Text by Oliver Misraje

Photos by Michael Tyron Delayney

Illustrations by Isabelle Adams

It’s 10:30 PM and we’re much deeper into the Mojave than where we met Ken Layne at the Joshua Tree visitor center. It’s full dark. No stars—yet. Clouds drifted in an hour ago, making for bad UFO hunting weather, but if we drive far enough east, we might beat the overcast. Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.2 is playing from the speaker system in his Subaru. “What’s that?” Ken Layne interjects suddenly in his characteristic sandpaper drawl, “It’s very low, it just went out.”

“I saw it,” says Isabelle Adams from the backseat. She’s an LA-based painter and inaugural member of our off-brand Scooby gang. “If you look in the corner near the base of the mountain … oh wait it’s gone.” Michael Tyrone, the photographer, and I strain our eyes to no avail.

“Was it blinking?” He asks, "if it blinks, it’s probably just a navigation light for aircrafts.” He tells us that most sightings of unidentified flying objects are easily explained; extraordinary things rarely happen when you’re looking for them. Twinkling lights are usually just planets. Stationary orbs that blink out after ten minutes are probably military flares (the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center carries out frequent training drills nearby). Then, there's an aerial phenomenon that isn’t as easily explained, “now and then you see something that simply doesn’t make any sense,” he says, “It’s just silly. It’s not dramatic.”

The third kind of sighting (not to be confused with the Hyneck’s scale commonly used by ufologists) are experiences so awesome—in the biblical sense of the word—that you brush up against something ephemeral and undeniably original. Ken has only experienced this once in his life. In 2001, he was driving down Highway 395 with his then-wife in the passenger’s seat when they noticed a light to the north. It seemed innocuous enough, though something felt off. It moved erratically as though untethered from the horizon. The pair debated what it might be for a few moments, when suddenly and without warning, it was gone and in its place a large black triangle, about 200 feet in diameter. Its corners glowed and a spotlight emanated from its center, illuminating the desert floor below with a brilliant intensity, like a “great, unblinking eye” as Ken described it. He hit the gas. The car got nearer. But when he pulled to the curb and rushed out— the mysterious triangle was gone, vanished without a trace or residue to affirm its presence.

Life above a fault line can be a perilous thing—the threat of the San Andreas fault swallowing the county notwithstanding, the constant tremors seem to inform the psyche of those living above it. Ken is something of an antenna himself for the murmurs and reverberations of California’s inland desert, picking up and broadcasting tales of the uncanny to all the lot lizards, and hippies, and hipsters, and occultists who color the landscape. On his radio show and newsletter, The Desert Oracle, for which he has attracted a cult following since its genesis in 2015, Ken adopts the cadence of an old time-y creep show host, but with a folklorist’s edge. His stories—whether they be about haunted petroglyphs, the Yucca Man, or missing tourists—are about the cryptids as much as they are about the people who encountered them. It’s the vestiges of his past career as a journalist, including a stint as a crime writer in Oceanside, that appeals to his more skeptical readers.

Ken grew up in New Orleans but moved to Phoenix when he was in middle school. His formative years in the Sonoran Desert are visible in the structures of his narratives. They unravel like a meandering stroll in the desert—winding, and seemingly aimless, until you reach the open expanse of a question mark where you were expecting a period. It’s that big, looming uncertainty that is so tantalizing; the suggestion that maybe, there really is something out there lurking in the dark. “Storytelling, which is the oldest form of human entertainment, probably after sex and mushrooms, has to involve set and setting,” Ken says to us after pointing out the rusted exoskeleton of an incinerated car next to a sign welcoming us to Wonder Valley, “To tell a story by a fire is one of the most primal things, a perfect setting. There’s not a lot of hyperbole in a good campfire story, you should just tell the narrative and the place, and everybody’s personal experiences all conspire together to make something greater than the parts.”

