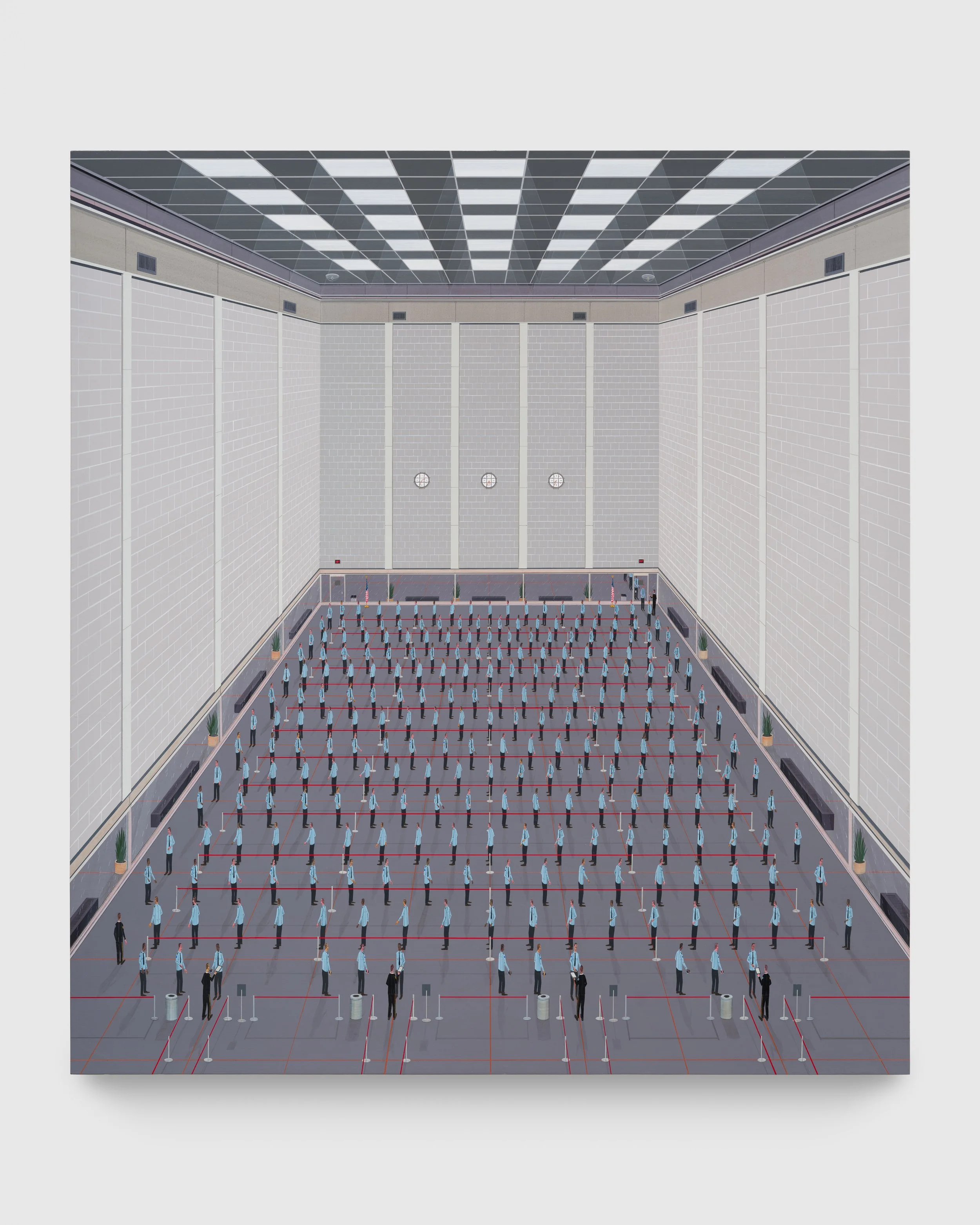

Ian Davis, Agenda, 2022. Photo: Ed Mumford. Copyright: the artist. Courtesy Galerie Judin, Berlin.

