Fawn Rogers

Jestope, 2022

interview by Millen Brown-Ewens

hair by Justin Inman

makeup by Niohuru X

all images copyright Fawn Rogers

MILLEN BROWN-EWENS: Could you start by telling me a little bit about the paintings in your upcoming solo exhibition Burn, Gleam, Shine in Beijing with Galerie Marguo in July.

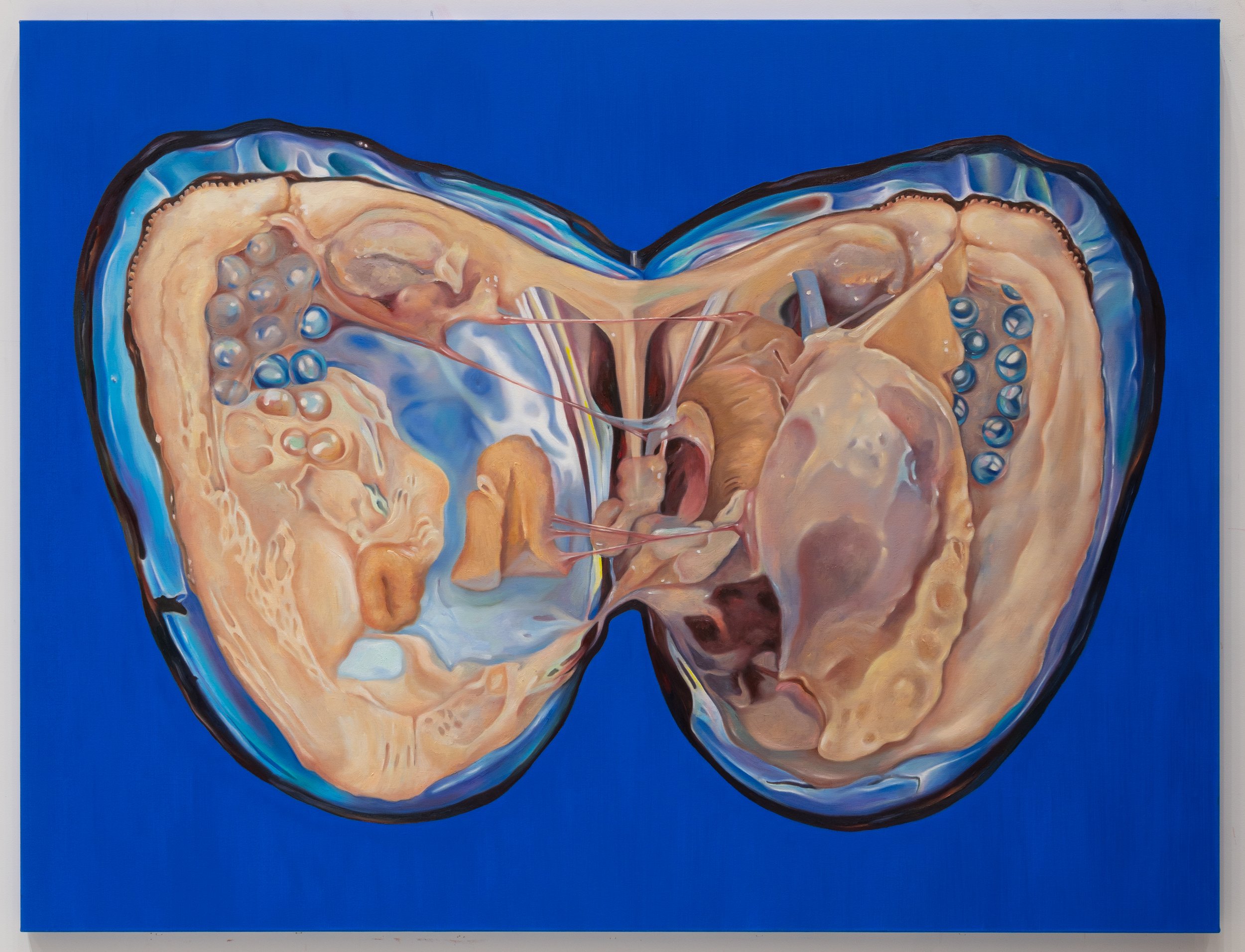

FAWN ROGERS: The work is from a series called The World is Your Oyster. The paintings are larger-than-life representations of sea personalities, which invite the viewer to dwell on the unbuilt world, death, and sex. Photorealistic from afar, at a closer view they are composed of painterly shapes and forms. They are seductive, erotic paintings that celebrate female sexuality. But I hope people will consider their wider resonances too. Human intervention in their cultivation has changed the primary process of their creation and relationships. Eroticism in this time is fraught with scary implications. We are so atomized as a species and removed from our origins that placing sexuality alongside environmental destruction almost feels forbidden, but I like things that feel forbidden.

