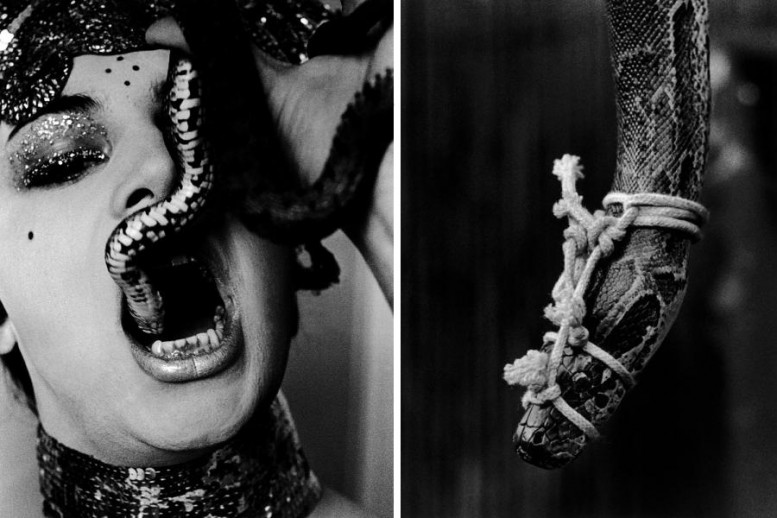

left + right: Foire de Pigalle, Paris, 1955*

Originally published in 1967, Poste Restante has become one of the most collectible photography books from the mid-twentieth century, ranking alongside the better known publications of Robert Frank and Ed van der Elsken. Strömholm’s photographic autobiography details his extensive travels across the globe in a book constructed as an Existentialist diary. Juxtaposing the urbane and the macabre, combining portraiture and street scenes with abstract photographic fragments, the book uses metaphor and visual pun in an unrelenting stream of consciousness. In its sequence and design it is a book which pre-figures much of contemporary photographic publishing and art practice.

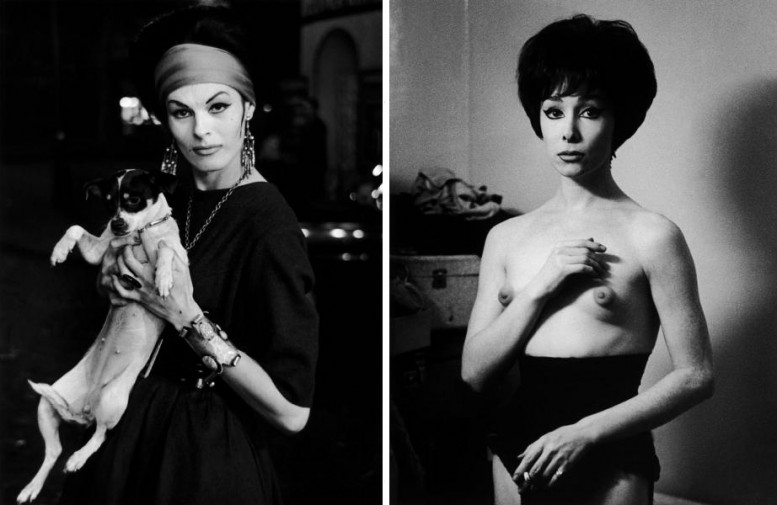

left: Jacky with dog, Paris, circa 1950 right: Cobra, Paris, circa 1960**

left: Stockholm, 1976 right: Merciful sisters, 1976***

left: Ingalill, Paris, 1979 right: The Kiss, Paris, 1962****

Poste Restante by Christer Strömholm will be available this April by Steidl books. www.steidlville.com