According to Neitzche, everything returns to the wheel of the cosmic process. At the beginning again, and again, you will find “every pain and every pleasure, every friend and every enemy, every hope and every error, every blade of grass and every ray of sunshine once more.” In this eternal cycle, great subversive seers and mystics, like Genesis Breyer P’Orridge, come around rarely. Her pain and her pleasure is a shared agony and ecstasy, which P-Orridge has ameliorated with her epiphany of the pandrogyne, from which the artist has escaped the bounds of either/or binaries into a more angelic, divine gender. Part shaman punk and part hermaphroditic angel, P-Orridge has been led by a series of these outer body visions. From the founding of COUM Transmissions, which challenged British society with blood-soaked performances and general anarchic disruption, to Throbbing Gristle, which brought industrial music into the modern lexicon, to the acid house of Psychic TV, to finally finding love in a dominatrix named Lady Jaye. On the occasion of her first solo exhibitions in Los Angeles, curator Hans Ulrich Obrist visits Genesis at home in New York, where she is fighting stage IV leukemia, to discuss her many life-altering epiphanies.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST How is your archive organized?

P-ORRIDGE Just over two years ago, I had complete kidney failure. My fiancé [Susana Atkins] is Spanish. She came here with a multiple-visit visa and I got sick just after we met. She looked after me because I had to have somebody with me all the time. The last time she came to New York, she organized all the photographs and put several thousands into sections, subjects, and separate little boxes and drawers. Now I can ring her up in Spain and say, “Where are the pics of Lady Jaye peeing in the street,” and she’s like, “Box #6 in the drawer on the left.” She knows where everything is, she has a totally photographic memory.

OBRIST Is your archive digitized?

P-ORRIDGE No, I don’t have any money to digitize. I don’t take grants; I have no income because I can’t do concerts.

OBRIST Can you tell me about some of your recent gallery shows?

P-ORRIDGE I had a show open last recently in Miami at the Nina Johnson Gallery that’s called Closer As Love. I don’t really take any notice to be honest, I’m more concerned with staying alive. I mean, it’s great that there’s interest. It reminds me of Derek Jarman when he was diagnosed with HIV. He said to me one day when we were sitting in his flat, “You know Gen, once they know you’ve got some kind of terminal illness, they’ll suddenly say they appreciate what you do.” And he said, “I’ve never had offers of money to make films like I’ve had since they knew I was dying.”

And then of course, as soon as everybody heard that I was potentially terminally ill, I get exhibitions and people suddenly say they appreciate my body of work, and I sort of think, “Well, thanks for telling me that forty years too late.”

OBRIST Well, I sort of think there’s some other reason. It has something to do with you anticipating what’s happening now in the world?

P-ORRIDGE [laughs] Yeah, of course. I’m being deliberately cynical. I just thought what Derek said was interesting. When I came back from the hospital last time, my editor—because I’m writing my autobiography, he said, “You’ll never believe this. While you were in the hospital I got a phone call from the New York Times wanting a quote for their obituary.” And I went, “Really?” He said, “Yeah it’s a bit weird, isn’t it? It’s already written and they’re just updating it whenever you’re sick to make it seem current.” So, they’re all waiting. There’s all these vultures waiting to go, “Oh, what a shame Gen died.” [laughs] It’s strange isn’t it?

OBRIST When did you have the pandrogyny epiphany?

P-ORRIDGE Apparently, in the ‘70s. Jarret [Earnest], who curated the show in Miami, found an old interview where I was talking about panthropology in the ‘70s, so it’s always been there in my mind as an ultimate theme. It was more about logic, observation, and considering human behavior. There seems to be what has sometimes been called original sin. There seems to be a flaw in human behavior. For example, how could there ever be a Second World War? We’ve maimed each other, killed people we love, destroyed things we like. Why would we do that? We could never do it again. That was stupid! But we do it again and again.

OBRIST It’s like Nietzsche’s eternal return.

P-ORRIDGE And so, I wanted to think, how could we change that? If there’s no either/or, there can’t be the other, and that can’t become the enemy because there is no other anymore. So, if the two become one there’s this divine unity.

