Reviving the dire wolf is more than science—it is an existential meditation on theories of evolution and the meaning of life itself

text by Claire Isabel Webb

lab photos by C.K. Sample III

I

When Species Meet

It’s a burning late-August day in Los Angeles. The thicket of the city’s summer heat mixes with highway 101’s endless generation of smog. Here, at the Natural History Museum on LA’s Miracle Mile, I can smell asphalt.

Below the manicured, diligently watered grassy grounds is a massive petroleum reservoir. Oil still bubbles to the surface. For tens of thousands of years, the La Brea Tar Pits, as they’re known, have entrapped plants, prey, and predators. Sticky deaths became archaeological gold: the oil preserved a trove of Ice Age fossils of long-extinct creatures. The Tar Pits boast the highest concentration of dire wolf fossils in the world—four thousand individual animals—a species that died out at least 13,000 years ago.

Think of a Siberian husky. Now double the size, and you’ll picture a grey wolf. Imagine now a fearsome hunter larger still than a grey wolf, and stockier, with a tremendous jaw ideal for crushing bone—a dire wolf, the stuff of myth. Grey wolves, lean and loping, are built for endurance; dire wolves, scrappier, could take down powerfully muscled steppe bison and likely even young mammoths. Dr. Mairin Balisi, one of my hosts at the museum, described dire wolves as “basically a running pair of jaws.” Aenocyon dirus: terrible wolf.

Colossal Laboratory and Biosciences is a Dallas, Texas-based for-profit company that declared to have brought them back. Ben Lamm, a billionaire entrepreneur, and Dr. George Church, a Harvard geneticist, founded the company in 2021 to “de-extinct” species such as the wooly mammoth, the Tasmanian tiger, dodo, and, of course, the dire wolf, using synthetic biology. A handful of celebrity investors (Paris Hilton, Tom Brady, should we mention Peter Jackson, Chris Hemsworth?) and a few hundred million dollars later, Colossal was off to the races. The laboratory features state-of-the-art instruments and employs almost 200 people. They have framed Colossal’s experiments as conservation efforts to fill in missing niches, a curious claim because ancient ecosystems—a holistic entity from prehistoric microbes to mastadons—no longer exist and can never be brought back.

What’s more, the pups aren’t the dire wolves of old. They are not facsimiles. Colossal’s dire wolves are grey wolves with edited genomes engineered to replicate dire wolf genes—and by way of those genomics, revivify ancient traits.

Colossal’s public-facing framing of the pups as “dire wolves” signifies much more than the company’s self-aggrandizing, a marketing ploy to attract investors, or a simple catachresis. It’s a window into the fundamental destability of the concept of “species” in modern biology. It further reveals how the dogged adherence to taxonomic strictures have prevailed up to the point of synthetic biology, and are dramatically losing their utility.

To fabricate the pups, Colossal sequenced fragments of dire wolf DNA. They then used the revolutionary tool CRISPR to target fourteen genes in grey wolf embryos, making twenty changes in total, that would engender what scientists assumed are physical traits of the dire wolf—bigger, stockier, and with snow-white fur. They finally implanted the embryos into a domesticated dog. It worked. On October 1, 2024, Colossal’s team performed a Cesarean on a domestic dog, a hound mix, who was the surrogate of two purported dire wolves: Romulus and Remus. Khaleesi, a female, was born to another surrogate dog on January 30, 2025. The pups were born stark white—a ringing first indication that Colossal’s genomic edits had taken hold. The wolf pups, by Colossal’s account, are growing rapidly on a fenced-in ecological preserve at an undisclosed location in the United States, probably in the mountainous West.

*

Most media has focused on Colossal’s forgery as a mislabeling of a taxonomy and the false ontology of de-extincted animals. There are no complete genomes of dire wolves, so de-extincting a replica of a once-living individual is impossible. Moreover, there’s no such thing as an individual in a species. A dire wolf was a dynamic being who was influenced by microbes, its pack, its health, its prey—and that environment, and therefore a dire wolf’s behavior, can never be engineered in an authentic pre-historic milieu.

So what kind of a creature is Khaleesi, a grey wolf with dire wolf-adjusted DNA, born of hound surrogate? Her betweenness signifies a category of nature presently undergoing a great transformation: species.

For George Church (I talked with him over Zoom), the geneticist, Khaleesi is a dire wolf. That’s because the grey wolf genes were edited to exactly match real dire wolf DNA. The edit exactly replicated the gene from the fossil sample. Khaleesi is like Theseus’s ship: some wooden slats get replaced, but the ontology of the ship remains. The meaning of the species is afforded by genetic literalism.

For the paleobiologists at the La Brea Tar Pits, Khaleesi is a forgery. That’s because Colossal didn’t use any of the original dire wolf DNA to make her. The meaning of species here is inextricable from a long-lost time and place. From their point of view, Colossal is disingenuous. It’s like trying to pass off a new work of art as the original, and then expecting to be embraced with the same esteem and worthiness as the original that inspired the fake. Khaleesi could be likened to an artist’s reproduction of a painting, at best, that takes inspiration from a master work.

Reading Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi as biological forgeries—creatures that physically resemble the Pleistocene species but are not inherently dire wolves—nevertheless holds ontological merit. A forged painting can still be beautiful on its own terms.

