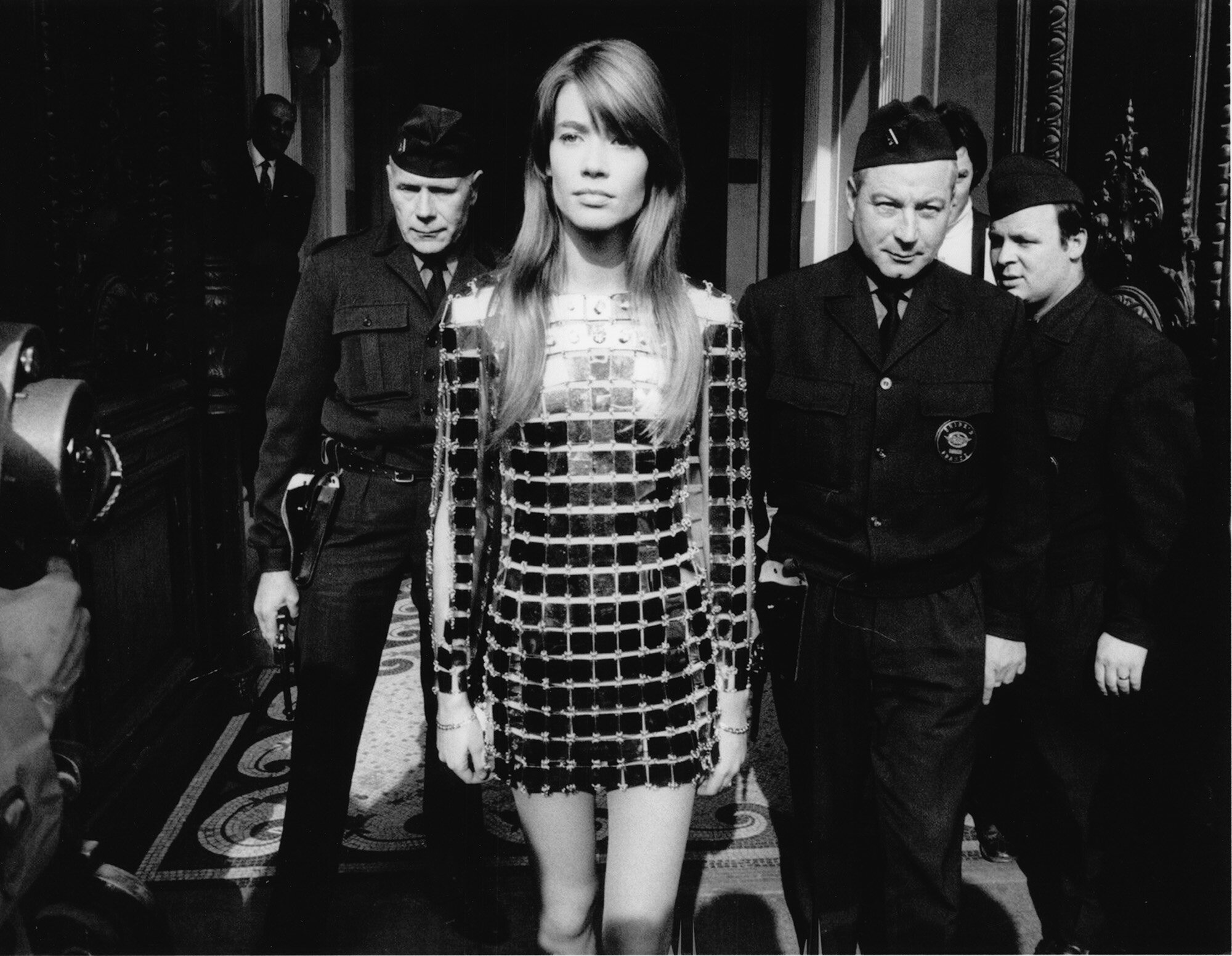

Venice, Italy, September 1966, © Steve Schapiro, courtesy of A. Galerie Paris

Françoise Hardy’s memoir

The Despair of Monkeys and Other Trifles

published in English for the first time by Feral House.

Since his break-up with Jane Birkin at the end of 1980, we had been seeing a lot more of Serge Gainsbourg. He was smitten with Thomas and telephoned me regularly as a distraction from his gloominess. I always more or less managed to lift his spirits although I don’t know how. After a bit of random chatting on one thing and another, I would hear his little short laugh, and the battle was won. Temporarily. His existential angst was an innate part of him and Jane’s departure had multiplied it tenfold.

