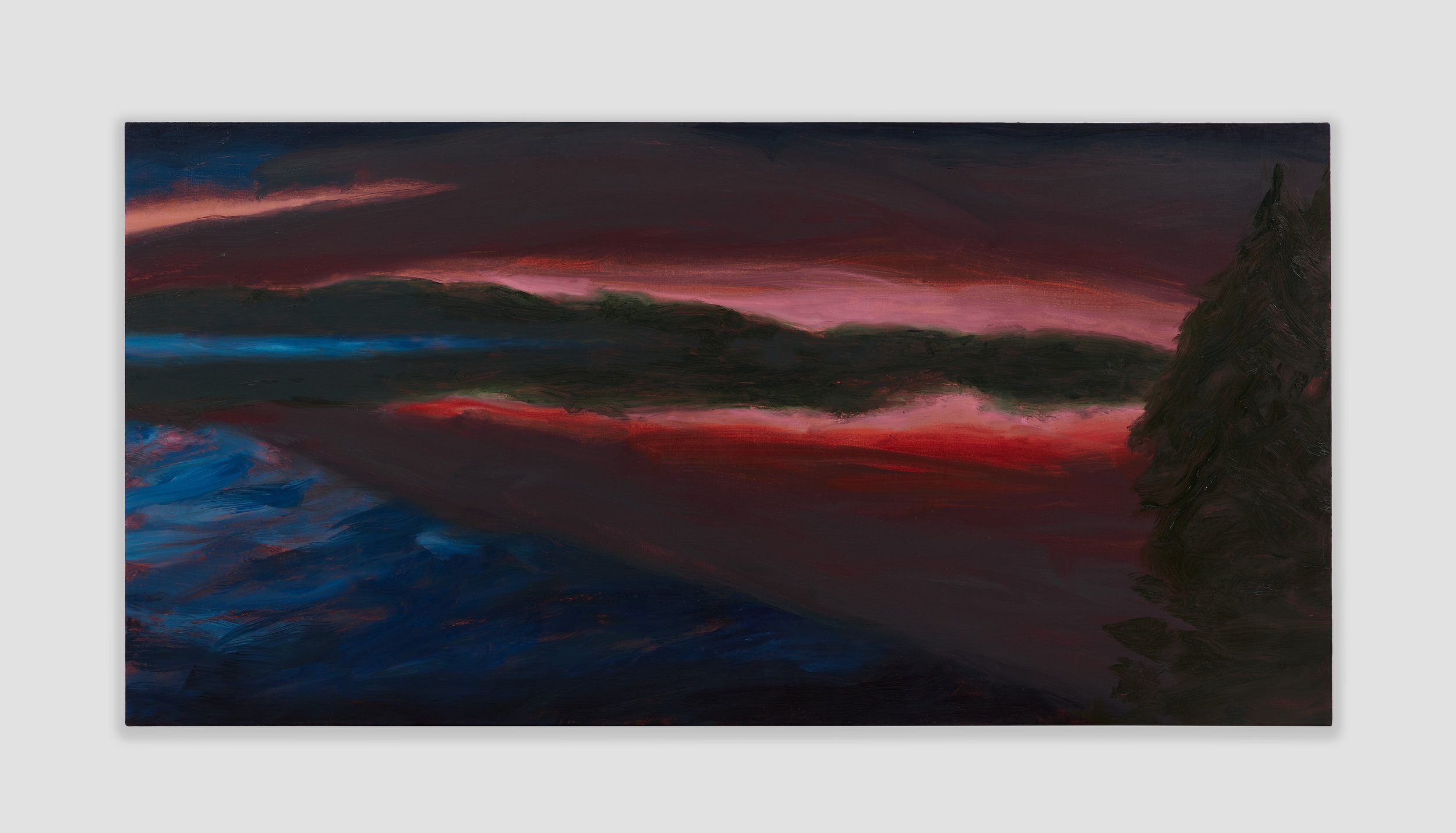

Nicole Wittenberg, Midsummer Morning 3, 2023. Image courtesy of Fernberger Gallery.

Garnering inspiration from riotous Fauvist material, Nicole Wittenberg intertwined herself with the world of art from the moment she saw Matisse’s Woman with a Hat. Rooted very confidently in her own intuition, Wittenberg has pursued interests related to her own gestural forms without much hesitation. Her artistic philosophy can be summarized by the kind of unbending compromise that turns heads and makes the world worth looking at. Imbued with synesthetic coloration, the work she portrays is embedded in its own unquantifiable emotional scale. She fearlessly plays with the kind of aggressive coloration that’s capable of conveying its own story, and her viewers get to reap the benefits. Nicole Wittenberg’s Jumpin’ at the Woodside is on view at Fernberger Gallery, a new gallery in Los Angeles. Well known for her erotica work, Wittenberg has garnered well-deserved attention for her experimentation with the body in space. After a shift in interest from figural forms to the entity that houses them, her focus turned to the landscape art we get to witness in Jumpin’ at the Woodside.

