interview by Oliver Kupper

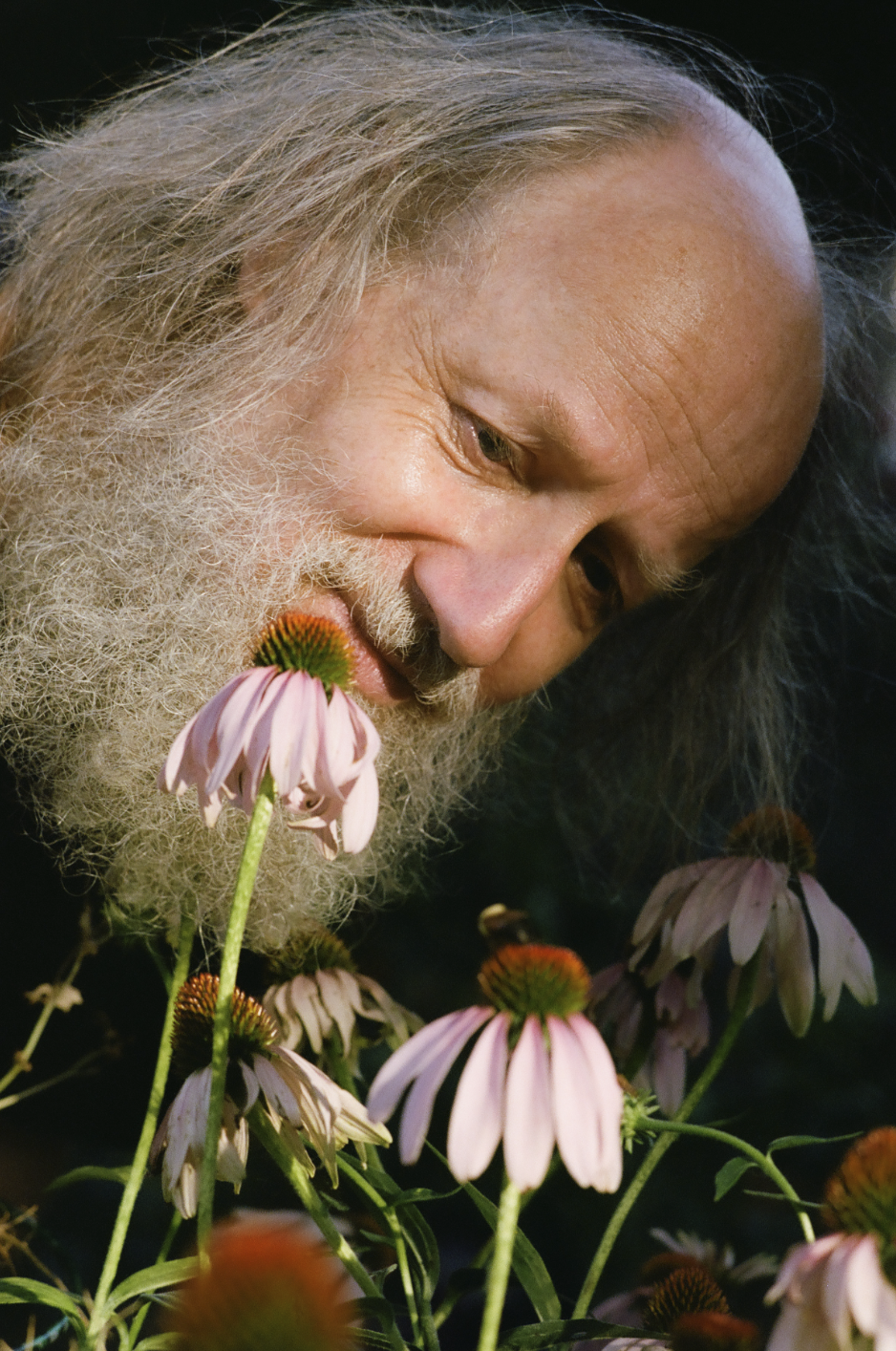

portraits by Jesper D. Lund

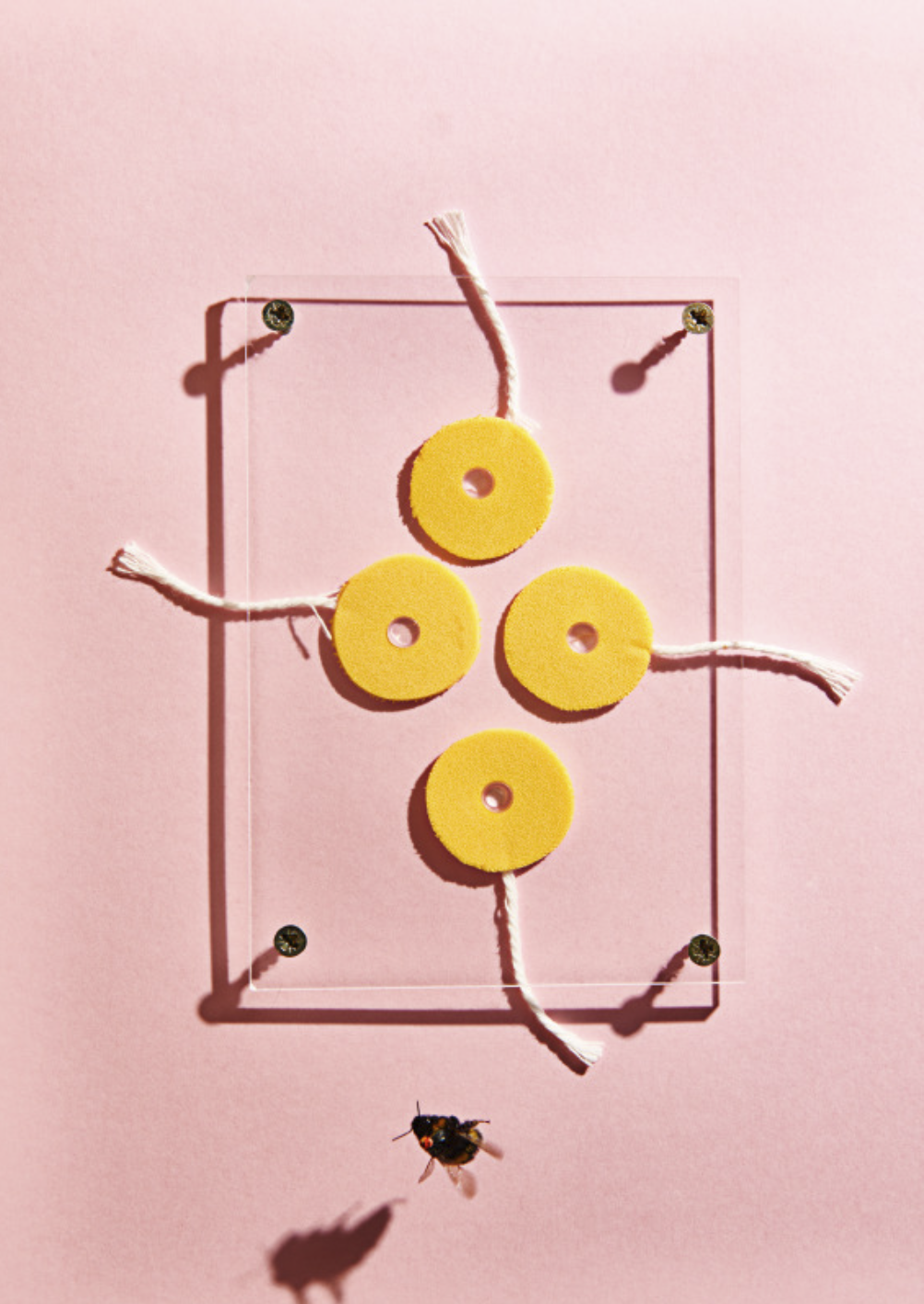

Instinct is biologically hardwired into all organisms. But that doesn’t mean these ancient inclinations can’t be rewired and recoded to adapt to a changing world. For the past five decades, German zoologist Lars Chittka, a widely cited expert on insect sensory systems, behavior, communication, and cognition, has performed groundbreaking experiments with honeybees and bumblebees. Using flower reward models, he has discovered that these insects—once thought to be simple robotic droids of their primitive nature—have powerful emotions that rival humans. Chittka and his team have discovered that bees can use tools, foresee the outcomes of their actions, and they can learn complex dances in the dark of their hives to share the location and distance of food sources. His book, Mind Of A Bee (2022), gathers his deep insights on bee intelligence and looks beyond the hive mind psychology. But what can bees teach us about ourselves?

OLIVER KUPPER What is your definition of instinct?

LARS CHITTKA That's a very good question. As opposed to a behavior that's acquired through learning, it's one you are equipped with from birth, or you're pre-equipped to develop at some point in life. That doesn't mean that it's unalterable, but at least there's something there from the start. We humans often think that we're entirely free from instincts. And we are perhaps freer from instincts than most other animals, but we do have them. There are behavior routines that are common and pre-configured in all humans—so long as they don't have any disorders—such as language: the key ingredient of culture.

KUPPER In your book, The Mind Of A Bee (2022), you have a chapter dedicated to instinct. Can you talk about how instinct plays a role in insect intelligence and emotion?