My small crew was completely flustered and our graphologist overwhelmed the day he stepped into the RMC studio to take part in our show. He had gotten out on the wrong side of the bed that day, but our assistant Nelly, in awe at seeing him in the flesh, recklessly asked him how he was doing. He gave her a long dirty look and then mumbled “terrible.” The tone was set. His ostensible efforts to restrain an underlying aggressiveness throughout the interview made me ill at ease. He expressed himself so curtly and with so much dead air between words that the producer spent hours editing his remarks, bringing each word and phrase closer together to make them capable of being understood. When it came time for Anne-Marie Simond to read his remarkable graphological portrait, Serge vented at her. It was complete carnage. He refuted her statements one by one with his customary bad faith, and in his gem-like, reductive, and destabilizing way. Anne-Marie’s intellectual confidence was temporarily annihilated by the stress this caused and she did not sleep a wink that night.

Pleading exhaustion, Jacques had begged me not to bring Serge to the house. Despite my intention to return right after the broadcast, I felt obliged to accept his pressing invitation to get a drink at the bar of the Plaza, which was right in the neighborhood. His doctor, whose prescriptions he totally ignored, had forbidden him to drink and smoke, but he ordered two Singapore Slings right away. We had hardly settled in when he gazed at me in a most unfriendly way and blurted out: “Jane left me because of my polygamy, how do you deal with it?”

The sky came crashing down on my head again, even though I was clinging to an interview in which several years earlier Serge had said that it was the monogamy they had in common that brought Jacques and he together. I reminded him of it and acted as if I took his insinuation lightly. However, I felt devastated and he did not refrain from driving his point home: what was my secret? How did I manage to tolerate what Jane had never accepted? I only remember drowning in my emotions and not how I defended myself in order to save face. When the time came to bring him back to the Rue de Verneuil, Serge, apparently unaware of the havoc he had just wrought, began talking to me about a recently acquired firearm that Bambou,4 his new companion, had made him get rid of. She had saved his life, he swore, and his mood suddenly softened by this recollection because the temptation to use it was recurring and he would have succumbed to it sooner or later. Obviously, he felt he was in that kind of mood that evening. After mentioning his loneliness and his inability to stand it, he insisted that I stay with him. Moved by his distress, I brought him to Rue Hallé, where, on seeing us, Jacques muttered, “I knew it!” We chose to go out to the restaurant of the Hotel P.L.M. Saint Jacques, where we often went and which has since changed its name.

Once we were there, Serge got it into his head to create a cocktail requiring hard-to-find ingredients that took the sommelier a long time to bring him. When he finally had everything he wanted in the shaker and began shaking it, he dropped it, spilling its contents on the carpet. Thomas had to go to school the next day, and I was already renewing my attempts to speed things along when Serge finally deigned to cast an eye at the menu. But it was only to study the wine list, none of which, of course, he found suitable. After the unfortunate sommelier had managed to get permission to open the cellar, Serge headed there with a delighted Thomas while I was distressed at seeing the time we would actually dine receding further and further away. We left the P.L.M. around eleven o’clock and were packed in the car like sardines, when Serge, whose mood had visibly dropped, asked all at once if he could sleep at the house. Jacques dropped me off with Thomas before going to park the car, and I rushed to prepare a room. While I was moving into action, Jean Luisi, a family friend who had spent the evening with us, told me on the ground floor that Serge could not sleep without sleeping pills and they left to buy some at the drugstore.

During this period, it was impossible for me to go to sleep if Jacques was still out. He came home around five in the morning! This had given me time to ruminate over the revelations on his alleged polygamy and to get angry that he had not bothered to warn me not to wait up for him and Serge, even if it meant inventing some sort of pretext. His customary silence to my criticism exasperated me so much that I ripped the glasses from his face and threw them out the window. Incensed in turn, he swore that he would not be caught doing that again and he would stop seeing Serge. In fact, Serge had managed to drag Jean and Jacques all over the city, including a Corsican restaurant where his thoughtless provocations had aroused the murderous impulses of a customer who was a native of the Isle of Beauty. At their next stop, Castel’s, Serge threw an ashtray at someone’s head and almost started a brawl. We would later learn that he never slept that night and showed up at the scheduled time—nine o’clock in the morning—to film an advertisement. Like Jacques and Johnny, he was a real force of nature, and the saying that “a strong body is a calamity when it has the upper hand” applied to him as well—at least partially.