MIA MILOSEVIC: Let’s start with the opening of your debut solo exhibition in Los Angeles at Fernberger Gallery, Jumpin’ at the Woodside.

NICOLE WITTENBERG: Well…I'm really thrilled. I grew up in Northern California, I went to school at the San Francisco Art Institute, and spent a lot of time in Los Angeles in the early 2000’s. I would go down to a little apartment in West Hollywood three to four days a week and bring the artwork I did there to San Francisco. When I finished art school, I went to Italy and worked with glass sculpture in Venice for a year. I went back to California and decided to move to New York. And it wasn't for the weather! I got a job working for an artist out there. Over the course of 14 years, I started paying a lot of attention to my home state and became really interested in seeing people's attention in LA become more diverse outside of film. I would say that film has always had a huge importance for me as an artist. I spent a lot of time watching movies, writing about movies, thinking about movies, and the history of movies. I'm super excited to have my very first show in my home state in LA. It's a dream come true for me.

MM: It feels like a full circle kind of moment for you. Do you see yourself channeling your interest in cinema in this show?

NW: I have a very favorite director of photography named Michael Ballhaus, who was the DP for [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder in Germany. When Fassbinder passed away quite young, he came to LA and he shot Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), The Age of Innocence (1993) and a whole bunch of other great movies. I was interested in his work because he looked at painting for inspiration. If you go through his films, you see the way that every shot relates to a painting. I think the cinematic space is one where you have an immediate impact, and it deals with the constraints and scale in a way where it presents itself all at once. That’s the way I seek to construct a painting. Even if you just see a painting for 10 seconds, my goal is for the viewer to receive a whole and complete experience. Because film is about moving images, the image for me is much more important than the narrative. The image defines the narrative and not the other way around. The narrative is oftentimes personal in film, like we could all go to see the same movie and leave with different ideas about what that narrative means. That's because we all have a different kind of experience with images.

MM: Tell me more about the title of the show, Jumpin’ at the Woodside. Did you choose the name?

NW: I did. It's a Count Basie song. I really love jazz. I love the way it moves us through things, and it doesn't sit still. I think that's a really nice way to think about images because, even though paintings are static and films are in motion, paintings can have just as much motion as cinema. Jazz also positions itself towards motion, momentum, and a clear feeling. I felt like all these things are in conversation with one another in this show.

MM: The press release for the show quotes Pierre Bernard in its description of your work, stating that “Color has just as strong a logic as form. It's a matter of never giving up before one has managed to recreate the first impression.” What do you think of color having as much logic as form?

NW: I would say color creates an overall tone, which conveys a sensation, and the feeling is the thing that the image carries. Depending on what kind of painter you are and how you want to use color, it tells you a lot. In abstract painting, color conveys an image and a form even when it has been separated out from its descriptive form.

MM: The idea of color is very relevant to your upcoming show. How did you think about color in this selection of work?

NW: For the show I was really thinking about the vibrancy and chroma as the colors being distinctly of themselves, and how you could get high chroma, high velocity color to push against its neighboring colors to create a more aggressive and fast-coming image.

Installation view courtesy of Fernberger Gallery.

MM: What were some of your earlier interests? What brought you to painting?

NW: I would say as a youngster, I was really attracted to painting. The paintings that have my first memories of them are at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. We have early Matisse paintings that are my first memories of seeing paintings in real life. They're the early Fauvist paintings, and they were the birth of the Fauvist movement. San Francisco holds the Woman with a Hat (1905), which I think may have been the first really definitive Fauvist picture. Matisse created a painting where the content of the painting really was color. It's not really a portrait, it's more of a conveyance of riotous color. I was able to see that painting at a young age and it was the thing that I was most attracted to at that age. It was the most interesting thing I'd ever seen. It never really left my memory. I was younger than 10 when I first saw that picture and I just wanted to go back and see it again and again. It never got boring.

MM: And there was a progression from then, to painting, to art school, to your career now.

NW: When I was 16, I had back surgery and I had to spend a year in bed. I spent a lot of time in bed copying classical drawings because I didn’t have much mobility and that was something I could do. I spent a long time drawing, and drawing is a really important activity for me. I spent a long time copying old masters. I had a couple of books of etchings, Rembrandt's and Goya's. I spent a long time copying those etchings and making drawings of them. When I was in art school, I needed another back surgery. It was another year in bed and lots of looking at images, lots of looking at drawings, and the copying of classical drawings continued. When I was living in Venice after art school, I had a really great opportunity to spend a lot of time with my three favorite painters, which I would say are Venetian painters: Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese. I had a lot of off time and I didn't really know anyone in that city, so I would go and make copies of those works and spend time with works that really dealt with color, scale, and motion.

