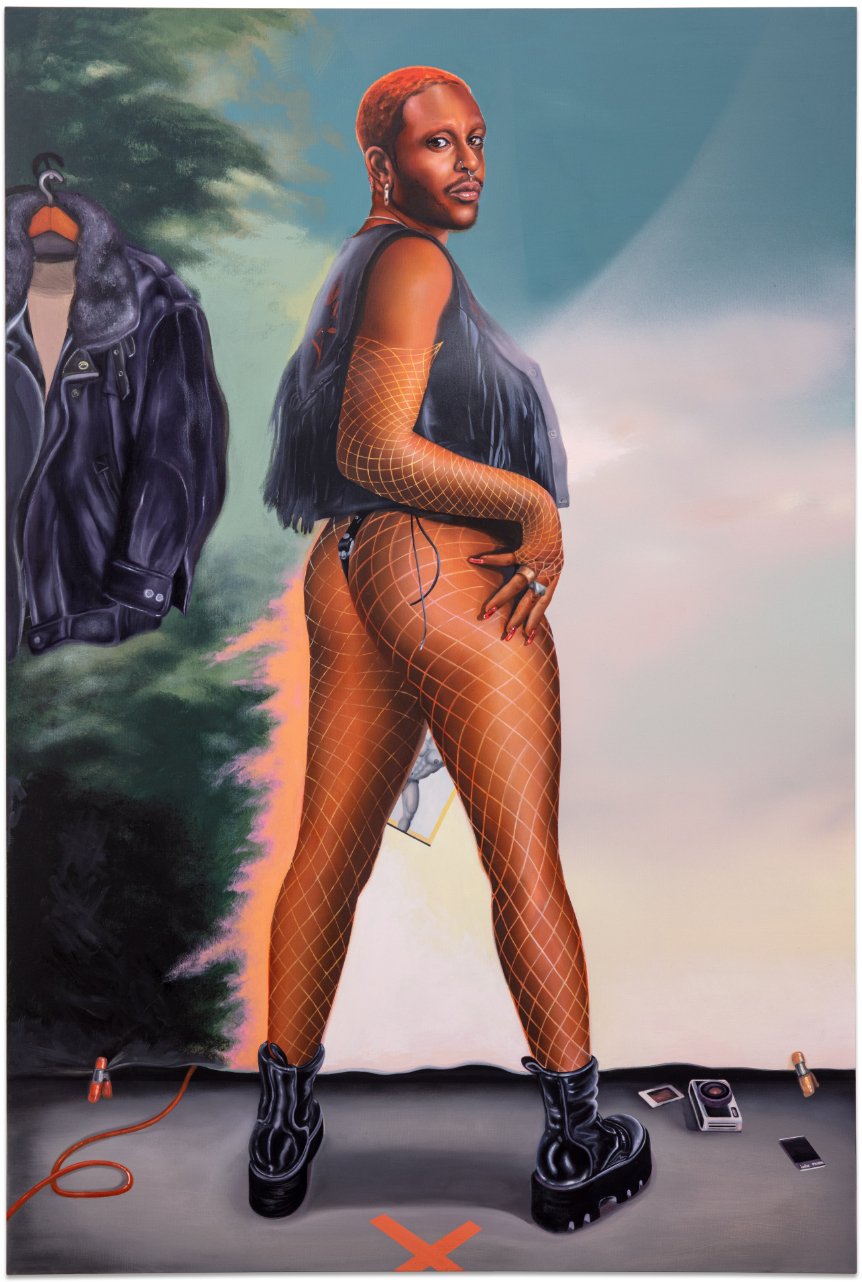

full look: Gucci

interview by Vivian Crockett

photography by Hadi Mourad

creative direction by Alec Charlip

styling by Jamie Ortega

makeup by Tayler Treadwell

hair by Rachel Polycarpe

florals by Christina Allen

production: BORN Artists

Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo, known by the pseudonym Puppies Puppies, is revolutionizing trans and Indigenous visibility through her critically-acclaimed conceptual works of sculpture and performance art. Despite a very genuine and personal embodiment within the work, an air of mystery once shrouded her identity as she initially insisted on a level of anonymity rarely exhibited by artists, particularly of her generation. In late 2017, however, this shifted with the very first reference to the artist’s gender transition taking place in her Green (Ghosts) installation at Overduin & Co. in Los Angeles. Kuriki-Olivo and her then-boyfriend lived in the gallery during the hours it was closed, leaving only traces of their existence during the hours it was open. Here, she taped two estrogen pills to the wall, pointing toward her gender-affirming course of hormone therapy—a subtle gesture that gently opened the door of visibility. Employing the mundane, everyday objects that surround her life is a hallmark of Puppies Puppies’ practice and readymades are one of her favorite ways to reference the art historical canon. An initial easter egg of visibility has since swung the door open to a state of consensual voyeurism in Nothing New, her current solo exhibition at the New Museum where the artist is occupying the Lobby Gallery with nearly constant access to her comings and goings via video surveillance, live stream access, and glass walls overlooking a recreation of her bedroom. Puppies Puppies also points to elements of her multi-ethnic indigeneity—Taíno on her father’s side and Japanese on her mother’s—with the inclusion of objects and spiritual practices that connect her disparate lineages in a form of what the exhibition’s curator, Vivian Crockett, refers to as a memoryscape. Crockett got cozy in bed for her interview of Puppies Puppies on the eve of the exhibition’s inauguration to discuss their creative collaboration.

VIVIAN CROCKETT: What were you were thinking through when you proposed this name for the show?

PUPPIES PUPPIES: There's definitely layers to it. One major aspect of the discussion around trans identity is that many people think it's something that's very new, it's something that society has to get used to, but it's not. If we look at Indigenous cultures all over the world, there are all kinds of terms for people that weren't in the binary or were considered trans. I come from an art history background, so I'm really interested in homages, but also being critical of artwork. It was a very white cis art history that I learned. So, I really also play off that, which extends to different aspects of living too. The accentuation of certain things can have a cornucopia of meaning. I'm thinking about a lot of works throughout art history. Sometimes the criticism of the work that I do is, "this has been done before," but this is the criticism of a lot of work. A discourse happens when people reference other music within their music. There's a way of thinking about these things that go beyond originality or authenticity.

