interview and portraits by Summer Bowie

Brianna Mims is a polymath if I’ve ever seen one. Along with a lifetime of training in myriad dance forms and becoming a multidisciplinary movement artist, she can likely be found speaking publicly on the role of the NAACP and transformational justice in the abolitionist movement, or walking runway at any number of fashion weeks, or developing curriculum for children to feel safe in moving and communicating freely. Then again, she might just be researching the efficacy of our local welfare system, or brushing up on her Arabic. When she’s done with all of it, she takes a step back and acts as a facilitator who intricately creates a neural network of every last disparate interest by assigning it to the appropriate person within her community. She is currently an organizer-in-residence at the Women’s Center For Creative Work, and her current project, Letters from the Etui is an amalgam of art, abolition, education, and support. It is a tender space where the carceral state can be felt, both at home and abroad.

SUMMER BOWIE: You describe yourself as an artist, facilitator, and abolitionist. Do you feel like the order of those labels matters at all, or are you equally all of them?

BRIANNA MIMS: The order of the labels do not matter. They all feed one another.

BOWIE: You don’t seem to compartmentalize your work at all. Can you talk about the way that you prioritize the balance between art and policy reform?

MIMS: The art that I make that’s overtly political is cultural work. It’s about shifting culture alongside policy so that we are creating sustainable change. Most of the work includes a direct call to action on a policy level. However, it is important to me to create various access points to the conversations because the work isn't merely political. It's personal, interpersonal, cultural, and spiritual.

BOWIE: How did you personally become connected to the work that you do? On the artistic and political sides?

MIMS: Artistically, when I joined the Justice-LA Creative Action team. I learned how to marry both sides of myself and I had the chance to learn from and build with people while doing so. My work in the policy realm is simply a result of my understanding for the need for change on the policy level. What happens on a policy level and within the abolition theory/scholar space really informs my art.

BOWIE: What is the Sarah’s Foundation?

MIMS: It is a program I started at the Salvation Army in Jacksonville, FL when I was in high school. I used to volunteer at the center with my mom and one day I noticed a lot of new residents that were children. I offered to teach a dance class to the children on Saturdays and it grew into a program that included dance, tutoring, and mentoring. The program continued for a couple of years when I left FL and moved to LA. The dance class that I was teaching developed over time into a movement and self-reflection class; It became a bit more rooted in somatics and conversation. I have taught this class for various time frames in Philadelphia for Resources for Human Development and in LA at Union Rescue Mission, Malabar Elementary, Crete Academy, and Santa Fe Springs Correctional Facility.

BOWIE: That really speaks to your emphasis on creating various access points. There’s a phrase you seem to resonate with about touching everything and holding nothing. Can you explain what that means to you?

MIMS: Yes! Many people have recently been asking me about that exact phrase!!! The quote came from the book Instinct by TD Jakes. I read it when I was in high school and was really moved by it. I attended a talk he had about and he began talking about the keys to his success. If you don’t know, TD Jakes is typically known as a pastor, however, he wears many hats that expand across many different fields and has built an empire. He said the key to his success was his ability to juggle in a multitude of jungles. He said in order for him to do that he had to “touch everything, and hold nothing.” At that time in my life, I only considered myself a dancer and I was defined by what that meant, by what my career was supposed to look like...dance company..or commercial route. When reading the book I began to acknowledge there were parts of myself that I wasn’t nourishing: gifts, skills, talents. So when hearing that quote I committed to not being defined by being a dancer and to nurturing all of my skills, gifts, and talents. At that time, I didn't even know if I had other gifts. For me, that quote has layered meanings. My relationship to it changes by the season. I love to continuously unpack it. Right now, it is a reminder to listen and honor the wisdom of my instincts. It is also a reminder to listen for when to let go. This can be physically letting go of something, but it's also about not holding on to the idea of what I think something is supposed to be; especially in regards to the work I create, or this idea of who I am, or what I’m capable of doing. I often say a lot of the time my work evolves outside of me because once I let what needs to come through me flow, the project is outside of me and I have to let it go and be what it is supposed to be.