During the following week, Serge sheepishly invited us to dinner at Vivario, the Corsican restaurant where his lack of tact could have proven costly. His daughter Charlotte’s presence would oblige him to act reasonably, he assured me. Jacques stubbornly wanted no part of it and I don’t remember the miracle that allowed me to change his mind. When Serge showed up at the house, Jacques quickly told him that it was because of their nocturnal excursion that I had thrown his expensive glasses—worth five thousand francs—out the first floor window, which he had not been able to find. Like a true gentleman, Serge immediately wrote a check for this amount, which later became an exasperating subject of dispute. Jacques obstinately maintains that the check was written out to me—which was illogical in its own right—and that I cashed it, even though he knows full well that I am incapable of this kind of dishonesty or carelessness!

The dinner at Vivario ended as poorly as it started off well. Dead drunk, Serge and Jean climbed up on a chair and without caring in the least about the presence of the children, Thomas and Charlotte, performed a perfectly scandalous, obscene pantomime for us. But all of us—me heading the line—admired Serge’s artistic genius so much that we forgave him everything when he was sober again and had once again become a disarmingly courteous little boy.

Françoise Hardy in Paco Rabanne France, May 19, 1968

Among the noteworthy memories left behind by this enfant terrible were his dinner at Rue de Verneuil, to which the two Jacques, Coluche, and I were invited. While Serge was busy in the kitchen, we realized that he fully intended to serve us dinner on the low table around which we were sitting uncomfortably. This was hardly to the taste of my companions, all bon vivants for whom pleasure could not coexist with discomfort. In a matter of seconds they stripped a more suitable table of the art objects cluttered on top of it, knowing full well the sacrilege they were committing: the place of each object had been meticulously thought out by Serge, whose aesthetic sense was stamped by his absolute intransigence. When he came out of the kitchen and saw how greatly we had disturbed his order—in his eyes this amounted to finger painting over the canvas of a master or breaking a precious vase—he turned pale and had to make a visibly superhuman effort to not toss us out into the street. This was fortunate, by the way, as the evening turned out to be a great success.

Around this same time, I fell in love with “Ces petits riens” [Those Little Nothings], a marvelous song of great subtlety that Serge had written and composed in 1964. I wanted to cover it and Gabriel had the audacity to suggest another musical bridge of his own, with different harmonies. Serge balked at this but showed proof of a moving humility by accepting Gabriel’s changes—which truthfully, were welcome ones—when he heard them.

Serge’s superb book of photos of Bambou, which had recently been published, gave me the idea of asking him to take a photo of me for my record jacket. The session took place at Mac Mahon Studio on the Rue des Acacias, where Jean-Marie had toiled for the magazines Salut les copains and Mademoiselle Âge tendre, so I felt right at home. However, the impression that Serge’s assistant was doing nearly everything in his place worried me. My worries were justified, as the slides from this session were distressing. It is not easy for an amateur to master the finer aspects of flash photography. The lighting was poor, as were the photos. Luckily, after examining them carefully, I saw that there was one—only one—that would make a superb record jacket, and I felt an intense relief. How would I have ever told Serge, who was so sensitive to compliments, that nothing of what he and his assistant had done found favor in my eyes. His honor was safe, as was our relationship. No one who sees the elegant front cover of the album Quelqu’un qui s’en va would ever imagine that it was a miraculous accident!

At the end of August 1988, when I returned from Corsica, Serge Gainsbourg invited me to dinner. In the taxi that brought us to the Nikko Hotel, where he had reserved a table at the restaurant Les Célébrités, his incoherent and repetitive speech gave me the impression he had lost his mind. How many times had I heard him say he “would shoot” himself if he went senile! He had reached that point but obviously did not realize it. He first insisted on going to the bar and, once again violating his doctor’s orders, ordered two cocktails. When we went to our table, he ordered me a Petrus and a Cointreau for him. In dismay, I told him that quality wine was much less harmful than liquors and he would do better drinking this sublime grand cru from Bordeaux that to my great regret I would not be able to finish. This was a wasted effort. I remember it as an extremely heavy atmosphere. Serge never touched his plate and I did not know how to cheer him up. Moreover, he seemed to be blind and deaf to everything, a prisoner of the angst eating away at him.