For example, Dutch painter Han van Meegeren’s forgeries of Johannes Vermeer’s paintings were undoubtedly masterful. Working during the Dutch Golden Age in the 17th century, Vermeer produced relatively little during his career, making his paintings rare and therefore extremely valuable. Van Meegeren’s most famous forgery, “Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus,” is a painting that art historians thought had been lost to time (1937). Van Meegeren convinced Nazi officials, a Rotterdam museum that bought it, and a world-leading art historian that the painting was authentic. Art historian Abraham Bredius’s plaudit was that van Meegeren’s “Vermeer” was even more Vermeerish than other paintings, even while recognizing what are now considered to be glaring errors (“The masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft. . . [is] quite different from all his other paintings and yet every inch a Vermeer”).

Van Meegeren’s forgery is not important because his works convinced experts that they were “real” Vermeers. They are important because they demonstrate how van Meegeren invented techniques that redefined what could count as art. His “Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus,” like Colossal’s dire wolves, is misleading—and original. The forged Vermeers are neither facsimiles, exact copies of extant paintings, nor reproductions; they are artworks laden with authorial deceit in the style of an artist. Van Meegeren passed off his work as previously undiscovered masterpieces by Vermeer that were ontologically new but technically old. Painting almost three hundred years afterwards, van Meegeren expertly mimicked Vermeer’s style—not exact works—with such fidelity so that a non-extant “original” could look authentic.

The authorships of Colossal and van Meegeren are uncanny analogues. The artist used 17th-century canvases like Colossal used the dire wolf genome as a comparative blueprint. Van Meegeren artificially aged the oil paint by baking his works in an oven to achieve craquelure (“crackled”) effects, much like Colossal turned on and off gene expression to make the pups look like ancient wolves. And both authors took advantage of the hype, leading viewers to see what they wanted to see. In both cases, the authentic work is purported to be reality.

Yet in my estimation, the fakes are actually truly original—and worth pondering. Forgery has to do not with the aesthetic quality of the painting but with its lexical representation. Van Meegeren painted new paintings. Colossal is making new creatures. Dire wolves are biological forgeries that have much to teach us about human futures, ones that might be filled with engineered life forms we can’t yet dream up. Khaleesi, despite being passed off as something ontologically old, is truly something ontologically new—her existence heralds a new world based on that new ontology. What will that world be like with her kin in it? And how will synthetic biology continue to reshape the concept of species and being?

II

Species, Themselves

Colossal’s engineering of life illuminates just how fragile the concept of species is—and that it was never stable in the first place. What counts as a species has changed dramatically over time, from natural philosophers of ancient Greece to Charles Darwin to Colossal’s genomic scientists. Carl Linnaeus’s classification scheme in the 18th century organized creatures by physical characteristics. The textbook definition of the class Mammalia gathers together animals that are warm-blooded, have hair, and produce milk—typically.

We still use Linnaeus’s binomial nomenclature (for instance, Homo sapiens) but today, biologists generally think of a species as one that has a distinct genomic lineage that prevents it from reproducing with others. At the Natural History Museum, I hung out on a Friday afternoon with two paleobiologists, Dr. Emily Lindsey of the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum and Dr. Mairin Balisi of the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology. They look specifically at the fossil record to theorize an animal’s morphology—an organism’s form and structure—to infer its behaviors and if it was similar enough to other examples to interbreed. From the four thousand individual dire wolves that perished in the Pits, Lindsey and Balisi have learned quite a lot. The oldest dire wolf fossil at the Tar Pits is dated 55,000 years old, and the oldest recovered fossil is roughly 250,000 years old.

The wall at the entrance to the museum glows orange and displays dire wolf skulls like Nike shoes, grim trophies from the Pleistocene. The antechamber to their fossil collection is filled with shelves of skulls and weathered anatomy charts that look decades old. Though the creatures here are long dead, the lab is lively—a kind of treasure chest of bones and teeth in forms that are both strange and familiar. These forms are how paleobiologists like Balisi and Lindsey construct stories of life.

Lindsey and Balisi can’t know if two animals, perhaps with only fragments of whole skeletons that have been carbon-dated thousands upon thousands of years apart, could produce viable offspring; “We use morphology of bones to try to find consistent differences between otherwise similar organisms,” Lindsey explained. For instance, she and Balisi would recognize different species if the shapes of their molars, or if this protrusion on the humerus, was absent in that other specimen. “But it’s not because we think the morphology is the important difference in the species,” Lindsey explained. “Morphology is just a proxy for biology. It’s all we have to work with to help us figure out when we’re just looking at one bone.”

Morphology also tells the scientists a lot about behavior. Balisi confidently leads us through the labyrinthine archive. (She knows where all the bodies are buried.) She opens a drawer filled with ancient tibia, and points out where bone was broken and then regrew. From the bone’s healing, the paleobiologists can tell that dire wolves were social creatures, much like grey wolves today: if she was injured and couldn’t hunt, a wolf’s pack would continue to care for her. Balisi next guides us to a dire wolf skull, huge in comparison to the grey wolf skull beside it. The sagittal crest, where muscles connect to the skull, is marvelously massive: dire wolves crushed bones in a way that grey wolves do not. (Balisi also showed me a tray of bacula—dire wolf penis bones. Many are also broken.)

When I start talking about Colossal, Lindsey and Balisi share a look. What the company is doing, they tell me, is misconstruing the physical morphologies that define dire wolves rather than treating those morphologies as stand-ins for greater underlying principles of life and evolution. “Evolutionary relationships are really the fundamental thing that you’re looking for as a biologist,” Lindsey says.

They take turns drawing evolutionary lineages in my notebook to explain. Biologists look for the “last common ancestor” by comparing bones, teeth, and skulls, and now, partial genomes scraped from DNA samples (what’s known technically as monophyletic group: a single phylogeny, from the Greek phulē, “race, tribe.”) The last common ancestor of any species is almost always hypothetical; the Canidae branch on the tree of life that the paleobiologists sketch is messy. Twigs entwined. Branches were cut short. Canidae evolved in unpredictable ways that will always be lost to time.

