photography by Magnus Unnar

For legendary architect Frank Gehry and artist Charles “Chuck” Arnoldi, the environs of Venice Beach is a tabula rasa. Natural forms and industrial mechanisms, the flotsam and jetsam of a metropolis spilling out westward into the fog, into the sea, and back again are materials and tools for examining art-making and architecture from a completely new perspective. Arnoldi uses a chainsaw to slach and sculpt blocks of wood to create his chainsaw paintings. Gehry’s twisted towers are sinuous, bulbous, and cicumvoluted, mirroring the world around them; ancient, futuristic, and unclassifiable all at the same time.

CHUCK ARNOLDI: I think what drives all artists and creative people is a sense of feeling unsatisfied.

FRANK GEHRY: When 1 graduated architecture school, there were some architects who were practicing in LA, and they came around, sniffing at what I was doing, and they were very negative about me. In fact, after I did the Danziger Studio, they were very negative about that. And while it was being built, Ed Moses was on the construction site. I knew who he was because I used to go to the Monday night gallery openings on La Brea. I knew Ed Moses's work, and I knew Billy Al Bengston's work, and I knew all those artists because I was into their work. Ed was friendly, and he was an artist I liked. And the architects were unfriendly and complained that I wasn't good. So, I thought, well, what do I need them for?

CA: You were thinking more like an artist than an architect. You weren't trying to fit in with those guys, you were trying to make a personal statement.

FG: Well, I didn't know that I was trying to make a personal statement.

СА: No, you didn't know that, but I think part of hanging out with the Venice guys, the aesthetic and that attitude, you liked that because there was a kind of freedom to that creativity and that experimentation. You felt validated.

FG: Well, experimentation and freedom, yes. But the images were staggeringly beautiful. I mean, look at Billy's paintings. They are beautiful. And Larry Bell, messing with glass. That hit close to home because I was doing the Joseph Magnin department store and I had to use a lot of glass. So, I called Larry and asked him for his help on how to hang the glass.

CA: I remember when Larry redid his bathroom. He put in a new shower and a toilet, and he did all this plumbing, and he loved the way the pipes and everything looked. Instead of putting Sheetrock down, he installed glass so you could look at the plumbing! All of us guys would rent storefronts or lofts, and we'd need a white wall, but we couldn't afford to put Sheetrock on, so we'd leave the two-by-fours visible. And I think you could see that there was something nice about leaving the structure visible. It had a beautiful integ-rity. Plus, it was an aesthetic move that all those other architects hated. They couldn't do that if their lives depended on it. (laughs)

FG: Well, it had a relationship to Russian constructivism too. It resonated with me, the whole vibe of Billy and you, Larry and Moses. I especially gravitated to Moses. I don't know why. He tried to hire me to remodel his house, and then when I told him it was $300 in fees, he said forget it. (laughs) But he liked the Danziger Studio, so he copied it on the beach right next to Gold's Gym.

OLIVER KUPPER: What do you think it was about Los Angeles? All of you guys come from these middle-class backgrounds and gravitated to this city, not for the glamor, but for the blank slate quality of it.

FG: I was brought here by my family. I didn't have a choice.

CA: I came from a dysfunctional family in Dayton, Ohio. I thought Dayton was the center of the universe. I'd only left twice, once to go to Kentucky, once to New York City when my father's father died. My father escaped Little Italy because they referred to Italians as wops, and he was trying to avoid that. He was a womanizer, an alcoholic, and a gambler, and he left us when i was in the fourth grade. Then, I got in some trouble in high school and they were going to put me in a foster home, so I called him. He lived in Thousand Oaks and he let me stay with him to avoid foster living. When I got to California, I'd never seen a freeway, never been on a jet airplane, never seen the ocean. It looked pretty damn good. All of a sudden, Dayton didn't seem like the center of the universe. I got in trouble and they sent me back, but a couple of days after I graduated from high school, I got in my car, got three of my nastiest buddies, and headed back to California.

