Text by Oliver Kupper

Portrait by Douglas Neill

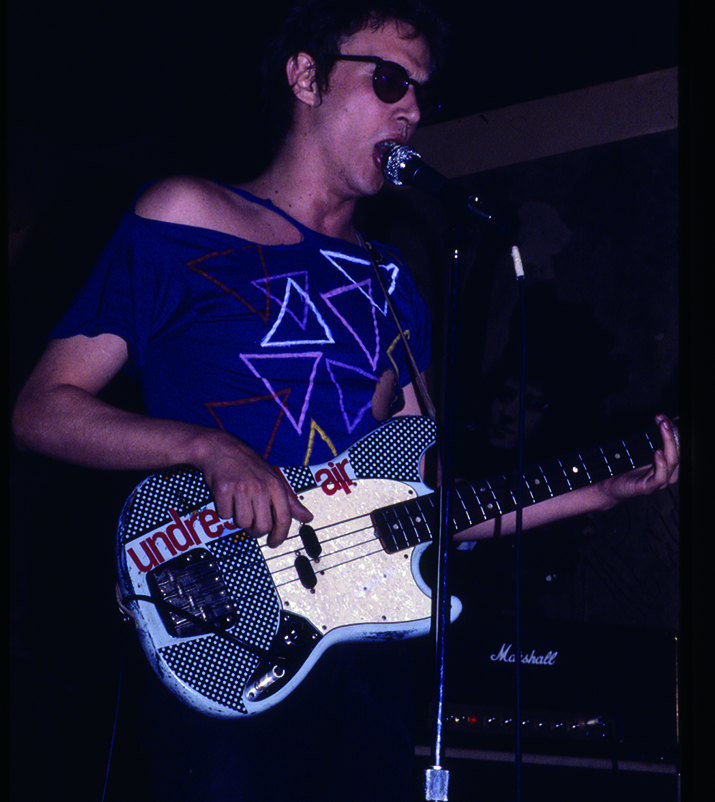

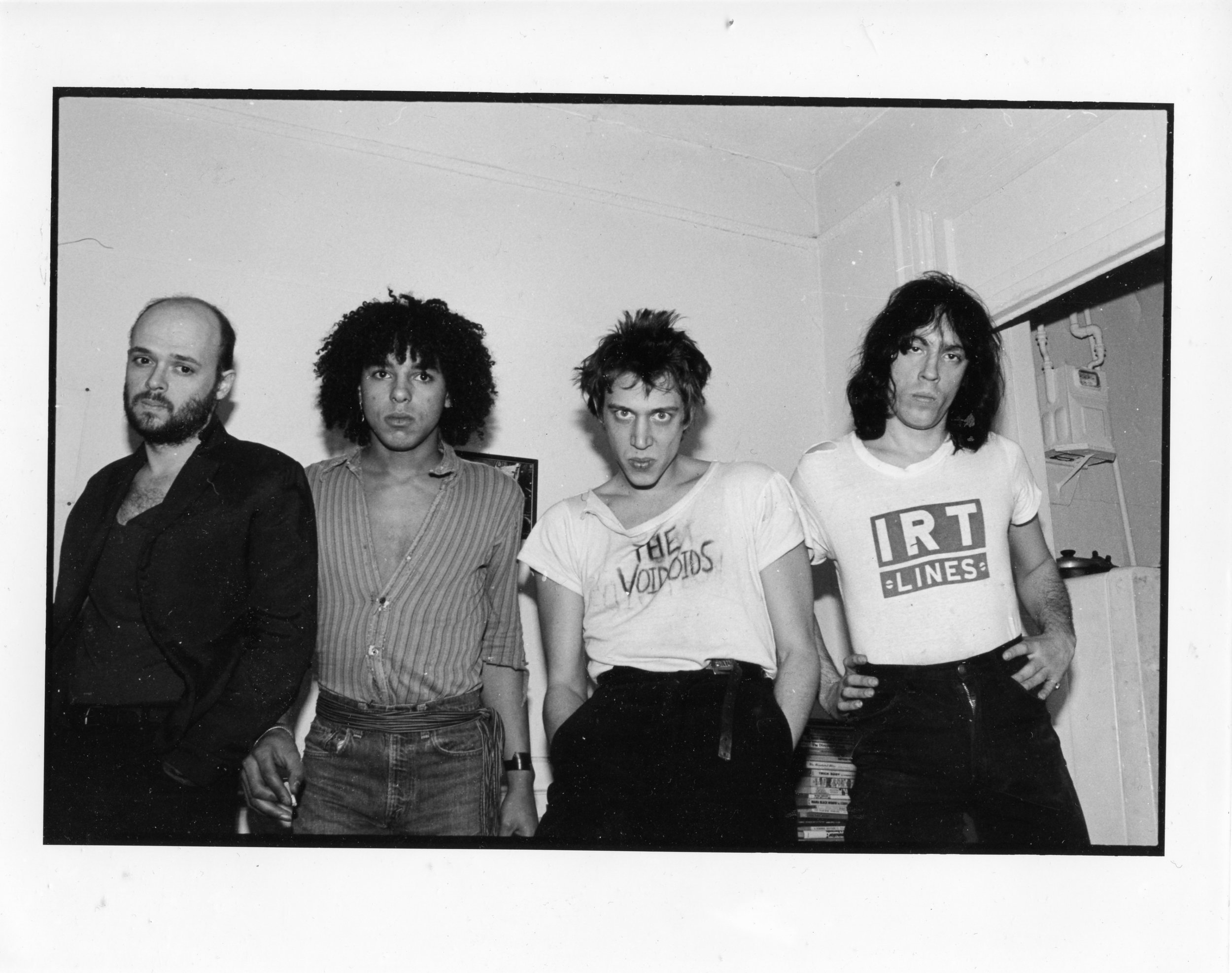

Archival Photographs by Roberta Bayley

RICHARD HELL is a pastiche, a collage of wedded epochs crashing down onto him, the rubble shredding his clothing and chipping his teeth. Many don't realize that Richard Hell was and is, and forever will be the first "punk." If it weren't for Hell, the Sex Pistols may have dressed and sounded drastically different. And Hell is the perfect nom de guerre because Richard Hell is a firestarter. His intellect is incendiary and sharpened by the ghosts of poets like Rimbaud and Lautremont alike, and philosophers like Spinoza and Plato. On a blazing hot summer day in Los Angeles, we met up with Hell at the Biltmore Hotel to discuss literature, music and his enduring legacy of beautiful revilement.

OLIVER KUPPER: We were talking about your relationship to LA [back in the lobby]. Maybe we should start there.

RICHARD HELL: I have this nagging interest in the battle of LA. I get to come here for a few days every couple of years. When I get back to New York, I have this urge to try to get a grip on LA. Then, when I return, on a trip like this, I am re-horrified.

What is it about LA that's horrifying? The people?

It's just this feeling that the whole thing is a dream world. All of a sudden, everything around you could just shatter into dust, devastation, and death. This is a pretty common perception about Los Angeles. It’s classic, but it's very powerful. On one hand, it’s this earthly paradise of hedonism and glamour. There are the avocado trees. You can take a dip and catch the rays. You can do your substance of choice and just lounge around in lush intervals. But, as we know, materially, this is all taking place on this thin surface. At any moment, there’s an earthquake that destroys everything. Water goes missing. Riots begin. The first day or two that I was here, I didn’t know the town that well. We would go out for a walk, trying to orient ourselves. Somehow, even though we felt we were taking different routes every day, they would also take us to the most horrifying, hopeless manifestations of squalor. The homeless people and the urine in the street, all the filth…

