interview by Summer Bowie

photos by Oliver Kupper

Defining a culture that comprises 7100 islands, centuries of colonization, and an overwhelming desire to assimilate is profound and Sisyphean. Unlike a migration that takes place over land, the ocean seems to wash away all evidence of the traveled path. The historical narrative that has framed Filipino-American immigration is fraught with this eternal question of identity and belonging. Being part Filipino myself, I learned very little about my grandmother’s life story while she was alive. It wasn’t until after she passed away and my grandfather published her memoirs that I learned just how harrowing her journey had been.

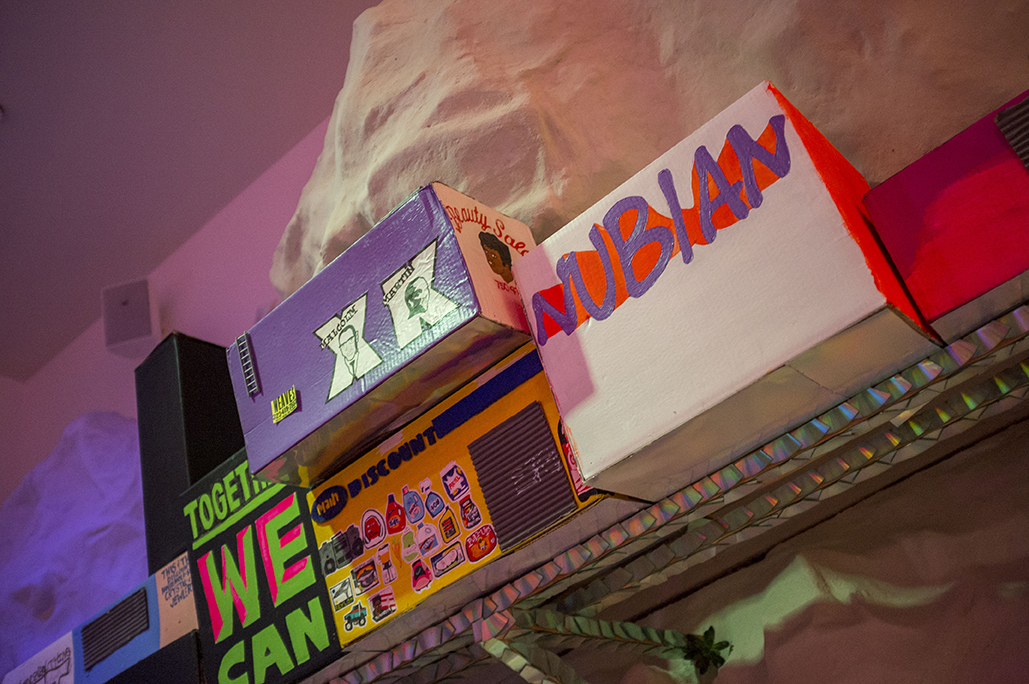

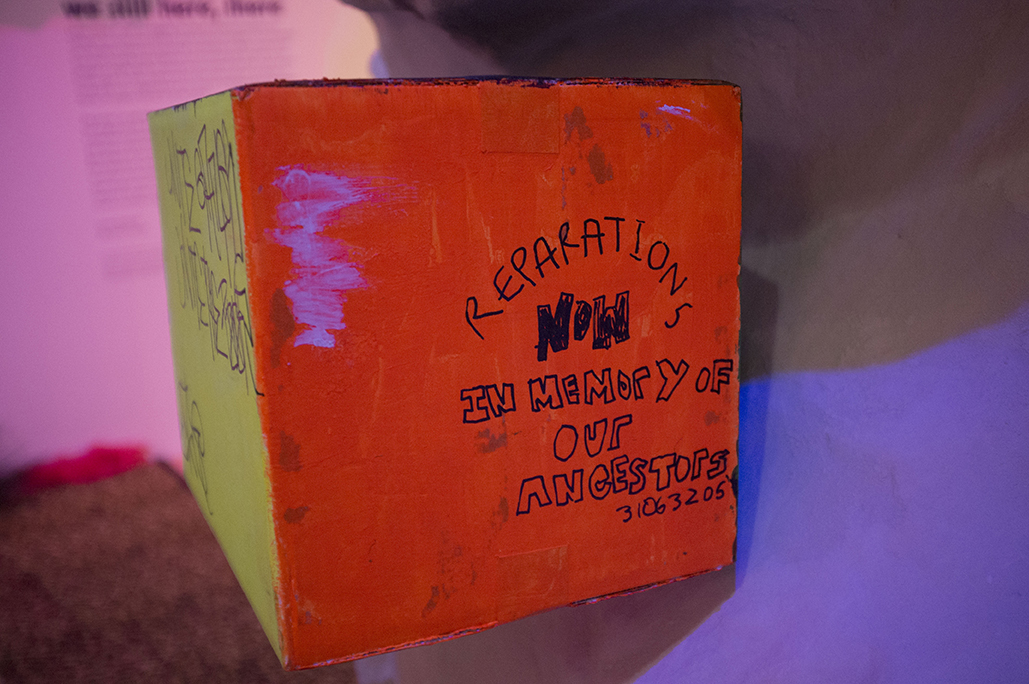

After attending the world premiere of FLEX, a dance theater piece that explores primarily the story of choreographer, Jay Carlon’s father and his immigration from the Philippines to the States, I realized that the erasure of these stories is rather commonplace. Jay’s father was not only a senior citizen by the time Jay was born, but it seems that he liked to let others tell his story for him. It wasn’t until his father passed away that Jay started to make heads and tails of the man versus the myth, and the role that he and other Filipino-Americans played in the United States throughout the 20th century, from World War II, to the Labor Rights Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and beyond. The work explores the story of Honorio Carlon and his immigration to the States, as well as that of several other Filipino-Americans and their children. This pastiche of memories serves as a paean to those whose stories have been lost in the shuffle of sublimation. In the following conversation, we discuss everything from the Filipino sartorial sensibility, to the homoerotic Renaissance paintings of “Jacob Wrestling the Angel” in the book of Genesis, to the implications that result when one must prioritize survival over preservation.

SUMMER BOWIE: First, I want to talk about your upbringing as the youngest of 12 children, and what that’s like to have such wide age gaps between both your siblings and your parents. Were you all very close?

JAY CARLON: I suppose this question is difficult to answer succinctly. My dad had 3 wives and my mom was the last. Let me provide some context: My dad, Honorio Carlon, immigrated to America in 1932 during the Great Depression, while the Philippines was under US occupation. Filipino immigrants were almost exclusively men due to gender expectations in the workplace. These immigrant men started bachelor societies for solidarity. Due to anti-miscegenation laws (anti-interracial marriage laws) these men found it difficult to start families in America. Despite this, my father married twice and had 6 children. It wasn’t until the 1970s when my dad was able to make it back to the Philippines to eventually meet my mother and bring her back to the US. Now back to the question, my siblings: 6 of them are my half siblings and the other 5 are my full siblings. Naturally, because of age and generations, I am closest to my full siblings. The strange thing is some of my half siblings are older than my mom, which is a weird dynamic having half-brothers older than your mom. My relationship with my father, however, was somewhat distant. Ever since I was born, his