OBRIST So, then you will have peace?

P-ORRIDGE Yeah.

OBRIST So, it was actually a peace movement in a way?

P-ORRIDGE Sure, I’m a child of the ‘60s.

OBRIST And how did you begin? Because last time we spoke, you told me that it kind of all began when you were fifteen, discovering Max Ernst.

P-ORRIDGE [laughs] Oh that was just the collages, really. The idea that you could take images of so-called “reality,” and then create one that never existed. This was an incredibly powerful aspect of creativity that sometimes is buried in commerce now. In fact, to me, art has always been spiritual. Always. And ultimately the art that really matters has to lead us towards the salvation of the species, otherwise what’s it telling us?

OBRIST How to fight extinction?

P-ORRIDGE Yeah, so I’m seeing these threads unfold more and more. I can remember when I was about eight or nine, watching my mother brush my sister’s long hair, and thinking, how come I can’t have long hair? And the answer was, because you’re a boy. So, at that point I saw that there was some misfiring in the logic. It was just an inherited, conditioned concept that didn’t make sense. And of course, as the ‘60s unfolded more and more, things that didn’t make sense, that were negative, were revealed and exposed for the insanity that they are. I’ve never changed my utopian view—that we have to work towards the species becoming one organism. No nations. No countries. No tribes. No either/or. No binary. We’re all human beings.

OBRIST So, it’s a very holistic idea?

P-ORRIDGE Absolutely. We truly are an artist who doesn’t just say that life and art are the same. From the very beginning, there has been no separation. That’s why I kept everything. That’s why I have an archive.

OBRIST Besides your autobiography, what books are you doing?

P-ORRIDGE We did a book on Brion Gysin that just came out.

OBRIST Brion Gysin brings things to your beginnings as well, because the other thing that seems so relevant in terms of your practice is this fluidity—painting, poetry, drawing, art, performance, music—you have so many dimensions. Poetry, as you told me last time we spoke, is quite at the beginning. And there are, of course, these two key influences, [William] Burroughs and Brion Gysin in validation of your entire creative and cultural engineering practice. How did you come to poetry, and why Burroughs and Gysin?

P-ORRIDGE I was at one of those horrible English private schools, I had a scholarship. It was called Solihull School. One day in English class, my English teacher said, “Stay behind after class.” And I thought, oh no. What have I done wrong? I must’ve got a bad mark on my essay. Then, he had this piece of paper, and he scribbled on it, “On The Road, Jack Kerouac,” and he said, “I really think you’ll appreciate this book. Try to find it.” My father used to travel a lot with his job, so I said to him, “Could you try and find this book when you’re driving around?” And one day he came home and he had a copy. He found it in a bargain bin on the motorway. And that changed everything again.

OBRIST On The Road was a bestseller then.

P-ORRIDGE It changed a lot of people I know from that era. But when I was reading it, what fascinated me about it was that it’s about real people. Although it’s written almost like a fiction, it’s real people. Who is Dean Moriarty? Who is Old Bull Lee? Who are they? I found out that one of them was William Burroughs. So then, I hitchhiked to London and went around all the old shops. I couldn’t find anything by William Burroughs back in ’65, ‘66. And then, I went to Soho, to the porno shops, and I remember I got Jean Genet and Henry Miller, because they were considered dirty books. And lo and behold they had Naked Lunch, since it had been prosecuted for being obscene. So, I bought the only copy, well actually I stole the only copy that they had. I read that and thought, wow, it’s a bit like Max Ernst. This is someone changing reality again. Reality isn’t linear. Time isn’t linear. It’s in a state of flux and chaos and again, the creative being has the ability, the right, and the opportunity to change reality. And that’s what I want to do because the reality I’m in isn’t one I enjoy. So, it’s a second liberation. For me, art is always about the big questions.

OBRIST Gerhard Richter says, “Art is the highest form of hope.” What would be your definition?