interview by Mia Milosevic

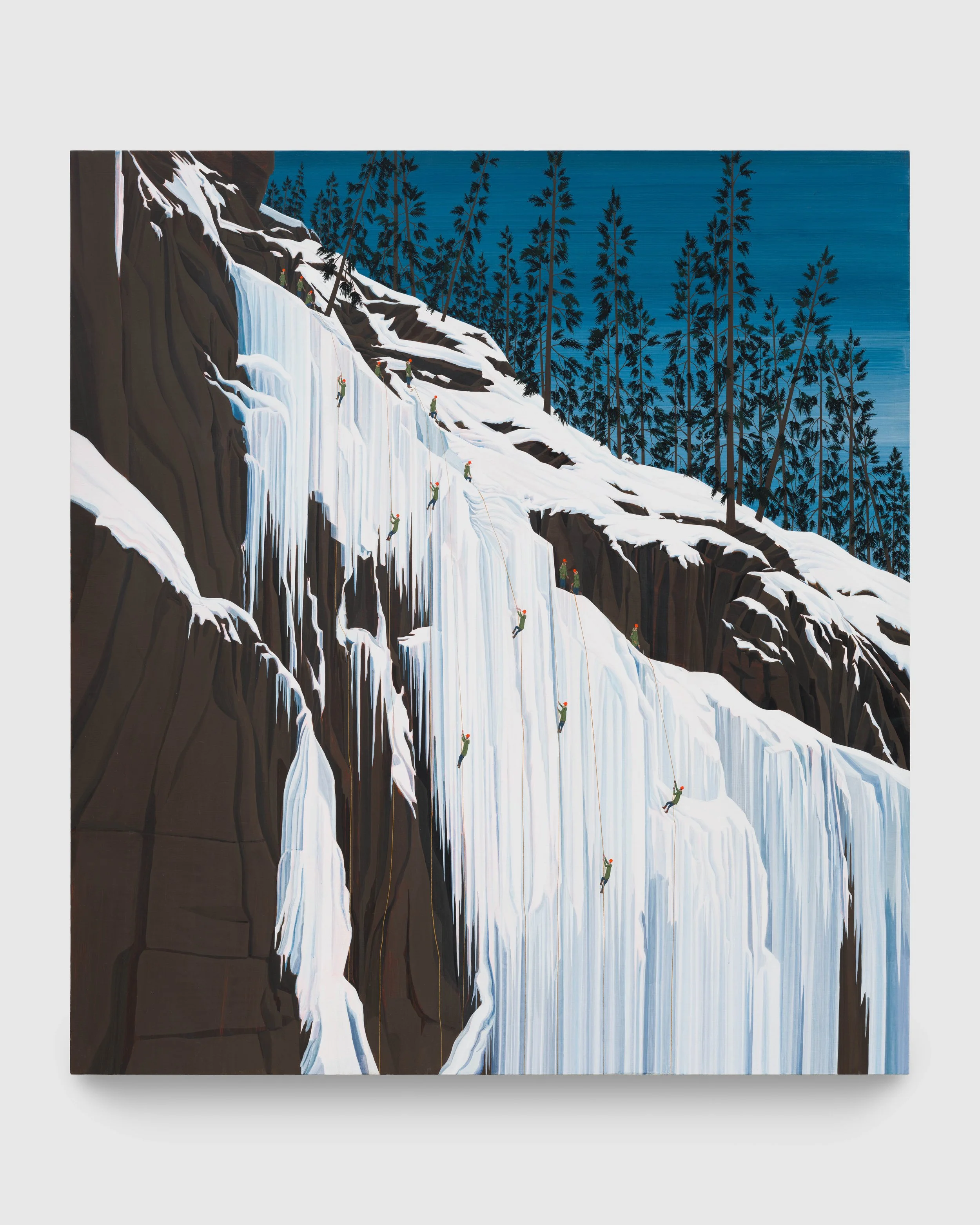

Connoisseurs of world order fill Ian Davis’s canvases, their picturesque and surreal stomping grounds an ode to both beauty and horror. The eeriness of his hyper-structured displays is overlaid by a rhythmic attitude and hip-hop influence. Davis’s landscapes keep a certain distance from the scenes they portray—the viewer is implicated at altitude, surveying a scene as you might an out-of-body experience. The entrapments of the modern day—wealth, power, surveillance—are articulated by a contemporary rendition of art history’s revered flâneurs. Starting with a blank canvas and a commitment to an idea, Davis’s process is completely inseparable from his final product, which are both uniquely his own.