death was imminent. He was 74 when I was born. He kept to himself; perhaps my expectation of him as a father was to simply maintain this “Big Fish” legacy and the grandeur of his Epic, being among the first wave of Filipino immigrants in America. He lived through the Great Depression, World War II, the Labor Rights Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, etc. He never talked to me about his experiences, also I was a child, so I couldn’t really understand why any of this was important/interesting. However, doing all the research I’ve done for FLEX, I’ve been able to fill in some of these gaps in his memory, his narrative.

BOWIE: I grew up in a suburb of San Diego with a large Filipino population, and my being only a quarter Filipino meant that I had a lot of Filipino friends, but I was never Filipino enough to call the parents of my friends Auntie and Uncle the way they did with each other. Did you grow up with that idea of the extended cultural family?

CARLON: I grew up in a large Filipino community and both my parents are from the same very small island in Philippines. My dad immigrated here with a group of about 8 men, some his cousins and some his friends. Those 8 men stuck together and worked as migrant workers throughout the Southwest. Every Labor Day Weekend, they would all come together and have a fiesta. This tradition has been going on since the ‘50s and still happens today. From those 8 pioneers, there are now over 500 descendants, and we all still gather in Santa Maria, California. All those 500+ extended family members are my uncles and aunties, whether I’m related to them or not!

BOWIE: It seems like you did an extraordinary level of research into your father’s life while in the process of creating this work. Do you feel like you see your father in a different light now that the work has been fully actualized?

CARLON: Like I stated earlier, a lot of my knowledge surrounding my father’s history was from oral stories told by uncles, and aunties, and cousins. Some of these stories seemed to be conflated or exaggerated, as most memories are.

Last year, I was interviewed by an Asian periodical and was asked how my work was influenced by my identity as a Filipino American. The question really caught me off guard and I felt uneasy and confronted with this responsibility to be more or less Filipino. I am a contemporary dance choreographer. Some of my work is abstract, some of it is conceptual, and some of it is expressionistic. The general topic of my work was often surrounding migrant issues and labor rights, but as far as a direct Filipino relation to my work, I was stumped. I thought of an article that I came across by Miguel Gutierrez in BOMB Magazine called “Does Abstraction Belong to White People.” The article resonated with me and elicited introspection: as a Filipino-American abstract choreographer, what am I doing here, and why, and how did I get here? Soon after being asked the question about my identity and coming across this article, L.A. Dance Project asked me to be their first recipient of the MAKING:LA Residency, a new work by a Los Angeles-based artist. I knew I wanted to make an unapologetic work about the diverse tapestry of Southern California. My father’s, mother’s, and my story seemed to be the perfect backdrop for that opportunity to create and share a hella Filipino [untold] history.