CHITTKA There is a sense that insects are basically little robots that are entirely pre-configured with everything they need to do in their lives. It is true that there is an amazing repertoire in social insects when it comes to innate behaviors. In honeybees, the construction of a hexagonal honeycomb is at least partially innate. They fine-tune it by learning, but no other animal does it in this form, and to some extent, that is an instinct. Likewise, the ways larvae are provided with food are instinctual. So, there is a very high diversity of innate or instinctive behavioral routines in social insects. But on the other hand, they can learn a lot. And that is the part that's often forgotten. I think people see this as being one or the other: if there's lots of instinct, then these animals might not be able to learn much. Of course, we have discovered that they not only learn things that you might predict, like how to use flower colors or scents as predictors of the sugar rewards that bees find in flowers, or the location of their hive, but they can also learn things that they don't encounter in their daily lives. They can count, recognize images of human faces, use tools, and manipulate objects. They are pre-configured to be really good learners. There are also some good examples where instinct and flexibility come together. For example, they obtain all of their nutrition from flowers, which means that they have to be really good at finding just the flowers that offer the best rewards. This means they have to then learn how these flowers look. Bees can learn to associate flower signals, patterns, and colors with rewards, but they don't know which particular signals these will actually be; they're flexible in that regard. Having flexibility is part of their configuration.