For decades, paleobiologists thought, based on the strikingly similar morphologies of dire wolves from the Pits and modern grey wolves, that the two species were closely related. But in a landmark 2020 study published in Nature, and a follow-up from this past April, which is awaiting peer review, researchers were surprised to discover just how distinct they are. From sequencing genomes spanning almost 40,000 years, scientists reported that dire wolves were a “highly divergent lineage” that branched out on its own evolutionary pathway more than four million years ago, maybe six.

But this classification scheme isn’t totally clear, either. There’s linguistic confusion about the clades. It’s all a matter of how one groups a family, a genus, a species. Grey wolves and dire wolves are from different clades, a unit that organizes an evolutionary lineage by identifying a common ancestor and all of its descendants. (Biologist Julian Huxley popularized the term in the late 1950s, from the Greek klados, or branch.)

The precise evolutionary placement of dire wolves among wolf-like canids—grey wolves, coyotes, dholes, jackals, and African wild dogs—remains unsolved. Competing phylogenetic trees, all still supported by genetic evidence, suggest different possible relationships. The neat and tidy Linnean classification scheme falls apart.

One of multiple hypotheses about that clade is that grey wolves are more closely related—genetically speaking—to jackals than dire wolves. Jackals! Those crepuscular hunters who have one mate, not a pack, and that are found in Africa, Asia, and Europe—utterly different in their behavior from the rest of their clade. Grey wolves, dogs, jackals, foxes, and coyotes all share a common ancestor. And as Lindsey put it simply, “Dogs are grey wolves.” (Super cute grey wolves.)

Colossal’s own research team confirmed these results using paleogenomics. Dr. Beth Shapiro, Colossal’s Chief Scientist who specializes in Ice Age evolutionary biology, has always talked carefully about what her company is not making: Colossal is “not making clones of extinct animals but resurrecting extinct traits.”

*

Morphology is a proxy for biology. Lindsey’s phrase rings in my head all afternoon. Colossal’s forgery is getting that relationship wrong: for the company, morphology is biology.

I think of Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi as conceptual chimeras. Strictly speaking, chimeras are organisms composed of at least two distinct sets of DNA, such as twin marmosets that swap genetic material in utero, or “geeps,” the result of artificially merging goat and sheep embryos. In the pups’ case, there are at least three interacting species repping varying degrees of materiality: the dire wolf fossils that sparked them, the grey wolf that lent a legible genomic blueprint to realize the pups’ material existence, and the domestic dogs that birthed them.

The unnamed surrogate hound mutts themselves are animals that defy normative classification schemes, in this case, of “pure-bred dogs” and thus contribute to the chimeral ontology of the pups. In the womb environment, tissues mix, microbes flow, blood barriers bend; surely the what-ness of the dog surrogates further subverted the designation of “dire wolf.” And, by that measure, “dog.”

Perhaps he was the son of Poseidon, the mercurial god of the wine-dark seas. Perhaps not. In any case, Bellerophon—like all good heroes of Greek myths—exalted in his conquests and then suffered a tragic denouement. King Iobates sought to punish Bellerophon, who had been falsely accused of seducing a queen. Iobates sent the exiled prince from the city of Corinth to slay a fire-breathing monster with the body of a lion, a goat’s head on its back, and a serpent as its tail: the Chimera.

The pups are thus mish-mashes of genomic lineages old and new, extinct and extant, inspirational and material. The trio is between species. But what’s a species, anyway?

“A species is a human construct. Biology doesn’t define itself as a species, but as humans, we have a really intense proclivity to want to categorize things,” Shapiro told me at the Colossal offices in July. “There are multiple species definitions that are out there. All of them are right, and all of them are wrong.”

Shapiro’s comment highlights that the Linnean classification system was always a fiction. European explorers, when they encountered the platypus in Australia, had to bend the Linnean system to create a new category for the egg-laying mammals. Today, dire wolves are breaking, not merely bending, taxonomies of nature that have always been shoehorns to describe nature’s wondrous, multitudinous, beings. Life, too, is an unstable category.

A few years ago, I (and many others) were surprised to learn that I likely carry Neanderthal DNA, a hominid who overlapped with Homo sapiens for thousands of years. I read Clan of the Cave Bear when I was about thirteen; it’s a soapy and beloved novel in which the protagonist, Ayla, is a modern human but adopted by a Neanderthal tribe. They marvel at her ability to learn new things, to count—skills they don’t have. She is a very ugly Neanderthal and is kicked out. Later, Ayla befriends a horse and a cave lion. (It’s super 1980s.)

III

Modern Synthesis

In the 1940s, life changed.

Three scientists, Theodosius Dobzhansky, a geneticist; Ernst Mayr, a biologist; and Gaylord Simpson, a paleontologist, were architects of a new paradigm of biology called the Modern Synthesis. Their intense exchange of ideas transformed the field by braiding together principles of Darwinian evolution with an emergent, exciting science that later became known as genomics.

