text by Summer Bowie

When planning a pregnancy or discussing the process of birth, we often hear about the rebirth that the mother experiences—her renaissance as woman with child, giver of life, and newborn unto herself. It’s such a beautiful image when you ignore the suicide that was planned for the woman who once was. Thus is the balance of life and death, and it's one that some of us contend with more readily than others. Nothing is more apparent than this in Kim-Anh Schreiber’s Fantasy, wherein the book’s titular figure is the daughter of a mother who never stops mourning the life she should have had; her inescapable Karma.

This cross-genre novel is a disembodied lung desperately inflating and deflating itself with stale cigarette smoke and the decades-old dust of whatever room you’re sitting in. It’s a work of autofiction that is equally exposed and pregnable as it is a fictitious hallucination woven like a cosmic braid with scenes from Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1977 film, House. The intergenerational sorority of aunts, mother, and grandmother that represent the author’s Vietnamese refugee matrilineage become interchangeable with Obayashi’s highly Westernized depiction of archetypal Japanese schoolgirls and the dubious matriarchs who haunt them. The spaces within the house hold formative and traumatic memories alike. They contain cultures of sexually repressed, sisterly perversions that are devoid of sexuality, yet brimming with desire. Schreiber is wont to illustrate scenes in much the same way as Obayashi—little comedic horrors that drip with Agent Orange and irradiated uranium (respectively) over postwar rubble both seen and unseen. House makes a perfect companion for this book in the way that it depicts the domicile as a metaphor for the body. A cell that contains the bodies of all the women who have kept it.

In Fantasy, mother tongue is laced with the mysterious motherland in a braid that spans the Pacific Ocean. A language spoken between grandmother and granddaughter flourishes and fades in this boat they call home, its orbit so wide one forgets that it’s indeed moving. Only her mother’s constant motion is detected as she skirts in and out on an outlet designer dingy, leaving an inexplicably large wake each time on her way out. You can trace the roots of words that have died in the wisps that fly out of one loop or the next, having provided the foundation of their intercontinental bridge, they take an unceremonious bow and quietly escape the lexicon of their nomadic identity. “Ever since I was a little girl, I have lived in a fantastic theatron: a seeing place whose walls keep disappearing, transforming to mask, fly, tease, or torment, and beyond the walls are nothingness, and three generations of women live with me, entering through the door to rehearse their magical future, every character brought down by their character, by the desire to look good as themselves for themselves, and I alone see them, I alone beholding my house, my body, my ghosts and my gods, and my screen that is suddenly a cannibal.”

Am I really so porous that someone could just bleed into me? asks Khaos, a recurring figure whose only identifying characteristics are Daughter Flower, pregnant. Flowers constitute the form of certain characters at times, nourish them at others, and press their withering bodies into the pages of a history book from a forgotten land. Having meticulously studied a smorgasbord of allegories that portray women stuck in houses such as Mekong Hotel, Keeping Up with the Kardashians, Pretty Little Liars, The Virgin Suicides, and so on, Schreiber takes an incisive look at the corporal quality of our deepest psychic understandings and the umbilical cord that carries our identity from one body to the next. She is indefatiguably distinguishing one X from the other in her chromosomal set, knowing that there isn’t a corpus callosum dividing her dual identities, but rather an extensive sequence of yins and yangs swirling; an infinite loop of chain-smoking daisies propelling the turbine of life and death. Like the avatars of an ancient goddess, they circulate the dust that gathers in the corners of the epigenetic house, floating ubiquitously through the air, carrying traces of every dead and living thing that ever graced it with their presence.

