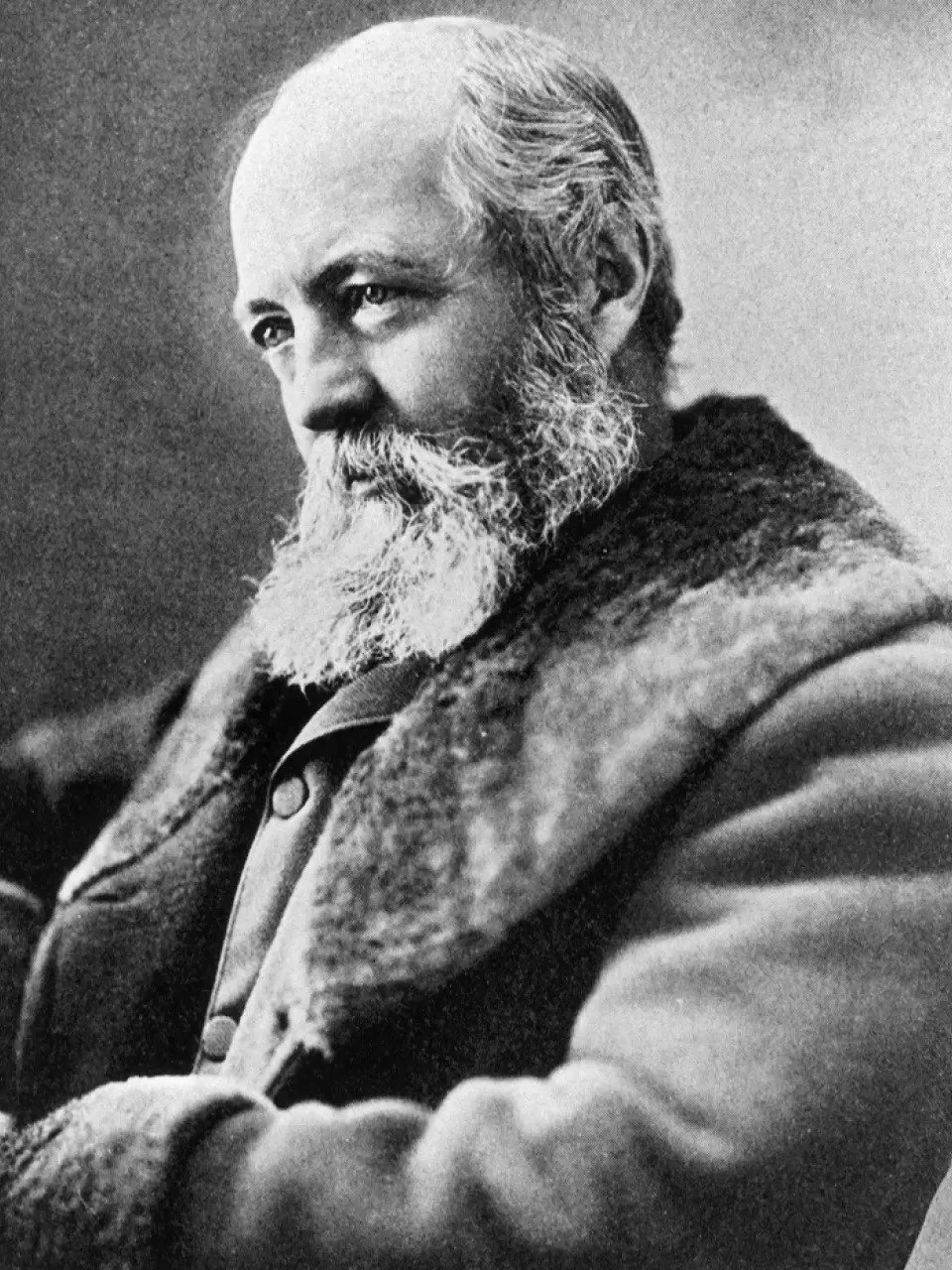

Frederick Law Olmsted

text by Perry Shimon

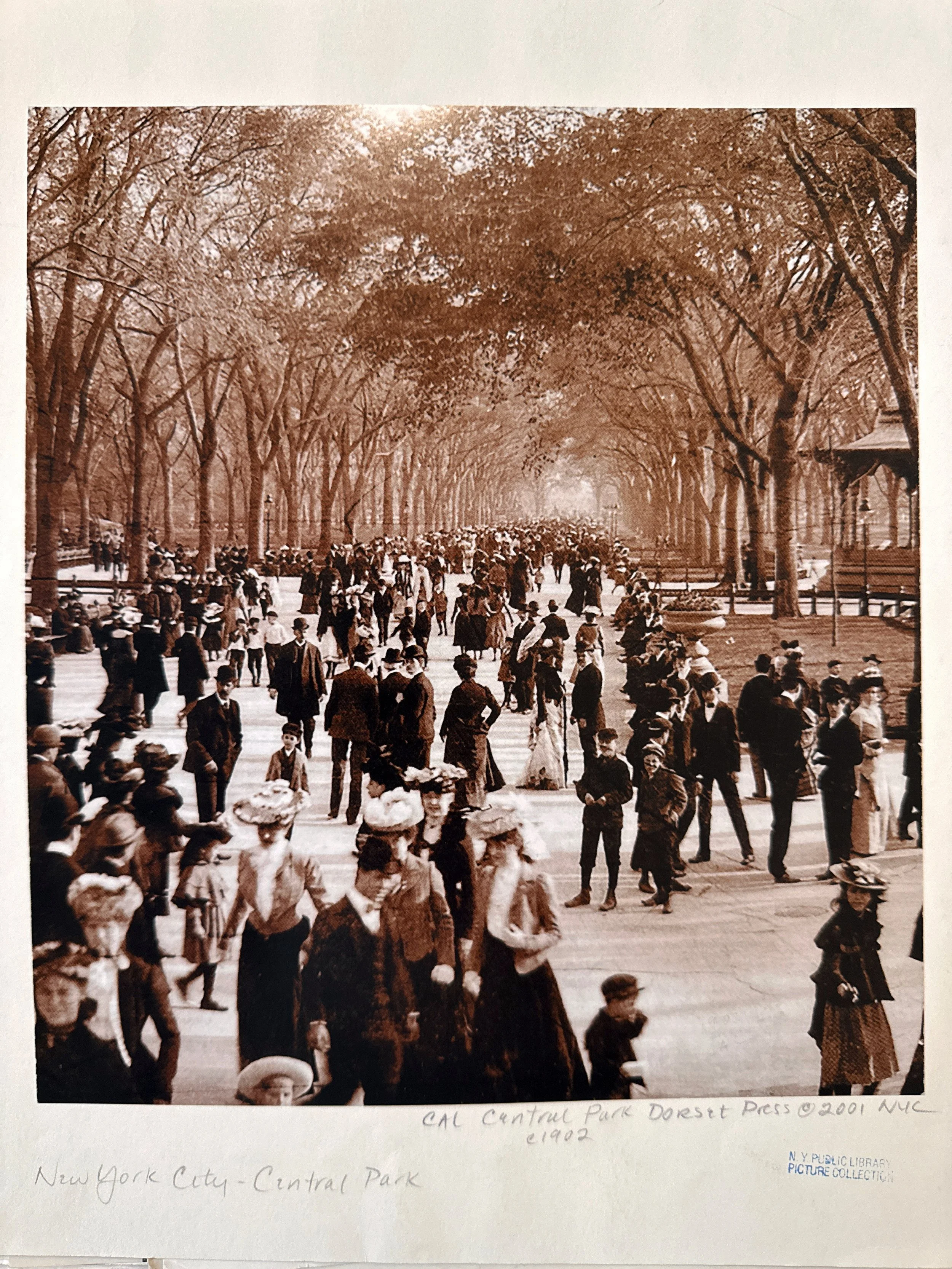

In the nineteenth century, Frederick Law Olmsted offered a distinctly North American adaptation of the English picturesque garden. Indebted to far eastern traditions and deployed at a scale in New York City perhaps without historical precedent, his progressive landscape architecture was realized with the explicitly democratic mandate of providing the most broadly accessible of public spaces. The Greensward Plan, later realized as Central Park and conceived with his longtime collaborator Calvert Vaux, marks a defining moment in world history and one of the most significant artistic interventions in the built environment in North America. He went on to design hundreds of parks, often collaboratively, and was largely responsible for founding Yosemite and the national parks movement.

Yosemite Valley by Aniket Deole via Unsplash

Olmsted’s approach emerged from reformist currents that included abolitionism, public health advocacy, sanitation reform, and early ecological thinking. Before turning to landscape architecture, he worked as a journalist and social critic, reporting on slavery in the American South and on the living conditions of the urban poor in northern cities. These experiences shaped his conviction that environments actively produce social life. Parks were not decorative amenities so much as infrastructural interventions, designed to counteract the physical and psychological damage of industrial labor, overcrowding, polluted air and water, and the accelerating velocity of capitalist urbanization. His landscapes were conceived as works operating at the levels of ecology and social space, and his work was concerned with the working classes rather than the elite.