KUPPER When did you become interested in insects, particularly bees?

CHITTKA I've worked with bees since 1987. Even as a kid, I found them fascinating in terms of their weirdness. My mother reminded me recently of when I liked to use my fishing net to catch about a hundred hornets by putting the net over the nest, and then the net over a bucket. I had this whole bucket full of hornets and miraculously managed not to get stung. My parents were completely freaked out by this. Also, I had this single by the Cure, “The Walk” (1983), which featured a big fly on the cover. I was probably about eighteen then. This was a while before I became interested in insects scientifically, which started later in the 80s.

KUPPER In the beginning, you weren’t necessarily focused on insect intelligence or sentience.

CHITTKA For a long time, I was fascinated by the perceptual world of bees—the way that they see the world in completely different colors and through completely different sensory filters than we do, and to some extent, by their intelligence. For example, the numerosity study was quite early actually in my career. That was in the early 90s. At that stage, and actually, for another ten to fifteen years, I didn't yet extrapolate from the work that we did on bee intelligence the question of, hey, if they're that smart, maybe they also can feel something? It was a very different world then. When I was a Ph.D. student in the 90s, I remember discussions with established neuroscientists who claimed that there was nothing to worry about by doing invasive neuroscientific procedures on cats or monkeys, because they weren’t considered sentient. Of course, now there is much more scientific work on animal welfare. In the entire field, we're nudging each other to explore these very different minds from ours.