To return to the question: the process of researching my father’s history and filling in the gaps of his narrative allowed me to create a more human understanding of who he was. My dad was this historical figure to me once I was born. I wouldn’t say we were emotionally close. I have few memories of him, some of which include dropping me off to kindergarten with whiskey on the dashboard. (Laughs), it was a different time I suppose. But I never had conversations in length with my dad. Doing all the research I’ve been doing has made him become a more human and tangible person in my life. This research has also served my relationship with my mother, who is still alive and thriving. I seem to understand her better; why she is the way she is. My mother and I never had conversations beyond the weather or my financial situation, but now we talk about memories, family back in the Philippines, and emotions (which, for a Filipino family is huge).

BOWIE: You grew up training as a competitive wrestler. How did you find dance, and how do you think your wrestling background has influenced your approach to choreography?

CARLON: My first introduction to physicality was wrestling at the Boys and Girls Club. I followed my older brothers, who joined the wrestling team to stay out of the streets. I was 5 years old when I started wrestling and competed throughout my teens. I learned partnering and momentum, strength and velocity, and nuance between force and flow. I loved these concepts, but hated competing. Wrestling is brutal. I watch videos on YouTube now and think, “Goddamn! I grew up doing that?” I found the arts in high school, first with architecture, then voice (choir), and eventually the body (dance). I knew that I could channel these learned skills into a different medium.

I am also inspired by the image of “Jacob Wrestling the Angel” (Genesis 32:22–32). The story has been depicted by many Renaissance artists in painting and sculpture form. The artworks inspired by this scripture tend to look very homoerotic. I wanted to use this image as inspiration for FLEX to represent the Filipino peoples’ resistance to colonization, and perhaps the obedience as a result of colonization. The image also reminded me of Filipino male affection, and I wanted to use this image as a way to display the way different cultures showcase affection.

BOWIE: FLEX tells the stories of several Filipino-American immigrants and their children. There’s a very militant scene, it feels like boot camp and the dancers are counting in Tagalog, I believe. Can you talk a bit about that scene and the story behind it?

CARLON: I love that scene. I wanted to integrate Filipino languages in the work. I don’t speak Visayan (my family’s dialect), but counting seemed to be a natural and relatively easy way to integrate Tagalog (the national dialect of the Philippines) into the work. We made 16 gestures/movements and gave them each a number. I noticed the sequence of movements with the counting in Tagalog sounded very militant. This section made me think of the Philippine American War (1989-1902), where the Philippines fought for their freedom and independence from America. I wanted to create a scene where the wrestling drills, something I grew up doing in America, paralleled the guerilla warfare in the Philippines.

BOWIE: The dancers you cast for this piece are all incredibly athletic, they’re poetic with their movement, and they’re multi-talented. At times they lend voice, either in narrative or song, and your choreography demands a certain versatility as well. How did you go about casting the work?

CARLON: I only cast people I trust. Trust is a very important component of my work, for the performers, the audience, all the natural and simulated elements, etc. I have worked with all my collaborators in the past on projects at REDCAT or The Annenberg Community Beach House. In my process, I like to [safely and consensually] push physical and emotional boundaries. I also like to work as a multidisciplinary director and see how I can integrate each and every individual's skill[s] into the work. The cast of FLEX is incredibly dynamic and I had a wonderful time learning about their multiple talents and how I could incorporate them into the work.

BOWIE: Your dancers seem to go through a marathon from the beginning to the end of the piece. Some of their faces were dripping within the first 3 minutes, and you see the way that the movement becomes increasingly more demanding, pushing them into a deeper synchronicity with one another. What is the warm-up and rehearsal process like for a project like this?

CARLON: I often like to focus on sensory improvisational tasks to begin a process. I like to work with eyes closed to privilege the other senses, especially touch. We start with an improvisation with eyes closed while being guided through the space. The participant with the eyes closed will recall a memory and tell that memory to the person guiding them around the room safely. This mode of embodiment and memory primes the dancers for the process of creating FLEX.

BOWIE: There are two very deep Americana references that you included in this piece, the first being the opening monologue from Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie, the second being Patti Page’s “Tennessee Waltz.” The Tennessee connection seems coincidental, but can you talk a little bit about those choices, and the Filipino rendition of the song that you included? Where did it come from?