BOWIE: Speaking of projects, what is the #jailbeddrop series, and how did you get involved?

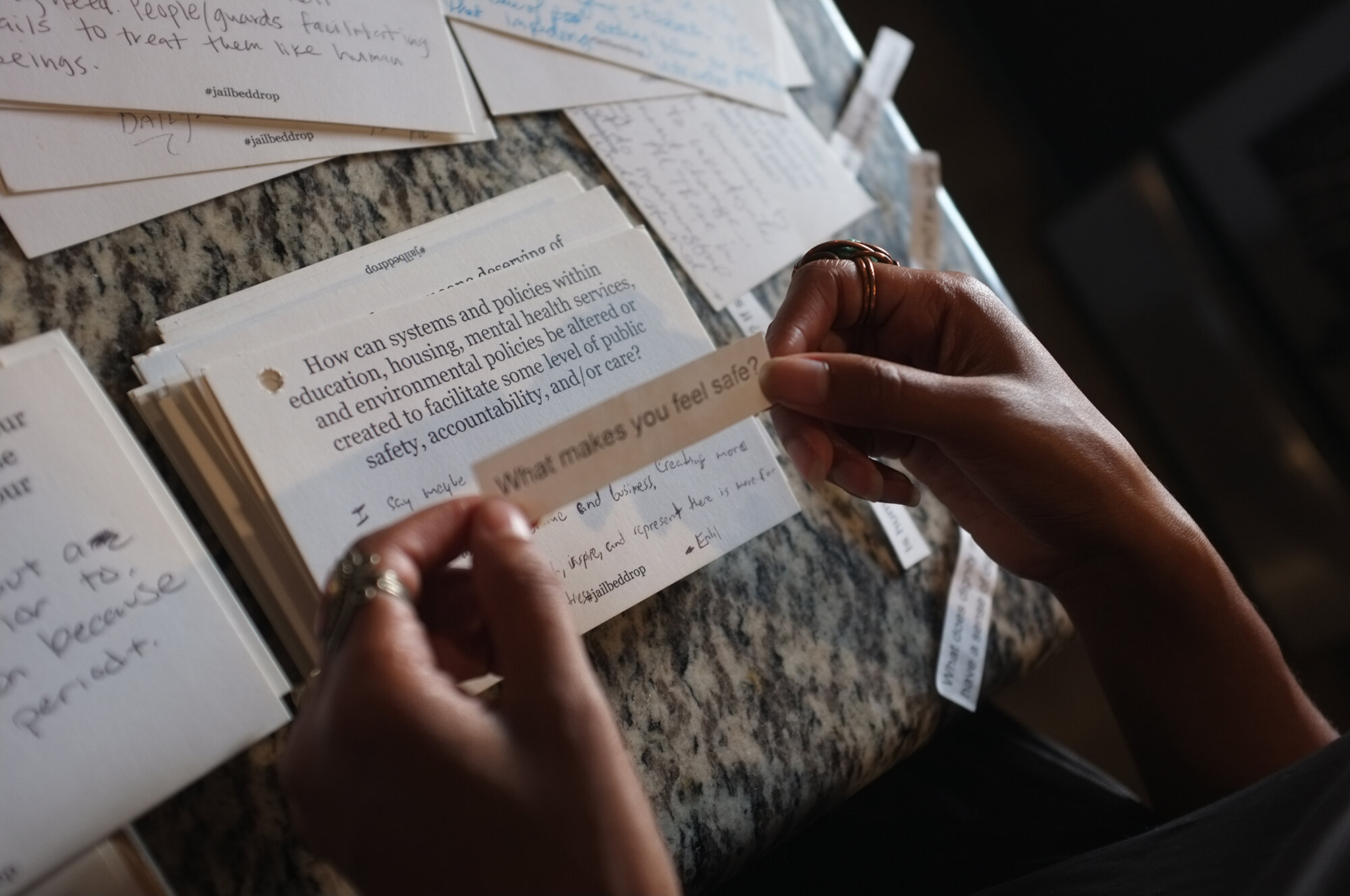

MIMS: #jailbeddrop was started by Patrisse Cullors and Cecilia Sweet-Coll through Justice-LA. It began as an art series to support the initiatives of the organization. The first one happened in September of 2017. They put 100 jail beds in front of the LA Board of Supervisors office. For the second major drop, fifty artists were given a jail bed. We all created pieces of various mediums and the day before Christmas in 2017 at the same time, we activated different cities within Los Angeles County. I was in Manhattan Beach with my collaborator Jullian Grandberry and we shared a movement meditation piece. After those major drops, there were several smaller drops and I was unconsciously building upon ideas that would later turn into the performance and installation that has been touring LA. For my senior project at USC, I wanted to expand on the movement piece that I had shared in 2017, so I put out an artist call at the university. I knew that I wanted to work with architecture students so I had a friend reach out to them separately. That's how Minh-Han, Georgina, Bindhu, and Adam joined the project. I knew I wanted the architectural installation to be interactive. However, I didn’t know exactly what that looked like… and I think this is where the concept of “touching everything, holding nothing” comes back into play in the way I led. I had to trust all of my collaborators' individual knowledge and skill sets to really contribute what they were supposed to, not merely what I imagined them to do… It’s always interesting to find that balance between letting go of my idea of what I think they are supposed to do and guiding them so that the work is aligned. The first year we did the project we supported Measure R, it was our call to action. The work has grown so much since the first iteration at CAAM and we have shared the work at many places in LA. I’m very grateful.

BOWIE: How was the Letters from the Etui project originally conceived?

MIMS: The last #jailbeddrop, which was the first time the project had an entire gallery space, included a series of workshops. A professor at Cal State LA attended one of the talks and reached out to me afterwards about a video series he curated with his students. The animated shorts that are featured in Letters From the Etui are from a collaboration Professor Kamran Afary led with his students at Lancaster State Prison and animation students at Cal State LA. The videos were supposed to be displayed in a gallery at Cal State LA, but due to COVID, it could no longer happen. So, he handed the videos over to us to present. I didn't know how to present them, so I had them for a while before the concept developed.