KUPPER There's nothing scientifically conclusive, but you're pretty close to confirming that bees can indeed feel things.

CHITTKA You're right. There's no universally accepted proof that anything is conscious or sentient. And we see this very prominently at the moment in the media when people are asking the question of when artificial intelligence systems could be sentient or conscious. It's not an easy question. We have to rely on probabilities and common sense. For anyone with a pet dog, if you know your animal well, it becomes quite obvious that there is something going on in their heads—they're not just reflex machines. But there are still people out there who claim that the human animal is the only one with consciousness. But with bees, as you say, like with other non-human, non-speaking entities, we still have no certainty. But from the probabilities that we see across a range of different experiments—not just psychological or behavioral studies, but also neurobiological and hormonal ones—it seems quite likely that there are some emotions.

KUPPER And it's impossible to know what those emotions are. However, it's still interesting to speculate.

CHITTKA As you suspect, it's very hard to answer that question. Even in humans—let's say we identify a piece of music that we both like, we might actually feel the same thing while we're listening to it, but it's very hard to compare such things. It’s even more difficult with an organism that can't verbally comment on what it's experiencing.

KUPPER But bees have some kind of language. Can you talk a little bit about the language of bees?

CHITTKA The communication system of bees, of course, is fantastically alien. They communicate through stereotypical movements, or a dance. They do this on a vertical surface in the complete darkness of the hive. They can't see each other, so they have to feel each other doing this dance. And the dance language informs other bees within the hive of the coordinates of a food source. They are dancing in a roughly figure-eight-shaped movement pattern again and again. Where the two lines cross over on the number eight, there is sort of a horizontal section where the bees run straight ahead before doing a semi-circle to one side, then a semi-circle to the other side. But this central straight run is the most informative bit. The angle of the run is relative to the angle of the food source relative to the sun and the hive. So, if that run goes straight up before doing the next half circle, that tells other bees to fly in the direction of the sun. So, up means fly to the sun. If it's straight down, that tells the other bees to fly opposite the direction of the sun. And let's say if it's 90 degrees to the right of gravity in the darkness of the hive, that tells other bees to fly 90 degrees to the right of the sun. The longer this run, the further away is the food. So, there is a kind of symbolic indication of the direction and distance. And to come back to the overarching theme here, this is of course an instinct that is on display. No other species of animal does anything even closely similar. Back to the dichotomy between instinct and learning, just a few months ago, there was a new study that came out showing that honeybees have to learn precision in their dance. If they don't get the opportunity to attend other bee dances while they're very young, they still display the dance language, but it’s quite a messy dance and not very accurate.

KUPPER Our relationship with bees is ancient, which makes them even more important to understand. Can you talk a little bit about our history with bees and human civilization?

CHITTKA Most people are now aware that bees are important because they pollinate our crops and our pretty garden flowers. But that's a perspective only through utility, of course. But the other thing that they provide for us is sweetness by way of honey. For many millennia, before you could go down to the convenience store to buy a bag of sweets, the sweetest food was honey. And people have known this for a long time.

There are many prehistoric cave paintings depicting humans raiding honeybee colonies. In prehistory, before people came up with the idea of putting bees in boxes, they were stealing from wild colonies because they knew it was such a precious commodity. Beekeeping became a trick to have constant access to honey. This happened in many cultures, not just in Europe. The Mayans had their own species of bees, Asian bees were also kept for many millennia, and then in Egypt as well. So, this practice of keeping bees in boxes for honey production is also an ancient one. But on top of that, in many cultures, bees, because of their perhaps complex societies, were revered as deities or something magical. For example, in the Mayan culture, there are beautiful depictions of the bee queen. And there are some people who think that the consumption of energy-rich honey in our distant evolution might have given us the kind of energy that we needed to grow our brains as big as they are. It's a beautiful speculation.