BROWN-EWENS: What is the significance of the erotic and ostentatious image of the oyster in your paintings and how do you think this offers a critique of anthropocentrism?

ROGERS: I can’t help but to dismantle anthropocentrism in my work. At times it feels like a burden I was born with, it’s my reality, but essentially, I’m trying to find harmony through my work. The World is Your Oyster pays homage to these idiosyncratic and complex forms, inviting viewers to consider life, sex, and death simultaneously. While oysters are commonly considered luxurious rarities forged by nature, like many things, we have subverted the organic process of their creation. The oysters are harvested and pearls cultivated. An excision made to the oyster's flesh assaults the viewers' senses; ultimately this work is both violent and sensual, and at the center of these contradictions, the oyster is a symbol of lust, pleasure, opulence, and indulgence, all-consuming and offered up for consumption, a literal embodiment of the anthropocentric.

Oysters are both very fragile and highly sensual. It’s so easy to forget about the suffering of other lifeforms, they all want to live just as much as we do. The spider in the shower, let it live or kill it? I’m trying to place the human in patchworks of vibrant ecologies. I want to feel the delicacy and complexity of the tangled tension and vulnerable webs of life that surround us. This is connected to pleasure too. Our society represses sexuality, especially female sexuality, at the same time as it regards other life forms as unimportant. It is the same violent and disregarding gesture. It’s ostentatious to even be alive. Human existence is really a volatile party at the expense of all other life. Our role is both hilariously small and frighteningly disastrous. I try to call attention to expanding empathy for all life and not give up—dark humor helps.

BROWN-EWENS: Can you describe the conflicts between human nature and the natural world that arise in your practice?

ROGERS: It’s not just my practice, it’s my internal conflict because it’s how I view our world. I am trying to be present in a world that is being destroyed and full of suffering, and I am part of that destruction. When I paint a massive clam floating on a brightly colored, monochromatic background with its plump tongue sticking out, it’s darkly funny to me. It’s both sexy and gross to look at, and I have to kill it, consciously or unconsciously, to survive. We are supposed to have a conscience, and you’d think we would use it for creating a better world, but we don’t. Instead, let's go to Mars. It’s grimly ironic.

A good example from my practice is a work entitled R.I.P., a re-envisioning of the game of chess with chessmen depicted as sculptures of recently extinct animals. Black and white patina bronze on an oversized faux fur board, the animals are presented with regal dignity and personality. Each sculpture has material weight and nobility. Chess is a game of triumph, but triumph is a corollary of conquest. It is an enduring artifact of strategy, competition, domination, and has long been admired as a bastion of logic and order, but it is, at its core, a game of war, predicated on machinations of violence and obliteration. The game’s colonial history is traceable from ancient India, to the Muslim world, to imperial civilizations in Europe and northern Asia. Coupled with an emphasis on dominance, chess finds fresh implications in the contemporary subjugation of the natural world. Even the historical styles of chess—Romantic, Scientific, Hypermodern, and New Dynamism—allude to shifting cultural values and power structures, concluding, perhaps, with the game’s association with technology and artificial intelligence.

Chess has also long held a place of fascination for artists. Matisse, Man Ray, Duchamp, Paul Klee, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and Rachel Whiteread have all engaged with the game of chess. Jake and Dinos Chapman in their 2003, Chess Set, give resonant form to pre-adolescent male obsessions with fantasy forms of conflict, violence, and mutation. I wanted to repurpose a familiar form. In its prescient entanglements of order and chaos, civility and savagery, R.I.P. presses past a playful exploration of anthro-ecological history and evades purely dogmatic, observational, or elegiac orientations. The viewer becomes a player, autonomous yet complicit: a participant in the Anthropocene, at once a witness and contributor to a legacy of humanity, immortalization, and extinction.

Fawn Rogers

Free of God, 2021

oil on canvas

65 x 85 inches

BROWN-EWENS: What is ecofeminism and why is it important to distinguish?

ROGERS: I believe that the forces of patriarchy and everyone that support it oppress female-identifying and non-binary people, and they also exploit the natural world. At the same time, though, I feel that all people hold responsibility for our huge, sad state. For me, my work is liberatory. It makes me aware of the powers that emerge between people, and the world’s ecosystems. I am interested in a future evolution of humanity with empathy, less repression and destruction. In this geological era, our planet is a giant crime scene and we are all implicated. I am interested in finding ways to unleash emancipatory and sensual possibilities that may embed us more deeply in actuality.

