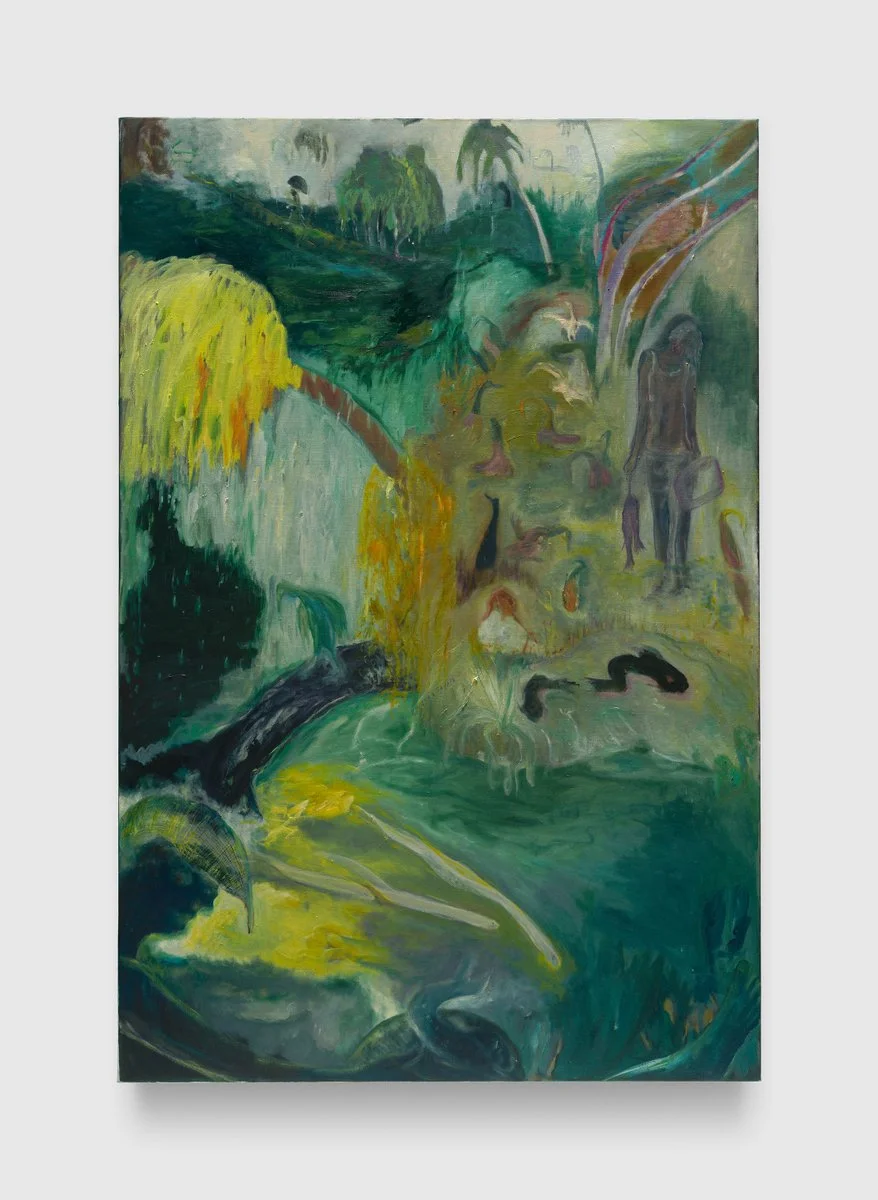

Sosa Joseph, Devil’s hour, by the river, 2025

interview by Alper Kurtul

Some landscapes are not merely seen, but remembered. In Sosa Joseph's canvases, rivers overflow, rain does not simply fall; it seeps into bodies, homes, and time. These paintings do not so much narrate the past as they establish a state of memory that revives it. Figures sometimes become distinct, sometimes fade; like memories, they oscillate between clinging and vanishing.

ALPER KURTUL: Standing in front of these paintings, I felt as if the river was remembering on my behalf. When you return to Parumala in your mind, what is the first sensation that comes back to you?