The interesting thing is that, indeed, all great apes also steal honey from bees and many use two sticks to reach into bee colonies to steal honey. Even some present-day hunter-gatherer societies still spend quite a bit of their time looking for honey in the wild. It’s a very precious commodity, and it's been with us for a long time.

KUPPER I've seen footage of people harvesting hallucinogenic honey.

CHITTKA This is in tropical Asia where some species of bees actually do not nest in boxes and can't be domesticated because they're actually very aggressive. They're also huge. They are hornet sized. They have just a single two-dimensional comb, but it's the size of a steam engine wheel. They're huge structures, usually attached to overhanging cliffs or sometimes tall trees. The honey from these colonies is not easy to obtain because you have to climb up and down at great heights. Some varieties of this type of honey are hallucinogenic, but others are just revered for their sweetness. Harvesting the honey involves tying a really flimsy ladder to a tree at the top of a cliff, then climbing down this ladder with no protection. It's part of these professional honey hunters' pride that they don't wear a veil. They're also suspended several dozen meters in the air, under constant attack from these highly aggressive bees holding on with one hand to the ladder, they then cut pieces of comb from these colonies while someone else underneath stands there with a bucket trying to capture, catch the pieces of calm. So, you’re risking your life in multiple different ways at the same time.

KUPPER Industrial beekeeping causes an enormous amount of stress to the hives. Can you talk about almond milk harvesting in California and the damage done to bees that are used as pollinators?

CHITTKA The usage of bees in this sort of big business pollination industry is probably aligned with the outdated notion that they really are reflex machines and there's nothing to worry about. Imagine during the peak of the Covid pandemic, moving the entire US population to Long Island, keeping them all there for three weeks, and then sending everyone back. There wouldn't have been a single person spared, presumably. But that's more or less exactly what happens with migratory beekeeping. A large fraction of North American honeybees are ferried into a very tiny portion of the country where they are exposed to monocultures of flowers, which are also heavily coated in pesticides. So, there's no diversity of floral food. And then, they're brought back to either their region of origin or another part of the country where a different crop is growing. All of this, of course, is extremely stressful. You have seen these reports of colony collapse disorder in the media. In my opinion, this is just basically the result of very inconsiderate beekeeping practices. Your average backyard beekeeper who looks lovingly after a few colonies, typically doesn't have these same kinds of problems.

KUPPER Aside from dismantling monoculture industrialization, what are some of the solutions for protecting bees from these industries?

CHITTKA I think it's fair to say that any improvements in welfare will cost money. If you want to pollinate the California almonds while also taking into consideration the welfare of the bees, then you'd have to do it with fewer bees—with hives that are in the area anyway. It's possible that having a reduced number of bees, and largely local bees, would probably reduce the crop to some extent. Of course, you'd also have to provide more than a monoculture. And you would have to set aside some field margins to grow other wildflowers so that there's more diversity. But I'm guessing farmers won't necessarily like that because it will cut maybe 10% of the area that they're currently using for almond monoculture. The price of your almond milk might go up a bit, but I think that's probably what needs to be done.

KUPPER What's the greatest lesson you've learned from your work with bees?

CHITTKA Well, the big picture idea is that I have more respect for the strange minds of other animals. My journey began really with a fascination for the strange sensory world and the general strangeness of social insects. In the past, people have commented that bees are a bit like magic—the more you draw out of them, the more you discover. And on a discovery-by-discovery basis, it's been a bit like that. When we first found out that bees can count, everyone stood there in disbelief. And that continued when we trained them to recognize photos of humans. And when we first saw them rolling a ball to a destination, and so on. Five years earlier, we wouldn’t even have thought this was possible. There have been lots of really rewarding things that we've had the fortune to see.