CROCKETT: There's a lot about this project that feels very much in line with work you’ve done in the past, but there's elements that relate to more recent years of medically transitioning.

PUPPIES PUPPIES: With older performances, I was more concealing myself and hiding. Hiding my body, hiding any way of recognizing me. I've started to attribute more of it to body dysmorphia. It kept me from wanting to be seen. But it was also a part of my personality. Things just kind of blend together sometimes and it's hard to distinguish one from the other. As I started to transition, I was working at Trans Latin@ in Los Angeles, and spent that year really focusing on that. I felt like distancing myself from art in a way. But then, I was like, what if this is actually just an extension of my practice? And that was really exciting to me because you don't have to negotiate what you want to get out of life just because you haven't seen it in art. This exhibition really combines almost every different way that I've been working over the years, which is not easy. I often feel like painting is an observation of life, sculpture an observation of the body, or different aspects of existence. And this is very much related to observation through a performative lens.

CROCKETT: I love curating the Lobby Gallery because it's at the ground level. It's the first space that people engage with and it was originally conceived as a free space in the institution. It's a space you see from the outside and you're taking the very framework of that space as a prompt for playing with hyper visibility. Why the recreation of your bedroom? What do the various layers of that particular space mean to you in the context of your work?

PUPPIES PUPPIES: This concept has evolved over the years. The first iteration that I presented at Overduin & Co. in Los Angeles was called Green (Ghosts). Me and my partner at the time moved all of the contents of our apartment into a gallery—including our bed and everything—and we lived with our dog in the space. We slept there, but then, as soon as the gallery opened, we left. So, no one really saw the same exhibition. So, that was one iteration. And then, this iteration is actually being there, present in front of people, and there is a device to change the opacity of the glass. At any time, I can decide whether it's more of a private or public moment. The bedroom has always been something that I've focused on. Anything that I’ve lived in constant proximity to somehow becomes incorporated into the work. As a trans woman, there are certain things that make me want to not go outside. I want to stay in and dream about what could be. I think there's an aspect of that to this by putting it on display as an artwork.