MIA MILOSEVIC: How did you get into art initially, and what brought you into your distinct style?

IAN DAVIS: I got into art the way a lot of people do. I grew up in the Midwest, so I didn't have a ton of exposure to fine art, but I did travel with family. I had grandparents that would take my brother and me to Europe once we got into high school, so I started looking at art. I could always draw though, and people just said, “You're an artist, draw this.” Growing up in Indianapolis, I didn't think of artists as being a job that anybody really had, I didn't know any. So then I went to college in Arizona 'cause I didn't know what a good art school was (laughs). While I was in Arizona, the last year I was in college in the mid-to-early nineties, I saw Jean-Michel Basquiat's work, which wasn't like everywhere at that point—they didn't make like skis and backpacks and t-shirts. I had known his name from hip-hop music 'cause I was big into music, but I didn't know him as an artist. When I saw his work, it was the first time I really related to the way a painting was made. All my paintings were very influenced by him and Philip Guston and Max Beckmann and kind of sloppy figurative paintings—and people were buying my paintings, so I didn't have to get a job. It was cheap to live in Arizona, so I kind of drifted through college, not really knowing what I wanted to do.

There was a retrospective of Basquiat’s work at the Brooklyn Museum in 2005, I think. When I walked in and saw these things I was like, Jesus, I knew exactly how they were made. I just realized I had internalized them so much that while I was there I was like, I gotta do something else. Like this isn’t me, I'm not doing my thing at all. So I decided I wanted to start making paintings that weren’t expressionistic, but instead very controlled—retaining some of the repetitive, rhythmic qualities of Basquiat’s work. I kept all these compositional things that I learned from him, but started making them in a really methodical, slow way. That's when I started to really paint the way that I paint now—this really hypercontrolled, repetitive kind of thing.

MILOSEVIC: Does music still have an influence on your work?

DAVIS: Yeah, I mean I like art but music to me has always just been more direct—it just hits me. I’m just more fascinated by music. It just does things to me that art doesn't usually, it can go with you anywhere and it doesn't have all the trappings of the art world. I don't make music so I can just enjoy it, I suppose.

MILOSEVIC: Are there musicians that you feel like you could point to that influence your work, like aesthetically?

DAVIS: Yeah, for sure. I think a lot of music that I like is very sort of repetitious and minimal, like The Fall or Can, or a lot of reggae, I like a lot of jazz stuff like Fela Kuti, just things that sound like interlocking patterns. I think that's what I feel like relates to my work—a lot of my paintings are just a huge series of complicated patterns that are laid on top of one another. I think I like a lot of what that kinda music is doing because it’s what I feel like I'm trying to do with my paintings.

MILOSEVIC: In your artnet interview from a few years ago, in reference to the people you paint, you said, “You know how you hear about a person getting mugged in broad daylight and nobody does anything about it? Sometimes I think I’m painting all those people who didn't do anything.” Could you elaborate on that?

DAVIS: It's funny, I don't remember saying that. I mean, a lot of times the people that are in my paintings aren't really doing anything. And if they are, it's not really clear what they're doing. Like, there's a formal element that they're there for, which is for scale, et cetera. But I think in terms of the meaning of the people, they're not participating—I can't say that for all of them—but usually when they are doing something, I don't want it to be very clear what they're doing. And even if it is clear what they're doing, why they are doing it isn't clear. So, there's a kind of nonsense to it all. I guess maybe that's what I meant, even if the paintings are about some problem, the people aren't really helping. It's a pretty dim view of humanity, I think (laughs).

MILOSEVIC: In terms of the perspective that you use for a lot of your work, is there a strategy behind it?