P-ORRIDGE Did he? Wow. I don’t have one because it’s always changing. I don’t think I’m on record as calling myself an artist or a musician. I have said I’m a writer, and I love to write, but it’s shamanic to me. I always say this to people at lectures, “What’s the first book of the Bible? Genesis. But what’s the other title of that book? The Book of Creation. What does that mean?” The first thing god does is create. That means creation is holy work. So, to be an artist or creator is to be using divine systems to get closer to a purer reality, and a divine perception of existence to go as deep as you can.

OBRIST It’s interesting, your first mentioned public appearance starts with Throbbing Gristle, but you did things long before.

P-ORRIDGE Oh, fuck yeah.

OBRIST So, when was the first public appearance of your work?

P-ORRIGE 1965. It was a street performance. I’m a great believer in not just sitting and complaining, but taking action. So, at this private school, we came up with this idea—I’d discovered Japanese haiku. We wrote lots of different words on cards by hand, and then on a Saturday, with two or three friends, we went around the town, which was a really horrible, sterile, suburban place, and we left them in the gutters, ashtrays, waste bins, just on the floor. We made this beautiful litter, and the idea was that people picked it up thinking, what’s this? They were accidentally writing a poem. It was written about in the local paper, then it got mentioned on BBC radio, and then I was asked to give talks at the local church.

OBRIST It’s interesting that you then became part of collectives of groups. How did COUM begin?

P-ORRIDGE We’d left the Exploding Galaxy, David Medalla’s project, and decided to hitchhike around London. So, I went and saw my parents. They moved to a town near Wales named Shrewsbury and they just started their own business. I said I’d help in the office typing invoices and stuff, and one day I went with them for a drive through Wales. I was in the back of the car and it was a sunny day. I had my head on the window of the car, I closed my eyes, and then all of a sudden, I was next to the car. My consciousness was flying along next to the car. But, it was passing through the hedges, nothing actually blocked me, I could penetrate the physical world. That happened for about twenty minutes, or so. All the while, I was hearing voices, seeing images and symbols, and one of them was ‘Cosmic Organicism of the Universal Molecular,’ and ‘transmission.’ COUM Transmissions. When I got home, I wrote everything I could remember down.

OBRIST These were all written as text?

P-ORRIDGE Scribbled in notebooks. Some of them still exist. One of the words we received was cosmosis.

OBRIST Like cosmos and osmosis.

P-ORRIDGE Exactly, and it was the positive transfer of energy from one being into another, like in a plant, but between beings. That the whole universe was smaller, and smaller, and smaller particles until there were no particles. In a way, it was a precursor to quantum physics, though I didn’t know anything about quantum physics. And so, I felt that not only was it this true epiphany, but that it was my lifelong task, my mission, to proselytize the core ideas of that for the rest of my life.

OBRIST It was like a manifesto?

P-ORRIDGE Yeah.