MM: It seems like you're known for reinventing realism, your name is often in the same sentence as the reinvention of something new or original. It's interesting for me to hear you say that a lot of your process started with copying.

NW: I would say it's more like stepping into a feeling rather than copying an image. When I'm looking at something, I get a feeling for it. That feeling dictates what the image becomes, and it's not really a depiction of exactly what I'm looking at. If you were to see a photograph of the image, like the places where I was when I was working on the studies, I don't know if you would see anything close to what the paintings look like. There's big jumps between what I see and what I feel when I'm looking at it. I want the paintings to be a depiction of the feeling, not of nature necessarily. I'd say a big part of that has to do with what you put in and what you leave out. I'm always trying to convey a feeling of being in that moment, and that feeling of being in that moment is something that's fleeting. The image coming forth all at once has to do with the fact that the feeling disappears as quickly as it arrived. It's a flash.

Nicole Wittenberg, Strawberry Moon, 2023. Image courtesy of Fernberger Gallery.

MM: The Elle Magazine article by John H. Richardson which reviews you and your work cites Judith Bernstein, who said that “women who work with sexual imagery are often lumped together when in essence their aesthetic and message are very different.” What are your thoughts on that?

NW: I would say that it may be a cultural fascination to see women, who have oftentimes been the subject matter, to be able to pick up that same subject matter as the historical subject. Judith Bernstein is a fabulous artist, but she's a very political artist. She uses sexualized imagery as a way of talking about power structures in the world and pushing back on those power structures. I'm not really interested in politics at all. Erotica paintings for me started in a really funny way where I was watching a lot of movies, and I was talking to my friend in LA, and I was saying that I felt like I'd run out of movies to watch. Like, I don't know what's going on. I'm just bored with everything. And he was laughing. He was like, “you know, porn is like 80% of the internet.” And I was like, “what?” And he's like, “yeah, it's like 80% of the internet.” And I was like, “stop.” He's like, “yeah, go to Pornhub.” And I was like, “okay.” I go into the internet and I look up Pornhub and I get all this really boring porn and I'm just like, this is really boring. I end up discovering amateur porn, which turns out to be a very interesting part of porn for me. I was like, wow, this is kind of fantastic, because I couldn't really figure out why it existed. The people who made it weren't getting paid for it. What are they doing? What is the draw here to this? I couldn't really figure it out. And then I started putting in really weird search terms like “sunsets” or “back to nature”, or for the piece that John [H. Richardson] wrote about, I had put in the words “Laura Ashley”, and came up with images of teenage boys jerking off in their mother's bedrooms. I was like, wow, this is totally insane.

MM: It sounds insane.

NW: I ended up taking a bunch of screenshots and then just watching them and drawing, because I can draw pretty quickly. I was just watching things and pulling pieces of stuff together and collaging it and creating imagery based on queries in amateur porn. That's how the erotica really came about. A lot of it is set in nature, which is what pushed me towards landscape painting.

MM: It’s interesting how porn is usually represented indoors, or it would be weird for it to be outside, but then you make this transition to outside…

NW: I was totally interested in the outside part. I was looking mostly at international porn, so I was looking at a lot of German porn shot in forests, some beaches, some hiking trails, some old porn from the 70’s shot on mountaintops. It became interesting, and then suddenly the figuration fell out and I just started looking at the stuff around which became just as interesting to me as the people.

MM: Some descriptions of your work note the “awkwardness of bodies”. This is an interesting contrast to nature which doesn’t seem to be capable of awkwardness?

NW: Nature has a lot of awkwardness, too. There is an awkwardness to porn, but it's more about the awkwardness of the camera than the awkwardness of the body. I tried doing the erotica images with models and it became a little too weird. The landscape work came out of having more autonomy with putting together firsthand experiences.

MM: A lot of the erotica work that you do is cited as something controversial or innovative because you’re a woman representing sexualized male bodies. There seems to be a recurring narrative about it being controversial. What do you think?

NW: I was using men and women, but there was a lot of male imagery because there's so much of it in porn. It was also really fun to turn the tables. If the male gaze is such a dominant viewer of the female form, why can't the female gaze be a dominant viewer of the male? Now we've entered an era where male and female can be self-declarative. Where there is no longer this border, this edging out of what is male and what is female. What we get to decide in 2024 is what pronoun we'd like to associate with ourselves. I could be a man because I say I'm a man, not because of how I was genetically assigned at birth. We've moved into an era of fluidity, of gender that didn't exist 20 years ago. If it did exist, it was as fringe culture. It's the pushing of boundaries that allowed for that fringe culture to be part of the language of our dominant culture.