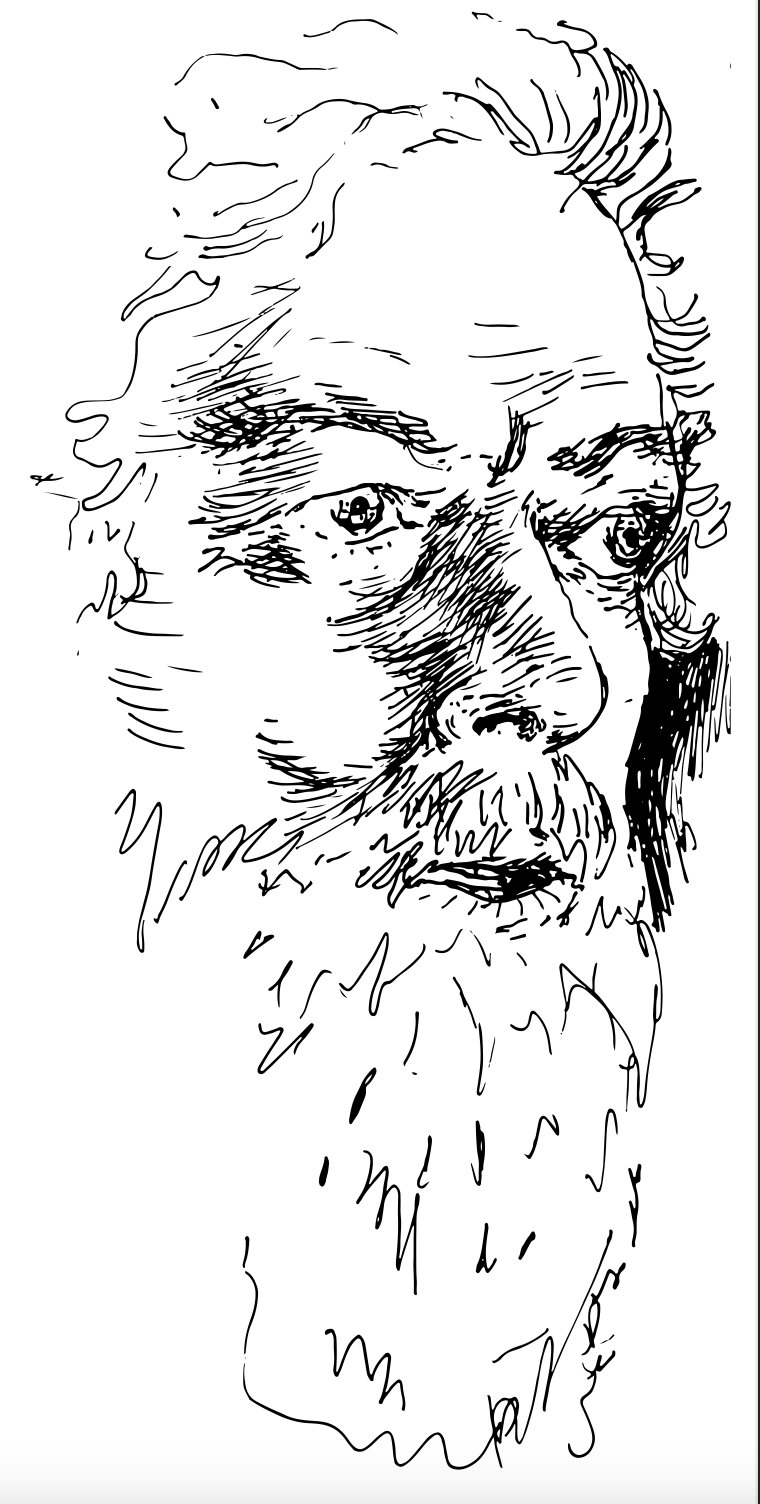

We reach a roadblock. Michael suggests we utilize the dim glow of the traffic cone to take some portraits. “We are now officially in the wilderness,” Ken says, stepping out to the dazzling, unobstructed spine of the milky way. Izzy and I take turns holding flashlights pointed towards Ken, casting ominous shadows on his face. He’s a natural model. No longer Ken Layne, this is the Desert Oracle in action. His gaze twinkles with a discreet intrigue that softens his otherwise shrouded face. The alter-ego has itself become an integral part of the mythos of Joshua Tree; an archetypical wandering stage that retains fragments of his heroes, like Edward Abbey of The Desert Solitaire and Art Bell. Between camera flashes, Ken tells us about his closest companion, a German Shorthair Pointer dog. It’s a breed of hunting dog that are usually cast away for their aggression, but Ken is drawn to outcasts.

