interview by Jeffrey Deitch

photography by Flo Kohl

Hajime Sorayama’s trademark chrome-plated erotic pin-ups are erotically charged symbols of a cold, dystopian future, but there is much more to these gynoids than meets the eye. Blending a rich history of Japanese illustration, Tokyo underground, and Western pop, Sorayama’s sexualized machines are metaphorically prescient of the blurred lines between sex and labor, the corporeal body and artificial intelligence, the past and future.

JEFFREY DEITCH About six years ago, I entered the Nanzuka booth at Art Basel Hong Kong. Usually there’s a lot of sameness at art fairs, but this was a complete and coherent aesthetic world. I was just amazed. I said to Shinji [Nanzuka], “I want to work with you. I want to collaborate. I want to do things with you.” And Shinji curated a great show for us, Tokyo Pop Underground. Hajime Sorayama was, of course, the star of the show. It brought to New York and Los Angeles this whole aesthetic that Shinji has articulated and translated. Shinji, maybe you can talk about Tokyo Pop Underground and this unique approach that fuses fine art and pop culture, Japanese culture, and international art.

SHINJI NANZUKA In Japanese history, we didn't have the word or context for fine art until relatively recently. Of course, we had applied arts, like printing and ceramics—objects we used for daily life. But only during the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when Japan started to become more receptive to the Western world, did we translate the word art into the Japanese language, which became bijutsu—bi for beauty and jutsu for craft. Then, after the complete devastation of WWII, we imported a new, democratic philosophy from the United States. But most Japanese artists didn’t understand contemporary art. We had a deeper cultural context within comic art, like manga or anime, or magazine illustration. And even before the war, we had a Parisian art style from the 18th or 19th century, but it was very hierarchical. So, there wasn’t an understanding to explore this new cultural aesthetic in the art field. Personally, I had a much deeper understanding of some of the artistic subcultures. And that’s why I wanted to work with artists within the commercial field, like Sorayama, Keiichi Tanaami, Harumi Yamaguchi, and more. These artists are more important to me because they represent a new aesthetic language in Japan from the ’60s and the ’70s. And they had an attitude to represent our struggle after the war, which implemented Western artistic philosophies into an Asian country. This is what I wanted to explore in the Tokyo Pop Underground show together with Jeffrey, which was a big project for me, a dream project. I’m very happy that you made it happen.

DEITCH Mr. Sorayama is such a cultural hero. How did you connect with him and bring him into the mainstream art world?

NANZUKA Sorayama never thinks of himself as a mainstream artist. (laughs) He says that he is more of an entertainer. You know that he is quite popular in Japan. Everybody knows his design, the Sony AIBO, or perhaps his album jacket art, like for Aerosmith’s album, Just Push Play (2001). In the ’70s and ’80s, most Japanese people must [have] run into his work because it was everywhere in the city: on advertisements and magazine covers. When I had a Keiichi Tanaami show for the first time in 2007, Sorayama came to the opening and I asked Tanaami to introduce me to him because I really wanted to work with Sorayama. Erotic art is not rare in Japan. It’s kind of popular, even for young people. Even in newspapers, it’s really easy to find his work. So, I never thought he would be too controversial for the art world, because we can talk about sex in the art world here. That’s why I didn’t hesitate to work with him, even though nobody was interested in him. In the beginning, though, I struggled because I wanted him to paint new female robots. After all, he wasn’t doing that anymore when I met him.

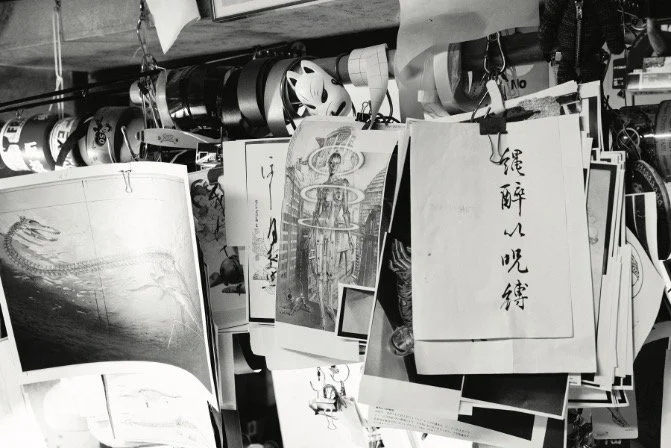

DEITCH So, I see there are works in progress in the studio. Can we talk about the new paintings?

