text by Luke Goebel

Let’s shake this desert rattle and see what drops out… WE are outside the Likker Barn, a little red barn with its lone-hay-bale-door open, a tapestry covering a downstairs-storefront window, & the stars are growing in number. There are Sheriffs cars and Denalis and Navigators and men smoking in the cool desert wind, and Prevost coaches—night is coming down over Joshua trees with a giant moon hovering the high desert mountains of the Mohave.

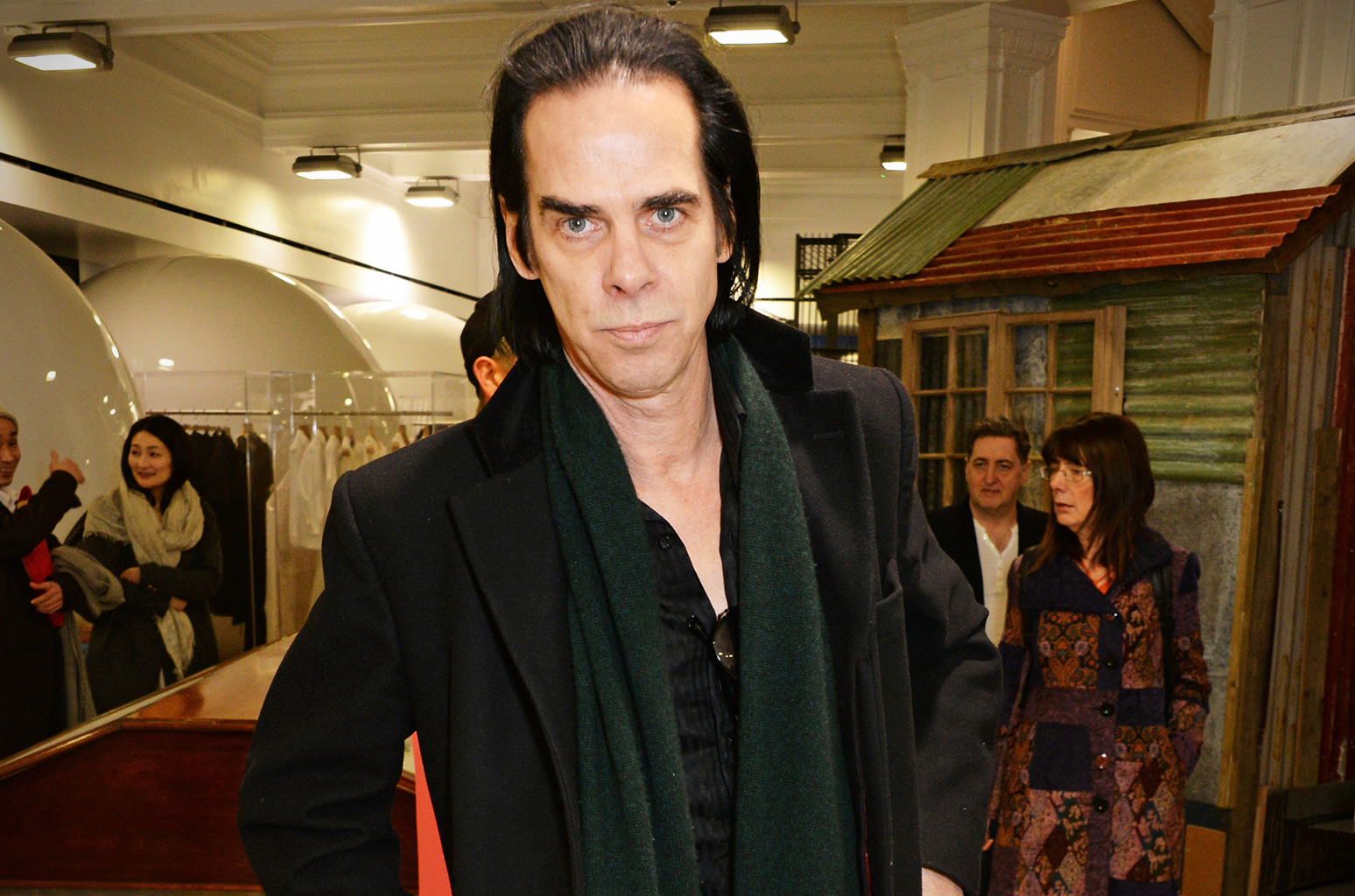

Through the bale door opening of the little barn is warm light on wood—and unseen, though heard, is Paul McCartney playing acoustic with his band, upstairs in the hay loft, singing “Love Me Do” and then three following songs (“Calling Me Back Again,” “I Saw Her Standing There,” and “FourFiveSeconds”) to ten of us sitting on hay bales and dancing in the sand in silence beneath stars—there is silence between songs and waiting, laughing and talking upstairs, indiscernible words but you can hear him when he talks and laughs—this is October 2016—with their songs is silence that can live in an acoustic hushed practice and warm-up before the show out here in Pioneertown, California at Pappy and Harriet’s. He sounds good, benevolent, what’s the way to describe the songs out here in the desert coming from this unsuspected scene? You know the Beatles?

There are clouds and Joshua trees and starry moon skies above bare, knobby rock faces of mountains, which are part of us who live here year round. A Beatle is singing.

The show tonight will be for 300 drinking lucky, nearly hip fans in the area from the Desert Trip Festival who have arrived from Canada, or Iowa, or Wichita, or wherever. People are wearing British flag fedoras and dumb things, but it’s cute, too. ISH.

What we are hearing is not the industry of the painted Prevost tour buses outside the Likker Barn, with the police cars and the Navigators and Yukon Denalis all black and chrome waiting outside the barn with those fat dressy men, smoking, in character, ready to whisk Paul and friends to the venue—it's not the lifetime of Paul hearing people screaming his name.

No, inside the little Likker Barn, in the tiny wooden barn, upstairs, with the exposed beams glowing in buttery light, the voice of Paul McCartney and his fellow band members are making music, a nostalgic love music that once changed the world. Can we even feel that anymore? It seems, in the desert, tonight, we actually can reach. It’s as if we stumbled on a manger scene of new nativity in Pioneertown.

Pioneertown is a town made as a movie-set, originally, in 1954, now inhabited by locals who stay in the old-western-ghost-town storefronts that line the one sand (pedestrians only) street through town—and we are sitting in that sand listening to church inside, something ancient to us. An old Persian American man is with us and keeps screaming Paul's name between songs, followed by Security telling us all we must leave again, to which we laugh and smile at our luck, refusing.

