James Spooner. Photography: Moses Berkson, courtesy The Broad:

ED PATUTO: I wondered if you could talk a little bit more about the anti-establishment quality of the scene back then in the East village and Basquiat's work, and about how artists almost avoided mainstream success or money because it meant selling out. I was a dancer back in those days, and I just got tired of being broke. And also my parents said, “Listen, you have to go to college, because we're not going to help you anymore.” But it was definitely a Bohemian lifestyle.

JAMES SPOONER: I grew up in the DIY punk scene and I carried not only the ideals, but I was also trying to figure out how to “adult” with those ideals. I was basically on my own after high school. My first solution was to live in a squat where I only had to come up with like $60 a month to pay like the gas bill, and I dumpster dived. But when you're part of the community, it feels very normal. And then, a few years later, quite by accident, I found myself throwing parties and that turned into DJing. Party promoting gave me a way to make art all day and be out at parties, and just have the time of my life. And even with Afro-Punk, I screened the film and then that led to doing events, which eventually led to the Afro-Punk festival. But once the festival became more focused on catering to corporate sponsors, that's when I bailed. But it's always the question of like, how can I both make art, make money and not fuck anybody over along the way? Basquiat is interesting because you can hear him lashing out at various corporate interests, but then there's another side of him that very much wanted to be famous, very much wanted to make money. And interestingly that fame and money may have been the demise of him.

ED PATUTO: People ask me frequently, why has Basquiat endured? Why is he so relevant and so popular right now? A big part of it was what you’re speaking about now, in terms of really representing a lifestyle that was a challenge to the mainstream. He was very, very political. He made paintings like Irony of Negro Policemen. Or Beef Ribs, Longhorn which is in The Broad collection, that addresses commodities made by Black bodies, and labor, and the exploitation of Black bodies to produce all these products. And also Defacement, which was about Michael Stewart's killings at the hands of police for being a graffiti artist. Tagging was a crime in New York and you often heard of graffiti artists being armed with the spray can. Basquiat, through his paintings, was drawing attention to these kinds of issues that we are still dealing with today.

JAMES SPOONER: These issues within the Black community haven't changed. I also think Basquiat is celebrated in the kind of way that we celebrate basketball players or hip hop MCs that come from the streets, because again, we have this young man who became wealthy and famous, like almost overnight. And that's the dream: we've got this young, attractive guy, who's got his finger on the pulse of this electric city and he's making really smart work, and people are celebrating it both in the underground and the mainstream, which is very rare. Usually the mainstream catches onto things much later. And by the time they do, they've watered it down and disfigured it to a point where the originators don't recognize it anymore, but somehow Basquiat slid through and was able to do his thing authentically. I think for many young, Black kids seeing somebody make it is like, oh, well that gives me permission to dream.

ED PATUTO: With Basquiat, it’s the way he went from painting to his band, Gray, that was a No Wave band, to DJing. I mean, he DJs in Blondie's video for "Rapture" and DJed in clubs, including the Mudd Club downtown. He holds a relevancy that many people seek to have today, and very few people can really attain it.

