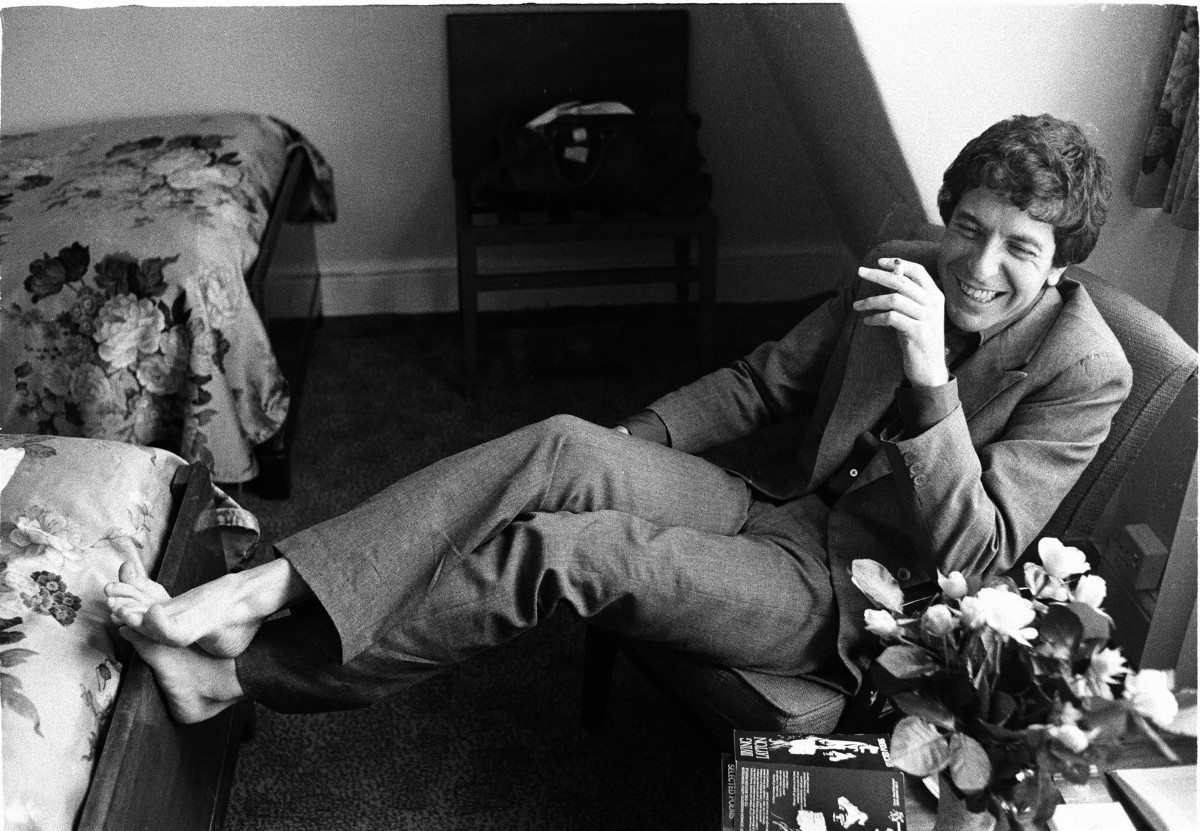

At 82-years-old and divulging his world weary outlook in an interview with the New Yorker’s Editor-in-Chief David Reminick that was published days before the release of his final album You Want it Darker and just two weeks before his death, the loss of Leonard Cohen is slightly less of a gut punch than the untimely deaths of Bowie, Prince, and Alan Vega. You Want it Darker, while lacking the conceptual heart wrench that was David Bowie’s “death as performance art” Blackstar album that came out two days before Bowie’s death, is still a lovely good bye for the multiple generations of musicians, artists and writers that were profoundly impacted by Cohen’s work. Chillingly, Leonard Cohen told Reminick, “I am ready to die,” in that premonitory profile, only to backtrack a few weeks later at a concert in Los Angeles, Cohen telling his audience, “I tend to over dramatize.” Death is ultimately a tug of war between acceptance and denial, and that conflict permeates Leonard’s later recordings. But dramatization aside, Cohen is gone after suffering heart failure brought upon by a nasty fall. My grandfather on my father’s side, my Papa, took some nasty falls as he got older. There is a visceral violence to witnessing a once strong but now frail man plummet towards the earth. When that body hits the ground, the deafening thud serves as a very metaphor for the tragedy of mortality. And yet, it’s hard to think about applying that situation to Cohen, a man who didn’t exactly exude youth but certainly projected a kind of agelessness. When news of his passing hit the Internet last Friday, Instagram memorials depicted Cohen from his ‘30s to ‘70s. He was awkwardly handsome, Remnick describing his looks as “Michael Corleone Before the Fall.”