How many people have sat and been serenaded by Paul in a group of ten strangers? I am with a woman I don’t know and she is curious and covered in bright tattoos, we dance, I can smell her hair when it blows in the night air to my face. I’m not a Paul fan, or a Beatles nut; I’ve always liked John even with his disastrous, radical, violent flaws, and George, yes—but I bet you can’t sit outside this barn under the stars in the vast mountainous desert terrain and hear this quiet, intimate session with a Beatle, and not have some part of your inner mapping rearranged.

This Persian man’s calling of PAUL between songs is like the old man is being turned into a young teen again, plaintively calling for Paul to come down—as if Paul might appear to kiss him on the mouth. Paaaaul. The man keeps telling us to all call Paul’s name together with him. He is a drunk, lost man from a lost time when men had the plan, and it was cool to shout out the name of your idol—won’t we join him, he asks, incredulous when we won’t.

There's one last whisper of Beatlemania. And there's something else. A scale of largeness—largeness of celebrity that once unified the world’s imagination as captivated by Paul, John, George, Ringo and of course Bob Dylan, some other rock and roll stars and few cultural icons who reached that size of celebrity for the size of the gift they gave the race of human. They had everyone on their side, nearly, and created so much change—but were also men, white men, mostly—especially those to survive. There was Joni, and Janis, and Jimi Hendrix, and others, Richie Havens, but the ones who were knighted, who grabbed the entire world, who made the police and military fall for them—they were mostly white men.

I can’t help feeling that that world of unified imagination will never likely be so united again. We seem divided more and more online. There is something old, old class, old guard, the old revolutionary tides that these few living icons still hold, and the large body of women and men, and women and men of color they were part of, how can we not thank them for changing how we loved—how we imagined the world could be? How we were led to push out further from normal? To fight for love, for freedom, to take substances and to take paths of experimentation? Dylan’s lyrics, his influence on Beatle’s lyrics, and imagination.

We have different screens now, different stations tailored to our every prejudices, different axes to grind, different tastes, different self-interested dreams, angers, and triggers—we are negotiating with each other constantly in comment boxes on social media—we negotiate the way we feel, the way we express ourselves, our right to whatever we think we have right to…THINK…why others don’t have the right—and the giant world-changing idols have no place.