FG: I never heard that story.

CA: The details are kind of interesting, actually. (laughs) It's a complete accident, and one of the things that amazes me, I barely got through high school. I spent about eight or nine months at Ventura Junior College, I spent about a week and a half at Arts Center-I got a scholarship, they never gave one before-I spent about eight days there and realized it was bullshit, quit, went to Chouinard for six to eight months, quit there. So, despite all that, no education, no degree, I've had this wonderful life-mostly because of meeting people like Frank, Larry Bell, Ed Moses, Kenny Price, and Billy Bengston. It was like this dream came true. But the great thing about these guys was the materials they were using. Bengston was working with lacquer on Masonite. Then Frank Stella and all these guys in New York thought, "God, that's a good idea." All these people with resin and glass, and doing shit that is not on the list. And that's what you have done for architecture. I think, inadvertently, you realized, shit, any material's good: corrugated fucking iron, chain link fence, what's wrong with that? It's great! Two by fours, all that had to do with these Venice artists going, "I'll make paintings out of fucking tree branches or I'll make glass boxes." I mean, if you thought of that out of the context of the art world, what the fuck is a glass box? (laughs)

FG: (laughs) Well, my choice of materials always had to do with the projects being small and not having budgets. So, I had to use whatever I could, and that's what got me into corrugated metal. I liked it aesthetically, this galvanized stuff, and then the chain-link was fascinating to me because it was produced in quantities that are bizarre. I went to a chain link factory Downtown and spent an hour there one day, and they had four people running a 200,000-square-foot warehouse with only one machine making chain link. And in one hour the guy told me they made enough chain-link to cover one lane of the freeway from Downtown to Santa Monica. And I thought, if my artist friends can make art out of anything, and architecture is art, I can make architecture out of anything. It was powerful stuff. I was also inspired by Gordon Matta-Clark who was slicing buildings in half. Or Robert Smithson who did Spiral Jetty [1970]. I was doing the Concord Pavilion and I did the space with earth. It was starting to be a spiral, so I called Smithson, sent him some pictures of it, and said, "I invite you to make this exterior. It's just starting, and you can do whatever you want." He said, "I'll call you next week." In between that time, he got killed in a plane crash.

CA: One thing that was kind of interesting-a lot of it has to do with Gemini G.E.L. Gemini brought all those New York artists out to LA. Frank Stella, Jasper Johns, [Robert] Rauschen-berg. I never thought of them as famous, great artists, they were just these great guys from New York, and they would actually communicate with you. I remember Rauschenberg once said "You know what's really interesting? You and I both make art out of junk." (laughs)

FG: I remember they loved you. And they were nice to me, so they must have liked me too. Slowly, for me, over time, the LA and New York thing started to mix. I remember ending up at the Factory up in Warholville with [John] Chamberlain, and Ultra Violet was his girlfriend.

CA: Well, Christophe de Menil was great too. She'd have a dinner party and there'd be ten of us there. Then, there'd be three, four limousines, then four, five, six other people would come in, and there'd be a couple more limousines. As soon as the dinner was over, all the limousines would be like a train out to Studio 54, and they'd just part the ropes and we'd all go straight in. Jasper Johns or Rauschenberg would say, "Hey man, come to New York, stay at my place." And it was weird because they kind of had this reputation of being these assholes, but Chamberlain just loved hanging out with us Venice guys.

FG: I took him sailing one day. Do you remember Michael Asher, the artist? He was also a great sailor. I had a Cal 25 sailboat. Michael and I decided to go sailing on the windiest fucking day-storm warnings and everything. So, we got geared up, and we're driving down Main Street or Pacific, we get to the corner where Larry Bell's studio was, and Chamberlain was standing there dressed in a suit. It was raining. I stopped and said, "Well, what are you standing out there for?" And he said, "I'm ready to do something. Where are you guys going?" I said "We're going sailing. Want to come?" So, he got in the car and we got to the boat. It was the wildest ride in the ocean I've ever been on. I mean, it was dangerous. Chamberlain loved it.

