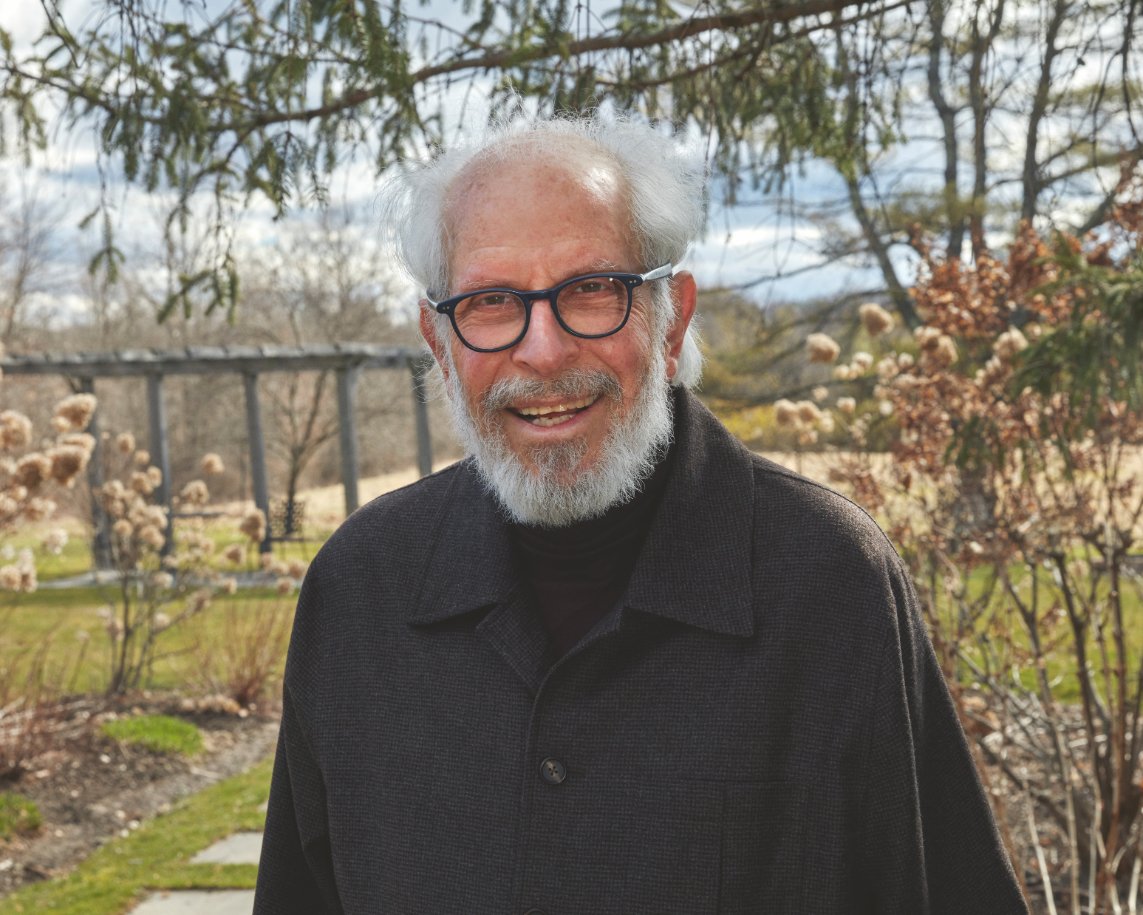

photography by Roe Ethridge

During the early days of the pandemic lockdowns, the legendary photographer Stephen Shore set out with a drone and captured America from above. A direct evolution of his famous mid-century topographic surveys of anthropogenically altered landscapes at street view, rendered in the rebellious realism of color, these new aerial expeditions captured the collective out-of-body experience of a global crisis. With a preternatural ability to train his camera to see the minutiae of the quotidian, there is always more than meets the eye. Shore’s new images unleash a refreshed and broadened understanding of humankind's tenuous relationship with nature. On the eve of his official departure from his ten-year-long Instagram project, fellow photographer Roe Ethridge visits Shore’s home in Tivoli, New York.