As we get back into his car, I ask Ken about that aforementioned journalistic scrutiny. He pauses a beat, then says, “a story, warts and all, is much more interesting than the kind the UFO fanatics tell, which is something like ‘Oh, a person of the most unimpeachable character, never touched liquor, blah blah blah.’ Like, c’mon . He’s already sounding really weird. When stories gauge the reality of the human condition, they’re naturally more real. They resonate. No one’s trying to sell you anything along the way. No one’s trying to convince you the government is covering up aliens eating strawberry ice cream in an underground base somewhere.”

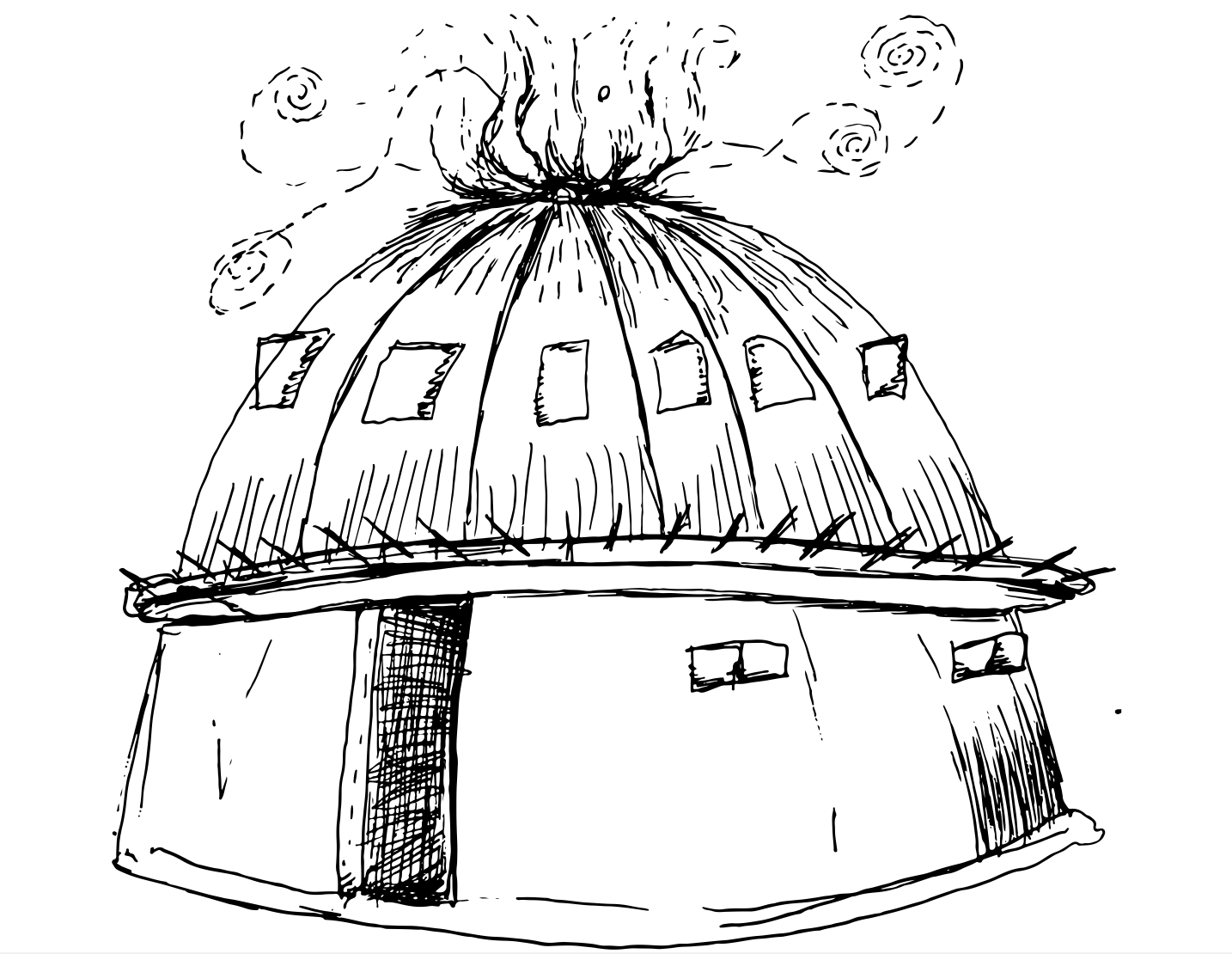

“Weren’t you on Ancient Aliens?” Michael asks from the backseat. Ken laughs. “Touché. I’ve repented down in the river for that.” And in his defense, he was only in two episodes. One was a history lesson on the Integratron out in Landers, a cupola structure built by aviation engineer and ufologist George Van Tassel, allegedly capable of generating enough electrostatic energy to suspend gravity, extend our life spans, and facilitate time travel. The other segment was a cultural debriefing on the viral meme about storming area 51 to see dem’ aliens.

Fans of The Desert Oracle often occupy a more cosmopolitan demographic, which some journalists have attributed to the “escapism” of his stories. Escapism is a misnomer. The appeal lies in the return to meaning and a resistance to the sinking feeling of post-modernity that we are losing our archetypes—the haunted house at the end of the street, knowing how to differentiate between good and bad winds, which roads a ghostly woman in white frequents.

I grew up in Sun City, a small town in the desert not terribly far from Ken’s haunts. Like him, my dispositions were shaped by the landscape. I discovered The Desert Oracle my senior year of college while working on my thesis, a hauntological study of our local monster, Taquitch—a shape-shifting, child-eating, “meteor spirit” that prowls the San Jacinto Mountains. Taquitch originally appeared in the mythology of the Payómkawichum tribes who still occupy the area, but legends persist today. I was interested in the ways these paranormal stories were a metaphorical vehicle for sociological phenomena. The Inland Empire is riddled with poverty, addiction and despair, and as a result, experiences higher rates of domestic violence and lower child expectancies. It is haunted either way you look at it.