Then, Mandy Harris Williams from the Women's Center for Creative Work reached out to me about an organizer in residency program. She asked if I had any ideas around anything I wanted to create/organize and I had a couple, however, they could only facilitate things that were happening online; so the video series was my only option. Mandy said that we could present them on their own website and that some sort of programming should also happen. Those were my starting points. Once I began to organize the workshops and get the bios from the folks inside, it started to move on its own. It was really hard for us to come up with the name. We sat on the phone for hours brainstorming and nothing was coming up. It wasn’t until I had the idea to create merch to raise money for folks that are currently incarcerated that things began to make sense to me.

As I was thinking about what we could sell, I was opposed to creating t-shirts and tote bags. We ended up deciding to create and sell envelopes in a very beautiful way. I was thinking about things that were relevant right now and I started thinking about the things people hoarded at the beginning of quarantine and the whole vote by mail drama that was happening. I had a lot of very bizarre ideas like selling eyelashes! After talking with my team, envelopes stuck. I asked Han to draw some sketches for an envelope series and she suggested I reach out to one of the #jailbeddrop artists we’ve worked with in the past. I called Chris and he loved the idea. He told me that when he was incarcerated he used to draw on his envelopes and the folks on the outside would sell the envelopes and send the money back to him. Once the prison found out he was making money this way, they banned him from being able to send out envelopes with drawings on them. That was the moment of confirmation for me. We further discussed the significance of letter writing for incarcerated folks. I took this information back to my team for our name brainstorming process. We finally came across the word Etui via Hans' roommate. An etui is a small box where you keep very small and precious items. The word is derived from its old french root word ‘estui’ which means prison. Again, the work was moving on its own. It gets even better, Dr. Afary referred me to one of his family members to do a workshop, Frieda Afary. She does a lot of abolition work in North Africa and the Middle East. When I got on the phone with her she mentioned that she had been translating letters from Iranian political prisoners into English. As we talked more about the concept of the project and the significance of letter writing to system impacted folks, we thought the letters would bring a very important layer to the conversation of letter writing apropos system impacted folks.