SOSA JOSEPH: Rivers remember—especially, I’ve read, where they used to flow. But I don’t know if the river I remember remembers me. In any case, when I “return in my mind” to the riverbank in Parumala, where I was born and raised, the first sensation that comes back is a sense of peace and contentment that feels very close to joy. I don’t think this is because my childhood and adolescence were free of privations, anxieties, or conflicts—there were many. But the setting made all the difference.

We lived right by the river, and much of my childhood was spent roaming the wilderness along its banks. I spent a great deal of time in the company of the river and the rain, as well as plants, birds, and animals along the shore. From an early age, I formed a sense of camaraderie with animals and plants. There was a kind of idyllic primitivism to those days, which now strikes me as blissful.

Even today, if I spot a squirrel in the park, or watch coots or ducks in London’s many water bodies, it sends me into raptures. I also seek out water—it calms me and makes me feel peaceful. However, one can return to that Parumala only in the mind. Urbanization has changed the place considerably: the swamps and wetlands were filled in, the swamp birds and animals are long gone, and the savage verdure largely lost. The river and the rain remain.

KURTUL: Many of your figures seem to hover between presence and disappearance. When you paint people from your past, are you trying to hold onto them, or let them go?

JOSEPH: Ephemeral—if I may say so—is the quality you’re pointing to: manifesting, then quickly fading away. But isn’t this a quality shared by most of what makes up our lives, or life itself? In a broader view of time, we are all transients—fleeting, fading apparitions. Holding on and letting go are two things we are constantly trying to do within our brief time here.

In the studio, however, when I paint—not just people, but also geography or setting—I can’t say whether I’m trying to hold on or let go. I don’t consciously plan to paint a particular person or place; they simply manifest on the canvas. A painting from the current exhibition that remembers my brother fishing in the rain is a case in point. I didn’t walk into the studio one morning deciding to paint my brother. The process is far more unconscious and spontaneous.

I often paint to see what is already in my head. As I push paint around, figures, activities, situations, and narratives begin to emerge—just like composition and colour. In this instance, I was simply trying to capture rain in a landscape. Through improvisation, a figure began to appear, followed by fish, and only much later did I realiZe it was my brother, fishing as he once did. In such an unconscious process, I can’t be sure of my motivations. So am I holding on, or letting go? I truly don’t know.

Sosa Joseph, Amma wants to finish singing before the flood drowns her, 2024-2025

KURTUL: Floods appear in your work not only as natural events but as emotional states. Is there a particular memory of water—its danger, its generosity—that still shapes the way you see the world?

JOSEPH: We loved rain and the river—especially rain over the river—but when it rained heavily and without pause, the river could rise and swallow our homes. And it did, quite often, during my childhood. Floods were common; some years we experienced more than one.

Not all floods were equal. Sometimes the river rose just enough to enter our homes like a timid, almost apologetic guest, occupying only a couple of feet from the floor for a few days. On those occasions, we tolerated its presence and carried on. We children were placed on tables or other high surfaces while adults navigated between these islands. From our perches, we watched the floodwater surround us. Driftwood floated in, sometimes with a snake wrapped around it; fish and frogs entered through the windows.

It made me realize that floods are great levelers. Humans, frogs, snakes, fish, wetland birds—we were all equally affected, disrupted, displaced. And then there were years when the waters rose much higher, submerging our homes almost entirely and forcing us into rehabilitation camps. I remember being evacuated to shelters run by the church or local administration, often schools converted into makeshift camps.

There is a painting in this exhibition that addresses such displacement and rehabilitation: Rain’s Refugees. So yes, this duality—nurturing and destructive at once—is something I’ve come to see as the essential nature not only of rain and rivers, but of most things in life.

KURTUL: I was struck by how women move through these paintings with a quiet authority, even when the scenes look chaotic. How do the women you grew up around continue to live in your work?

JOSEPH: I’m glad to hear that. I’ve painted women living in deeply patriarchal societies for some time now, and when I look at these works, I see it too: a certain silent authority—dignity is another word I would add—shared across these feminine figures.