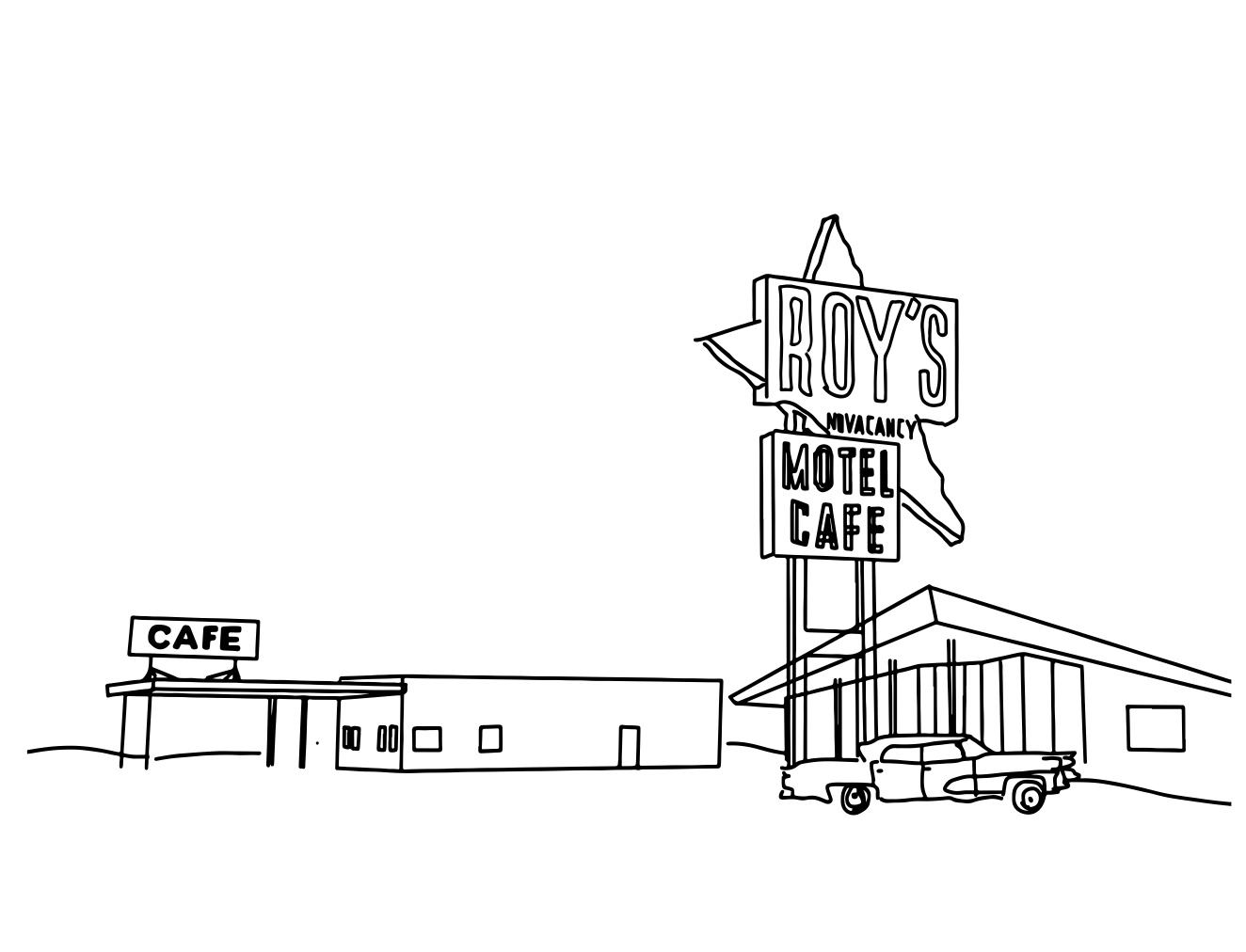

Ken talked about Taquitch in the twenty-first episode of his radio show. On our way back to Joshua Tree, we make a stop at Roy’s Motel and Cafe, a defunct relic of Googie architecture. While poking around abandoned motel rooms, we discuss the merits of the hauntological approach. Ken ultimately disagrees with the notion of trauma as a prerequisite for a haunting; some things are older than us and more original to this world than we can comprehend. Even so, he is well aware of the ‘cultural dressings,’ as he puts it, often applied to paranormal phenomena. Take UFO sightings—while observed across cultures since time immemorial, explanations of such often reflect the dispositions of the times. He tells us that there’s nothing actually connecting UFOs to extraterrestrials. The theory appeared in conjunction with the Cold War and the space race. During the industrial age, many explained them as the inventions of eccentric, steampunk robber barons. In Medieval times they were thought to be witches with lanterns hanging from their broomsticks.

The fault line that the Inland Empire (which includes Joshua Tree) sits upon, demarcates it geographically, as well as symbolically. To the Western imagination, it is the ultimate nowhere; a psychic space to project its dreams, ideals, anxieties, and nightmares. The idea of the desert as barren is a colonial project, one that has historically been used to justify its desecration since the frontier period. We’re driving through Amboy when Ken tells me, “one of the biggest misconceptions about the desert is that it’s barren. Desert means wilderness. It’s Greek, borrowed from the Latin deserto. Not arid, not barren, but untamed, uncultivated wilderness. It’s where Pan ran around in the primal wilderness. Ancient Greece was the desert. Civilization is born in the desert.” The Desert Oracle repopulates the landscape. While his documentation of hibernating birds native to the Southwest might seem mundane in comparison to shape-shifting monsters, it's where his Transcendentalist musings are most poignant, revealing a gentle, more meditative side to Ken.

