Jingyi Li. The Hidden Drawer-Tea Spoon, 2024. 16x26x2.5cm, Bobbin Lace, antique tea spoon case.

interview by Lola Titilayo

At the center of feminist practice, soft-spoken materials, and Asian heritage, Jingyi Li is defining contemporary artistry through storytelling. Drawing on her PhD in anthropology, she weaves research, memory, and cultural narrative into delicate, hand-crafted lace and other tactile materials, transforming everyday objects into installations that explore emotion, identity, and history. From intimate cutlery sets in The Hidden Drawer to larger immersive works like The Oyster Pail, Li’s work unlocks the expressive potential of unconventional materials, creating spaces where Asian women’s stories are told.

LOLA TITILAYO: The Hidden Drawer places lace directly onto cutlery and vintage display cases. Can you walk me through the original idea for this series? Where did the first image or object come from?

JINGYI LI: The Hidden Drawer began with my interest in the ways women’s desires have been hidden, silenced, or disciplined throughout history. Across different cultures, women who expressed longing or sensuality were often labelled, shamed, or even punished — from moral condemnation to the symbolic “witch hunts” aimed at women who stepped outside prescribed boundaries. I wanted to create a space where these unspoken stories could surface quietly through objects that seem ordinary at first glance.

The objects came from an antique cutlery case I found while wandering through a market. I love spending time with old objects; they hold traces of the people who touched them, the gestures that shaped them, the lives they silently witnessed. When I looked at this case, I felt it could hold a story.

Jingyi Li. The Hidden Drawer-Butter Knife, 2024. 20.5x31.5x1cm, bobbin lace, antique butter knife case

TITILAYO: Lace is traditionally associated with feminine craft. Do you work with that history consciously? How do you position your hand-made lace work with your mission to build feminist space in your work?

LI: When I first discovered lace and the histories behind it, I felt as if I had fallen down a rabbit hole. Lace holds a long lineage of women’s labor that was often unnamed and overlooked, yet it carries a quiet depth. Working with lace feels like entering a dialogue with generations of women whose voices were rarely recorded, even though their hands shaped cultural traditions in lasting ways.

During my research, I came across the Lace in Context project led by Professor David Hopkin and Dr Nicolette Makovicky at Oxford. Their work brings together archives, textiles, and social history collections, and the online platform reveals an exceptional range of stories and research. It helped me understand how complex the cultural life of lace is far beyond decorative associations.

For me, lace is a material through which I can rethink what feminine space means today. I do not approach it as something fragile or merely ornamental. I use it to speak about desire, intimacy, and agency, and about the shifting experiences of being a woman. The process of making lace is central to this. The rhythm, the knots, and the tension in the thread all become part of the narrative. My body repeats gestures that many women have performed before me, yet I turn those gestures toward subjects that were often unspoken or hidden.

By placing lace in unexpected contexts such as cutlery, furniture, or sculptural forms, I try to create a feminist space where softness is understood as strength, and where femininity is allowed to move beyond narrow definitions. Lace becomes a language through which women’s experiences can be reconsidered and made visible once again.

TITILAYO: How do aspects of Asian cultural history, domestic rituals, textile work, and family traditions appear in your work, explicitly or implicitly?

LI: I grew up in a home where objects were never just objects. My parents collected everyday folk items from across China, so our living space felt more like a living archive than a typical household. There were stone mills once used to grind soybeans, delicate wooden moulds for printing cloth, herbal scales from old pharmacies, and hand-carved tools whose purposes I only learned much later. None of these things were valuable in a conventional sense, but each carried the wear of a long life.

As a child, I was drawn to these objects without fully understanding why. I would pick them up, test their weight, trace the surface of the wood, or smell the faint memory of herbs caught in the grain. Those textures became part of how I learned to look at the world. I realized that every mark or scratch hinted at someone’s gesture, someone’s labor, someone’s story.

This way of seeing stayed with me. When I began making art, I found myself returning to the quiet presence of old objects. They taught me to think of materials as companions rather than raw supplies, and to pay attention to the lives they have already lived. Working with antique boxes, cutlery, or textiles feels like a continuation of those early encounters. I am not simply choosing materials; I am entering a conversation that began long before me.

The influence of that childhood environment continues to shape my practice today. It bolstered my sensitivity to how objects hold memory, how they record everyday histories, and how they can reveal forms of intimacy rarely spoken aloud. In many ways, my work is an extension of that early fascination — a way of listening to the stories that quietly reside in the things we inherit, discover, or choose to keep close.