Even while navigating repressive power structures, women in communities like ours held a great deal of authority, particularly within domestic and personal spaces. They resisted by choosing a middle path between open rebellion and total submission—silently subverting these systems while remaining, on the surface, compliant.

This quiet resistance, marked by subtle authority, was something I saw especially in my grandmother and my mother, but also in many working-class and lower-middle-class women I grew up around. The female figures in my paintings inherit not only this body language, but also the self-possession that comes with it.

Sosa Joseph, The rooster’s crows gave her nausea, 2025 (detail)

KURTUL: You paint from memory, not documentation. Does memory ever resist you—does it ever refuse to give you an image you need?

JOSEPH: Painting from memory suits my practice better. Memory, like imagination, isn’t entirely clear or concrete, and that lack of clarity leaves room for aesthetic interpretation. Photographs or direct observation can be restrictive, making departures from the real more difficult. Memory gives me just enough to work with, without overwhelming detail, and that freedom matters deeply to how I approach color, form, and texture.

That said, oblivion is as powerful a force as memory. Like a tattered tapestry, memory has holes that even imagination can’t fill. I might forget the structure of a flower or the anatomy of a fish or turtle. In those moments, I do turn to studies or reference material.

KURTUL: Your colors feel like weather systems, shifting moods on the brink of something. Do you think of color as something that happens to the painting, or something that emerges from inside it?

JOSEPH: I’m certainly not a painter who meticulously plans color. So yes—color happens. It emerges as I work.

I’ve come to think of color as a kind of music you listen to with your eyes — symphonies of light, in a sense. Some people create music through deep theoretical knowledge; others play by ear. I belong to the latter group. I don’t know much about color theory, and I resist generalizations. I move pigment around daily until I find the tints and shades that feel right.

KURTUL: Some scenes feel like they’re happening now and years ago at the same time. Do you experience time this way when you remember home?

JOSEPH: I wouldn’t say I experience time as non-linear, but memory does refuse to stay neatly in the past. Certain places and moments from home remain active in me—as sensations rather than stories. When they surface in painting, they tend to exist in a kind of present tense, which may explain why the scenes feel suspended between then and now.

KURTUL: In many works, the background feels as charged as the figures, almost like a witness. What does it mean for you when a landscape starts to behave like a character?

JOSEPH: A landscape only feels remarkable as a “character” if one assumes it is merely a backdrop. I don’t approach composition that way. The spaces my figures inhabit aren’t separate from them.

More broadly, I’ve always experienced plants, animals, weather, and geography as living—almost sentient—presences. I grew up talking to plants and animals, even reading to calves, as seen in Girl Reading to Her Buffaloes. I still anthropomorphize elements of nature.

So, when I paint a tree alongside human figures, I treat it with equal involvement. Humans, animals, plants, and the natural world carry equal weight for me—not just aesthetically, but spiritually.

Sosa Joseph, The rooster’s crows gave her nausea, 2025

KURTUL: Showing these deeply rooted memories in New York—so far from the river that shaped them—did it change the way you understand what the paintings hold?

JOSEPH: I think it’s important to clarify that I’m not showing my memories in New York. My memories matter only to me. What I’m showing are paintings that are incidentally based on memory. That distinction is crucial.

Art is not the same as its subject matter. The real content of a painting is the painting itself—not what it appears to depict or narrate. These works are often called autobiographical, which is partly true in terms of subject matter, but I was never interested in creating a painterly memoir or socio-cultural commentary. My motivation has always been formal: engaging with the aesthetic challenges of painting itself. Everything else is incidental.

Distance doesn’t change what the paintings hold. If anything, it tests whether viewers are willing to engage with painting on its own terms—beyond familiarity, narrative, or place.

KURTUL: Your canvases turn ordinary gestures into something tender, almost ceremonial. When you paint, how do you know that an everyday moment carries enough weight to stay?

JOSEPH: I don’t know in advance. I don’t curate moments from memory to paint. I simply paint, and as I do, moments arrive. Figures walk in. They evolve.

The everyday—the mundane, the banal—contains a great deal of quiet drama and theatrical potential. My task is simply to remain open to it.

Sosa Joseph