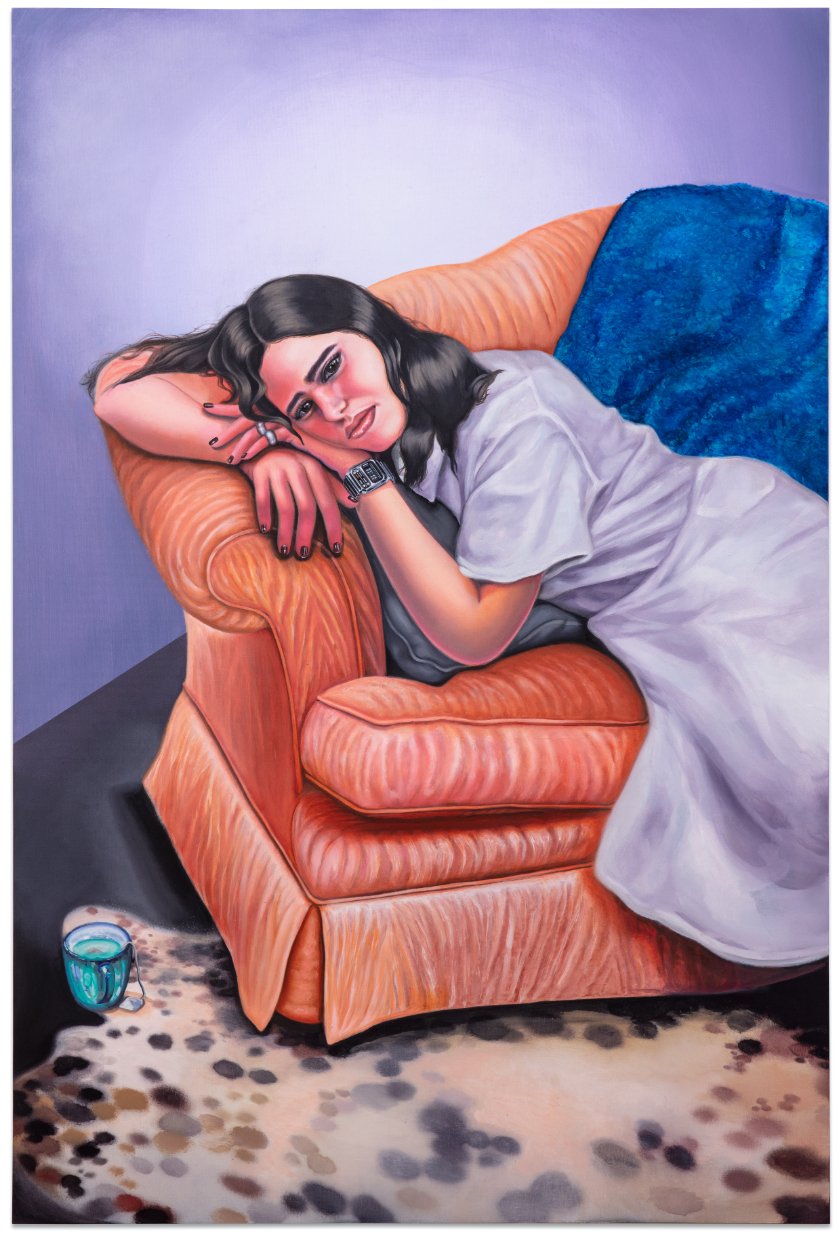

dress: Ferragamo

headpiece: Piers Atkinson

dress: Puppets and Puppets

earring: Area

shoes: stylist’s own

CROCKETT: In the bedroom part of the space, instead of emptying out the contents of your apartment, we are duplicating what's in your room. I like that it's not one-to-one. We're not trying to make it exactly the same, but we're trying to replicate the feeling of it. Earlier, we were talking about this idea of Nothing New, and how there is so much of an art historical precedent to your work, I want to emphasize that this project is very much in dialogue with different artists who have recreated their living environments, or have brought that into an institutional space. But there's also the way in which you reframe a potentially hetero-masculinist idea of a post-minimalist practice. This is a different kind of iteration of site/non-site. We've talked a lot about how Félix Gonzàlez-Torres was one of our patron saints and your work is very much in that lineage. However, there’s a new connotation to the various kinds of conceptual maneuvers that your work does. For example, the way that the physical space of your bedroom is flanked by these two other vignettes that are inside your brain, like a memoryscape, part of which reference a real place too. You are not literally trying to recreate the [Ryōan-ji] garden; it's the feeling of that garden and what it represents to you. The torii gate and the garden help delineate the threshold of the sacred space of your bedroom. And then on the other side, we are not just witnessing; we are literally looking inside your brain with reproductions of the MRI scans.

PUPPIES PUPPIES: Yeah, that was spot on. With the bedroom being sandwiched between the rock garden and the CBD garden, the torii gate is a way of signifying that you're entering a sacred space based off the Shinto religion, which is the Indigenous religion of Japan. I'm very much drawn to Shintoism because animism is a part of it. There's this praising of nature and sacred places. There are torii gates in the middle of the sea, or in the middle of the forest just to show that this is a sacred place.

CROCKETT: Green has been a central “readymade” color in your practice for many years. I love that green is simultaneously this naturally occurring thing in the world in so many different forms but then also we have green money and green screens. Can you speak a little on the significance of this color to you?

PUPPIES PUPPIES: Sometimes, when something is so ubiquitous, it can resonate with people in totally different ways, which makes it highly accessible. I went with green because it's the color of plants, of what people think of as nature. My dad grew up in the rainforest in Puerto Rico, so a lot of the pictures he has given me were pure green images from his childhood, and so it had this resonance. But I thought about it also as the mixing of blue and yellow, which have natural connotations with the sky and the sun and the sand. Later on, I got diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and so I was thinking about this kind of literalism with sadness and happiness between those colors and about these moods intersecting.