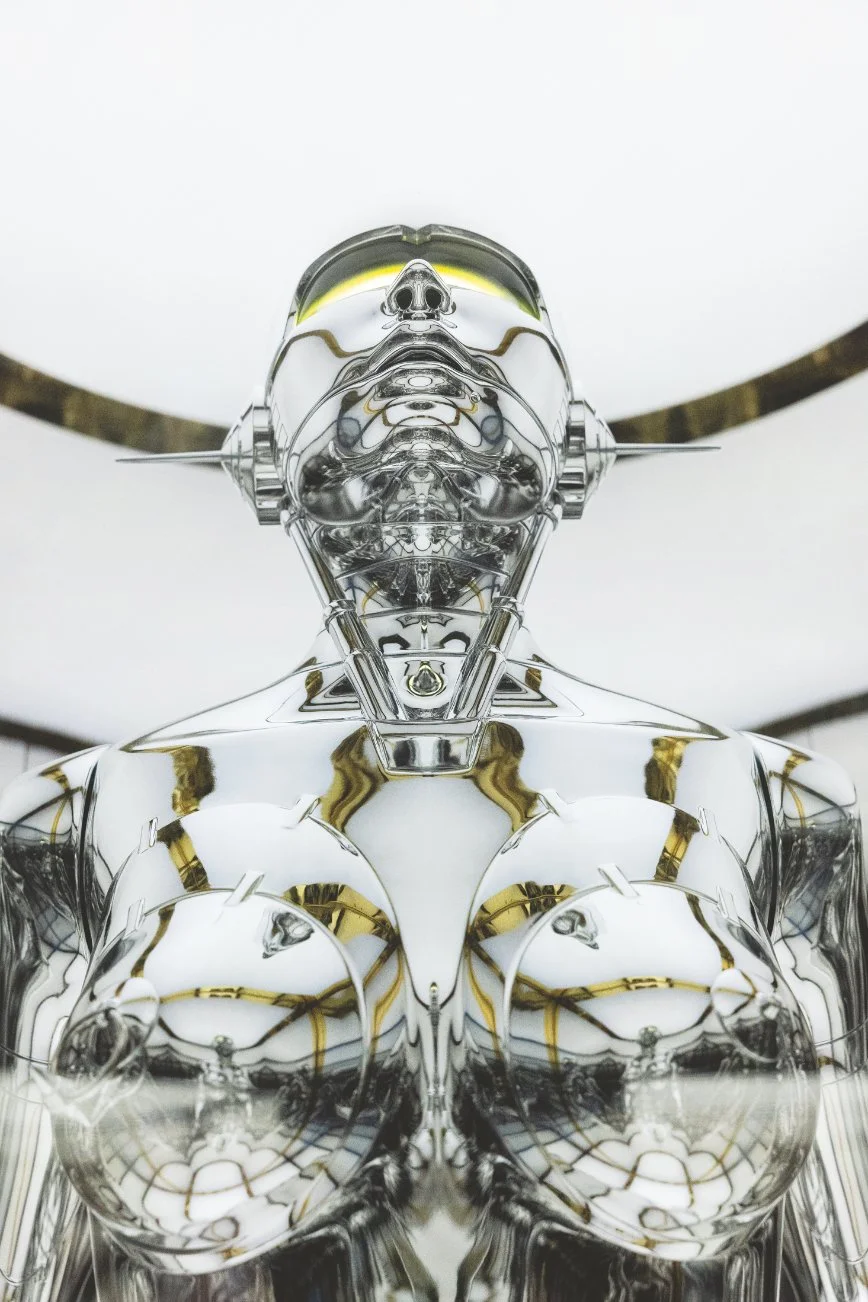

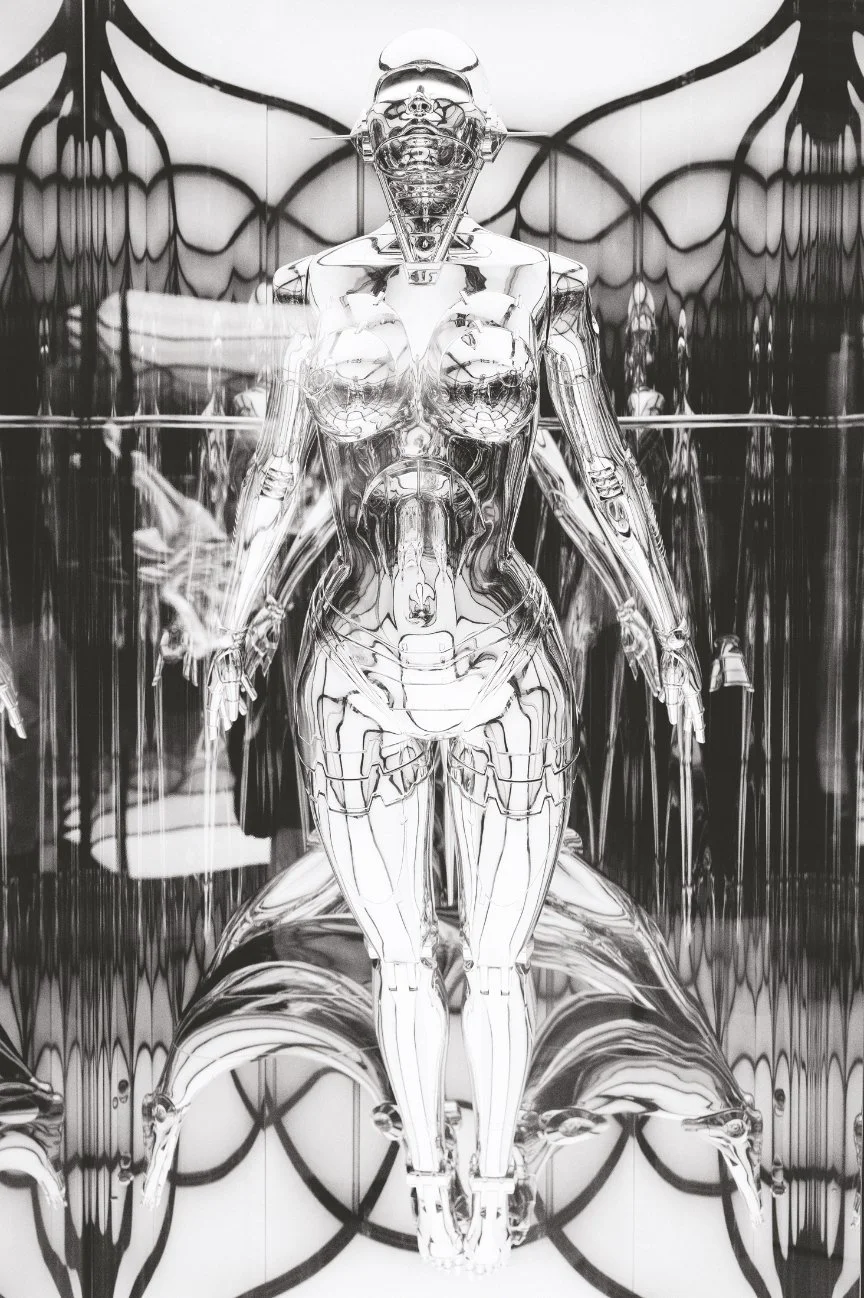

SORAYAMA I painted my version of Maria from the movie Metropolis (1927) by Fritz Lang for an exhibition at the Pola Museum in Japan. Maria’s original design is not as feminine, so I tried to use my form of plastic surgery to make her look more beautiful and feminine, more proportional, make the legs and the arms bigger, the body more shapely. I tried to paint a human skin but it turned out to be metal (laughs). In Metropolis, as Maria transforms into a robot, there is an electric signal surrounding her, so I painted the circular currents.

DEITCH It’s so fascinating that this is very much a combination of Japanese and European-American aesthetics. And It’s also a lot of the fine art tradition: the history of sculpture, but also the history of popular culture. Sorayama mixes it all.

SORAYAMA This is the challenge for me: to create a better aesthetic for robotic design in the 21st century. For example, the original Maria was too classical, too lavish for me. I wanted to make an update for this century—an old identity breaking through to the new.

DEITCH It’s very interesting—the eroticism of the robot. This is something that characterizes contemporary society, that there’s an erotic desire that is connected with a robot. That a robot can create this desire in a more intense way than a human.

SORAYAMA (laughs) You think so?