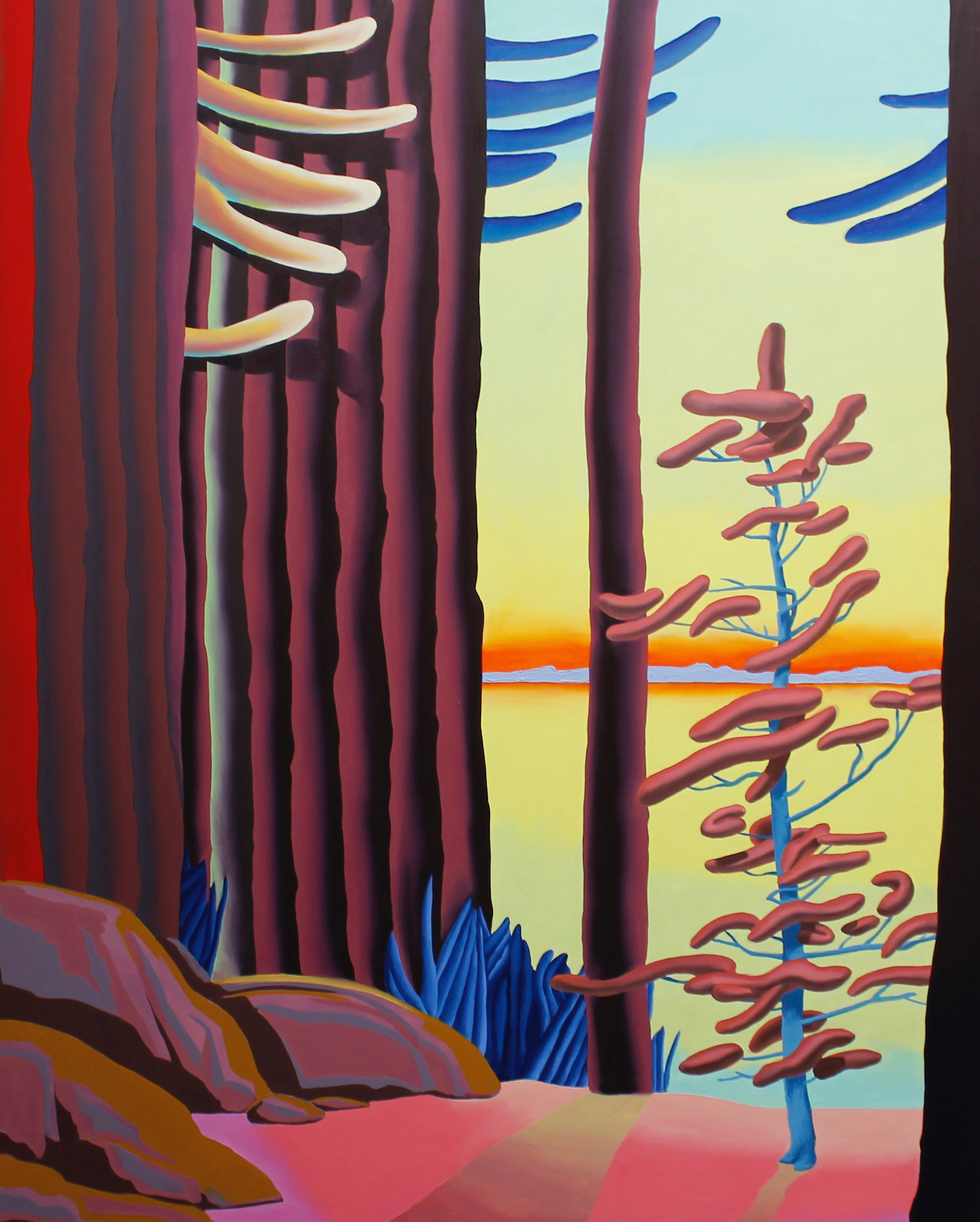

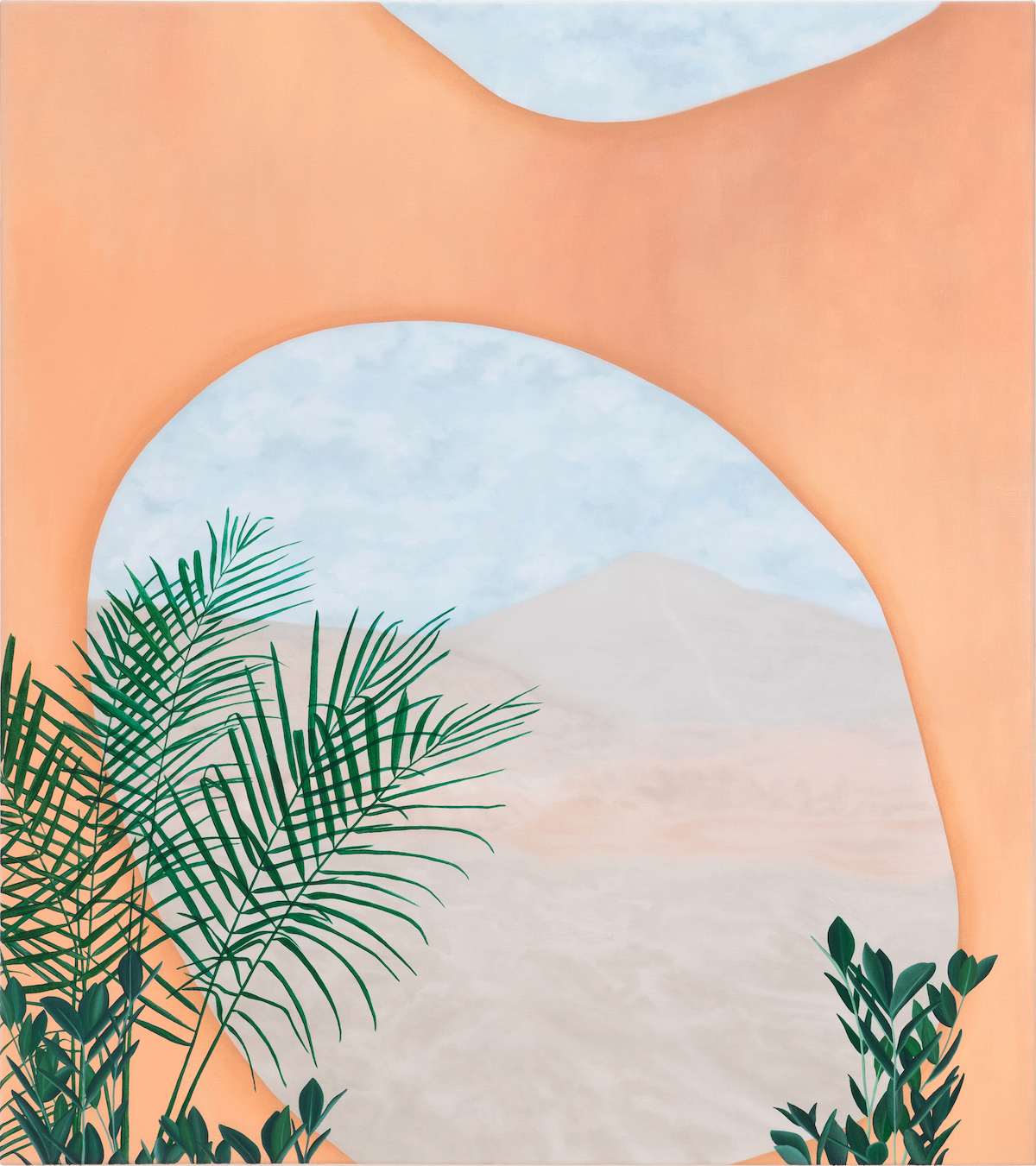

Fantasy features cover art by Sojourner Truth Parsons and is published by Sidebrow Books. Click here to preorder. Follow Kim-Anh Schreiber on Instagram.