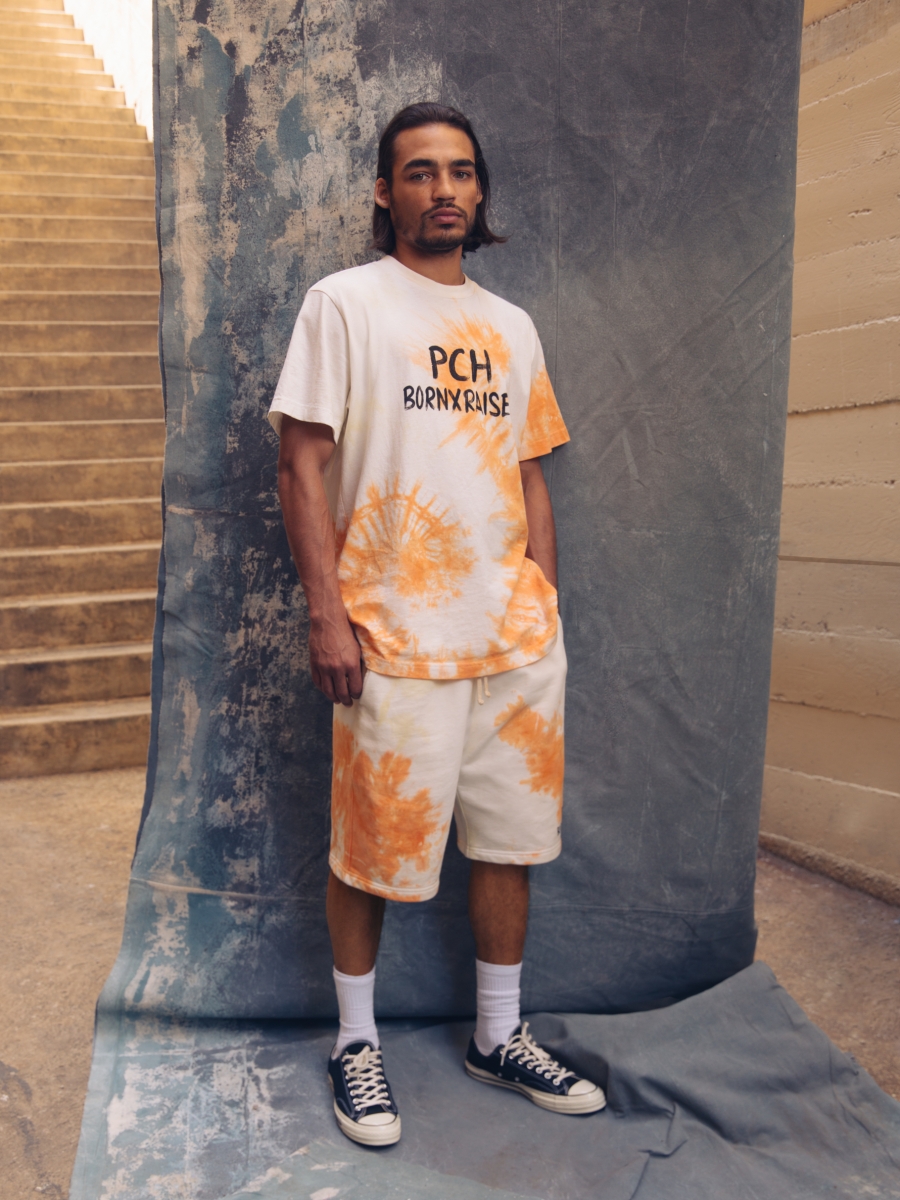

full look: Acne Studios

dress: Kritika Manchanda

CROCKETT: This other piece that the show addresses is the ways that we integrate different modes of being on display—not only the IRL display but also the ways that we exist on the internet. There's an increased pressure for us to be available to others online and through our most intimate moments. I have a private Instagram account and I'm constantly navigating who I feel like giving access to the space because it is, in many ways, a professional platform. It is part of how my identity circulates in the world. But then, there's this level of self-censorship that happens. There are different codes of respectability that we are supposed to perform. So, there’s the practice of seeing your day-to-day activities through the glass as a screen, and the fact that it'll be fogged out at times. But then, there’s the surveillance cameras filming you in the space and the fact that someone in the museum might be able to watch you in real-time, and then also be looking at you through a monitor simultaneously, and then there’s a potential third loop if you activate the live stream from your computer at home or on your cell phone. Which one is more real, or which one do they consume first, or can they do all three (or even four) simultaneously? What gets lost? What gets amplified in that mise en abyme?

PUPPIES PUPPIES: I think about that with social media because it’s mostly about trying to show your accomplishments, which I definitely participated in and was excited to participate in. You're sharing with people you love, as well as people you don't know, the things that you're doing and that you care about and what you're putting your life towards. But a part of me was like, what if I showed the boring, or the monotonous, or the in-between, or my worst? I