DEITCH Well, that’s the big question. I saw the reaction to your sculptures in our show. People were so erotically attracted to them. The question is: are people today programmed to be more erotically attracted to a robot, an image of a robot, more than an actual human in some cases?

SORAYAMA This is what I want: to bring people’s wishes and desires into my paintings. I always paint over and over my previous work, and so far this is my latest and best version. I make it like a practice, an exercise. Most likely if I saw this painting again in three years, I would want to change everything about it.

DEITCH It looks like such a powerful painting.

NANZUKA I always meet with young audiences going to see Sorayama’s work and they think it’s only about the erotic painting. Even artsy people have said Sorayama’s work is just about sex. He always tries to surprise people.

SORAYAMA I’m always looking for anything new to make people surprised.

DEITCH There’s a comment that you made when I asked about introducing Sorayama into the mainstream art world, Shinji. You said, “Well, he doesn’t want to be in the mainstream art world—he’s more interested in just being part of contemporary culture rather than specifically the art world.”

SORAYAMA I don’t really care about any category of art or subculture—I'm just happy if it’s interesting.

DEITCH I want to ask you about something special that we arranged. Elon Musk, who’s not known as an art collector, was fascinated by your work. He bought one of your sculptures, installed it in his home, and then asked, “Can I talk with Mr. Sorayama?” What did you talk about with Elon Musk? Did he want you to come to outer space with him?