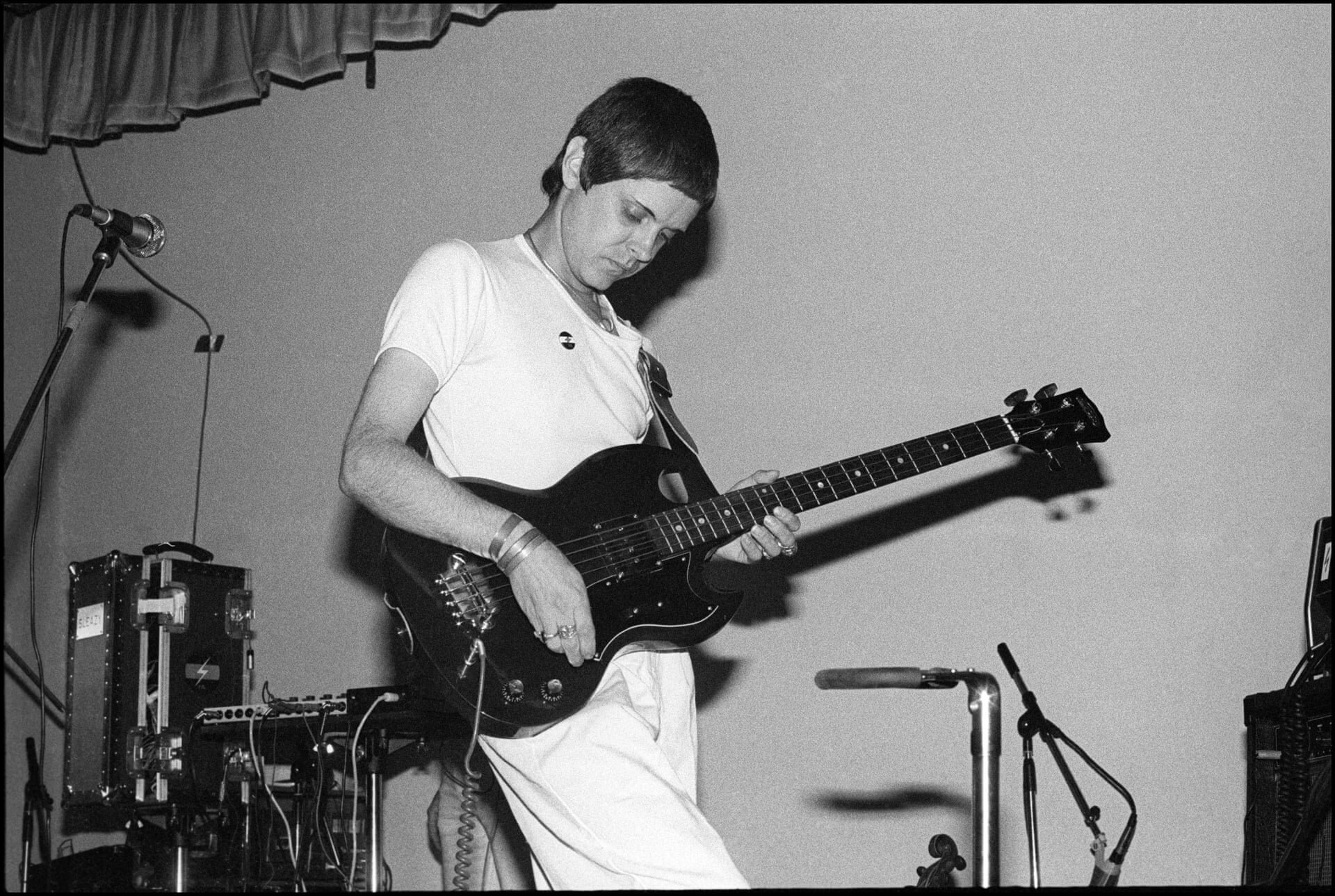

OBRIST What was the epiphany of Throbbing Gristle?

P-ORRIDGE Oh, there wasn’t one. That was just logic, and observation, and deduction. I was looking at music and thinking, god I haven’t bought any records for two or three years, and why haven’t I? Because it’s not satisfying. It’s not teaching me something I didn’t know. So what am I gonna do? I guess I have to make music that does satisfy me. Because that’s the COUM approach: if it’s not there, then make it.

With music it was: What is music? Music is sounds. There’s no good or bad sounds, there’s just sounds. What is a rhythm? Something that happens at least twice. That’s it, that’s all it is. What do we got that we can make sounds with? We looked around our basement and we had a broken bass guitar, an old violin, and an old drum kit. We bought a guitar from Woolworth’s for 15 pounds, and Cosey said, “It’s too heavy.” So, we sawed off the extra wood and asked, “How’s that?” and she said, “Much better.” Chris Carter built his own synthesizers, Sleazy was totally into tape recorder experiments à la Burroughs, and I was really into writing lyrics that were based on love stories and rhythm and blues, American rock, and so on. Something that was English and about my experience in post-war Manchester. By process of reduction, you end up with what’s left and go, that’s what we have.

OBRIST The best producer is a reducer.

P-ORRIDGE Yes, of course. When I was once asked to remix “Test Dept,” because they were having real problems, I went and erased all but three tracks and it was fine. Throbbing Gristle was very much conceived in the same structural way. Then, I thought it has to have a name that has nothing to do with the history of rock music. I thought factory because of Andy Warhol, but that’s too obvious. I was talking to my friend Monty and he goes, “Gen you keep saying the word industrial. You keep saying industrial this, and industrial that.”