It’s about us, now, we think. Our opinions, our feelings, our wounds, our negotiations amidst one another—our way. I’m glad for this as I see movements like Black Lives Matter and the Dakota Pipeline Protests take root and ways in which we are taking the mantle, if not too late, as a world that is about US—our way toward change and protecting what is sacred. I am also concerned when I see how fragmented and polarized and silencing some of the online negotiations can be. The proclivity to being dour, sour, and antagonistic against anything not from the new online-erudite privileged body politic—which again I think is a good and vital thing…but we need to temper our tendency toward the sweeping rejection of all that is old, a lesson we so indubitably learned from the sins of Chancellor Mao, or ISIS even.

How do we do this in a world where the old and white and male remind us so vividly today of Donald Trump?

On the eve of the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Bob Dylan, and the subsequent outrage across the internal-webs from across the writing world, the writing industry, the writing hobbyists, the writing aspirers—I'm sitting here listening to Paul McCartney sing to so few of us and I’m being reminded of something so-far-from-now that somehow’s here living under the same sky, in the same vast desert, in our home where we live in high Mohave. I am also reminded, because of a piece I read earlier, of the song, “Idiot Wind”—It struck me in light of the idiocy of protesting Dylan as Nobel Prize recipient. I get it, that protest, but I don’t. I get it; he’s a musician, but really? Dylan isn’t a poet? Lyr|ics is a term that comes from lyre, and the ancient poets that lived in Greece long before a novel was ever written in the West were writing poetry to be performed with the lyre. With music. And the poems about politics, about the city, where did they come from, you think? Songs like “The Times They Are A-Changing” and “A Hard Rain…” what do you think they took aim to change? Where do you think they come from? The ballads are rooted in a tradition of political and humanistic and divine poetry from which sprung all literature, philosophy, and humanities, law, et al. DEAL WITH IT.

Dylan, like Paul, John, George, and Ringo, represents a small dying section of celebrity even the world of police, governments, fame, and celebrity all respected for their greatness of appeal and revolutionary participation around what was an often simply expressed love-consciousness-psychedelic-freedom revolution. And it makes sense that they are protested (online/now)—because IT was a largely white boy club that couldn’t help their gen. make the leap far enough fast enough—but the frontrunners of that artistic time tapped into and spoke for people of all demographics, genders, and spoke for the underdog, the downtrodden, and marginalized. Juan Felipe Herrera is one of that generation’s prized poets. I don't want to huff the gas of nostalgia—and I apologize that I am huffing it, down under that bale window hearing a Beatle. But there is something so pure in the voice, in the songs.

It wasn't a better time. We are where we are now still ripping down the walls of gender and race and sexuality and sexual violence, partly because of the way these unifiers spoke for many, embraced a new consciousness, and experimented against the confines of white patriarchy—less directly, perhaps in some ways, than we do today, but through play and embracing wonder, they struck. I wonder if we need a bit more of that wonder and unity to temper our passions at ripping!

It’s hard to celebrate them or us in light of all that is dire, especially planet health wise, sexism, violence, murder—the very things protest ballads take aim to eradicate. So… we often now choose to acknowledge different heroes, ones who are from the more marginalized body identity politics, because the Dylan’s, the McCartney’s, the famous white sharks of love—they failed us—but that is partly a lie.

As I said, on this eve of Dylan winning his Nobel Prize in Literature, the New Yorker published Rebecca Mead writing about the song “Idiot Wind,” paying tribute to [Dylan] she writes:

I’m glad to say that it’s been a while since I felt a personal identification with [the song]… but the furious castigation and the reeling pain conveyed by that song have spoken for me more times than I care to recall. Critics will argue about Dylan’s place in the canon, or about the rightness of bestowing a prize upon a writer whose celebration doesn’t particularly help the publishing industry. But, for my money, anyone who can summon, as a bitter valediction to a lover, the line “I can’t even touch the books you’ve read,” knows—and captures, and incarnates—the power of literature.