“Is there an explanation, to make intelligible to reason this colossal diversity of living beings? Whence came these extraordinary, seemingly whimsical and superfluous creatures, like the fungus Laboulbenia, the beetle Aphenops cronei, the flies Psilopa petrolei and Drosophila carcinophila, and many, many more apparent biologic curiosities? The only explanation that makes sense is that the organic diversity has evolved in response to the diversity of environment on the planet earth…The environment presents challenges to living species, to which the latter may respond by adaptive genetic changes.” Theodosius Dobzhansky, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” The American Biology Teacher, March 1973

Despite the title, Charles Darwin’s monumental contribution, The Origin of Species from 1859, did not explain what came to be known as “the species problem”—how, exactly, new species emerged. Of course, Darwin was not aware of genes. His theory brilliantly laid out the principle of natural selection, but lacked a mechanism for how heritable variation is created and passed on. One prevailing view was that parents “blended” together, for example, a black dog and a white dog would make a grey dog. This didn’t happen with any predictability and Darwin and his colleagues couldn’t explain why or how this occurred when it did. (Darwin theorized that “gemmules”—hypothetical minute particles that carry traits, shedding and then ending up in the parents’ reproductive system.)

Meanwhile, Gregor Mendel was working on his own theory of inheritance. Often sickly and a failure at exams, this Eastern European farm boy became a monk and later became known as the “father of genetics.” In the middle of the 19th century, Mendel cross-bred thousands of pea plants and recorded how traits like seed color (yellow or green), plant height (tall or short), and seed shape (round or wrinkled) were passed down through generations. He demonstrated that certain traits (“alleles”) can be dominant or recessive—and that those traits were predictable. (For instance, in a modern example of Mendelian inheritance, a dog with a merle coat, which is a recessive gene, should only be bred with a non-merle dog; there’s a significant chance that any offspring inheriting both recessive alleles from two merle parents can together instigate blindness and deafness.)

Though Mendel was published during Darwin’s lifetime, his work was overlooked until the beginning of the 20th century. By that point, Darwin’s paradigm of evolution was well-understood, but major holes remained. In particular, why did the fossil record show that evolution occurred over millions of years, when pea plants and Drosophila (fruit flies) could rapidly evolve in a laboratory? If “blending” was the mechanism of natural selection, why didn’t species approach one generic, one-size-fits all exemplar (how can dogs look so different)? And how did natural selection implement inherited features?

Mendel’s genomics filled in these gaps. Dobzhansky, the geneticist, showed that genetic mutations in Drosophila actually promulgated, rather than inhibited, natural selection (1937). Mayer, the biologist, developed the Biological Species Concept (1942) that defined that term by a population that can successfully interbreed (“reproductive isolation”), and that differentiation between two groups could be in large part because of dislocated environment, such as wolf packs separated by a mountain range (“geographic isolation”). And finally, Simpson, the paleologist (1944), demonstrated that the fossil record did actually accrue small changes that added up over eons, and that species, variably, could both rapidly evolve or remain static within Darwinian natural selection.

Reflecting on his life’s work two years before his death, Dobzhansky marveled at the ingenuity and dynamism of evolution. “It is wrong to believe that the world was created in six days,” he wrote in 1973. “It is more wonderful to believe that the creation is going on all the time, and that we ourselves, as parts of the created world, are privileged to witness and take part in this ever-continuing process.”

The Modern Synthesis completely reconceptualized the concept of species by cementing Darwin’s insights with Mendel’s mathematics. Species, now, were to be considered a dynamic set of beings, whose genetics and environment, over both short and long periods of time, drove natural selection (which is especially demonstrable in large populations).

The gene had been the missing mechanism. And “species” was the concept that became the coin of the realm for scientists studying the natural world—the unit of evolution. “Without speciation, there would be no diversification of the organic world, no adaptive radiation, and very little evolutionary progress,” Mayer reflected in 1963. “The species, then, is the keystone of evolution.”

*

Dobzhansky’s insight—that humans both “witness and take part” in evolution—is truer today than it was in the last century. Colossal is playing an outsized role in that.

I see three distinct threads in how humans have been and are reshaping the concept of species. First, of course, our activities have decimated many species’ environments, leading to the obliteration of whole ecosystems in which every element is woven together. We can measure the effect of our output of carbon today, correlate it to global changes such as sea level rise, and analyze how we are deeply affecting our other-than-human companions. Of course, human modifications to the environment have always spurred the evolution of other species, this has been the case since, long before agriculture. Indeed, before we called ourselves human, we participated in the ebbing and flowing of biological processes outlined by natural selection.

The second is that our co-domestication andr co-evolution with other species is necessarily bilateral. My Australian Shepherd is sprawled across my feet, twitching in her sleep, I hope dreaming of sheep she’d herd. Our co-habitation is complex; she is super sensitive to my moods. I can ask her to climb trees or leap into my arms with just slight gestures. And I marvel at her smarts. When we’re playing tag, she runs toward where I will be, calculating, in her embodied, furry way, the precise angle to run to catch me. She is not “my” dog; I like to say that I am her Human Companion Better Able to Navigate the Built Environment. We make kin.

From The Companion Species Manifesto, Donna Haraway (2003): Ms. Cayenne Pepper continues to colonize all my cells—a sure case of what the biologist Lynn Margulis calls symbiogenesis. I bet if you checked our DNA, you’d find some potent transfections between us. Her saliva must have the viral vectors. Surely, her darter-tongue kisses have been irresistible. Even though we share placement in the phylum of vertebrates, we inhabit not just different genera and divergent families, but altogether different orders.

Finally, there’s the power of precisely editing nature through artificial selection. Dolly the sheep was the first mammal to be cloned from an adult somatic cell in 1996. CRISPR, by which scientists can guide RNA to clip and replace faulty genes, led to curing sickle cell anemia in a living person.