Several months earlier, he had performed at the Zenith in front of a large and enthusiastic crowd. Serge enjoyed considerable popularity; he was the uncontested pope of French song, which he had revolutionized by making words sound like no one ever had before (among other things), and his hypersensitive, highly intelligent, talented, provocative, and break-all-the-rules personality was as fascinating as it was emotionally moving. But he was not a showman and his last performance was pathetic. Barely had his concert ended, when he sent someone to get me, and I found myself alone with him in a luxurious dressing room, which had been arranged down to the tiniest detail according to his instructions. He was obviously impatiently waiting for me to compliment him while I was having a devil of a time saying the opposite of what I thought. I only remember how profoundly awkward I felt, not how I escaped this impasse. All the love Serge received from his audience this evening did him a world of good, but when he was shown the video of the performance, he was so devastated by what he saw that I have often wondered if it might not have been better for him overall if his Zenith had never happened.

In the beginning of 1989, his doctors detected a small lump in his liver. They diagnosed it as an abscess and planned to remove it a month later. One evening when we were dining with our respective spouses in an Italian restaurant on Rue Le Sueur, Serge suddenly worried: what if he did have a cancer of the liver? “If that was the case,” I exclaimed, “they would not have waited so long to operate on you!” The logic of my observation reassured him and the evening proceeded as normal. But on Monday, April 10, Bambou called in a panic. She had just been told that Serge really did have liver cancer. The doctors had not spoken of it to anyone to avoid any leaks that might give him ideas. Moreover, they had not operated on him earlier because of the extremely poor condition of his heart, which was at risk of giving out under anesthesia.

His heart did not quit, and the length of time needed to revive him and for him to leave the hospital was quicker than anticipated. I saw Serge at the Raphael Hotel bar, where he enjoyed hanging out. The elimination of alcohol had restored his spirits and the pounds he had dropped made it seem like he was floating in the odd, too-short blue jeans he was wearing. I can still see in my memory his silhouette moving from the back: he had the air of a little sixtyyear- old boy whose fragility leapt out and touched my heart. He survived two years following his operation never dreaming he had cancer. I was constantly expecting to hear the news of his death during this time. When I thought about him, when I found myself in his neighborhood, a great sorrow flooded me that every day brought us closer to the day when he would no longer be there.

There was a memorable evening with Étienne Daho and Bambou. In the middle of the meal she became extremely anxious because Serge did not answer the phone though he was coming down with the flu. We interrupted our feast to go immediately to the Rue de Verneuil. Serge had not yet returned, and we waited for him in the entrance of the Galant Verre, the restaurant facing his building. When he finally returned and opened the door to let us in, I was shaken by his appearance: his complexion was waxy, he was perspiring, and he had the air of a zombie. We took a seat in his living room/museum and were unable to prevent him from emptying a half-bottle of port, although he was taking antibiotics. All at once, he brought his hand to his chest and started groaning: “My heart, my heart ...” while a clear fluid began spilling from his mouth. It was like a nightmare. Bambou ran to get a napkin, while Étienne and I stoically prepared ourselves to witness the final moments of our illustrious friend. He refused to go to the hospital, and it was only when we had Bambou’s assurance she would remain with him for the rest of the night that Étienne and I, quite shaken, took our leave. We thought we would learn that he had died in the night, but when I talked to Bambou on the phone the next morning, she told me that Serge had woken up singing (Cloclo) Claude François’ hit “Alexandrie, Alexandra” at the top of his lungs.

On Saturday, March 2, 1991, several friends came to have dinner at Rue Hallé. One of them, Gilbert Foucaut, a music programmer for television, called me around two in the morning quite devastated. He had just heard on the radio in the taxi taking him home that Serge was dead. No matter how much we were expecting this news, hearing it caused an unimaginable shock. Several days earlier, Thomas had gone to Vézeley, and Serge had enthusiastically told him about the new album he was putting together. Rumor spread that he had died in his sleep and only the certainty that his health problems would have assumed intolerable proportions if he had lived longer softened our pain. It is a terrible thing to say, but at the point he had reached, dying this way—quickly and apparently gently—was the best thing that could have happened to him. There were assuredly quite a few of us who felt his departure signaled the end not only of an entire era but also our youth.