Cultivating a sense of awe for the desert is an important part of its conservation. Advocates for environmental personhood also seek to reimbue the landscape with soulfulness. In 2020, tractors in Arizona leveled the earth for the construction of the US-Mexico border wall, unceremoniously demolishing 200-year-old Saguaro cacti in the process. The Saguaro are sacred to the Hia-Ced O’odham tribe, whose ancestral grounds lay 200 yards away from the site. After fiercely resisting the construction, the tribe successfully passed a resolution affirming the legal personhood of the Saguaro. In an op-ed piece for Emergence Magazine, tribal member and activist Lorraine Eiler wrote, “When something is acknowledged as a person with rights, it is much more difficult to overlook the infliction of harm. This resolution has brought us one step closer to bridging our spiritual understanding of how to sustain life with the practices of the dominating culture.”

We’re driving down Amboy Road when Ken stops the car. He pulls the keys out of the ignition. The road is empty, beyond the receding taillights of a distant car far behind us. “I had us meet up on a weekday because I wanted to avoid the traffic going into Death Valley. You lose the mystery when it’s filled with Audis.” He tells us to watch the taillights until they disappear beyond the bend. We oblige. After several minutes, the lights blink out.

“It’s a long way, right? About ten or eleven miles. One night, I was coming back from Death Valley and I was the only car on the road. Moonless night just like tonight. I’m doing 65 or something. It’s a 55 limit so you’re always watching for that occasional CHP dispatch. Suddenly, I see what seems to be a car’s lights appear, and what I notice in my rearview, is that it is racing, like Roadrunner, Coyote cartoon speed. I'm driving, and my first thought, of course, is it’s a cop, so I slow down, and it keeps on coming up-up-up-up,” Ken says, stressing the word up like a rapid-fire machine gun. “It’s like the brightest high beams, and it comes right up to my ass. So now, I’m thinking it’s just some jackasses coming back from Vegas. I start slowing down to let the car can pass me. I’ve come to a complete stop. And it’s still there, just blinding me. I turn around to look out, and this is the first time it occurs to me: the lights aren’t attached to anything, they're just floating there, and I have just a moment to try and rationalize it, when the lights retreat at the same speed they came up ZUUUUUUUUERRR. It doesn’t turn around. No sound. No nothing. All the way down, until it blinks out in the end.” Ken lets the story dangle in the air for a moment. Beethoven’s Symphony no. 13 opus. 135 plays quietly from his sound system, lending itself to the eerie atmosphere.

We stop at Out There Bar in 29 Palms for a nightcap. It’s neon-lit inside and the walls are painted with murals of varying cowboy iconography. The bartender and several straggling patrons look at Ken with a glimmer of recognition. I forgot my ID card at home but the bartender winks at us and says she’ll make an exception just this once. While Izzy and Michael go head to head in shuffleboard, Ken and I drink tequila at a table and talk about the Puritan origins of the environmental movement; how theologians like Emerson and Thoreau saw corruption in all things made by man, so they glorified nature as the true expression of god. When I mention that my father was a pastor, he tells me, “There’s nothing better in the world for maneuvering through life than a semi-educated, literate redneck.” Afterwards, the four of us take pictures in a photo booth (Michael sits on Ken’s lap) then Ken drives us to the Joshua Tree Visitor Center where we left our car. On the way, we share stories of our respective encounters with the Otherworldly. Michael tells us about a night in Griffith Park when he saw a coyote stand upright on its hind legs and run off into the chaparral. A few weeks later, the tale of the Coyote Man appears in The Desert Oracle.

As Izzy drives us home to our remote outpost in Landers, the absence of Ken is palpable. Peggy Lee croons on the radio and the shadows cast by the Joshua trees look a bit more animated; the world a bit more occupied.