Idiot whining winds across the Internet against the ancient, psychedelic once-pancake-mix-face-coated radical poet singer receiving THE Nobel Prize in Literature after only having what? Changed the music world, gotten Hurricane boxer Ruben Carter out of a life sentence in prison, protesting war and nukes and corruption, racism, fueling civil rights movement, rebirthing idealism, speaking for the displaced and disenfranchised and marginalized voices around the world, freeing love consciousness away from owner mentality, collaborating with Ginsberg, subverting sexism, aiding Beats and Beatles cultural rev., feeding radicals, mystics, women musicians and poets, activists, winning Pulitzer, President’s Freedom Medal, reinventing self more times than Dow Chemical, spreading Harry Smith's anthology-driven rebirth of folk and song writing, embodying every region of USA, becoming an international figure of mystery, cowboy actor, sneering Jew-heart jaw-harp and harmonica troubadour, maintaining self as creative idol of decades, is that it! But what about winning THE prize for lit? Everyone hates it. The fuck? Dylan? Idiot wind sneering…would you give a poet a Grammy?!

I read posts about how this just legitimizes the BRO’s in literature and poetry classes who only know Dylan and fight and argue that he’s a poet while not knowing anything about the greater poetry of world. Bro: new most hated term for a cross-section of typical males—with term bro, males can be tossed into the fray of irrelevance and scorn deserving. It is a way to hate on male chromosome carrying populations and eliminate them as worthy of consideration. So, these educators who launched this attack on the notion of Dylan being valued by students, rather than seeing this as an entry into the conversation, would rather expel such students from the conversation? Rather pigeonhole students as deserving of dismissal and scorn? It seems much easier to use this as an access point, should there be students who know Dylan’s work and want to discuss it, to opening a larger conversation and including the work of great poets who are women, are diverse, etc., but I digress.

Let's admit it...It's been a bad year all around. Planet news is of bad environmental forecast. Dead seas to ride up 10 feet in decades and swallow sea cities, ocean life soon kaput, Great Barrier Reef prognosis of poor health came out today—Drumpf, Clinton, wars endless, Russia, Aleppo, terrorism, world war watch, etc. And people are outraged about Bob Dylan? Someday we may crouch before amplified speakers and listen to women and men such as Dylan sing about what no longer exists—roosters, cicadas, whales, love—objects and living things and feelings we destroyed. We need unity—and while I don’t suppose around Dylan is where we should rally—maybe we should temper the internet outcry of the week on this one?

Today, Dylan wins the Nobel Prize. Librarians, elementary and high school teachers, as well as Cynthia from The Confederate General of Big Sur are committing ritualistic suicide.

Everyone knows someone else’s more-deserving name to tweet, post, and broadcast that should have won instead (Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Marilynne Robinson, D. DeLillo)—a million times over! People can't BELIEVE THOSE SWEDISH IDIOTS PICKED DYLAN. How populist, how commercial. How gauche!!

We are trolling, Bob…

Trolls and smart folk everywhere kvetch about Dylan winning the fucking Pulitzer. Nnooooooo! Bob Dylan? What does he know about literature, poetry, and words?

He tells stories in words. He made DESIRE. Made how many thousands of timeless songs about the soul, about humans, woman, man, the oppressed, the unspeakable—that which exists in negative capability—love, moral outrage, spurn, war, criminals, Judaic crying out loneliness, wives, husbands, children, beauty, surreality, landscapes, gods, mysticism, time, space, and perhaps at best: stories that cannot be broken down to elements of story—so what? Why not Don DeLillo? This isn’t the year for Don’s. Sorry, DeLillo.

There are funny complaints. Sardonic arrows bore to the quiver in the heart of the absurdity of this year and folly of human existence. The shame. The disease of us. Throttling hate and vitriol launched at the body politic of the winners—and for good reason--MALE. And why should Dylan even be considered for a Nobel in Lit? The man the pop-fan universe first loved to hate, to boo and heckle, JUDAS—has just earned more haters—in droves. Begin Dylan's 2016 TROLLING thunder review cranking online! It's in full gripe.

How could a dirty filthy white (and in white face!) old Vincent Price-looking musician (yuck) win the glorious, erudite prize that is the pinnacle of all high literature? A music player? Goddamnit! Capital L literature. The decrepit white man (Jew), wins, in literature? He cheated! He used music! I write, ahem, cough, literature, haha, that will surely never win a Nobel, will be lucky to be novels in print in 100 years, if there is life in 100 years, maybe life on Mars???—but the reason I first wanted to write was hearing music by Bob Dylan, while being tortured by my father, while being victim to the stress, anger, hostility, violence of the male world, I first found I could live in the music (my father played) of Bob Dylan, while driving, and Dylan was there with me, somehow, actually inside of me and shepherding me in a way no other musician or writer ever has.