DAVIS: I suppose it depends on the painting, but I guess it should be said, I don't really plan them. I kind of figure 'em out while I'm making them. Obviously I'm attracted to a very symmetrical composition a lot of times, especially with the architecture paintings, it's sort of cobbled together. Like it's correct enough that it's not meant to look off, but a lot of times I think about the way a picture can move your eye around. I also think a lot about trying to make a thing that will look striking and interesting from a distance, but then when you get in close to it, there's a lot to examine both with what's painted and how it's painted.

I like this idea of really clearly and plainly trying to describe something that doesn't really add up or make sense. It's like the bits of a narrative, but I don't have a narrative in mind necessarily. And if I do, I'll realize why I'm making it or what it means while I'm making it. I'm just sort of following formal, allegorical or symbolic notions of giving something a feeling.

MILOSEVIC: Your recent show at Nicodim was called “God’s Eye View.” Did you come up with the title?

DAVIS: They asked me for a title and I was having a hard time. Titles to me are always either just there, or I have to search through scraps of paper that I write things down on that could maybe be a title. Usually if I have to come up with one, 'cause somebody's asking me for one, my mind goes blank. Ben from Nicodim called me and said, how about “God's eye view?” And I said, “Oh, that's pretty interesting.” He said, “Well, it's something you said when we were at your studio.” So yeah, I guess it was my idea, but I wouldn't have thought of it.

MILOSEVIC: It seems like your style has stayed pretty similar maybe since that experience in the Brooklyn Museum and deciding what you were going to paint from then on. Do you feel like your process has changed? Like, not necessarily what paint you use, but your mindset and how you choose your content?

DAVIS: Yeah, because when I first started making them, I couldn't paint very well that way. So they were kind of clunky and I was focused more on the painting than what they were about. I mean, the ideas in them have remained fairly consistent. I think that the kinds of things they're talking about, like wealth and power, are still topics that I'm preoccupied with. That stuff was there even when my work looked like Basquiat, Philip Guston, Max Beckmann hybrids, but I can just paint so much better now. It's kind of subconscious, you just gather techniques that work for what you're doing. I try not to get too concerned about being efficient—there's definitely a quicker way to make a painting like this.

You could plan it and make a digital image and project it and lay it out and do it a lot more directly, but to me, figuring it out as I go and not knowing exactly what I'm making is kind of the reason I'm doing it. I'm sure there’s an easier way for me to do it, but I just figured out some inefficient way. I'm trying not to use technology (laughs).

MILOSEVIC: Do you enjoy the process of not having your paintings pre-planned?

DAVIS: Yeah, because I don't want to make something I've already seen. There has to be something in it for me because—I enjoy painting obviously, it's like the only thing I do—but it's also a lot. It takes a lot. It's a lot of labor. Especially filling in huge areas of people or whatever, it all has to correspond with everything around it. It’s never just like mindlessly filling in. I have to pay attention to all this stuff while I'm doing it. And also try not to like, smear my sleeve across a part of the painting that has wet paint on it and then have to figure out how to fix it (laughs). There's a lot of days where I'm just sitting with one brush, one color, painting one thing over and over and over all day long. And that's kind of a drag, but I think that that's how my paintings end up being what they are.

MILOSEVIC: In terms of the repetition, how do you go about that? Are you trying to be meditative or is the process meditative at all? Are you trying to create that effect visually?

DAVIS: Yeah, it's great when that happens, when you lose track of time, but a lot of times I'm considering so many things spatially and keeping everything in line. I have tricks I can use to do that, but it's rare that I can just shut my brain off and it'll all be laid out correctly. It takes a long time to start something. By the end I'm working on top of a framework that's already there, so it's easier for me to work out how everything will correspond. It’s fun to start them and it's fun to finish them, but the middle is a slog—especially with a larger painting.

I had a big painting in my show at Nicodim, it was a huge airplane painting, huge for me at least, and the whole time I was just like, well, I'm painting this airplane. I didn’t know why I was painting it the whole time I was doing it. What was the purpose of it? I painted this airplane with all these branches and plants sort of framing it. And I was just like, this isn't enough. But then I kind of just ignored it for a few months, and when I brought it back out and looked at it, I realized that was the point. You can't tell if it's taking off or landing. And there's a lot of different ideas suggested in that—is it going up or down? I just need to have a reason to do things and sometimes I don't know until the end.