Colossal has expressed desire to potentially evolve evolution itself on a gene-by-gene basis. They’re creating a paradigm we might call the “modern synthetics”: the redesign of living species to de-extinct ancient lineages. If the originators of artificial intelligence sought to exactly reproduce the human mind, then Colossal’s biologists are making synthetic things that have no facsimile in nature.

Colossal fantasizes about revivifying not a handful of individuals of one species like the dire wolves, but filling in what they say are ecological niches with whole populations. Mammoths could thunder across the tundras of the Arctic, hunted by saber-toothed cats and packs of dire wolves. Their work points to a new paradigm of biology that is coming into focus. How we contend with our power from the microscopic to the macroscopic will surely change how we see ourselves as humans on planet Earth, part of a rich tapestry of life that was, is, and could be.

IV

Engineering the Book of Life

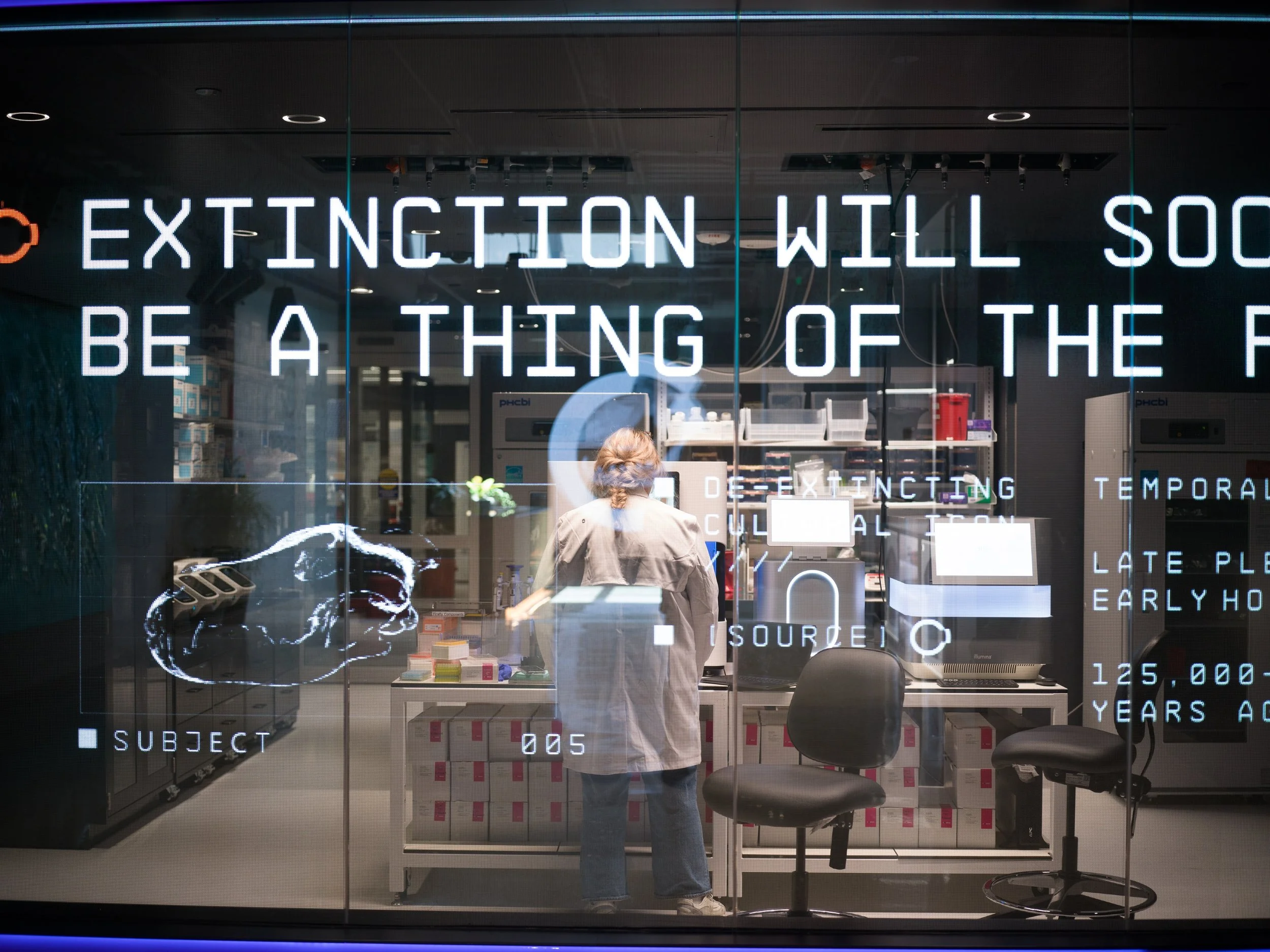

I visited Colossal Labs in July. It was Chernobyl weather—Dallas was cloaked in reddish-grey smog, emitting a nebulous sense of doom. I’m here to meet Ben Lamm, the American billionaire entrepreneur and co-founder of Colossal, and other members of the team. They’ve just moved into their permanent space, a sprawling new complex in an office park on the outskirts of Dallas. A bubbly office manager leads me through their new digs. Everyone seemed excited, but the vibe is super hush-hush. I feel like I’m in on a secret. The corridor to the lab glows with animated images of the lab’s animals-in-the-making; I’m reminded of meme coins. There’s a sculpture in the entryway: a gigantic mammoth, captured in ice that glows turquoise. Purple lighting, sleek black walls—it’s like a nightclub for scientists and their creations.

I perch on a leather bench in Lamm’s office. (He apologizes that they are still moving in.) Lamm made his fortune in tech—founding, selling, buying, and spinning off companies whose focus has, for the most part, been biological engineering and genetic technologies..