BROWN-EWENS: Evocative titles add an additional layer to these pieces, calling on historical and pop cultural imagery such as Our Lady of Guadalupe for symbolic imagery. Could you talk a little bit about this piece in particular and its narrative within the series?

ROGERS: I find the concept of the Virgin Mary to be repressive. The idea of virginity as sacred and virtuous is a denial of the power of sexuality. I was interested in embracing Mary as utterly human. I wanted to free her from oppressive ideas that are antithetical to human equality. In this painting, you are looking at Mary’s giant sex. But it is not a desecration. I see it as a celebration of reality, a way of honoring life. I wanted to subvert the myths that have been written by men and supported by women, myths that have oppressed women across history. Poor Eve. Poor you, poor me! Ultimately, these ideas oppress everyone.

BROWN-EWENS: Your style incorporates hyperrealism with conceptualism to create these pillowy, silky scenes. Could you tell me a little bit about the interaction of these styles and practically how you set about depicting them?

ROGERS: I like the interplay between the representational qualities of painting and scale. My paintings of oysters teeter between realism and abstraction, depending on your point of view. They are my mandalas with a prayer, but I’m not religious. Before these paintings, however, I created a body of works called Eat You Eat Me, a two-channel video, The World is Your Oyster, then another series called Poisonous Harmony—all flirting with ideas that would come together in these current paintings. It was at this point when I found myself wanting to create these giant, sexy, wet, gooey oysters and through that deep dive arrived at wanting to have a visceral experience up close and personal with their forms. After painting them in a realistic way, I found the process a bit boring and decided to go back over each of them to take a closer look, and that’s how I ended up with this representational interplay that highlights the oyster’s many complicated and confounding qualities. They can harbor deadly bacteria while being a delicacy and perhaps an aphrodisiac. Plus, there are so many fertile concepts that attach to oysters. The expression “the world is your oyster” is said to young people embarking on life, but it comes from a Shakespeare play, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and there is an undertone of violence in how it is used. Dutch historical paintings of feasts often depict oysters and their symbolism for morality or sensuality. During the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1919, oyster beds were raided because they were thought to help prevent the disease. Oysters span everything from sexual pleasure to death, environmental violence and luxury consumption to femininity. They are even being used to build storm barriers in New York.

Fawn Rogers

Comet Tail #3, 2022

oil on canvas

14 x 11 inches

BROWN-EWENS: I’m intrigued by your photo series which you have described as exploring your Cherokee heritage. Do you think your ancestry has influenced your dedication and attentiveness to the natural world?

ROGERS: These photographic images were the start of my exploration into my Cherokee heritage. It is an oppressive history and is connected with a violent removal from the unbuilt world. My Cherokee ancestors walked the Trail of Tears to a reservation in Oklahoma. They became cotton pickers and also collected venomous water moccasin to survive. My great-grandmother was removed from her mother and placed in a home with European settlers. Her daughter, my grandmother, eventually made her way to the Oregon coast, where oysters were and still are harvested. To be free of the shame they lived with, because they hid their history, I chose to be naked in these images, and the photos contain symbolic details: horses, eagle feathers, pearls, handprints. If there is a single symbol for humanity it is the image of the human handprint. It can be seen on every continent and across all ages. The pearls are also fascinating. Everything from the history of the pearl with First Nations people to the way they are formed from irritants to gems.

BROWN-EWENS: What do you hope people take from this work?

ROGERS: I don’t expect any particular response. Maybe I hope people might react to this series in a way that is visceral. I want the paintings to draw you in and spit you back out. I do hope the collection will trigger thoughts about the fragility of life and the equality of all people. The splendor of sex. The beauty of the pussy!

BROWN-EWENS: I understand you’re set to have a busy year. What else have you got coming up?

ROGERS: June 24th, I’m excited to be included in the group show, Beach, at Nino Mier in New York. I just finished five group shows across Asia, the US, and Europe, including a Sotheby’s benefit auction curated by Nadya Tolokonnikova, who cofounded Pussy Riot. I also have an exhibition with Penske Projects curated by Sophia Penske at Phillips, which just closed in LA along with Boil, Toil & Trouble in Chicago curated by Zoe Lukov. In Beijing with Galerie Marguo, coming up July 13th is a solo exhibition titled Burn, Gleam, Shine. I have another solo in September titled GODOG in Los Angeles with sculpture, paintings and neon curated by Michael Slenske at Lauren Powell Projects. I’m also working on a new body of work, going from surf to turf and will be showing video, paintings, and sculpture with Galerie Marguo for a solo exhibition in Paris in October titled Come Ruin or Rapture. So we’ll see what happens after that!

Fawn Rogers

The Bee, 2023