ETHRIDGE In the Topographies: [Aerial Surveys of the American Landscape] book, I noticed there are no sunsets and no sunrises. It's all basically the middle of the day. There’s something about the ordinary, mundane palette that is almost anti-romantic or anti-poetic.

SHORE Well, with drone photography, there are some reasons for it. Because I'm photographing at around 100-to-400-hundred-foot elevation, I don't have foreground material. So, I can't delineate space by having something in the foreground and something in the background. I'm photographing a relatively flat surface out to infinity. So, sunlight and shadows help articulate shapes on the surface. Also, I never photograph looking straight down, becausethat tends to abstract things. In terms of limitations, there are three pictures you can take with the drone: straight down, horizonless at a 45-degree angle, and with the horizon. It’s this game with very interesting visual restrictions. The other thing I love about the drone is that I don't know what is outside the frame. The drone is half a mile away from me, but I'm seeing exactly what's in the frame. If I move the camera over a little to the right, I don't know what's coming in. It's a completely different experience than making the visual analytic decisions that I would make on a street corner.

ETHRIDGE When you have that Olympian view rather than the street view it tends to feel more detached. The mess is sort of cleaned up because of the distance, but at the same time, it's like, oh, but we're just so small.

SHORE I like that idea of the Olympian view because it means that there is an entity viewing it; it’s a little more specific than a god’s eye view. Also, it's not aerial photographyfrom the view of a plane. It's a lot closer. It’s the view you get forty-five seconds after your plane lifts off. Things are recognizable, but it’s a different perspective.

ETHRIDGE It also makes me think of the history of aerial photography, like Julius Neubronner’s invention of pigeon photography in the early 1900s. So, seeing this view from above is not entirely new. There are tons of paintings of views from mountains looking out. I also think about The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) by Thomas Pynchon. There’s a character looking over this area of California and talking about how it looks like a circuit board.

SHORE Also, the relationship between natural and man-made features becomes clearer. What happens when a river goes through a city? What does it look like when a residential neighborhood meets an industrial neighborhood?

ETHRIDGE When you're on a street corner, it's like basketball, you have some moves that you can do. With drone photography, it's the pure discovery of this circuit board landscape that must be full of constant surprises. There’s also this mint green palette. Even the cover of the book is minty.

SHORE It's very interesting because I'm teaching a color class now. I haven't taught color in about twenty years. The students todaydon't even think about it being “color photography.” It's just photography. So, I want them to be able to stand back and think about the color. Color can be interesting, but if the picture is just about the color, it's completely uninteresting. That's what an earlier generation, people like Pete Turner, were doing in the ’60s. Young people are putting a frame around the world and not thinking of it as having a color structure. I want them to see the palette and take pleasure in the palette, but not take a picture that is only about the palette.

ETHRIDGE I honestly don't think about it that much at this point. For me, it was also the timeframe that I grew up in, the wallpaper in the house that I grew up in—the ’70s and ’80s palette. I can see it in howI make pictures.

SHORE It relates to something I wrote about in Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography, which is that you work on something as an artist, or even as an athlete, and then you internalize it.

ETHRIDGE I also see you in my work sometimes. I recognize it. So, thank you for that. It’s like how David Bowie said he was an amalgamation. I'm not David Bowie; I'm a hundred different people I took from, like Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol, and this person, that band, that painter. I took one of your little chestnuts and kept it for myself. (laughs)

SHORE That's how all art works. Speaking about Warhol, it hadn't occurred to me what an influence on you he was. But it makes perfect sense.

ETHRIDGE But you were there at The Factory! I read that funny quote where you were saying you and Andy would ride in taxi cabs going Uptown in the middle of the night after the late-night parties. He lived with his mom and you lived Uptown too.

SHORE I was the only one in the group that would wind up going Uptown. There would be activities every night. We'd either go to Chinatown or Little Italy where there'd be restaurants open all night. At some point, people would disperse. Andy lived on Upper Lexington Avenue and I lived on the Upper East Side. So, he would drop me off at home. But we'd have these completely unguarded conversations. The one I remember most clearly was when he was shooting Chelsea Girls (1966), and he decided to show it on two screens. He said, “Oh, Stephen, my films are so boring.” I asked him, “Well, why are you going to show it on two screens?” He said, “Because my films are so boring.” So I said, “Well, why don't you edit? He said, “Well, I don't know how.” (laughs) I had already read theoretical essays in Film Culture magazine about the meaning of boredom in Warhol films. And here I am, maybe seventeen or eighteen, sitting in a taxi with Andy Warhol, who I've read all this stuff about, and he’s talking about how boring hisfilms are.