After the lab tour and three meetings, my colleague and I go searching for lunch. We decide the safest bet is a taco place, but it’s on the other side of the highway. We decide to bypass the highway by hiking through the back of the office complexes. She is in Prada flats. I admire her gumption. As we walk, scratched by reeds and sinking into the mush, I wonder aloud, “I bet a pack of dire wolves was here, like, right here.” Then my colleague points out a dead crow, mangled on the side of the highway. The tacos are terrible. We take an Uber back to the lab. We wait in what’s functionally a construction site. At 3 p.m., our meeting gets canceled.

Lamm’s self-identity as a computer programmer infuses all aspects of the company he co-founded. He and others retool and tinker with life. “I fundamentally believe that biology is just software,” he told me, invoking a well-worn trope in computer science: the cell is the hardware, the DNA the code, and evolution is the programming. According to Lamm, Colossal is reprogramming the code of life to create creatures like dire wolves. Lamm told me. “Biology is the most interesting, crazy coding language that we don’t fully yet understand.”

I like working with engineers because for them, every problem has a solution. There’s nothing that can’t be fixed, somehow. Of course, engineering the longest bridge in the world, say, is a completely different engineering than artificially evolving life. Ever the engineer, Lamm wants to find “nature-based solutions” to climate change. Lamm and his team’s tools at Colossal—DNA synthesis, genome engineering, and computational analysis—are ways to make engineering life more “efficient at evolution.” Today’s genetic engineering, as he sees it, is just in the beginning stages; soon, synthetic biology and AI will, according to Lamm, extend that engineering even beyond Earth. “We will have to become better geoengineers of this planet and then eventually off-world planets,” he said.

To make Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi, Colossal researchers first scraped DNA from two dire wolf fossils: a 13,000-year-old tooth from Sheridan Pit, Ohio, and a 72,000-year-old inner ear bone from American Falls, Idaho. They then compared those fragments with the complete DNA sequence of a grey wolf, an extant evolutionary relation. They used CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats—notice the linguistic reference here) to perform twenty base-pair edits on fourteen genes: LCORL for size; CORIN for a lighter coat; HMGA2 for skeletal morphology; and others, some of which are undisclosed to the public.

(Lindsey, the paleobiologist at the La Brea Tar Pits, is not impressed. “That they turned off their genes for color?,” she laughed. “People have made mice that glow in the dark. Making a white dog is not that impressive.”)

There are three categories of genes. First, they edited fifteen base pairs to be the exact same as those in dire wolves. Church called these the extinct traits: not just morphology, but genes unique to dire wolves. Second, the overwhelming majority of genes that remained the same (over four billion) from grey wolves. And third, the genes that Colossal chose to influence for other reasons: a white coat, a nolition for congenital pathologies.

It’s the first category that makes Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi literally dire wolves. The base pairs that make them distinct, are, through CRISPR, altered from the grey wolf genome to be chemically identical to the extinct’s.

The edits, through CRISPR, aren’t like cutting and pasting. There’s a complex relationship between the genes and how they’re expressed—including the physical traits that appear. Dr. Christopher Mason is a Professor of Physiology and Biophysics and an advisor at Colossal. He told me the scattershot nature of these edits; Colossal had to balance the fabrication of an extinct species with many possible risks. Because multiple genes can code for the same trait, the edits were deliberate choices without guaranteed results. “We could have done, in theory, many serial rounds of selection. Could we just do five edits? What’s the right number? It could take thousands and thousands of changes to really create a new species,” he told me. “After a while we realized that it’s not about the number. Sometimes you only need a handful of edits to find a new species.”

Dr. Kathleen Morrill at Colossal: “Indeed, the genome engineering team at Colossal Biosciences edited 15 regulatory regions to exactly match the extinct dire wolf genome sequences identified by paleogenomic, genotype-to-phenotype, and comparative genomic analyses. There is not a precise answer to [X changes to Y gene] due to the intergenic nature of gene-regulatory effects…This includes regulatory sequences affecting MSRB3 and HMGA2 that share a topologically associated domain, and CORIN which is part of the agouti signaling pathway.”

*

Church and I played around with the metaphor of Ship of Theseus. He smiled under his tufted salt-and-pepper beard. Here’s the paradox: As a philosophical exercise, when you replace all the wooden slats of Theseus’s ship as they wear, so that they’re eventually all new, is the ship still the original one? The answer depends on how you look at it. Is the identity of the ship predicated on its form or its matter?

Maybe dire wolves give us both answers. Swapping a piece that is chemically identical to the original rehearses its authentic materiality; swapping all the parts but keeping the same shape of the original rehearses its authentic form.

Genetics, as well as morphology, plays a role in how much one can infer behavior traces of the past. Church told me that predators hunt game as big as they can; a grey wolf wouldn’t have gone after a steppe bison because it’s simply too small. What’s unsettling is that the pups seem to be micromanaged in ways that augment their already-unnatureless. They are carefully handled and are being raised by humans (“It’s a resort,” said Lindsey.) I talked with Church about these choices. I asked why they weren’t mothered, or socialized to recreate, as much as possible, dire wolves’ early years. “My inclination would have been to have them nurse,” he said. “Also, my inclination would have been to have them trained to hunt. They are being introduced to recently killed animals as prey, but that’s very different from what you would expect.”

*

Lamm’s framing of biology as software continues a rich history of how computer programming language migrated into biology beginning the middle of the 20th century.