With Leonard’s death, You Want it Darker will be obsessively editorialized by writers trying to find performance art in the act of death. That really was the case for Bowie’s Blackstar, but You Want it Darker is simply a great Leonard Cohen album full of songs about sex, love, desire, longing, loneliness, fear and, yes, mortality. That was always Leonard’s modus operandi. That is why ultimately I believe that while Bob Dylan might have had a greater overall cultural and social impact, Leonard had a far greater influence on art and music. The saying about The Velvet Underground is that while only 1000 people heard the band’s music, every one of them started bands. A similar statement could apply to Leonard. The Montreal-born poet was far more influenced by literature than he was popular music. His lyrics drew upon the symbols and semiotics of WB Yeats, the entanglements of death and sexuality of Walt Whitman, the uncanny occurrences and metaphysics of Federico Garcia Lorca, the mysticism of Henry Miller, and the puritanical skewering of Irving Layton who taught Leonard political science at McGill University and became his close friend and mentor, (Leonard once admitting, “I taught Layton how to dress. He taught me how to live forever.”). The words of these great writers built the foundation upon which Cohen would build his artistic identity. Musically, Leonard eschewed much of the music that was popular during the time he came up in the ‘60s. Though he admired Dylan, he was unmoved by The Beatles. Instead, Leonard found magic in the early blues of Robert Johnson and Bessie Smith, in the poetry heavy Country Music of George Jones, Hank Williams, and The Alamanac Singers, and the soul stylings of Ray Charles. You can also hear in his music a fascination with Phil Spector’s “Wall of Sound” production techniques (and he would of course work with Spector on Leonard’s most populist albeit still excellent Death of a Ladies Man album); Leonard’s music was often akin to a dense throb of simplistic melodies that simply served to underline his words. While he made countless beautiful songs, Leonard was true to the aesthetic and true to himself. He distanced himself from popular culture and politics and boiled down his words and music to one man and one man’s thoughts, anxieties and observations. That is fundamentally at the root of Leonard Cohen’s success and his influence on art, literature and music. Art is a selfish act: to express one’s self is to isolate one's self. Cohen was just a horny writer with a joie de vivre and a story to tell. He could only experience the world through his own eyes, and unlike Dylan didn’t aspire to do so beyond that.

There are very few musicians that have such a stylistically widespread influence on popular music. Maybe Miles Davis. Probably The Beatles. Definitely The Velvets. But it’s fascinating to examine the wildly different musicians that cite Leonard Cohen as a direct inspiration. His impact was felt immediately when he came on the scene in the ‘60s; he befriended folk singer-songwriter Judy Collins who covered his beautiful song ‘Suzanne’ and icon Richard Thompson was covering Leonard Cohen in the ‘60s with his band Fairport Convention. It was really the evocative darkness of Cohen’s work that would be emulated for decades to come, however. He set the template for troubadours singing moody and provocative poetry over dark and subdued melodies. There are the obvious avowed fans like Tori Amos and Rufus Wainwright (whose music really is a direct recreation of Leonard’s sound but sung with a more powerful voice). But Cohen’s aesthetic also proved an influence on the more experimental and willfully adventurous songwriters of our time: Bill Callahan of (smog), ANOHNI, Mark Kozelek of Red House Painters and Sun Kil Moon, and Nick Cave all owe an artistic debt to Cohen and all admit being rabid fans of the man's music. Cave has admitted that Cohen was the first artist he discovered on his own, and was already thinking of Cohen way back in the days of his maniacal goth noise blues band The Birthday Party. In fact, Cohen’s psychosexual musings can be argued as an early precursor to the whole goth movement, and his influence can be felt in goth artists ranging from Siouxsie and The Banshees to Dead Can Dance. The more literary minded alternative rock stars of the ‘80s and ‘90s worship at the alter of Leonard Cohen. Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker and R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe drew upon the symbolism and religious imagery of Cohen’s lyrics elevating their music to a more poetic reach. Cohen has even been cited in lyrics to songs by Mercury Rev and Nirvana (“Give me a Leonard Cohen afterworld. So I can sigh eternally. I'm so tired and I can't sleep. I'm anemic royalty,” sings Kurt on the band’s track ‘Pennyroyal Tea.’). There are even elements of Leonard’s craftsmanship in the most extreme arenas of rock n’ roll; his dark theatrics permeate the more recent releases of experimental doom band Earth and Swans’ most recent album, The Glowing Man, finds Michael Girl grappling with his addictions, perversions, and personal shortcomings in a most decidedly Leonard Cohen manner. As mainstream pop has grown more art friendly in the digital era, so has its embracing of the influence of Cohen. Singer/producer James Blake is a fan, as is, apparently, Lana Del Rey. Whether you think Del Rey is a product or not, there is no doubt that her music evokes a kind of sensual darkness and grapples with sexual anxiety in a way that most of her peers do not. Lana loves Leonard.

Ultimately, Leonard Cohen proved that a beat poet, a horny old man, a curmudgeon, and a morbid death obsessed narcissist could all be rock stars. He was an artist that emphasized the use of poetry and music to explore one’s inner world and exterior observations. While Dylan may have been the one who won the Nobel Prize for Literature, Cohen’s music doesn’t need awards. He created not a genre, but a mood. That mood, that AESTHETIC, has been analyzed and recreated for decades and will continue to do so. Any anxious or horny or curious guy or girl who puts some words to paper and reluctantly decides to sing them owes a debt to the life and work of the genius Leonard Cohen.

R.I.P. Leonard Cohen (1934 to 2016)