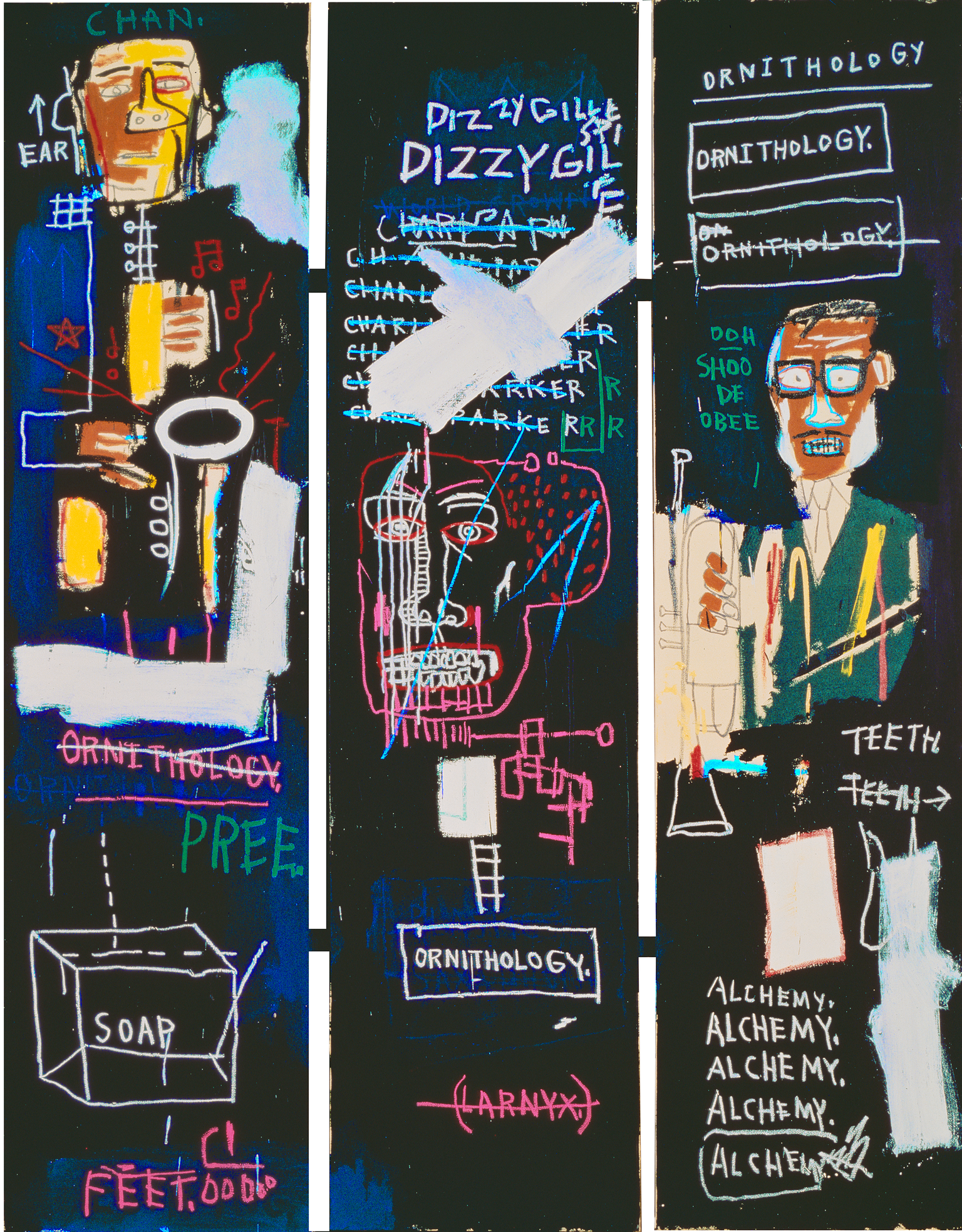

Jean-Michel Basquiat, With Strings Two , 1983. A crylic and oilstick on canvas . 96 x 60 in. The Br oad Art Foundation. © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

JAMES SPOONER: I think I was really trying to capture that energy at the Summer Happenings at The Broad in 2017, which I helped curate.

ED PATUTO: The Summer Happenings were really a way of giving people many different ways to experience contemporary art and consider the creative process of artists. When an artist is working, they're listening to music in their studio and they’re thinking about what's going on in the world. The Happenings were really designed to give a fluidity to the visual arts.

JAMES SPOONER: That was a great event we did for Basquiat. I was excited to reach out to all of these different avenues of non-visual art. We brought out The Downtown Boys and Zebra Katz. And then, you know, I thought about the nightclub aspect of Basquiat's life and we set up a punk and hip hop DJ soundclash in one of the rooms in The Broad. And we had DJ Rashida who is known as Prince's DJ and Michael Stock, who does the long-running Punky Reggae Party and Part-Time Punks in Los Angeles. Another huge highlight was Shani Crowe who is known as a hair artist. She does insane braiding art. We were trying to figure out how you can do that as a performance piece? And she was like, “Well, I've thought about braiding my hair into a whip and then whipping this white guy. What do you think about that?” I thought it was going to be a performance, but she actually whipped this guy with her hair.

ED PATUTO: I have to say that was a phenomenal expression of her anger because she did that simultaneously with a video of people from the community being interviewed after white cops had killed Black kids in their neighborhood, and they were acquitted.

JAMES SPOONER: I think that one of the most essential parts of the No Wave moment, as it relates to Basquiat, is that it's this real DIY moment. You can learn how to play as you're performing it, and a lot of punk rockers take that for granted. In the seventies, you had to be like a virtuoso before Punk. It would take years of learning an instrument before you could be in a soul group, or a disco group, or whatever. But punk and hip hop really opened that door for regular people who had something to say. And I believe that without the experiences of living in that moment and seeing your friends, or being in bands that just are like fuck it, let's play. Right? And coupled with also going to the Bronx and seeing MCs flow for the first time and like, all of that stuff. It's like, all of this was happening the first time it gave Basquiat permission to be like, well, I'm good at painting, I'm going to fucking do this. Fuck what everybody says, you know?

ED PATUTO: Yeah, I would totally agree. Hip hop was this new art form coming out of the Black community. But I felt like with hip hop, it was like, no folks, we’re going to do this on our terms, which we actually addressed in the final video with Todd Boyd, from USC about hip hop. It was a very intense moment after the seventies and the sixties, when this whole new wave of conservatism swept into the United States, Reagan—and Thatcher in England. There was a strong rebellion against that.

JAMES SPOONER: And what is the underground, if it's not reacting to something? And when you have oppressive things like Reagan, Thatcher, Trump, it makes the underground react. The underground, I'm including myself in this, we are nothing if we are not reactionary. But in turn, the mainstream is nothing if it's not pulling from the underground. So, we need each other, even though we often are fighting against each other.

Click here to see Part 2 Time Decorated: The Musical Influences of Jean-Michel Basquiat featuring James Spooner.