was interested in showing all the different facets of existence, which is replicated in the show as well. There's going to be cameras within the bedroom of the museum, within my bedroom at home, and there'll be a camera recording what's going on out in the world when I go to an appointment or something that I can't miss. So, that accessibility is something that you sometimes grant to people who follow you—they know what you're doing, they can see where you're at. Nothing New is trying to get closer and closer to conveying as much as I can about daily existence, even while trying to pretend like I'm not being watched. But, you can only keep it up so long. Eventually, you're like, okay … I'm being watched, so, don't do anything embarrassing. But I think at some point, I'll have to surrender to the fact that it's constantly happening and that it'll be going on for months. It'll be harder and harder to treat it as a performance and I’ll have to lean into the idea that I'm alone as much as I can.

CROCKETT: One thing that I wanted to also mention in the context of this is that I really cherish the way that we first met. I’m on social media, but I don't follow artists just because I like their work. I don't follow celebrities. So, I often don't know what some artists look like. We met in this larger, elite space, and something drew me to you. You felt like a person I could connect with. It was like a green situation emanating from you. (laughs) But something about how we were first able to connect as people who felt an affinity that goes beyond that artist-curator dichotomy was so nice.

PUPPIES PUPPIES: Yeah, I feel the same way. It's nice when you're working on something and you also just feel a connection as two people. With something so personal, it meant so much to me to be able to collaborate with a friend that I also call a sister.