Richard Dawkins, the British evolutionary theorist, summed up the consummation of materiality and metaphor in this way: “The machine code of the genes is uncannily computer-like. Apart from differences in jargon, the pages of a molecular biology journal might be interchanged with those of a computer engineering journal” (1995).

But historians of science, in particular Lily Kay, see a much more complex picture. Take DNA. It’s composed of the nucleobases adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T). The human genome contains three billion base pairs. This enormous string of letters is not illuminating. The genetic alphabet all by itself means gobbledegook. To get from these bases to, say, a blue eye is very complex—less like an architectural blueprint and “more like a recipe,” according to Kay. Genes interact with each other; there are mutations; and epigenetic objects from the cell’s environment affect how the RNA codes. Multiple genes can code for the same trait, such as darker fur.

To continue the metaphor, we can try out other linguistic terms. A homophone is at least two words that sound the same when spoken but have different meanings and often different spellings. For instance, humerus/humorous, cell/sell, gene/jean. The sounding—when you speak—is the enactment of the homophone. A homonym, on the other hand, references words that sound and are spelled the same but have entirely different meanings. For instance, bare, bank, and rose are homonyms—they each have at least two meanings. Finally, homographs are words that have the same spelling but sound different, for instance, tear and beat. Sounding references the spelling, but travels on its own.

This extended metaphorical / linguistic framework maps roughly onto Colossal’s gene editing.

The spelling is the DNA: the “code” of life.

The sounding is the expression of the genes: a physical trait, or traits.

The meaning is what scientists disagree about. Colossal’s forgery is to have confused the meaning. Simultaneously, the solve to Thesus’ Paradox is that meaning is both (de-extincted) form and (replicated / re-realized) matter.

Homophones: Edited DNA that is not identical to the dire wolf’s genome but still produces the expected phenotype.

Homonyms: Edited DNA identical to the dire wolf’s genome, yielding the intended trait.

Homographs: Edited DNA that resembles the dire wolf’s sequence but fails to reproduce the intended trait.

For Church, there’s more work to do. That work will surely continue to irrupt historical notions of specieshood. “You’re not always trying to make an exact copy of something. We’re trying to introduce genes that make them resistant to pathogens. That’s neither in the ancient nor the modern genome, right? It’s something new. So, you can think of it as kind of like Dire Wolf, 1.0. It's not the final, final, final version of it, but it resembles dire wolf in significant ways.”

George Church, “Developmental biology is more than just making plants and animals. It's the whole concept of how you program linear strings to make complicated things. That is incredibly powerful. What you can do with biology is just incredible. It's atomically precise… So, if we could really get good at that programming language, developmental biology, and be able to do it in a way that doesn't involve millions of years of evolution for every step that you take, that would be amazing.”

V

De-Extinction, Baby

I’m not sure what “de-extinction” is because scientists have different meanings for it. Simply tacking on the “de” (a prefix from the Latin that often means “reverse”) to the word extinction belies a whole suite of practices that often conflict. The International Union for Conservation of Nature defines de-extinction as “the process of creating an organism that resembles an extinct species.” “Resembles” is doing a lot of work here. ICUN goes on to specify that “the legitimate objective for the creation of a proxy of an extinct species is theproduction of a functional equivalent able to restore ecological functions or processes...Proxy is used here to mean a substitute that would represent in some sense (e.g. phenotypically, behaviorally, ecologically) another entity—the extinct form.” So, according to this authoritative body, reviving an organism from extinction means it “represents” a “functional equivalent”—but how would a dire wolf plopped down in modern Montana in any way live the life its ancestors did, in the same environment, hunting the same prey, in a different climate?

For 240 millennia, dire wolves roamed from what we now call Canada to Peru. 3,000 human lifetimes ago, grim glacial planes blanketed much of North America with thick sheets of ice, but enormous animals—giant sloths the size of elephants, lions that make today’s look like docile kittens, Teratorns with wingspans of twelve feet—flourished in the forests, on the steppes, in the wetlands.

As the glaciers retreated northward, dire wolf populations dwindled. In the archives of the museum, Balisi and her colleague, Dr. Emily Lindsey, also a paleobiologist at the museum, let me hold the Pits’ dire wolf Endling—the last known individual of its species. The fossil is a deep brown, asphalt-stained lower jaw, with molars the size of one dollar coins. The label reads, “LAST KNOWN REAL DIRE WOLF IN THE ENTIRE WORLD!!” It’s carbon-dated at 13,082 years old.

Two hunting parties: padding quietly, they each surround the herd of steppe bison.

A dire wolf: a new mother, lying in wait, scenting, seeing, sensing her pack as one organism—

She is getting the measure of the herd.

A human: a lithe, fleet hunter plays the plan in their head, over and over, like rubbing a river stone.

Everyone feels it, the herd gets jumpy. Then:

They pounce!

She pounces!

Snarls and spears—the smell of bloody death like the rot of wine.

Two bison have fallen. One old, glassy-eyed, who had been awaiting death. One young, it had been its first summer.

The herd thunders away.

What’s left?

Wolf and human regard each other, these two great predators in the last great Ice Age

Our human ancestors surely encountered them.

So far, the three pups are the lab’s sole successful project that has resulted in live births. But the dire wolves are only one species in a menagerie of charismatic animals that Colossal is attempting to resurrect, such as the last thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, that died in captivity in 1936. The company is also aiming for the dodo, the quirky bird whose extinction in the late 1600s on Mauritius Island still emblemizes the folly and carelessness of humans’ disregard for nature. Colossal is using DNA that came from bone samples and then editing the genome of the Dodo’s closest living relative, the Nicobar pigeon. There are 32 million genetic differences between the two species, but they share 98% of their genomes. (Humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos also share that percentage.)