OBRIST It’s a very Manchester word.

P-ORRIDGE Yeah, of course. I was talking about the factories in Manchester and all the steam trains being cut up when they were obsolete. So, I went, oh yeah, it’s industrial music. That was September 3, 1975. Then, it was a matter of convincing the rest of the world that what we were doing was a really good idea. [laughs]

OBRIST There was another epiphany in ’81, and that’s Psychic TV.

P-ORRIDGE Yeah, that was towards the end of COUM Transmissions. I’d started having, for lack of a better term, shamanic, out-of-body experiences. I’d been speaking in tongues. I’d been having astral travel where I’d lose my body completely, and I was in other dimensions; as if I’d taken psychedelics, but I hadn’t. It had gotten so intense that I thought, I can’t do this in public anymore, but I do still want to explore this. So, I started to explore those rituals in private.

OBRIST Rituals are important because Tarkovsky said, “We live in a time bereft of rituals and we need to reintroduce rituals,” and you’ve done that a lot.

P-ORRIDGE Absolutely. They’re always there in my life. From ‘75, when we started Throbbing Gristle, COUM was still going on, but in private. By ‘81, I didn’t want to do Throbbing Gristle anymore and we stopped. I thought we saw it out, proved we could invent a genre of music, and convinced the fucking world that it’s a good idea. So, why do it anymore? What else is there to do? Our fans are really into Throbbing Gristle, and they dress like us, and they write to us, share stories about their life. What would happen if a group took that as raw material? Thinking, we’re like you too, what can we do together? Through conversations with Monte Cazzaza and Sleazy, we developed my idea of Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth.

OBRIST Yeah, that’s very relevant because Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth is of course a hybrid. It’s a fan club, a ritual, a cult. Bodily fluids played a role, didn’t they?

P-ORRIDGE [Laughs] Well, we sat there—myself and Sleazy—and said, “We need a ritual.” Through my exploration of Austin Osman Spare and other rituals I’d been doing, I knew that the orgasm was the key. That at the moment of orgasm, all the different layers of consciousness are all linked up for a moment. The juice of orgasm, whether it’s male or female. And then hair. We liked the idea that those are all the things that, normally in magic, you’re not supposed to let anyone else have. So, we got people to send them to us as an act of trust.

OBRIST You also recently went from 2D to 3D. Can you tell me about your shoe sculptures?

P-ORRIDGE Oh, the shoes. Yeah, I love making shoe sculptures. We were making them just for fun. All the shoes belonged to sex workers, strippers, dominatrices, hookers, and topless go-go dancers. In those black boxes are a lot of little materials—we keep them sometimes for twenty years before they have a purpose. The crystals are from the chandelier of Lady Jaye’s grandmother who died. Everything is connected to life.

OBRIST Tomorrow is the tenth anniversary of Lady Jaye’s passing. How did you meet?

P-ORRIDGE We met in a dungeon. A friend of mine, Terrence Sellers, had a dungeon on 23rd Street and a little apartment off to one side. When we came to New York, we would stay there. So, I’d been out with Debbie Harry and Chris Stein at this club called Jackie 60, and I’d done a load of ecstasy. Those were the days when it was still legal, still pure. It was three in the morning and I didn’t want to wake up Terrence, so I went in the dungeon, put a sheet over me, and went to sleep. That’s what Lady Jaye saw when she came to work. She was a dominatrix there. She thought I went back to sleep but I didn’t. I was in the dark. I was watching this doorway and the other room was lit, and she was walking back and forth in what we knew straightaway was a real 60’s outfit and a Brian Jones bob. Then she started to get undressed and put on fetish clothing. Out loud I said, and I felt embarrassed saying it because it so was not like me, but I said, “Dear Universe, if I can be with that woman that’s all I want for the rest of my life.”

OBRIST Oh wow, you knew immediately. She was a nurse too, right?