MILOSEVIC: Do you feel like you enjoyed your expressionist painting more, or are you drawn more to the visual order that you paint now?

DAVIS: It’s fun to make a painting that takes a couple days or a few hours, but those weren't really my paintings, they didn't really feel like they were mine. I knew I was just learning how to build a painting. But, I'm not like an orderly person. That's the thing. Like this obsessiveness—I'm not like this outside of painting. Obviously it's part of my nature to be this way, but also sometimes I wonder if it's like, I'm from the Midwest and I have to show people that I can really work hard or something. Like I have to prove to whoever, maybe myself, that I can really make a painting and this is the way I'm doing it.

It wasn't my plan to turn into this, it just sort of developed. I should say though, that in terms of the meanings of the paintings, what's been strange in the last 10 years is that I felt like they used to be speculative. Like some of the paintings were just sort of me being afraid that something could happen. There's this quality of anticipation about them, like something bad is about to happen. I feel like reality has moved so much closer to the thing I'm describing or the world I'm painting, and it's a bit confusing. It's been a bit confusing over the last several years because I feel like I don't want these to feel too topical. I also don't want them to feel too on the nose, you know?

MILOSEVIC: Do you have thoughts about taking your work in another direction?

DAVIS: I don't have fantasies about doing something totally different. I do have temptations to make abstract paintings, I would love to make some abstract paintings, but I feel like there's endless things I could do with the way I'm painting. And if it did change, it wouldn't be because I had some eureka moment that changed it, it would be because I’d want to deal with some kind of subject, so the painting would be dictated by the change in subject matter, if that makes sense. The idea is primary over the way the idea is conveyed. I have something I want to paint and everything else follows—I'll find out how and why while I'm doing it.

MILOSEVIC: What was your process like when you did that cover for The New York Times?

DAVIS: The Times contacted me and needed a cover the following week—it took like four days of haggling over what I was gonna do. It was their idea to portray a bunch of people standing around the White House. But it was my sketches, like they picked one of the sketches I made. And then I made this really little painting because I just didn't have enough time to make a painting the way I would do it. So it didn't feel like my work really. It was a marathon getting that thing done. That felt really different. But it was great to have done a Times magazine cover 'cause however many million copies of that were printed. Ideally it would've been one of my paintings that everybody saw, or everybody who looks at The New York Times.

MILOSEVIC: Do you think about surveillance when you're making your work? Is that a fear or is it just something that comes out naturally when you're dealing with the content of your work?

DAVIS: Yeah, definitely. Even to the point where I've put surveillance cameras in them, because the viewer is implicated, but not in there. But it's probably a bit broader than that. It's probably more a fear of technology or the unknown. I don't want to emphasize it too much, but the view of humanity I'm describing is fairly dark. Surveillance cameras are just part of the modern landscape but they're also one of the only things I put in my paintings that would put them in the present day. It's a reminder of a lot of different things, I think. And they can also be hidden away in a painting the same way they're hidden away in the world. Like you ever look around, especially in New York, and you're like, God, it's cameras all around all the time and it's like when the hell did that happen—it's a bit of paranoia and there's a lot of anxiety. There's a lot of anxiety in my paintings.

MILOSEVIC: That's interesting 'cause I feel like your work is super meditative in a way, but there is some anxiety, so the contrast is interesting.

DAVIS: It’s funny because I think that that's really what the repetitions are. Because I literally just do this. Every day I'm here doing this. So whatever is in me is in there from day to day. And some days are very anxious and some days aren’t, and I'm also just dealing with the limit of what my hands can do. Some of the things I'm painting are so tiny and detailed—you can paint the same shape 400 times, but it's never going to be exactly the same. You start to notice even in huge fields of repetitions, all these weird little variations that just occur—'cause I'm a not a machine, you know. I'm kind of treating myself like one, but can't be one.