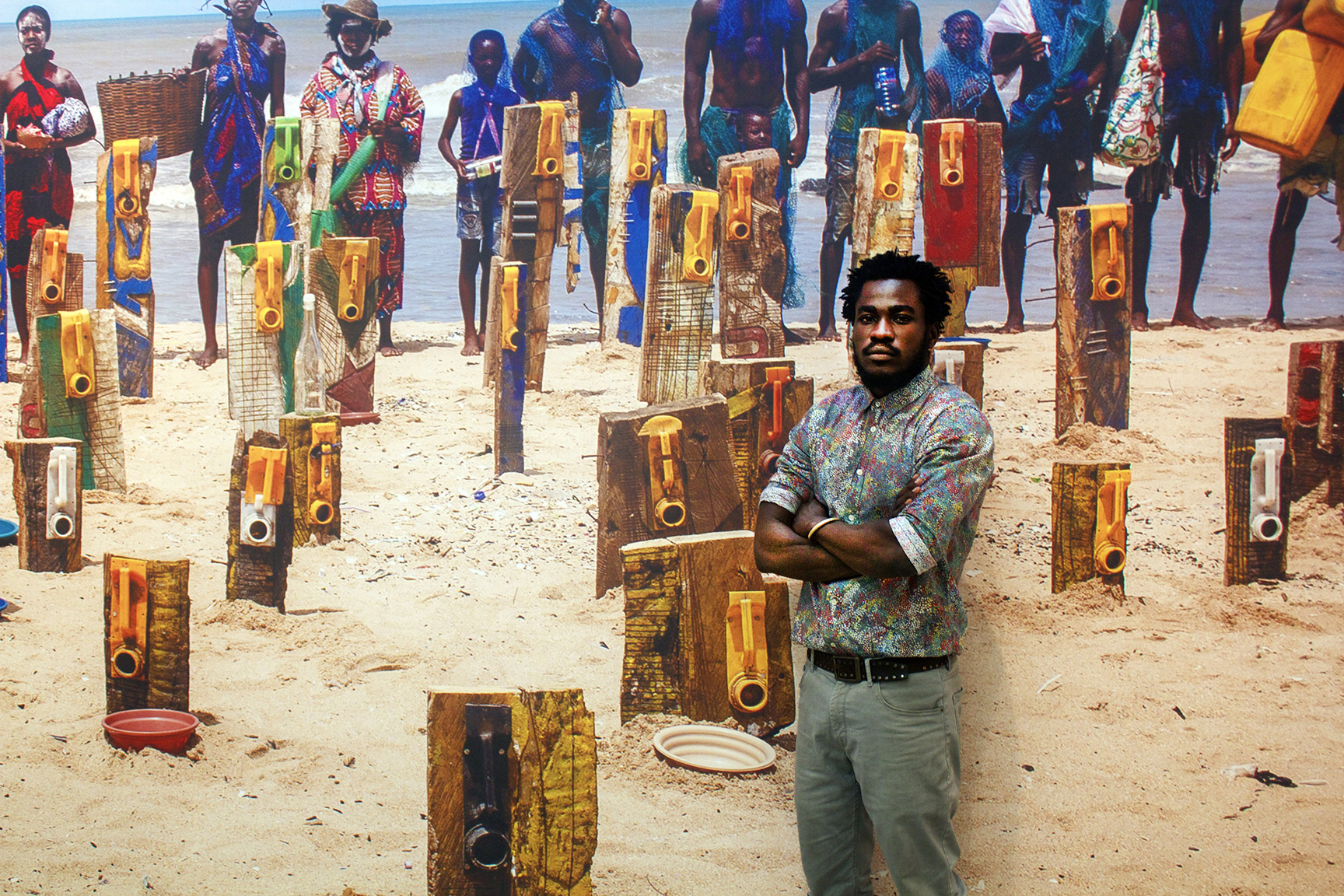

cape: Amen

![Alannah Farrell [detail of] X (Pearl Street) 2022 Oil, acrylic, and latex on canvas 78h x 50w in](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544cb720e4b0f3ba72ee8a78/1664929363203-TJY0DI2ELRJ30BSG7XWM/AFAR011+-+Alannah+Farrell+-+X+%28Pearl+Street%29+04.jpg)