P-ORRIDGE Yeah, she was a nurse as well. She was fascinated with the human body, it’s limitations, and the fact that it’s really just a lump of meat, of material. She said, “It’s a cheap suitcase that carries around our consciousness.” One of her other great sayings was, “See a cliff, jump off.” She was truly fearless. We’ve never met anyone so truly fearless about everything and anything.

OBRIST When did you decide on the idea of your bodies becoming one? Because it’s so important now, how did this epiphany happen?

P-ORRIDGE It turns out that it began in the ‘80s, in terms of the theory. It’s the same problem of the either/or, a universe that has an either/or is malfunctioning. And it seems very likely that the whole point of existence is to return to unification, divine union, a realization of similarity. The first thing Lady Jaye did before she took me out was dress me in her clothes, put makeup on me, and decorate my hair with jewels. We said to each other, “I wish I could consume you. I wish I could just literally hold you, and we would melt into each other, and become one.” It was that true, unconditional, infinite desire that is inexplicable but incredible. We thought about why we feel that way, why we’re so desperately in need of becoming each other, or at least becoming one more? We thought of Burroughs and Gysin, as always, and The Third Mind. When they wrote and did cut-ups together, they weren’t by William or Brion, but the product of a third mind, this other being. We thought, what if we cut ourselves up, and became one new being? And that’s the pandrogyne.

OBRIST Lady Jaye had surgery on the chin to match you?

P-ORRIDGE And the nose and under her eyes.

OBRIST And you took hormones but it didn’t work out?

P-ORRIDGE Yeah. She took male hormones and it made her aggressive, and we took female hormones and it made me cry all the time. [Laughs] We said, “At least we can say now to some degree we do understand the monthly effect of the hormones shifting.” It’s really odd when you suddenly cry over nothing, and feel shattered and upset. So, what we did was shave off all our body hair, so we were newborn babies, and for the first part of that day we wore diapers as well. Hair contains time, and people can take a piece of hair and figure out what drugs you’ve had, and certain things that have happened to you. We wanted to start fresh, so we became babies.

OBRIST Twins.

P-ORRIDGE Little twins, yes. Then we started looking for confirmation in the myths and cultures of the world.

OBRIST Because hormones didn’t work, you went into ketamine? Why did ketamine work better than hormones?

P-ORRIDGE Who knows why it worked for us? Different things work for different people. But over two years, we did it every day. In fact, we would load a needle up and put it at each side of the bed, and whoever woke up first would inject you while you were still asleep, so you would wake up high on ketamine. We would do it all day and we learned how to navigate it. We didn’t do huge amounts so we were completely lost...

OBRIST Do you have any unrealized projects? Dreams?

P-ORRIDGE Yes. We’d really like to set up a COUM collective. Not a commune, but where each person who’s deeply involved has their own yurt, or whatever, and then a main building that’s a resource for archives and technology, workshops and so on. It’s a think tank for alternatives.

OBRIST And what’s your advice to a young artist?

P-ORRIDGE Don’t try to have a career. Be creative. Be a creator.

OBRIST The exhibition in Los Angeles was called Pandrogyny 1 and 2?

P-ORRIDGE For two locations. One at Tom of Finland, and the other at Lethal Amounts. At the Tom of Finland house, they keep it as it was when he lived there. When you do an exhibition, what you put there goes amongst all his things, so that one is mainly sculptures. It has things like “Tongue Kiss,” which is two wolf heads, and the tongues have been replaced with knife blades.

OBRIST It’s crazy that this was your first show in LA. What’s your relationship to the city?

P-ORRIDGE I never had one really. I would never live there. To me, it has a strange atmosphere. It’s like it has a big cave underneath, with a dark energy in it that you can fall into by mistake. It doesn’t suit me at all. Mainly the art world has tried to ignore us for years. It’s really important for young artists to step away from that and look at examples of mail art and chapbooks.

OBRIST Generosity?

P-ORRIDGE And generosity. Sharing. Roxy who was just here, a young artist and musician, she said that she’s always amazed how by generous I am, giving things away. And I say, “Well, what am I supposed to do with it, hoard it? To what end?”

OBRIST That’s a very important motto for the new decade.

P-ORRIDGE Sharing and generosity. Absolutely.