interview by Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi

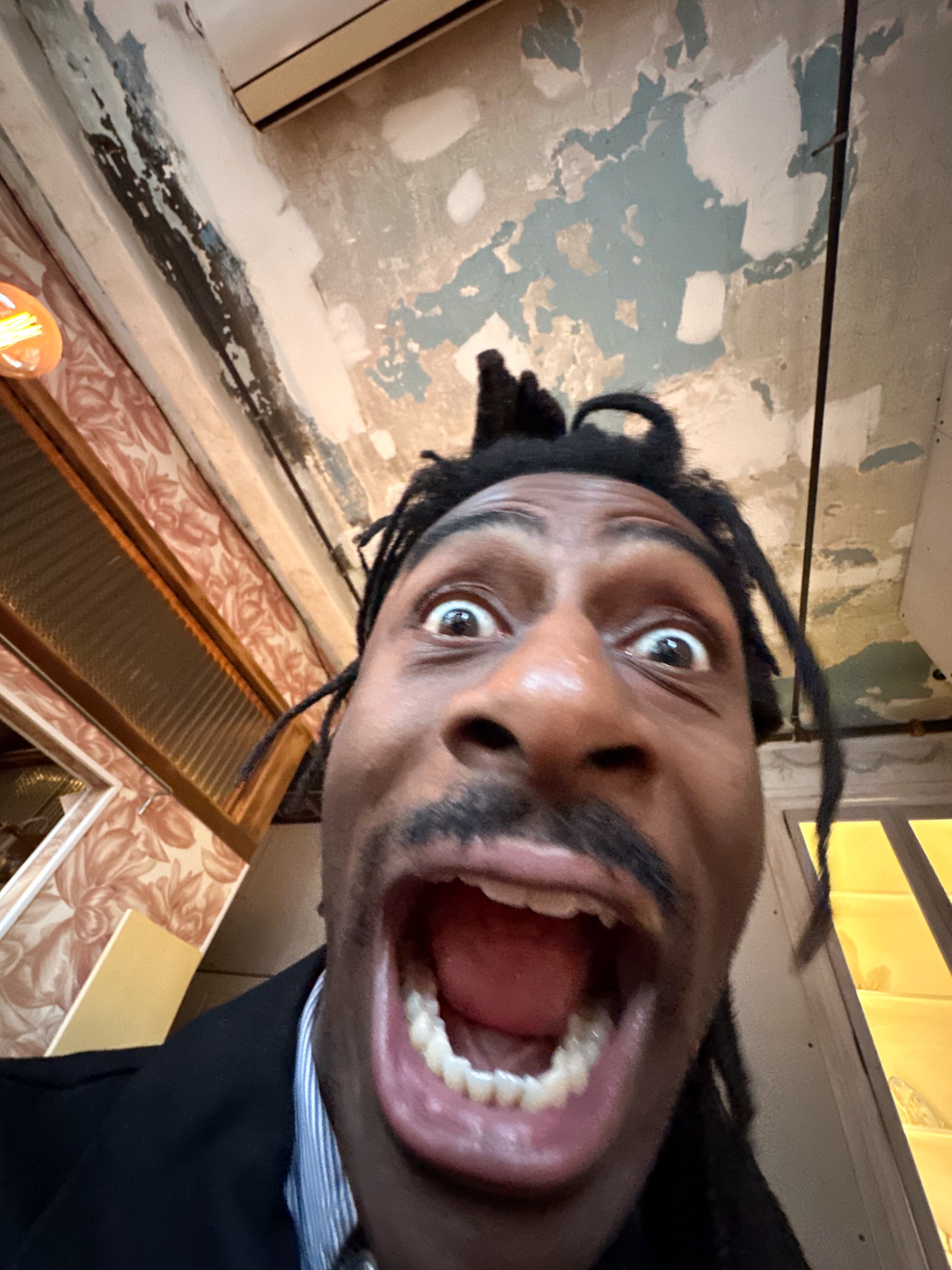

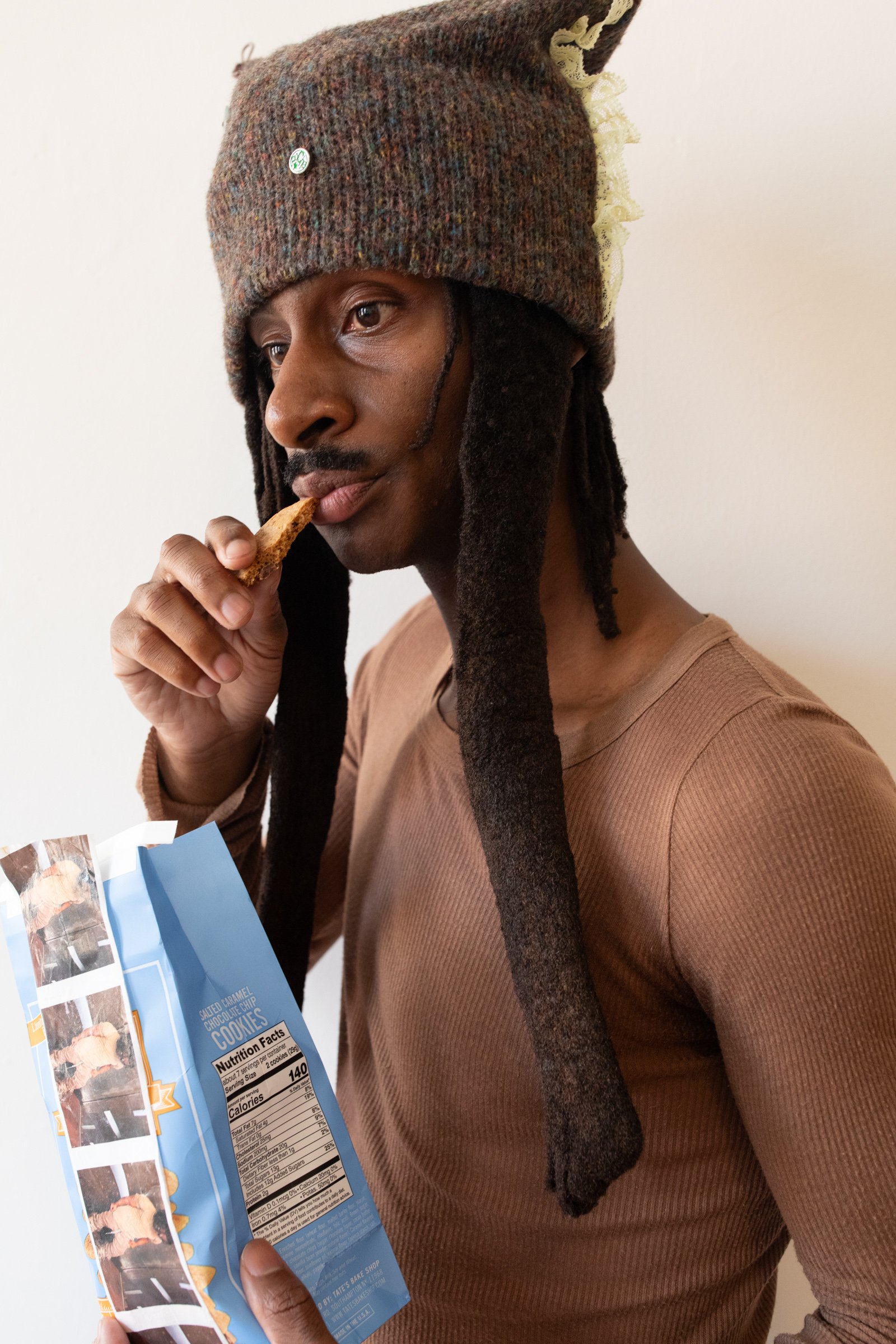

photographs by Jan Gatewood

IKECHÚKWÚ ONYEWUENYI Can we talk about how the figures entered your work?

JAN GATEWOOD My drawing practice aims to produce dynamic images that seamlessly employ abstraction, figuration, and text. My initial impulse to depict animals was primarily due to political and formal concerns I have within art making. I believed early on that abstraction alone wouldn't be enough for my practice. Additionally, I'm interested in the conversation of representation. I felt that if I depicted animal bodies in my work, it would allow many demographics to attach themselves to my practice and simultaneously create a viable way for me to explore my interest in materials.

ONYEWUENYI When you say abstraction is not enough, can you talk a little bit more about that?

GATEWOOD I like to think that using abstraction, figuration, and text speaks to the complexities of the concepts embedded in my work and exposes more access points for the viewers. More simply put, I like to see if I can give something to everybody. Part of the fun of art making for me is the idea of the impossible. I like the difficulty of trying to make a balanced and exciting image using methods that may be at odds with one another. The difficulty of that task produces the possibility of making a visual language that's synonymous with—but not exclusive to—me.

ONYEWUENYI You mentioned being very systematic—how does that inform that first abstract impulse? Some abstract artists are very precise in how they apply the materials. Is there a rule for approaching this initial experimentation?

GATEWOOD My drawings are materialized through resistance and a slightly chaotic system. That resistance is created through chemical reactions happening in and on top of paper. My abstractions are done with a range of materials including fabric dye, salt, bleach, glue, food, debris, etcetera. The figures present in my drawings are rendered using graphite, oil pastels, and oil sticks. Because the oil and water-based materials can't mix, I've created a system that allows me to do two things at once. So, in terms of my production process, there aren't too many strict rules but there are definitely consistent guidelines that I allow myself to explore.

ONYEWUENYI It almost seems like, compositionally, you are using the background to dictate what comes after.

GATEWOOD The initial mark-making informs the placement of the figure and subsequently the moves made towards the completion of the piece.

ONYEWUENYI The animals have a very ludic, playful quality about them, which makes me think of nursery rhymes. Talk to me a bit about some of these figures and what they mean to you.

GATEWOOD Depicting animals is a solution for dealing with representational imagery in various ways. I'm weary of identity politics immediately dominating my work. Obviously my race, class, gender, etcetera, heavily inform my work, but I wanted to also make room for discussion about my ideas and how they're realized. I think a lot about humor, tone, and the importance of playfulness; working with storybook or childlike images helps me communicate that.