BOWIE: We often talk about the effects of incarceration on the incarcerated, but what does it mean to be system impacted?

MIMS: I define system impacted people as folks who are currently incarcerated, formerly incarcerated, and the loved ones of those who are or have been incarcerated.

BOWIE: When you talk about creating a safe and tender space, I can really feel that in the way that tenderness plays a role in the act of letter writing. What is it about this form of communication that is so important?

MIMS: Yes, what you witness in Letters From the Etui is the various ways letter writing is used: to connect with loved ones, to self reflect, to advocate for yourself or others, etc. For incarcerated folks, for a long time, this was their main form of communication. For many folks inside, it still is their main form of communication. It holds a different kind of significance when you have been away from folks for so long and you don’t know when you’ll be able to see them again. For me, letter writing is very precious because you can really take your time and be intentional with your words, it's also easier to communicate hard things because you are not in a live conversation and seeing the other person's immediate reaction, and it is something that you can keep forever.

BOWIE: The workshop series component to the project also encompasses a lot of different topics, from current propositions on the ballot related to prison reform (J, 17, 20), to #metoo behind bars, to somatics and wellness. On a personal level, which of the workshops are you looking forward to the most, and why?

MIMS: I am personally looking forward to Prentis Hemphill’s workshop and Frieda Afary’s workshop. I am obsessed with Prentis’ work and I have never attended any of their workshops so I am excited to learn from them firsthand. In regards to Frieda’s workshop, I am super excited to learn about the abolition work that is happening in North Africa and the Middle East. In my studies around the carceral state in the US, I have learned about the connections to the carceral system here and the occupation in Palestine. I have been studying the occupation and learning Arabic. I began learning Arabic before I learned about the connections between the systems and have continued to do so. I love finding the cultural, historical, and present through lines between the regions in my studies.

BOWIE: It seems like the disciplines you explore are limitless. It’s like a kaleidoscopic constellation of connections that you make. Who are some of the artists and activists who inspire the work that you do?

MIMS: d. Sabela Grimes, Patrisse Cullors, Maytha Al Hassen, Jade Curtis, Moncell Durden, Jessica Litwak…these are the people that first come to mind.

BOWIE: From your vantage point, what are the strengths of the artistic communities within Los Angeles?

MIMS: The fact that a lot of the artistic communities that I am a part of are very communal in the way in which they work. I have and have watched so many other artists get things done with very little resources. The artists here really work as a family. However, artists need funding!!!

BOWIE: Yes! This is essential if we want to keep germinating more ideas and more culture. Are there any other future projects you can talk about in the works?

MIMS: Yes, I have so many ideas right now!! I am finishing up a film that I have been working on with Giselle Bonilla. This project is very different from my previous works. It is really just me doing whatever I want. It’s an experimental film. However, for me, it doesn’t seem disconnected from my work because I really believe we have to include the conversation of play and pleasure into our abolitionist frameworks. Play and pleasure as a guide for strategy… play being the highest form of research. Play and pleasure as a personal guide. I read Pleasure Activism by Adrienne Maree Brown recently and she talks about the knowledge and guidance that comes from leaning into our desires and the erotic. We also have to prioritize play and pleasure as things that are essential to our well-being and not something we have to work tirelessly to deserve. And this film is just me playing and leaning into desires that bring me joy...like setting my tits on fire.

Follow Brianna Mims on instagram @bj_mims and go to lettersfromtheetui.com to learn more about the project. Sign up for their online workshop series: Oct 22, Nov 5, & Nov 21