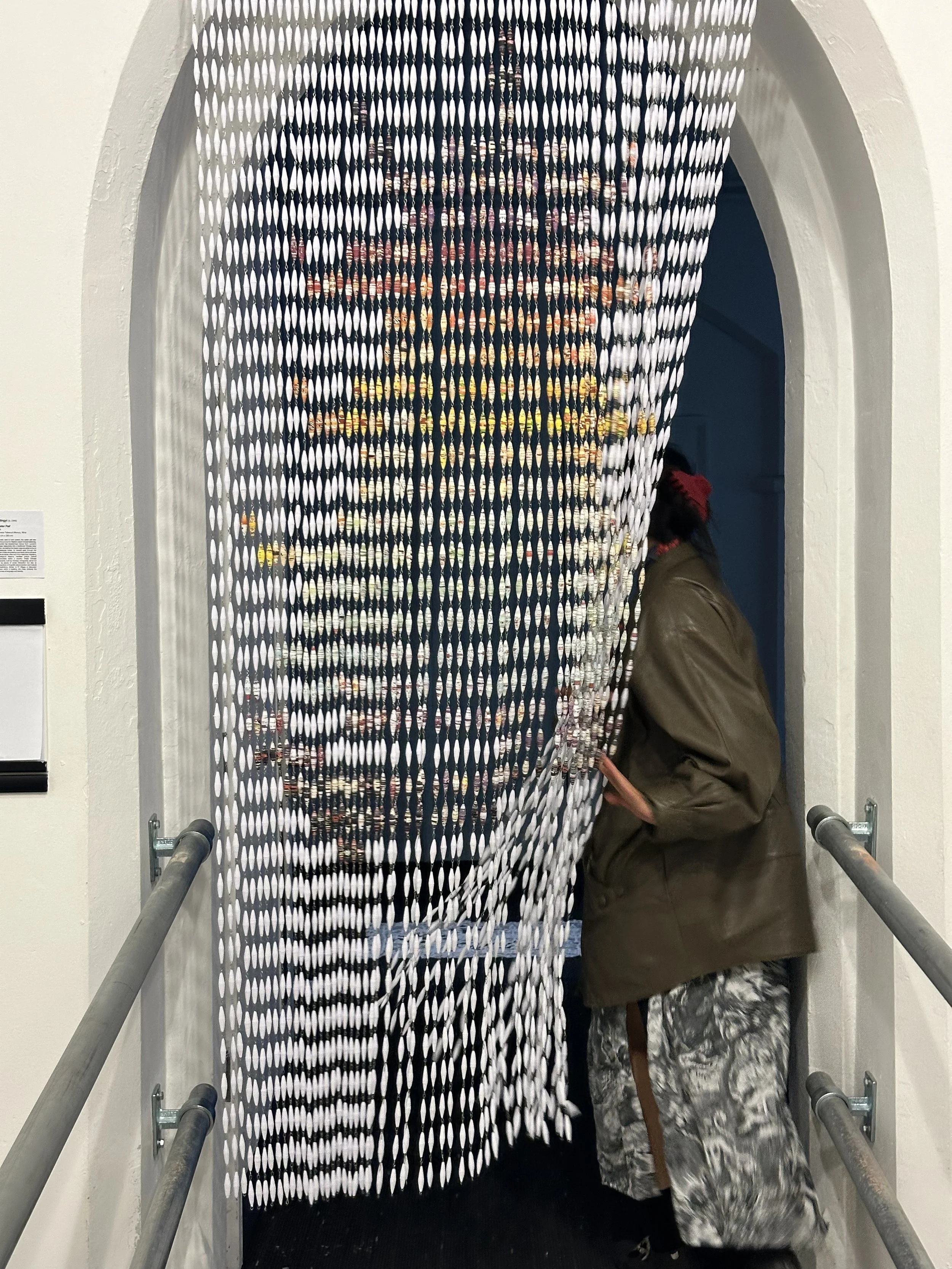

Jingyi Li. Oyster Pail, 2024. 110x280x1cm, Chinese takeaway menus, wire, paper

TITILAYO: The oyster pail carries strong cultural associations of migration and diaspora that are often translated simply as “Eastern cuisine” in a Western context. How does that history or symbolism influence what you are doing with it in this work?

LI: The oyster pail is widely recognized today as a container for Chinese takeout, yet its story is far more layered. It began as packaging for fresh oysters, but gradually became tied to a Western idea of “Chinese cuisine,” even though this style of food and its imagery were shaped outside China. For many people in the diaspora, the oyster pail carries memories of work, migration, and survival, especially for families who built their lives through small restaurants, takeaways, and other labor-intensive trades.

In my work, I draw on this history by transforming London’s Chinese takeaway menus into a beaded curtain that recreates the pagoda motif often printed on oyster pails. The curtain becomes an entryway into a symbolic enclave, pointing to the early Chinese communities that took root in London during the nineteenth century. These communities formed as sailors, workers, and migrants began to settle, creating businesses that offered familiarity and support in a new environment.