CA: He was in the Navy, I think. He showed me his feet one time, and he had roosters tattooed on them because supposedly if you have roosters on your feet you won't drown.

FG: Well, there was something there. A year after we took him sailing, I was in New York, and he called me up saying he had his new boat at 95th Street and whatever. He'd been sailing since he went with us. He went down the coast to Florida and sailed back and forth. He became a great sailor.

CA: I really loved New York. When you're young, it's great. As you get older, you want to escape, but the problem with New York, is if you want a fucking quart of milk, it takes half a day and you're always in somebody's face-confrontations with strang-ers. The thing about California, is you're with friends or people you know, or you're alone in your car, you have time to think, so you don't have to deal with all this crap. There's something super attractive about California. I mean, just the weather.

FG: Chuck, we used to share a studio. In the morning I'd have a coffee, and you would show me a painting by 9:30, 10 o'clock. And I used to go, "It's great," and you'd say, "Yeah, I gotta think about it." And then, I'd come back at 4:00 and you would change it. I always thought it was better, of course, without you changing it. So, I used to try to get you to stop, but that's not in your DNA. You can't do that.

CA: (laughs) Look around this place. When you get a client, they're just excited. They'll have a problem for you, and you'll work out a scheme that takes you six months or something. The client comes in and they always go, "Oh my god, that's great," and you go, "No, it's not ready yet. You have to come back in six months." So, you do what you accuse me of on a huge scale, but I understand you're doing a $300-million-dollar building. Whereas, I've got the cost of materials and a little bit of time.

FG: It's different because I have to go to the building department, I have to go through engineers, and I have a budget, which you don't have.

CA: At a certain point, you were having a hard time with the technology aspect of what you were building. Architecture used to be pencils and T-squares and stuff, and you were doing interesting enough architecture that you got approached by a company and thought, hey, we should computerize architecture. And you were smart enough to go along with this thing. So, if you want to do a building with a million curves in it, it's figured out.

FG: What happened was I was working in Boston and I had a lawyer doing our contract. He was a big guy in the AIA [Americans in Architecture] at the time and I had made a building in Switzerland–The Vitra Design Museum–where there's a curve in the plaster. I was taught to draw those curves using a geometry system that everybody used at that time to make forms. So, I used that system that I was taught, but they built the curve and it had a kink in it. They swore they built it exactly as the drawing. So, we scoured the thing and sure enough there it was: our two-dimensional drawings of three-dimensional stuff had a failure in the system. I discovered that the hard way. So, I called IBM and asked them if they had any software, because they had CAD at the time, which was two-dimensional. We were using that, but it was unwieldy and tough to do, and it still didn't deliver the exact curve. The reason I was interested in curves is that I wasn't happy with modernism or postmodernism. Modernism was rigid, geometric, ninety degrees. Once MoMA's architecture curator, Arthur Drexler, had a show with some really beautiful, seductive premodern buildings, it jump-started the postmodern architecture movement. Within a month or two, Phillip Johnson] did the little building for AT&T, Robert A.M. Stern started doing his stuff, and Charles Moore and Robert Venturi went into postmodernism. They were all going down the rabbit hole and it was very upsetting to me when they did that. I was at a conference somewhere and everybody had twenty minutes to speak, and it was my turn. I got up, I looked at them, all and said "Why the fuck do we have to go backward? Isn't there anybody going ahead? There are cars and boats and airplanes and a lot of movement out there, and you guys are happy doing this? It doesn't fit our time." I don't know where this came from. Then, I said, "Well, if you have to go back, why not go back 300 million years before man, when we were fish? Fish look architectural. If you look at them, they express movement, and we are in a time of movement." That's all I said, then I sat down and shut up. From then on, I started drawing those fish. It did inspire form and I looked at all these Japanese Hiroshige prints. There was so much architecture to be inspired by.