New York Public Library Picture Collection

While it is impossible to fully separate Olmsted’s legacy from the general trajectory of Indigenous genocide, dispossession, and the manifold forms of subjugation and exploitation organized within the plantation and industrial imaginary, against these historical constraints, Olmsted fought for and won large, common, and beautiful spaces of ecological remediation, species diversity, and psychic restoration. His parks intervened directly in degraded urban sites, reworking hydrology, soil, and vegetation to produce more resilient systems. This ecological realism positioned Olmsted as an early practitioner of environmental design, anticipating concerns with biodiversity, stormwater management, and urban health.

New York Public Library Picture Collection

Also significant was his attention to circulation and movement. Olmsted advanced what we would now call multimodal design. Carriage drives, bicycle paths, and pedestrian walks were carefully separated by speed and use, allowing different publics to coexist with less friction. These systems emphasized gentle grades, curving paths, and continuous routes that connected disparate parts of the city. Movement through the landscape was slow, embodied, and immersive, oriented toward restoration rather than efficiency. Parks functioned as connective tissue, stitching neighborhoods together through shared green infrastructure.

Perhaps the trail, in a general sense—along with the mark—constitutes the basic grammar of art making: defining a frame and coordinates for apprehending the world and inviting its capacity for meaning.

Olmsted considered art without social utility to be ornamental and frivolous. His conception of art required a deep commitment to public use and dignity without sacrificing formal rigor or beauty. He was explicit that his parks were for those with the least access to leisure and health. Working people, immigrants, and the urban poor stood to benefit most, in his view, from fresh air, open space, and unstructured time. Parks were instruments of democratic leveling, spaces where social distinctions might soften through shared experience, and where physical and spiritual health were cultivated together.

These aspirations were never fully realized. In practice, Olmstedian parks frequently reproduced racial and class hierarchies even as they sought to alleviate their effects. The liberal claims to access masked structural inequalities determining who could safely and continuously use these landscapes. The creation of Central Park required the displacement of Seneca Village, a predominantly Black and Irish working-class community. Policing, behavioral codes, and informal norms often excluded Black residents, Indigenous people, and the poor from meaningful participation. Proximity to parks became a driver of real estate speculation and further displacement, transforming spaces nominally promoted as commons into engines of uneven development.

New York Public Library Picture Collection

Olmsted, operated in a palliative, pragmatic, political, and preservationist mode. He was an artist who conceived works intended for everyone and for the general health of urban regions that were otherwise destined for ruination by the narrow imperatives of capitalist accumulation. His thinking founded the discipline of landscape architecture, influenced generations of planners and architects, and his works have been enjoyed by millions, occasioning countless social and aesthetic encounters. Today, these parks, beloved and heavily used—though chronically underfunded and threatened by privatization—defend their existence through a limited liberal vocabulary of access, diversity, and quantifiable public health benefits.

The ongoing work of conservancies, friends groups, and community coalitions fighting for these spaces constitutes its own underexamined aesthetic practice. These formations operate within the same liberal logics that produce scarcity and enclosure, yet they enact a coalitional aesthetics of the liberal commons, rooted in maintenance, care, political negotiation, and collective presence. It is not incidental that Trump Tower borders Central Park, nor that similar quasicommons have driven patterns of displacement elsewhere. It’s a paradoxical aspect of ecosocial reform under liberal capitalism.

The picturesque terraforming of quasicommon space in a liberal society built on dispossession and exploitation can also be understood as a precursor to contemporary fantasies of space colonization, geoengineering, and green capitalism as enacted by an emerging planetary technocracy. These projects share an aesthetic vocabulary of rendering, modeling, fundraising, and speculative narration, along with an impulse to engineer nature at a planetary scale. In the longue durée, Olmstedian landscape architecture exists on a continuum that runs through European colonialism and plantation agriculture into modern parks to techno-utopian schemes.

Stanford Torus design proposed by NASA

Olmsted’s work, however, remains unresolved, more than exhausted. His parks persist as sites of protest, informal economies, subcultural gathering, artistic production, mutual aid, and provide a much-needed respite for the urban working classes—when they can free themselves from ever-increasing financial precarity and the expropriation of all their time and energy. For contemporary art, Olmsted marks a path not taken—or at least largely ignored—an art of collectively built and sustained infrastructure rather than individual possession: shared time more than speculative objecthood. The challenge is not so much to simply reproduce the Olmstedian park, but rather to grapple with its contradictions and extend the socioaesthetic project of the commons beyond the limits of liberal enclosure. A project that includes a revisiting of the largely erased practices of Indigenous Americans in the pre-Columbian period who maintained a greater equilibrium within their multispecies ecology. It remains to be seen what kinds of social and aesthetic projects will emerge to expand the liberal commons and perhaps transcend the extractive and growth-oriented systems that occasion it.

Otherwise is a series on neoliberal contemporary art and its unbounded remainders by Perry Shimon.

Otherwise Part VI