Text by Adam Lehrer

I recently interviewed an iconic musician who had a personal relationship with Nick Cave in the ‘80s (not going to say who). This artist felt like Nick Cave’s work had grown stale and safe since his time in The Birthday Party in the early ‘80s. I nearly choked on my chicken avocado omelet. I couldn’t help but detect a hint of jealousy. How could a rock musician of a similar era not be jealous? Nick Cave is arguably the last great rock superstar ARTIST. We have “rock n’ roll artists” of course, but most of them operate so deep in the music underground that the most stardom they could hope for is a Pitchfork review and some free beer after a show. And there are superstar artists: your Kanye’s, your Beyoncé’s, your Frank Ocean’s, your Kendrick’s, etc.. But finding any worthwhile rock music amongst mainstream culture is a fool’s errand. It doesn’t exist. Rock music is not the important pop cultural force that it once was and it never will be again.

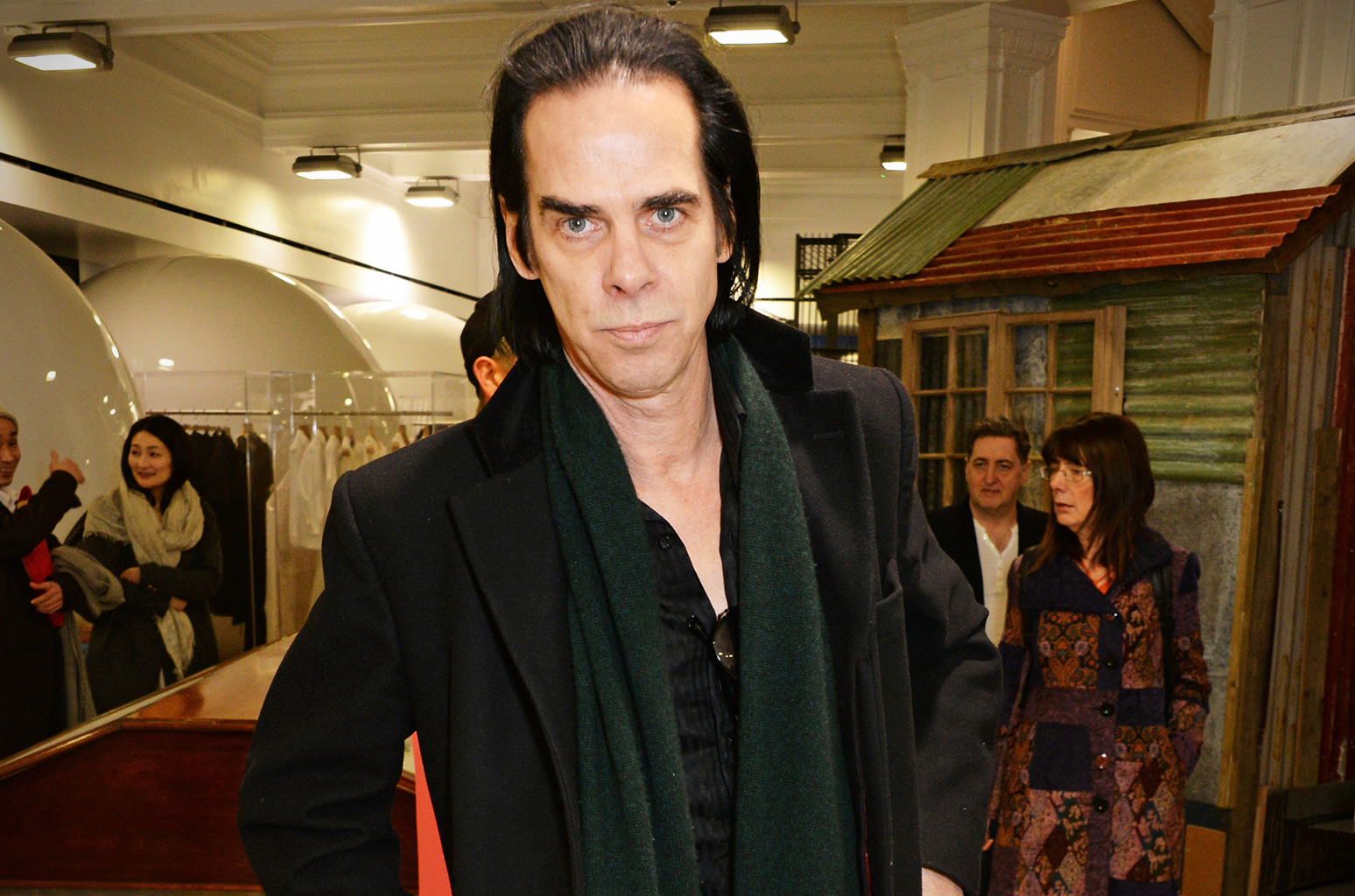

And then you have Nick Cave: world famous, constantly written about, high profile indie rock romances with PJ Harvey and Kylie Minogue, and refusing to waver in his commitment to artistic expression and poetry. Not only has Nick Cave’s output not grown stagnant, it’s grown stronger with each release. Some underground music fans would rather their heroes remain the rail thin, anti-fashion chic, drugged out, intense freaks that they were in their youths. And of course, some artists do their best work during their angry and vivacious ‘20s (unless of course you think ‘Chinese Democracy’ was a good album). Nick Cave, on the other hand, has seen his art evolve with him. Coming onto the late ‘70s London post-punk scene from Australia with his first band, the art damaged bluesy noise rock band the Birthday Party, Cave was a goth rock icon upon first glimpse: tattered clothing, skinny, pale, dark eyes, and a messy tussle of thick black hair. But Cave matured, and his music with The Bad Seeds would grow more musical and in some ways, more experimental. Eventually cutting heroin from his diet, Cave’s ideas grew more nuanced and detailed as his life stabilized with fatherhood and marriage. One of the greatest songwriters of the last thirty years, Nick Cave has never remained still. Oddly, Cave is now more Leonard Cohen than Iggy Pop, more Neil Young than John Lydon. For Nick Cave, maturity doesn’t denote an acceptance of the banal. Count in the fact that he’s a published novelist and screenwriter of brutal Western film Proposition and the adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, there are very few artists on Earth who have been able to build an aesthetic as definitive as the one Nick Cave that has built.

2016 has been the best year for music that I can remember in my entire life. From the top of the mainstream to the bottom dwellers of the underground, every single day I read about a record on The Quietus or Resident Advisor or Pitchfork that would blow my mind later that day. Now consider that, and consider the fact that Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ recently released Skeleton Tree, the band’s 16th record, is easily in the top five of the best albums released this year and very possibly the best record of Nick’s or the Bad Seeds’ careers.

We all know the tragic circumstances surrounding the recording of Skeleton Tree. In 2015, Cave’s son Arthur (a twin to brother Earl, both of whom appeared in the Cave documentary 20,000 Days on Earth, watching DePalma’s Scarface contentedly in bed with dad), who was born to Cave and his wife Suzie Pitt in 2000, plummeted to his death in a freak accident whilst hiking near their home in Brighton, England. Death and loss have always floated above Cave’s poetry like inevitable harbingers (Pitt has expressed a belief in her husband’s ability to write prophetic lyrics, on previous masterpiece Push the Sky Away Cave