OK: Can we talk about how and where you two met originally?

CA: We met so long ago. The thing is that everybody used to party and hang out together. It was a very small art scene, and the Venice scene was even tighter than any place, so when we had any reason to have people over, we'd always be there. And Frank was always part of the group.

FG: Well, I remember you were declared the youngest, the new guy. You and Laddie John Dill hung out and I was interested in what you were doing. I was always interested in your work, and always couldn't figure out why you'd change it in the afternoon, but I learned to live with that. But when you did the chainsaw paintings, that expression of anger was just visceral. And then, you painted it and took away the anger. Richard Serra's pieces are about anger. They're beautifully composed and fabricated and all that, but there's a lot of anger. He builds the piece and finishes it, and they're beautiful, but they're still fucking angry. Whereas Chuck, you diffused it. And that's your personality. You're a nice guy.

CA: I had a studio in Venice. It was a fluke, I ended up with this big building and Frank needed a place to move his office. One of the guys moved out, so Frank moved his office into the building, and we saw each other every day. We collaborated more than just talking and arguing and stuff. (laughs) But the thing is, we all really suggested things to friends. Like I had a friend, Bill Norton, who was our partner in the building. He directed a movie and wanted to build a house, so Frank got to build a house for him on the boardwalk. He used to be a lifeguard, so Frank built what looked like a lifeguard tower in front of the house.

OK: I think both of your work is uncategorizable, and that's why LA is so interesting. It's an uncategorizable, make-believe city that came from nothing, and both of your work has come out of this milieu. Can you guys talk a little bit about being in that realm? I was reading an essay that Reyner Banham wrote about your architecture Frank, and this was before the Pritzker Prize, but he said, "If people understood your work, maybe you'd be the biggest architect in the world." It's funny to read that now.

FG: Reyner Banham called me after I had finished the Danziger Studio. Esther McCoy was the architectural writer in Los Angeles at the time and she was confused by my work because I did that apartment building that looks like a Monterey Span-ish. This was a time when I was fitting into the neighborhood. That was my trying to make a building that was a good neigh-bor. I was into that. I'm not going to shake up the neighbor-hood, I'm going to make a building that is great and show them how you can keep going. I got whooped for that one. That was postmodernism before anybody heard of postmodernism. After I did the Danziger Studio, they all came running. So, Reyner Banham called me—he came to LA from Berkeley, and he told me he was writing a book, and he wanted to interview me, and I said, "I'm not ready for that."

OK: Maybe we can close things out by talking about the world right now. How do you see yourself as an artist in the world right now? How do you see yourself as an architect in the world that we're in now?

CA: When I got to the art world, I never thought of fame and fortune at all. In fact, when I met all those artists, they weren't famous people. I consider the Rolling Stones and the Beatles famous. But the world today is so driven by the commercial, and I think it's immoral. It's like real estate. When they can sell paintings for $50 to $100 million, maybe 8 to 15 million for a young artist who's, say, in their forties, something is wrong. Because in the old days, you had to earn the position you got to. The great thing about Frank is you can spot a Frank Gehry from a mile away-not that they re all the same-but they're like sculpture, they're a statement unto themselves. It's a form, it's something where you go, "That must be a Frank Gehry." Other buildings might be tasty and everything, but they just don't stand out. Frank, I don't know what you think about contemporary architecture, is it the same as the art world?