SORAYAMA I actually had two meetings with Elon Musk. He asked me to make a flag for his Mars colony—like the flag of a country. I suggested one of my erotic robots flying over Mars. Elon was not satisfied because he had something specific in mind, like a spaceship landing in a civilized Mars colony. I said, “If you want a normal illustration like this, you should go to another artist.” He listened to my opinion and we went our separate ways. We just talked. It’s a very funny story.

OLIVER KUPPER Do you see your robots as being some harbinger of what to imagine in the future?

SORAYAMA (Laughs) I’m not interested in the past or future. But people do recognize my work as futuristic. I just like metal as a material. It’s shiny and I like the way light reflects from it. And I like the female form. So, I just combined what I liked and that's it. But if you think about the future of robotics, people probably won’t use metal because it's heavy, and it's very hard. Carbon is maybe more realistic. The fact that people think my paintings are futuristic is a trick of the imagination.

KUPPER So, it's more of an erotic fantasy.

SORAYAMA Yes, these are my desires. It’s my take on desire. Eros is not only sex. But, what’s funny is that sometimes I’ll post these realistic paintings of female nudes on Instagram—usually their AI bans this type of art but because my nudes are robotic, they are never banned. So, my robots are fighting against their robots (laughs).

KUPPER Jeffrey and Shinji, I'm curious about both of your instincts to show work like Hajime's—work that fits somewhere in the netherworld between commercial and fine art. To have the bravery to show this kind of work.

DEITCH When you show work that has a transgressive quality, it's essential to show it in a perfect presentation. So, we worked quite hard, and Shinji's installation plan was brilliant. We presented the work with such authority. Everything in the installation was perfect. People saw the same kind of standards that you use for artists who were well-established in the fine art space, and the work became very convincing. So, yes, if you're going to show work that challenges people, you've got to do it with total confidence. Don't hide it behind a black curtain. Present it the same way you would any other artist who you think is outstanding and who you admire. And we had many museum people, in addition to lots of young people, who could relate to this work as an extension of a subculture that they participate in.

KUPPER Shinji, where did your instinct to show work like this come from? I mean, there are so many artists in the world. What was it about these artists that made it interesting in a fine art context?

NANZUKA People still think of fine art in the traditional sense or “arts for art’s sake.” But there are creative people everywhere and in many different fields and contexts. Like I said earlier, we have a deeper context for manga in Japan—more than fine art, probably. For me, working with these established commercial artists in the fine art field, I have to explain their context. Context is kind of like a trick I use as part of the explanation. This is why it’s good to know art history, because I can use an art language. So, that's why Nanzuka is in a unique position—between a commercial and fine art gallery. It's totally natural for me to work with those commercial artists because commercial artists have experience working with clients. They have very flexible minds, like Taanami, who's now eighty-six years old, and Sorayama is seventy-six years old. These two can talk about creativity together and what they can do next—this creativity and flexibility is important in the contemporary art field.

DEITCH Something that I want to mention—with my experience of presenting the two Tokyo Pop Underground shows, the audience does not differentiate between fine art, illustration art, commercial art, or subcultural art. Maybe the museum elite differentiates, but that wall is breaking down. The young audience does not. So, there's a lot of similarities now between the Japanese audience and the American audience of not looking down, saying, “Oh, this isn't real art.” It was really fascinating to see the whole art world opening up and changing.

KUPPER Hajime, how do instinct and intuition play into your work? Where does that instinct come from? How do you use instinct? And what is the mechanism of instinct in your illustrations, sculptures, and paintings?

SORAYAMA I have a memory from being a child—on the way back from school, I stumbled upon a small metal factory. There was a big metal cutting machine and I watched a shiny spark produce a piece of carved metal. From that moment, I was addicted to going to this factory and watching these machines every day. I still like watching metal: my eyes follow all the metallic parts in the city. Of course, I recognize a metal fetish in myself. There is always shiny stuff in the studio. But, I’m not really too conscious about my inspirations. I just know that I have never stopped. I just want to constantly paint in my studio. I don’t care about high art, commercial art, low brow, high brow, I just concentrate on my creative desire. That’s why I was very comfortable during COVID (laughs), because it was quite silent in the studio.

KUPPER We are living through a new culture war where erotic art is being censored and even banned. I'm glad you are continuing to push the boundaries. Is it similar in Japan right now?

NANZUKA It’s much better in Japan than in the United States. I'm not afraid to show work at my gallery. People never try to shut down my shows.

SORAYAMA Instead of facing that backlash head-on, there’s a way to get through it and make fun of the pressure; to use my creativity to get through it. I’m happy in my little category and I don’t listen to those high-minded people.