The lab’s most ambitious project is to bring back the wooly mammoth, the massive, entusked cousin of the modern elephant who stomped across the tundra for hundreds of thousands of years. Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary biologist who specializes in ancient genomics, is Colossal’s chief scientist. Her 2015 book, How to Clone a Mammoth, reads like a manual for what’s known as “de-extinction” (“Select a Species…Find a Well- Preserved Specimen…Create a Clone…Breed Them Back…Reconstruct the Genome…Now Create a Clone…Make More of Them…Set Them Free”).

“The process of generating an organism that both resembles and is genetically similar to an extinct species by resurrecting its lost lineage of core genes; engineering natural resistances; and enhancing adaptability that will allow it to thrive in today’s environment of climate change, dwindling resources, disease and human interference.” Colossal’s definition of de-extinction

Dr. Anna Keyte is the Avian Species Director at Colossal who researches artificial reproductive technologies in birds. She leads us on a tour of the laboratory. I get to wear a white coat. Gene editing birds, Keyte explains, is difficult, because one can’t make direct changes to the nucleus’s DNA, unlike with a mammal cell. “The egg is this giant yolky thing and you can't find the nucleus,” she told me. “It’s like the size of a marble in a football field.” Instead, Keyte and her colleagues inject what are called germ cells, which they design, into the embryo, which then can grow one million cells over one month to create a new, edited organism. “Bird embryos are just these amazing, gorgeous things that are coming together, self-assembling and making a living thing and that just is really cool,” Keyte said.

To make a “dodo” Keyte and her colleagues line up the genomes of the extinct bird with others. The Rodrigues Solitaire is extinct, and, morphologically, very similar: it’s also large and flightless, but is taller, more slender, and lacks the distinctive, almost whimsical beak shape of the dodo. However, the Nicobar pigeon has brilliant, iridescent green and copper plumage, a white tail, and can fly—nothing like a dodo at all. What’s curious is that the genomes don’t necessarily coordinate with birds’ physical appearances.

“I think it’s a tempest in a teapot where people are worrying about partial de-extinction versus complete de-extinction. But the fact is, once you show that you can do partial de-extinction, where we actually brought back some genes that weren't present in any modern wolf, then is it really completely out of the question that we could keep going and do the rest? It’s like when we orbited the Earth. You could complain we haven’t gotten to the Moon yet, but is it really unlikely we’re gonna get to the moon once we have orbited the Earth?” (George Church)

Colossal has set its sights to de-extinct another flightless bird, the moa, an ostrich-like animal that died off around 600 years ago. My colleague Dr. Christine Winter (Ngāti Kahungunu ki te Wairoa, Pākehā) is Māori and lectures at the University of Otago in New Zealand. “Kia ora Claire,” she writes to me in an email, a greeting that literally means “stand in good health.” Winter harbors deep concerns about Colossal’s project to de-extinct a moa that have to do with place, identity, and care—including but not merely a technical concern about any creature’s edited genetic code.

Colossal intends to remove moas’ genetic material to edit it in Dallas. For Winter, this is a violation. “Māori have long sought to resist this removal of taonga (loosely translated as treasures) from our whenua (land),” she writes to me, “Off-shoring of Māori intellectual property is not appropriate.” The Māori see themselves as caretakers, stewards of all living things—for them, everything is connected and the production of a chimera reifies, for Winter, the West’s philosophical orientation to an individual instead of a complex community, a dynamic web of life. “What sort of relationships will this de-extinct moa be able to create? It won’t be able to associate freely with its own kind, it won’t (I am assuming) be living back on whenua,” Winter writes. “It won’t be back with its traditional food sources, the bush and grasslands of Aotearoa because these are gone, sacrificed,” due to British colonialization of New Zealand beginning in 1840. “Where will it live? Will it have an existence of isolated novelty value,” she asks, “displayed like the bearded ladies of past-gone circuses, caged like zoo creatures?”

Any species only makes sense within a holistic microbial context. Dire wolves’ ecosystem doesn’t exist anymore.

Colossal’s website: “Colossal’s approach is entirely novel and not one of copying or cloning. Although relevant to many forms of scientific exploration, it is currently impossible to perform full genome synthesis of or clone extinct animals. However, our work paves the way for off-label solutions that will also benefit the at-risk species still alive today.” Liv: "I'm not sure that Shapiro and the company’s claims are necessarily contradictory but rather it’s like the fine print on a medical advertisement lol”

VI

Painting the Canvas of Life

We know from van Meegeren that art works exceed the intentions and ideas of the artist—and those who critique it. Biological forgery is art, just like an original painting. Being alive is navigating paradoxes. The neat boxes from Linnean classification were socially constructed; so too are our present definitions of specieshood.

Dire wolves were and are now part of Earth’s richness, what Darwin called “endless forms most beautiful.” Colossal, and other synthetic biology labs, hold the power to transform present forms of biology into an exquisite (undead) corpse. We get to learn about ourselves in relation to natures we can engineer and even create.

The extent to which we can now manipulate—and perhaps, soon, invent whole-cloth—forms comes with a powerful lesson. It’s the same lesson we should be learning now: humans should be stewards of Earth. That responsibility comes with a question we are all part of answering in the web of life: What will life become?

Christopher Mason is a Scientific Advisor at Colossal. “You can imagine the canvas of the future being the genome itself, and the edits you make being the paint strokes,” he told me. “People could start to create from scratch what’s in their mind, which is exhilarating and terrifying all at the same time.”