ONYEWUENYI I'm thinking of the instinct theme, and the role animals play in psychoanalysis. Looking at the case studies of Freud where maybe a kid is scared of a horse, but he's not really scared of the horse, it's tied to his sexuality or angst with his mom. Thinking about the images that we use or the symbols that we use, where do they lie in our subconscious? Can we even locate them? In relation to childhood nursery books—those images stay with us and never seem to leave. How does that connect with your work?

GATEWOOD The possibilities of the viewers' psyche fascinates me, but my use of animals is more of a practical concern than an interest in, or knowledge of psychoanalysis. In addition to the reasons I touched on earlier, my use of animal imagery allows me to explore repetition and how it affects the understanding of an art practice as things progress.

ONYEWUENYI It also makes me think of George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) and his use of animals to comment about society. But I think with a lot of these animals, you come to it with your own perception and then when you see the work, you reinterpret that perception. It's kind of like this interesting hermeneutic.

GATEWOOD Oh sick, I'm not familiar with that book. I'll have to check it out. With that being said, the viewer’s perception and their subjectivity is something I value and don't want to take for granted.

ONYEWUENYI Some of the animal subjects of your work are cute and some of them look quite menacing. There’s a book about cute aesthetics by Sianne Ngai, called Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (2012). She's making the claim that minor affects have such a big role in how we think about the world—the way we talk about things. I used to work at a buy, sell, trade store and these young high school girls would come in and they would say, “What do you think of this dress?” And one girl's like, “It's cute, but it's not cute. It's kind of cute.” With the repetition of the word, it's almost not landing on anything, but it's landed on something. And I think those minor affects are really how popular culture understands aesthetics. I mean, talking about aesthetics, it's very lofty—Heidegger and all these people talk about that shit. But for the common man, cute is a very important word. So, there’s something about the animals that reminds me of this idea of cute, but how it helps make sense of society, culture, what we think is desirable, or not, and whether or not we want to attach ourselves to something.

GATEWOOD That's a fun observation and example. Typically, I try to skillfully use attributes of cuteness and its relationship to desirability to balance a work and articulate the presence of multiplicity. Cuteness is a thin line for me, so I believe it's best to complicate it. For example, I might pair an image of a lamb with some gestures that could be read as "violent.” Of course, the idea wouldn't be to push any direct narrative, but to reiterate the importance of the viewer’s subjectivity.

ONYEWUENYI Another book is Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism & Schizophrenia (1980). The book talks about schizophrenia within culture, but one of the ideas is the idea of becoming. One of the points they drive home is “becoming-animal.” And that gets you towards this place of seeing we are all in this space, navigating the world, by committing to becoming or becoming human, becoming a woman, becoming an animal, you are opening yourself up to experiences that are different to yourself. It feels like there's some of that going on in your work.

GATEWOOD Absolutely, I'm so glad you mentioned that. My 2022 show at Smart Objects titled Tiptoe Hassle was heavily informed by Deleuze and Guattari's concept of machines. Machines being a political concept designed to prioritize new ideas was really useful for me in terms of figuring out ways to comfortably push the ways I think about my own artistic production. I see that being connected to the “becoming” in several ways. One of which being the way that artworks actualize through their connections to the world. This inevitably involves a constant state of change and becoming. Embracing these changes leads to a greater self awareness, which is a material I'm focused on harnessing more in my work.

ONYEWUENYI You know, one of my classmates back in New York, he's doing a PhD in architecture at Princeton. He sent me this essay by Guattari where he talks about how we all have impulses, but what does it mean to celebrate them and actually let them be? What does it mean to create a society that allows space for different impulses? And Guattari was part of this group of French psychoanalysts who created this community for folks with different mental abilities and disabilities. Everyone in the hospital, from doctors to patients to staff, wore the same thing. And the patients have free reign to move around the premises. It was a way to welcome impulse through movement and activity, and not create these hierarchies. I have a brother-in-law who has schizophrenia, and he has these delusions and visions that are so real to him. But within our capitalist society, his visions are very anti-capitalist because they don’t operate towards this sense of labor and production. But what if we made space for his world? What would that look like?

GATEWOOD There's a lot of beauty in that concept, it's cool to hear that empathetic action came from their thoughts. I'm curious to know more about how that affected patients. I find so much beauty in the idealism that art, language, and philosophy can occasionally actualize. Maybe that optimism is one of the reasons why so many of us dedicate ourselves to the aforementioned.

ONYEWUENYI You mentioned that you don't personally want to be read in the work, but how is the work a kind of self-fashioning?

GATEWOOD In my drawings, for the most part, I actively remove anything that alludes to my physical appearance, in part because of issues I had to resolve internally around creating images of black people that will be bought and sold. I wanted to disperse my image on my terms and use it to heighten my practice. My past two solo exhibitions have had hundreds of free artworks all using a selfie I took. The intention was to make sure my image is linked to a specific part of my practice, make commentary on exhibition length, and gesture toward generosity. Perhaps it's about autonomy, perhaps it's about control. I'm still finding the language.