MM: Now there are more than two gazes.

NW: Yeah, and now we can decide which gaze we would like to have. The one most natural to us.

MM: That touches on your rejection of identity art.

NW: It does because we have more voice in being able to describe and portray our own identity. It expands the notion that we must stick to a singular identity, the identity that we must portray in our everyday lives–in our art, writing, voice and participation. There’s more gray area.

MM: And more room for creativity in art.

NW: More room. I think art has always asked culture to give it more room. And how much room are we allowed to have? It allows us to push back on the constraints of identity.

MM: How much room can be assigned to one person?

NW: How much room? How many little boxes can we check? We're all presented with these little boxes, and we’re meant to occupy these boxes fully, but we're not meant to expand to the adjacent boxes.

MM: On the topic of gendering things, you've talked about some of your techniques being dominated by a “big muscular brush stroke.” I love this in the context of what you have painted, like sexualized males and whatnot. But then it's also interesting to think about how it relates to your landscapes.

NW: I think that just comes down to who we are as people and how we like to communicate, because we all have such different styles of communicating and the way we paint, or the way we write, or the way we talk. It’s all so specific to who we are. I'm a direct, all at once, big gesture kind of person. The interesting thing about painting is how much we reveal about who we are when we're doing what we're doing. We can't really hide in that.

MM: The choice is inevitable. Do you see a similarity between your erotica art and these current landscape paintings? Do you feel they fuse together at all?

NW: I see them as cohesively part of one body of work. I was a less experienced painter when I was making the erotica work. I started making it 12 years ago. I probably worked on that body of work for 5 years and learned quite a bit about how to put images and paintings together at that time. The current work is a synthesis of all that experience. We learn things as we go. Ideally, we get better at what we do. I actually have been making erotica paintings quietly in the studio. They're more interesting than the other ones because I know more about how to paint and how to use the materials. My ideas are slightly different–things develop and change.

MM: It seems like you have a knack for titles… “after school special”, “grassy knoll”, “back to nature”…

NW: They are all, for the most part, representative of queries I put into amateur porn sites that I got the images from. The “grassy knoll” is obviously the big question mark of how Kennedy was shot. “Back to nature” came up because I was sick at home from work and I had a box of oatmeal that said “back to nature” on it. I started laughing, plugged the words in, and came up with these hilarious videos from Germany of women rubbing their bodies against rocks and trees and fence posts. Everything came up in a very organic way.

Installation view courtesy of Fernberger Gallery.

MM: David Salle called you a “rare bird” and cited you as an artist who has reinvented realism in a way that both predecessors and contemporaries have not. How’d you receive this?

NW: That’s humbling. I mean, it's something I think we all aspire to…to live in the world, and to share our world with the world at the same time. I think that's nice. I should write that down.

MM: You should write that down.

NW: As a culture, we're constantly defining what's real. I watched a movie that was 10 years old yesterday and it looked so old to me. I have all these friends who are obsessed with this TV show called The Curse, and it has this really different aesthetic to it. It’s a different kind of light, a different kind of way of portraying people. People themselves haven't changed that much in the past 100 years in terms of how we look and how we are, but our portrayal of people has really changed and our way of looking has really changed. I'd say that our culture is constantly defining and redefining how we look and what we are.

MM: I think so too. It’s about ways of seeing.

NW: Ways of seeing and ways of portraying what we see and what we make.

MM: The ways of wanting to be seen have changed drastically too.

NW: Completely. Hopefully that gives more space.

Nicole Wittenberg, Pieces 2, 2024. Image courtesy of Fernberger Gallery.

MM: What are your aspirations for the future? Do you see yourself working in film or getting into that down the line?

NW: I've always been really interested in filmmaking. After art school I made a bunch of short films. I've been equally afraid of things that rely on collaboration for final output. And also things that rely on huge budgets. I feel like anything made in committee just requires so much compromise, and I'm not compromising. I don't like compromise and I don't think art is meant to compromise. I think the best examples of film in our culture have been when we had people with a strong viewpoint who were given a means to express that viewpoint with autonomy and authority, without having to compromise for budgetary reasons or other people's needs. I have a love of wanting to do film and I have a total fear of film.

MM: Painting reigns supreme in that sense. It’s a place you don't have to compromise.

NW: I don't have to compromise and I'm the only one in the room with the brush. I can take as long or as short as I want to, and it's done when I say it's done. That makes it incredibly scary but also incredibly powerful. Compromise leads to weaker things. When we get to see one strong viewpoint from a singular perspective, we can have a deeper and richer life experience that creates more space.

Jumpin’ at the Woodside is on view through March 16 @ Fernberger Gallery, 747 N Western Avenue, Los Angeles