This curtain reflects how migrant communities build small cultural enclaves within a city. Chinese restaurants and Asian supermarkets often become more than businesses; they offer a sense of home and familiarity for people living between cultures. By recalling the imagery of the oyster pail, the work points to these modest yet meaningful spaces where identity is negotiated and sustained across generations. It also connects the everyday world of takeaway culture with the broader history of Chinese migration, showing how belonging and resilience continue to take shape even as a community’s visibility shifts over time.

TITILAYO: You’re also doing research in visual anthropology. How do academic research and studio practice inform each other for you?

LI: Anthropology has taught me to see objects in a different way. [Anthropologist] Igor Kopytoff proposes that objects have “cultural biographies,” and this idea goes beyond simply tracing where an object has been. It asks us to consider how objects move across social worlds, how they are classified or reclassified, and how each transition alters their meaning. This perspective shapes my approach to materials. When I work with antique objects, I do not see them as neutral supplies. I see them as objects whose earlier lives continue to resonate. Their presence becomes part of the work, and making with them feels like opening a new chapter in their biography.

My studio practice then becomes a way to think through questions that arise in my research. Through repetition, gesture, and touch, I come to understand craft in a bodily way, echoing what [anthropologist] Tim Ingold describes about making as a form of knowing. The hands often recognize something before the mind fully grasps it. Working with lace and soft materials turns ideas about labor, intimacy, and cultural memory into lived experience rather than abstract theory.

In that sense, the studio becomes a kind of field site, and the field becomes an extension of the studio. My PhD research examines how craft objects hold anthropological stories, and my practice helps me encounter those stories in a grounded and embodied way. The two processes move alongside each other, offering different pathways toward understanding how materials carry meaning.

TITILAYO: In the context of your broader practice, how does Marriage Story complement or contrast with works like The Hidden Drawer or The Yellow Vessel?

LI: Each of these works comes from a different stage of my life, and responds to different questions I was asking at the time. Marriage Story was made in 2021, when I was living in China and witnessing a strong wave of feminist awakening. Many troubling cases involving marriage and domestic violence were coming to public attention. The piece responds to that moment by revisiting rituals from traditional weddings. One example is “crossing the fire basin,” a custom meant to remove the misfortune supposedly carried by the bride. It reflects an enduring misogynistic belief about women’s inherent impurity. By using this familiar ritual, I reflect on the cultural expectations placed on women and the social pressures embedded in the idea of marriage.

The Yellow Vessel was created during my first year in London, when I was trying to understand how East Asian women are perceived within Western cultural frameworks and how stepping outside an Asian context can change how you see yourself. The work uses silk sculptures shaped like historical vessel forms, drawing attention to how the female body has been imagined, exoticized, or idealized through the male and imperial gaze. It parallels my own feminist consciousness developing alongside a new awareness of how culture shapes the perception of East Asian women, including the ways these views are sometimes internalized.

The Hidden Drawer is more introspective. It explores desire and interiority through antique boxes and lace, tracing a quieter process of self-discovery. Instead of responding directly to social events, it turns inward to consider personal memory and the private languages women create for themselves.

Together, these works map different moments in my growth, both as an artist and as a woman thinking through culture, identity, and change.

TITILAYO: As an artist exploring feminist space and Asian women’s stories, where do you hope your work will go next? What questions or ideas are you most excited to explore in the future?

LI: In 2026, I will join the Sarabande residency, a foundation established by Alexander McQueen to support emerging artists across disciplines. I will be surrounded by artists working in many different mediums, and being in that environment will certainly encourage me to think further about where my work can go and the stories I want to explore. Recently, I’ve been speaking with more women and collecting their personal stories. I am especially interested in the intimate and erotic narratives of Asian women, because these experiences are often shaped by stereotypes. By inviting women to speak on their own terms, I hope to make space for complexity, humor, vulnerability, and desire — feelings that rarely appear in public conversations about Asian femininity.

One encounter that influenced this direction came from a shibari [Japanese bondage] workshop I joined in London, followed by deeper conversations with the practitioner. She approached the practice through trust and emotional grounding rather than erotic display. She once described how she reframes bondage and BDSM relationships through a therapeutic lens, focusing on consent, communication, and the body’s capacity to release tension. When I experienced the practice myself, I realized how strongly the body can hold fear, longing, and memory. It made me think about how many stories sit quietly within women’s bodies, waiting for a language that feels safe.

Looking ahead, I want to explore desire as something shaped by culture yet deeply personal. Intimate stories reveal how women navigate identity and expectation, and they challenge the narrow roles often assigned to us. I hope my work can create more room for Asian women to speak about themselves with honesty, confidence, and complexity — on their own terms.