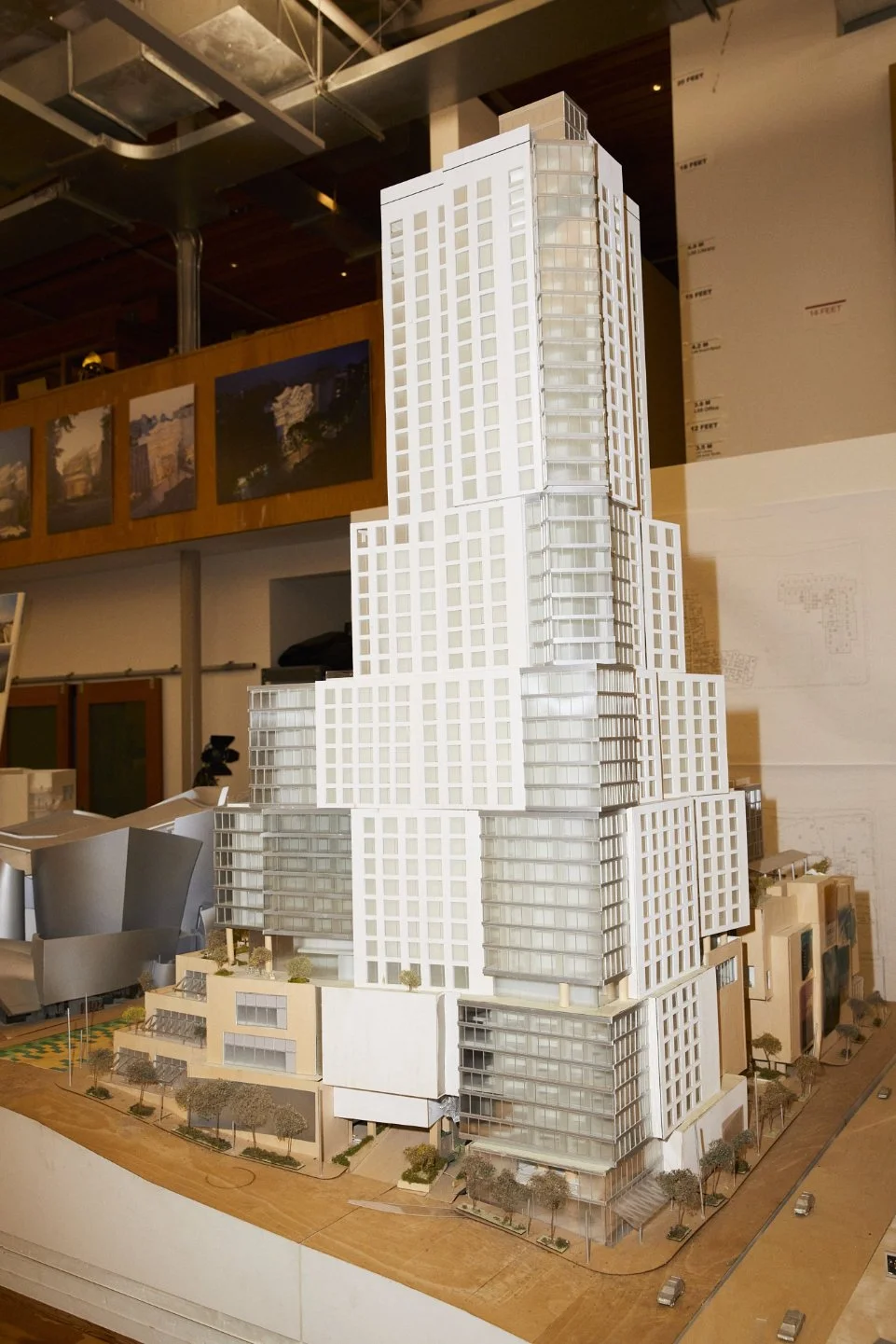

FG: I haven't been paying much attention to the new, younger architects. LA is not as blank as it was. I did the commercial project across from Disney, which came out really great for a commercial project. I'm really proud of that. I had no idea it was going to come out that good. The feeling and the scale and the humanity of it is what I was trying to do and it does work. As an art piece, it's a different story. It's a different connection to humanity. I think that architecture takes itself too seriously, and so does art.