I first unconsciously experienced wanting to write because I was captured by his words, his stories, his objects and animals and events—his outraged yearning. I roamed insane through streets of his music and later through literal streets out of rehabs in my early twenties listening to Dylan on headphones, shivering, alone, crying, sharp-eyed. I imagined myself in his songs. I ran into words and language and writing, scrawling bad poetry, seeking what I glimpsed in his lyrics, in his stories, in the power of voice, in his magic spells. I climbed in strangers’ cars, got in dangerous situations, romanticized pain, drank, got sober, used, and dreamed of someday writing. It was male. There were women too who lived with me—Joni Mitchell and Judy Collins and Phoebe Snow. Predecessors like Nina Simone. But for a male singer, there was something Woolf-ianly hermaphroditic in the mind realms of Mr. Zimmerman’s music.

When my brother left this world I was on a street in Lisbon listening to a Dylan song I didn’t know, somehow, and had mysteriously found that day, listening to it over and over at night before a theater and crying, singing, wildly, bitterly, sobbing and singing on a street corner in another world, feeling my brother leave and not knowing yet, what was happening, why I was feeling so taken over by sorrow, by violent sorrow and madness—to sing out bitterly—having not heard the news, so that when I heard it, that moment, forever haunts me and returns to me in the middle of white nights.

I drank in a tiny apartment at 18 alone in Portland, Oregon back when a studio on NW on 21st street was 200 dollars a month and played Dylan’s music on repeat, drinking, crying, alone but with someone else’s language before I had my own.

I have lived and tripped on dreams my entire life, ones coterminous with a world I first encountered in the seat of my father’s car, a hostage to love and violence, with something outside of this world of all that I knew of what was normal and owned and patrolled—some other world Dylan offered and was a gateway into di Prima, Ginsberg, D.A. Powell, Juan Felipe Herrera, literacy.

Clearly, I am not the only author who shared an early draw to language from exposure to Dylan. Joyce Carol Oates famously dedicated her most known story: “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been” to Robert Zimmerman’s adopted stage name: Bob Dylan.

Salman Rushdie wrote, this morning, regarding the Nobel win: We live in a time of great lyricist-songwriters – Leonard Cohen, Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, Tom Waits – but Dylan towers over everyone. His words have been an inspiration to me ever since I first heard a Dylan album at school, and I am delighted by his Nobel win. The frontiers of literature keep widening, and it’s exciting that the Nobel prize recognizes that.

For me, I’m glad he beat DeLillo. Praise the lord!

The man in his liver spotted 70s. Won. The. Nobel. And. You. Can't. Complain. That. Away. This isn't democratic. What is anymore? We might think everything is. You don't get a vote for the Nobel Prize. Take to your comment boxes! Tweets! Rage. Sure…

Out here in the land of physical reality, in the Mohave high country, with the smell of suntan lotion and weed smoke, up at Pappy and Harriet's, we wait. For tickets. For Paul. For Dylan to make a rumored appearance. Having a sort of snow day.

This week is the Desert Trip Festival week-between-runs and of course Dylan, McCartney, Neil, Jagger and the gang are out here. Too many white men, true! Dicaprio, Kurt Russell and Goldie Hawn, etc. celebrities galore rented 100,000-dollar-a-night suites last weekend and others will rent them this coming weekend at the DT festival.

Early today we were in line for Paul McCartney tickets. I could care less if I got tickets. I was already scribing this story, looking for the connection between Dylan and Paul, aside from the obvious. I was in line with thousands of others hoping for tickets, waiting in the hot autumnal sun. Maybe Dylan would show. Rumors, rumors. Today, the day that Bob Dylan made the Internet furious—though, I detest when people personify the goddamn Internet. Hey, it's not real life on here. It's turning you into thinking that the world is your own giant server comment card. People are complaining bitterly on their social media complaint boxes, writing opinion pieces on why it should have been any real writer. While this is good, to have a soap box to oppose Trump's assault comments or try and raise awareness for the most recent impending doom reports on coming planet death (you'll get three likes for all posts on environment)—to stand in solidarity with and give support to the Dakota Pipeline protests—I will say griping about Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize for Literature just seems kind of pointlessly negative and perhaps in poor form.