CARLON: I wanted to create a 1950s Filipino American ballroom, a place in which my father and his comrades found solidarity--the only place they could escape and have fun without judgment. My dad loved the Cha Cha and music from the ‘50s. The Tennessee Waltz was incorporated into the work because the lyrics reminded me of the loss of their home.

We also changed “Tennessee” to “Philippine” in the live version of the song. I did this because I wanted it to be clear that these Americana attributes were coming from a sense of otherness, or perhaps reappropriation.

I was dancing with my darling to the Tennessee Waltz

When an old friend I happened to see

I introduced her to my loved one

And while they were dancing

My friend stole my sweetheart from me

I remember the night and the Tennessee Waltz

Now I know just how much I have lost

Yes, I lost my little darling the night they were playing

The beautiful Tennessee Waltz

BOWIE: The musical score was really beautiful. I think Alex Wand did a phenomenal job. How did that collaboration come about, and what was it like?

CARLON: I began working with Alex Wand on a previous project that took place in a parking lot with my car about mental health and stability. We used audio recording from the iconic moon landing as well as solar system sonifications (using the orbital speeds of the planets and creating a sound score). After that project, we became obsessed with sonifications and played with amplifying sounds of a cardboard stage, we made synth sounds activated by waves by putting Wii controllers in a buoy at the beach, and made a resonant frequency plate that used sand to predict the vibrational sound, etc. Prior to FLEX, Alex went on an epic bike tour across the Mexico-American border, biking from LA to Michoacan (the Monarch Butterfly migration path). We used field recordings from his bike ride for the ambient and environmental sounds in FLEX. I love finding parallels with Alex’s interest in ecological sustainability, like with the Monarch Butterfly migration and my interests in immigrant stories, and visible vs. invisible borders.

BOWIE: The costumes were really lovely. I understand that many pieces were from your father’s wardrobe. There’s one story you tell, called The Filipino and the Drunkard by William Saroyan. Can you talk about your father’s sartorial sense and the role that the costuming plays in this piece?

CARLON: My dad, though being a strawberry picker for over 50 years, never left the house without a suit. He never wanted people to know we were poor. He wore pressed suits and tailored clothes daily. He taught me how to shine my shoes and slick my hair back. I always felt that Filipinos had this sense of showing off, and I never understood why. When I heard The Filipino and the Drunkard, it brought to light the complexity of Filipinos not wanting to look poor, to assimilate. This is one factor why I decided to call this work FLEX--slang, to show off.

Over 70% of the costumes were sourced from my father’s wardrobe. However, the garments were quite large and boxy. Ching Ching Wong, soloist for FLEX, also served as a costume production assistant and tailored the costumes to fit the performers.

BOWIE: Throughout the show, there are times when characters can be seen in the back folding, unfolding, and refolding jackets. You also have a previous work literally called, Fold, Unfold, Refold. Can you explain this theme a bit?

CARLON: The integration of the folding in the background came out of this notion of hidden labor. I integrate labor a lot into my work. The work Fold, Unfold, Refold was a work about monotony, and repetitive gestures, and the performance of labor. I’m obsessed with the performance of labor. The folding in the background of FLEX was inspired by my mom’s immigration story. My mom lived in the shadow of my father’s epic and I wanted to pay homage to her. I thought about the invisibility of domesticity within our Western culture. I tried to incorporate as much folding in the background as possible to remind the audience of a sense of forgotten work.

BOWIE: The history of Filipino-American culture and its contribution to American development has been widely overlooked. However, Filipinos are the second-largest population of Asian-Americans, second only to Chinese-Americans. Why do you think this history is so easily overlooked?

CARLON: The Philippines is such a uniquely eclectic culture that is constantly evolving and trying to understand itself. From the 7,100 islands within the archipelago to the large amount of immigrants all over the world, Filipinos are great at adapting to cultures while still maintaining their own culture. There are so many influences, mainly because of colonization, but it’s hard to pinpoint what a Filipino is. I think assimilation, the desire to fit in, is a result of our culture being forgotten. I also think erasure is just a part of the Filipino diaspora; through centuries of resistance, the Filipino mentality is primarily survival, not preservation. That’s why I think it’s important for more Filipino stories to make their way into pop culture, and media, and academia. I think we’re getting there.

BOWIE: Where else would you like to take the work from here? It’s so emotionally compelling and educationally-rich that I could see it playing at a number of different venues.

CARLON: My dream is to share this story with other Filipino-Americans. I want to focus on touring this work throughout California, to start. From San Diego to the Bay, California is home to the highest number of Filipinos outside of the Philippines. I would also like to take the work to New York and other Filipino populated cities. It would, of course, be a dream to even take this to the Philippines.

Follow @carlondance on Instagram to learn more about FLEX.