sings on the track ‘Jubilee Street,’ "I'm transforming / I'm vibrating / I'm glowing / I'm flying / Look at me now / I'm flying,” there’s no way to listen to that song now without thinking about the tragedy that would soon follow its creation). A noted agnostic, Cave seems to have doubts about god and religion but welcomes hope that there could be such a creator. His morbid fascination with death, both natural and murderous, have been loaded with pathos and conflict since the beginning of his career. On Skeleton Tree, Cave has to confront the most powerful grief a man can endure from the first person view point. These lyrics have no protective distance.

Musically, Skeleton Tree plays like a building on the sound that The Bad Seeds developed with Push the Sky Away: sparse, experimental, deeply musical, and washed in ambient sound. To look at the evolution of Cave’s career one has to examine the chronological list of his most important collaborators. The Birthday Party was largely birthed out of Cave and guitarist Rowland S. Howard’s deep love of the blues, Iggy, and The Damned, and the band dissolved when Cave wanted to take his sound further out (to his credit, Howard’s solo career is one of the most irresponsibly underrated collections of blues punk in the history of rock music). The Bad Seeds were born out of Cave’s emerging friendship with Einsturnzende Neubauten founder Blix Bargeld when the two were both living in Berlin. Bargeld, a lover of komische bands like Neu and Can as well as experimental music, defined The Bad Seeds as a band informed by deep musicality and experimental tendencies as much as it was by blues and rock heritage. But after Bargeld left the band in 2003, Warren Ellis was able to come to the fore of the band. Warren Ellis, a virtuoso guitar and violin player, multi-instrumentalist, and founder of Australian instrumental rock band Dirty 3, has proved to be Cave’s artistic soulmate. In 30,000 Days on Earth, we see Cave laying down the lyrics to “Higgs Bolson Blues” while Ellis strums a beautiful guitar pattern. Cave starts swaying and dancing subtly to the music, realizing just how fucking good it is. That scene cuts to the heart of their partnership, a partnership that has produced the beauty of The Bad Seeds, the primitive thud of Grinderman, and the expansiveness of their film scores.

Ellis’ watermarks are all over Skeleton Tree. The electronic swaths of ambience that cloak Cave’s voice in mysticism, on tracks like ‘Magneto’ and ‘Rings of Saturn,’ that’s Warren’s KORG synthesizer. The lush string arrangements on ‘Jesus Alone’ and ‘Skeleton Tree’ are Ellis’ composition at its apex. The duo of Cave and Ellis has become the Bad Seeds’ focal point. Jim Sclavunos, Martyn P Casey, Thomas Wylder, and newer guitarist George Vjestica recognize this notion, and this band has never felt like such a well-oiled machine like it does on this record (with a line-up that has been playing together for some 16 years now, that really is remarkable).

Cave’s poetry has largely been founded upon the grief Cave experienced when his beloved father died when he was only 19. But all those songs have been written with a hindsight view of that loss. Arthur died in the middle of this recording. It’s impossible to not hear pain dripping from the cadences of every uttered syllable on this record. Are we projecting these emotions as listeners and as lovers of Cave the man and the artist? Cave is one of those artists that feels like your friend when you really get attached to his music and his words, and empathetic viewpoints are easy to take when it comes to this kind of tragedy. But no. I think someone who knew nothing of Cave or the accident would listen to Skeleton Tree and know that this man singing was bleeding from the heart. At one point on the song Girl in Pain, Cave sings, “Don’t touch me.” He is inconsolable. He doesn’t want to be consoled. But he still wants to sing.