It’s intense.

When you turn right at the door, two blocks away is The Grove. All this ease and entitlement. For me, the place is scary that way. It feels like its own illusion.

One of the best portraits of Los Angeles is in Nathanael West’s “The Day of the Locust.” Have you read that book?

Yes. I think it’s the best book about Los Angeles. It’s really funny that Homer Simpson is in it. Yeah, that book is brilliant. He’s kind of my ideal for style. I don’t think he gets the respect he deserves. I take him over Faulkner. [Laughs.]

I want to go back a little bit. I want to talk about rebellion, because I think it’s an important part of what you’re about. Growing up in Kentucky, where do you think that rebellion came from?

I’ve been wondering. I don’t usually wonder, but I have been wondering lately. Mostly because of the [new] book.

That inspired the question.

Clearly, there is some impulse to be completely unacceptable. I don’t think of myself as being that way, but I keep finding myself in that position. I don’t know where it comes from. I would like to overcome it. It seems like a reflex rather than a conscious choice. I would rather have more control over it. For me, the reading last night was really significant. I do a lot of readings. I’m pretty comfortable with it, usually. I get nervous and uptight, but as a rule, when I hit the stage, the instincts take over, and it works. But last night, I hated everything about the presentation. Period. It made me realize that I have to put this book aside. On the subject of your question, I wanted to be as ugly as possible. And why would you want to be as ugly as possible unless you want to do what people don’t want you to do?