ETHRIDGE What an experience, dude.

SHORE I was at The Factory on and off for three years. All my closest friends were either in The Factory or Factory adjacent. But Andy would come in every day and work. People had the idea that it was just a bunch of parties. He went to parties, but during the day he worked and he experimented. He tried new things constantly. The first time a video camera ever appeared in my consciousness was at The Factory. I mean, he was working with Billy Klüver at Bell Labs on the mylar pillows. When he was doing the cow wallpaper, he would try dozens of different color combinations. So, I got to see every day what it's like to be an artist.

ETHRIDGE I feel like adolescence is when you get to refine your aesthetic. And what an incredible thing that you were there witnessing this.

SHORE Andy was often impatient with people hanging out there. Once in a while, he put up signs by the elevator saying, “Unless you have business here, don't come in.” But he never enforced it. So, there were people who would come and sit on the famous couch all day staring into space, waiting for something to happen in the evening. But that's not what Andy was about. I felt a kind of connection to the cultural attitude he had. He wasn’t being cynical or derogatory about it—it was just a kind of detached interest in how things worked out in the culture at that moment.

ETHRIDGE Was he doing drugs?

SHORE As you're saying this, I have an image in mind. There used to be a chain of restaurants called Schrafft's. There was one on 57th Street and he would occasionally take me there. He was doing ads for them. It's the kind of place where your maiden aunt would take you for lunch. I remember him opening a beautiful enamel pillbox and taking his amphetamine. At The Factory, we had Brigid Berlin running around with a hypodermic needle sticking people, which is why she was called Brigid Poke. But he took it almost like medicine—in a very genteel way.

ETHRIDGE He stuck so hard to these short, three-word answers. I think it's hilarious. But did he think he was hilarious?

SHORE It's hard to know exactly what my memories are. It was almost sixty years ago and I was a teenager. But as you’re saying this, I remember I was living with my parents and I would have parties sometimes. Andy would come and chat up my father who was an investor. And he got the idea that my father would bankroll The Velvet Underground.

ETHRIDGE No shit.

SHORE The Velvets kept financial books because they wanted to be a grown-up, serious rock band. So, Andy gave my father the books. My father called me over and said, “Look at this. The last entry every day is $10 for H for John's toothache.” (laughs) You can deconstruct that in a few different ways. First, they wanted to be so serious that they would put in heroin as an expense. Second, they recorded it in the books. Third, they justified it by making it for John’s “toothache.”

ETHRIDGE Can I ask you about AI? Is it forbidden in your classroom?

SHORE It’s not forbidden on aesthetic grounds; it’s forbidden on pedagogical grounds. In my class, we start with film. For the first two years, the students only work with film. They have to spend a semester working with a 4x5 camera. We want them to get the basic craft down. AI might be an interesting way of producing a picture, but it's not learning photography. I don't really believe it's creative. The AI work that I have seen that's meant to look creative reminds me of second-rate art fairs where the stuff on the wall looks just like art. If you didn't know any better, it could almost fool you.

ETHRIDGE But it doesn't make a sound. It doesn't have a feeling. It doesn't speak to you. It's mute, in a way.

SHORE But I think it's a lot more complex than a camera. You need to understand its predictability. I can see an artist giving it instructions that will then produce art.