Let's take apart the arguments against the win.

There is the formalist argument: he's music not literature. Why should lyrics count? Why should music count as literature? What's next? It's a literature prize! THE literature prize! I think we hit this one. POETRY birthed literature…it was to music.

The feminist argument (valid) that all in the camp were men this year. The race theorist argument: too white. Especially in white face.

The historicist argument: why now? He hasn't put out anything memorable in how many years?

The body-identity political complaint: why isn't it someone with less of a white penis.

Yes, he hasn’t put out anything earth shattering in years, and yes he’s a white Midwestern Jew, and yes the prizes this year were woefully all to men, and yes that’s bullshit…but should we aim our arrows at Dylan? Did he not help as an agent of cultural change in performing a miracle moving us in the directions we needed to go?

I'm so glad Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Let's remember, for a glimmer, the ancient tradition of poetry from which all literature grew. It was political, religious, and spiritual—in the religious and later humanist senses. It was how we moved from the ages of gods, to myths, to humans (Vicco). Let's remember what the purpose of poetry was back in the ancient world. Let's take a moment to remember Percy Shelley's Defense of Poetry. Let's ask the following questions:

How many protest marches were taken to Don DeLillo passages? How many men did Don D get released from prison for being framed by racist pigs and judges? How many couples have had sex to Don DeLillo? How many bad acid trips did Don DeLillo save anyone from? How many Don DeLillo books do we know by heart? Has DeLillo changed the imagination of the world through writing in the way Dylan has? Gotten anyone free from framed life prison? Dylan has inspired, has mystified, and he is a part of a world journey across the ages that has opened up the gates to wonder, to the rebirth of the ancient tradition of poetry that has always inspired and carried the human race forth in the face of tyranny, hatred, smallness, bigotry, fear, coldness, and greed.

Tonight, at the show, which I didn’t get tickets for, we stood outside having escaped the sheriff sweeps, having hung in town in friends’ homes, later coming upon that chance encounter with Paul making music in a little barn in the desert night. Then we listened in our huddled congregations outside Pappy and Harriet’s wooden honky-tonk, while Paul McCartney played a very solid rock and roll concert. They played Day Tripper, Lady Madonna, Hey Jude, I’ve Just Seen A Face, We Gonna Work It Out, I Got a Feeling, My Valentine, and five or six other numbers. Timing was immaculate in the songs. It was a strange feeling to dance under stars with Joshua Trees to Paul’s music and to close my eyes and see the stars overhead, to feel the world of my inner strangeness mixing with the outer collectivity, to be alive and in the closeness of such a major part of this world I have somehow lived in, through all the drugs and booze and sobriety and madness and loss and language…but it wasn’t a thing compared to the time we spent under the Likker Barn listening to a private practice session with Paul and thinking of Dylan and having the magic, for a moment, light up the desert and land down into us. I don’t really give a damn what the Internet thinks. The Internet doesn’t strive, and dream, or maybe it does. And maybe all of us on there should give a small whisper of thanks for what Dylan contributed, in his small way, to the continuance of wonder of the fire which is counter to the culture of violence, greed, and indifference to the marginalized. Maybe the writer from the New York Times who says Dylan doesn’t deserve the Nobel Prize in Literature is right—but he is one of a few rare human beings who have seized the world and their time on it, made writing and words and sound come alive incarnate and given rebirth to wonder, feeding the collective human soul, and carrying the torch of poetry to light the way of democracy—shared power. Dylan has carried that torch, and that time deserves recognition, as we move forward into the tough days and years ahead, with all they will entail, we need to find within us the mystery and the will to pull down from the firmament our songs, our poetry, our literature, to feed a collective world identity, and that won’t be found in the toxic comment card culture that fragments us further into our angry, over-it, fed up feeds of complaint.

The genius of the song “Idiot Wind,” is that in the end he turns the song outward and inward, singing “We are idiots, babe, it’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves.” Yep, let’s keep a bit of that, and remember, too, the magic of collectivity around something that can only be called love.

As of the time this piece was written, Dylan still hadn't responded to the Nobel panel. He apparently cares less about his winning than millions of anti-fans. Text by Luke Goebel. Follow Autre on Instagram: @AUTREMAGAZINE