I thought your presentation was great, though. And the writing was great. I understood your perspective. Maybe there are people who don’t understand that kind of writing.

That’s the way I justify it to myself. I’m trying to write well, you know? Ultimately, I am kind of hopeless. I don’t have a lot of hope. The human condition doesn’t seem very good to me. [Laughs.]

Especially lately.

Yeah. But that’s an issue, too. These times are so dark. You don’t want to reinforce it. I don’t want the work to be affected because I don’t think it’s relevant to current events. But at a certain point, you can’t help it. Do I want to contribute to the despair? If this was for real, I should just kill myself. [Laughs.]

Be a martyr.

Yeah. That’s the way I would justify it to myself: the underlying horror of everything can be the substance of the content. That’s balanced with this intention to write as well as possible. That can be a counterweight. In a way, you’re still affirming something. But there’s quality in the “aesthetic” experience. Doing the book has been intense. It’s not easy to put yourself in that place, to deliberately indulge this feeling of meaninglessness.

In terms of your process, do you feel like an actor when you’re writing? Is there a voice in your head that is not you?

It’s always struck me that there’s a little bit of the writer in the writing. You have to present situations that you cook up. But it has to be conditional. I really love doing nonfiction.

It has to be easier.

It is easier in that you have the situations and the ideas to get to the bottom of it, to be as perceptive as possible. Then, when you’re doing fiction, that’s when the acting comes in. All you have is your own experience. You have to draw on that as vividly as you can in the moment of the writing. The actors talk about “being in the moment.”

Method writing.

Method writing, yeah. But I’m not very good at that. My memory is really bad. I’m really bad with dialogue. That’s a place where the acting thing is significant. Everybody is an actor, given a situation, and you have to make it real. I don’t have that skill. You see writers who can. When you read the dialogue in their books, everybody basically speaks the same way. While in real life, everyone has a distinctive voice. It’s rare for writers to be really good at that. My fiction doesn’t rely much on plot, or dialogue, or even structure.

When did you first discover the written word?

I think it precedes reading, in a way. In my autobiography, the title of it — I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp — came from a paper that I wrote when I was seventeen years old. When I discovered this paper — my mother had kept it in her files — I really identified with it. It was still me. That doesn’t always happen. I was doing a lot of research for my autobiography. That sounds odd, but I did. I gathered all of this evidence. I found a letter that I wrote shortly after I arrived in New York after having left home. I was probably seventeen when I wrote it. I literally did not recognize the person who wrote that. It wasn’t that I didn’t remember writing the letter. It was that I would have never guessed to have been the person who wrote it. It was a meaty letter, too. It had a lot of description of experience. I had no idea who it was. But this thing from when I was seventeen, that is different. I’m still that person and that person is a writer.

Film, too, is a big part of your interests.

I had a real education in film working at a shop in New York. It was called Cinemabilia. It was all film literature, but also paraphernalia—posters, stills, scripts even. That was the last day job I had. It was definitely the job I held the longest in that period of my youth. I sure liked movies, but everybody likes movies. It was there that I really got exposed.

That’s a great education to have. And did it keep you afloat in New York?

Well, that was at the end of my time there. I had twenty other jobs before. Usually, I was a meaningless clerk or delivery driver. I worked in a post office or drove a cab. At that time, in New York, it was so cheap to live. There were so many jobs and so many apartments. You wouldn’t have a problem quitting and getting another job. I probably lived in twenty apartments. I wanted to work as little as possible, so I had very little money. You could go three months without paying rent without getting evicted, so I did that over and over. There were so many apartments. I had a friend who recently had to get an apartment in New York and I was shocked by what she had to go through. They needed all her bank records. I had no idea it would come to that. When I was a kid, it was totally the tenants’ market.

I want to talk a little bit about The Sex Pistols because I think that’s an important part of the lineage of things, in punk especially. Did you know that they were ripping your style?

You know, I don’t want to rehash those things but it comes up so much. I write about it in my autobiography and I touch on it in the book of essays. It just seems kind of pointless to repeat stuff like that.

I’m just curious about your reaction to that, if there’s something other than shock or something other than anger.

It was funny. There was a certain level of resentment. Once I got to England and I saw how the punk bands were doing everything they could to conceal their debt to New York. I wasn’t about that because punk was supposed to be about honesty. But those bands were good and people don’t own ideas.

Cultures can cannibalize. It’s how culture spreads.

Sure, I stole plenty of stuff.

You talk a lot about heroin and sex in [your new book]. Do you think it’s hard to be a libertine in the 21st century? Do you feel like it’s hard now to be a punk?