ETHRIDGE It hit me recently: the Renaissance was essentially technological. It came from the idea for the camera obscura. Now, maybe not everyone had a camera obscura so that they could do lifelike drawings of figures in space, but the point was that it was a tool. I love the painting, The Raft of the Medusa, by Géricault. It’s a great example of a reportage painting; a journalistic image of a shipwreck. And I bet he used a camera obscura to draw those figures because they are very posed. It wasn’t like someone doing gestural work in their studio—it was organized. It reminds meof Warhol’s Factory, but maybe instead of drugs, people were hanging around playing lutes or something. But I have used Midjourney for a couple of things. My prompt was a protest in Paris in the style of Roe Ethridge. It's pretty terrible what it gave me,but there are a few of them that I love. It's a bit uncanny. I can't get excited about prompt photography in general, but as a tool, I think it’s really amazing. I'm trying to incorporate it into my next show, but my gallery doesn’t like it. (laughs)

SHORE We referenced basketball before. Do you like basketball?

ETHRIDGE I do like basketball, but I'm more of a college football person, Perhaps because I played football when I was growing up—wide receiver and defensive back, but more defense. Iwas doing a lot of colliding with people (laughs). But then, I fractured a vertebra in my back. That was the turning point for me because I had already been interested in art, but my parents wanted me to be a good, Christian, Southern boy and play football in college. As soon as the CAT scan showed that I broke my back, I was like, “I'm not doing this anymore.” And then, I started taking the codeine stuff and that was my gateway into experimenting with drugs.

SHORE How did you start getting into commercial work, and when did you think about integrating commercial work and artwork?

ETHRIDGE I was living in Atlanta assisting catalog photographers. I had gone to art school and assisting was the only way to make money as a photographer. It was allcatalog work, down and dirty. I have this memory of assisting on a JCPenney catalog and there was a lady from the Texas headquarters over my shoulder yelling to the model, “Smile, honey.” Then, I moved up to New York in ’97, assuming I would be a starvingartist for a couple of years before I tried to get into Yale or Bard at a graduate level. I was making my little conceptual photography projects and showing them at a gallery called Anna Kustera on Wooster Street. I was also assisting a photographer named Jason Schmidt who said I should show my work to Pilar Viladas at the New York Times Magazine. She was like, “Okay, great. I have this textile story coming up. Can you do that two weeks from today?” And I was like, Oh my god, she doesn't know I'm not a photographer—I thought you needed a union card or something (laughs). Then, I had an assignment to do a lipstick story for Allure and the model showed up with her lips totally chapped. And at that point, I was thinking about the delivery system of imagery and how commerce and photography were in this sort of dance. Moreover, pictorialism was pretty taboo—it was like, what does that have to do with Stephen Shore? (laughs) I also discovered Paul Outerbridge who was my spirit animal. And then, Russell Haswell used an image from that lipstick shoot for the Greater New York show at MoMA PS1 in 2000, and that got things going.

SHORE I'm jealous. (laughs) I get one commercial job a year. I just did one for W. It was the fall fashion issue, all accessories, like shoes and bags. And I shot it all around Tivoli.

ETHRIDGE Can we talk about how you used Instagram? You left Instagram last night and posted a goodbye letter to your followers.

SHORE I thought it was time to leave. I've been on Instagram for ten years. In those days, the images were square and I hadn't used the square format in years. Part of the discipline was to post every single day and not do any self-promotion, no greatest hits. The format reminded me of the Polaroid SX-70. Not just in the look, but in the feel. There was a lightness to the SX-70. You could photograph the light hitting the glass and it would be just right. Polaroids weren’t expensive, so you could give them away, which is also like Instagram. After about six years, I found that I began to repeat myself in my work. I was falling into Instagram strategies. I stopped doing it daily, but occasionally I would post other things. At this point, I had over 200,000 followers and I was a mini influencer. (laughs) But I was spending too much time on it—it was becoming an addiction.

ETHRIDGE It has changed for me too. I don't think I ever really settled on a way to use it for myself. I didn't get on until late 2015 because of the square. Before that, I wasn’t able to post rectangular images. But it turned into more of a mix of personal and promotion. It's a ubiquitous part of being a commercial photographer. But I can't get off the thing. I'll be watching TV and then suddenly realize I'm looking at reels while there’s a show on.

SHORE I know—part of me will miss stupid panda videos. But I'm leaving the page up because it was an art project and I want that art project to be archived and seen in the form it was meant to be seen, as opposed to in a book. I felt I needed to post a statement so that people don’t take it personally when I don’t “like” back. I didn't want to ghost anyone