You associate heroin with punk? You associate sex with punk?

No, but I could associate it with being a libertine.

There wasn’t very much sex in punk. That was something to me that was unusual in the history of rock and roll. There was this sort of rejection of sex. It was partly, I think, the desire to reject the hippies.

But that sort of ethos, that punk ethos, can that exist in an authentic form in this century?

I don’t know what “punk” means to you. I don’t know if we’re talking about the same thing. I don’t like using the word. I’m so accustomed to it for convenience now that I use it all the time because it’s necessary. But to me there’s not much overlap with people’s conception of what punk is. I mean that’s what that whole lesson last night was about.

I think a lot of people are confused by it and I think it’s been commercialized...

Well, just like any rock and roll. The general idea of it in the whole culture is extreme, youthful self-assertion of other qualities that adolescent kids have. Projecting in an adult world and trying to have fun despite it, and trying to be honest despite it. It’s just an explosion of that which is what rock and roll was about then. But you’re right. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of those values in music at present.

Yeah, what about music today?

It seems to have become completely accepted that the aim of music now - and it repels me - is to manipulate formulas in such a way as to plant a song in your head so that you can’t escape it. It’s inserted into your brain and you’re helpless because it’s this formula of how many beats a minute do this and where the hook has to come and what comprises it. It’s like creating a disease. It’s like manufacturing a virus that is impervious to any resistance and that will take over your brain. Rather than coming from any drive to communicate something or any kind of actual excitement, it’s just this manipulation of electronics in such a way as to enter and dominate you.

It is a virus. It’s a form of torture, I think.

I hardly listen to music at all anymore because I have just worn everything out. But maybe it’s also because I am old enough now. A lot of times a fuck ton of music, pop music, tries to affect your mood almost like a drug. You want to listen to a certain kind of music because you either want to overcome the way you’re feeling at that moment or you want to reinforce it. I don’t have much need for that anymore. Some music does date and we have just become so accustomed to it that it has no power anymore and I haven’t been able to find anything to replace it. There’s so little music there that really stays fresh.

What are some examples?

The exception that really comes to mind is James Brown.

I agree with that, one-hundred-percent. Soul music in general is so powerful.

Yeah, but I can’t quite listen to Al Green anymore. I used to listen to more Al Green. It just didn’t saturate me at all. But James Brown still works.

My remedy for that is to find a really great record store that sells soul 45s and then dig really deep and then find something that still makes you feel that feeling you had when you first listened to James Brown.

When I first discovered that Dave Godin’s Deep Soul Series, I think I lived on that for like five years. But even that, I am just too familiar with now.

What about Bo Diddley?

I can’t remember the last time I played Bo Diddley but I should try him again and see.

Do you scour the poetry section when you go to the bookstore?

No, I used to. When I was a kid I would always be looking for what was new and try to find somebody. But I’m kind of out of touch now. I don’t haunt the bookstores and look for something surprising and new. I know people I can rely on to recommend stuff and I find good new stuff that way. But I do enjoy a good poetry book when I find it.

The book that you are working on now, after last night, you are deciding to maybe rethink it?

I am trashing it. As I said, it’s been pulling teeth writing it. I’m finally accepting that there’s a reason for that. Maybe I’ll find a way to rework some portion of it into another structure. But I am not going to keep forcing it. I am bailing on it.

I thought it was gorgeous, like “the pendulum of goo” line. There’s some great lines.

Yeah, there are some passages that I really like. Maybe I’ll be able to salvage some of it.

I like that it’s a noir theme, but it’s set in this mysterious, post-modern environment.

I had ambitions for it and I feel like after this amount of time, wrestling with it, I have to acknowledge the impossibility.

Was your name “Richard Hell” inspired by Rimbaud’s “A Season in Hell”?

It had nothing to do with it. It occurred to me later but just because Tom [Verlaine] was taking blame. We decided to change our name because we decided our name was just too pedestrian and we wanted everything to have a message. I suggested he take the name of a 19th century French poet because he loves him. Mostly it was kind of a fantasy ideal of who they were. We didn’t know their work that well but we liked the vibe that we got about them - Baudelaire and Verlaine and Rimbaud. So I suggested why don’t you take one of their names and the first name that came into my mind was Gautier. That was partly because he was obscure, so it wouldn’t necessarily make any connection. But I realized it would be a little bit of an issue of pronunciation. So when that happened I thought oh fuck, hell, people are going to make these associations like Season In Hell. I chose stuff just because I like the ring of it, you know, I liked all the associations. I felt like it described my condition.

•