Interview by Oliver Kupper

Portrait by Summer Bowie

Install images courtesy of UTA Artist Space

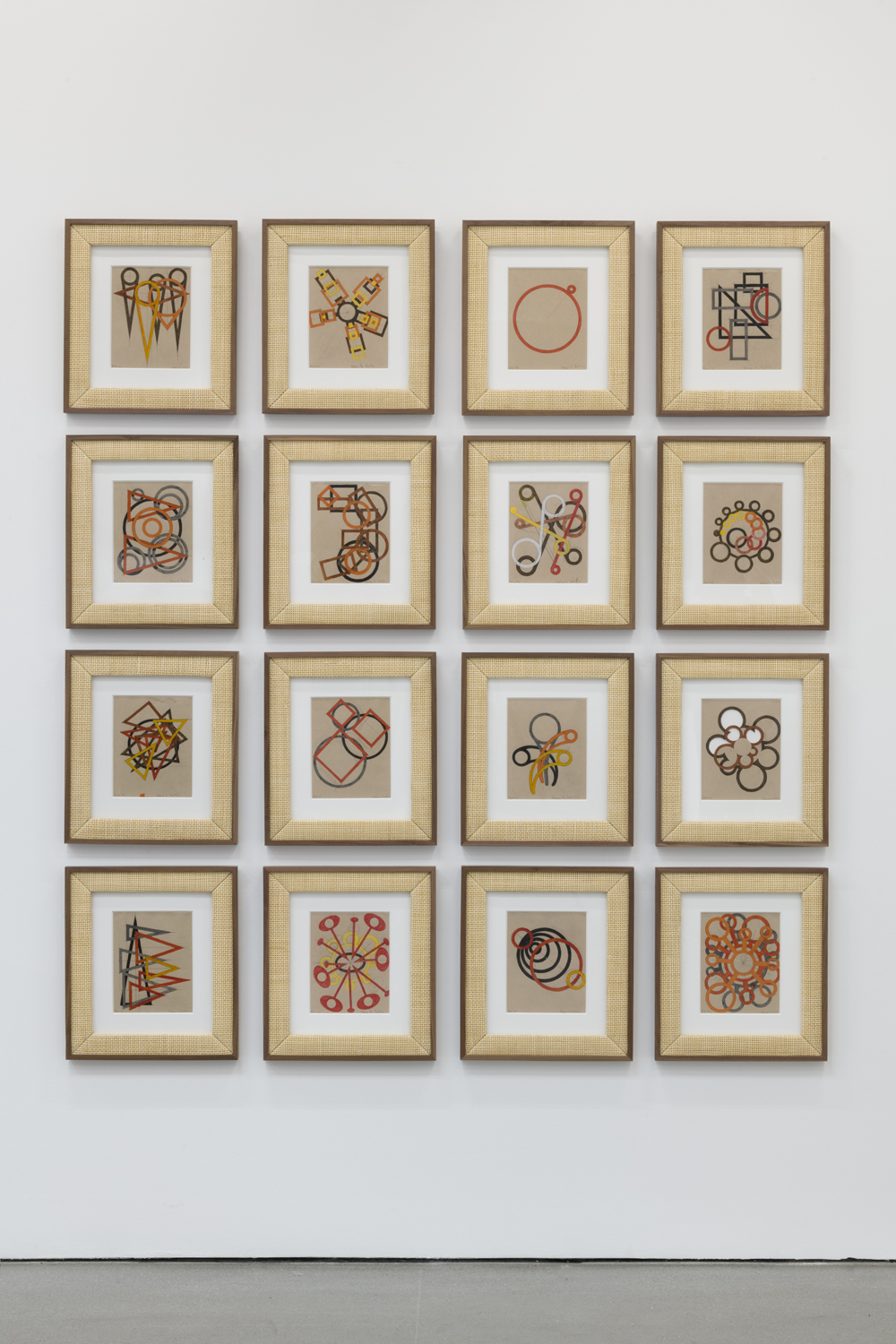

Marco A. Castillo’s The Decorator’s Home – his first solo exhibition in the United States after 26 years in Los Carpinteros collective – is a microcosm of the dichotomies and failures of modernism’s utopian ideals. Amid a raging Cold War that extended far beyond the US and the USSR, modernism infused a tinge of fascism disguised as national pride in the name of aesthetics, whether it be the folksy arts and crafts dreams of Frank Loyd Wright, or the concrete and rosewood pavilions of Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasilia. Cuban Modernism offered the same sense of freedom and hope in an embargoed state of isolationism and Marxist fervor. Needless to say, the movement didn’t last long – it sputtered out in the tropical miasma of communism’s last island holdouts. In A Decorator’s Home, Castillo captures this fervor: the dreams of space travel, the dreams of high-minded aesthetics, razor sharp lines, rich wood, and rare materials. All of this is imbued with the paranoia of a global race to the cosmos, and the coded languages of spies trading secrets while their Cuba Libre’s sweat into hotel coasters. In the back of the exhibition, a solemn and heartbreaking film, called Generation, is a symbolic six-minute epitaph for Cuban Modernism’s ambitions, it’s lonely siren songs of paradise, and youth crashed on the shores of their aspirations. In the end, Cuban Modernism’s shipwreck wasn’t due to lack of demand or desire. It was the sense of control that the architect’s of The Revolution – namely Fidel Castro and Che Guevara – needed in order to legitimize their violence and delusions of grandeur. As the movement died, many of the buildings were converted to hospitals, schools, and public works facilities. We got a chance to speak to Castillo about his exhibition, curated by Neville Wakefield, and about his own take on Cuban Modernism’s successes and failures.

OLIVER KUPPER: Where did the name for the show, The Decorator’s Home, come from?

MARCO CASTILLO: I had been doing research on Cuban Modernity, and there was this generation of designers at the beginning of the revolution that got involved in creating a new static for these people that were going to be the future of this country and the future of the world, because Cuba thought that they would convince the rest of the world to become communist. This needed to have an aesthetic.

KUPPER: It’s funny how revolutions need an aesthetic.

CASTILLO: This generation designed most of the objects we were supposed to use, like furniture, and also interior design for the spaces, for the workers, for the buses, for the hotels, and for the farmers. But at a certain point, the government stopped being interested in that.

KUPPER: Was it too ambitious?

CASTILLO: I think it was the mood of Fidel Castro. He got radicalized, he got very into Soviet politics, and he militarized the country. And so the static artists became an enemy because they were the creative people.

KUPPER: Yeah, a little utopian.

CASTILLO: Yes, too liberal. In the seventies, there was censorship for writers. The government destroyed the movement, the design, and the taste.

KUPPER: How many years was that?

CASTILLO: Twenty years, I would say. In Cuba you have Art Deco, Art Nouveau, but I’m fonder of this utopic moment. People were importing resources from the human past. For the colonial time, they were based on identity and they mixed it with the high-quality design from the northern country.

KUPPER: The northern influence is in your pieces, too.

CASTILLO: Yes, what I’m doing here is basically because this movement was interrupted. This stirred a frustration in all of us; we couldn’t have a complete aesthetic revolution. I behaved like an interior designer at the time, creating my own objects. They are not furniture, and they are not art. They are something in between.

KUPPER: Object-art.

CASTILLO: Yes, this creates a lot of influence in them. They look like decoration.

KUPPER: At times it reminds me of Brasília.

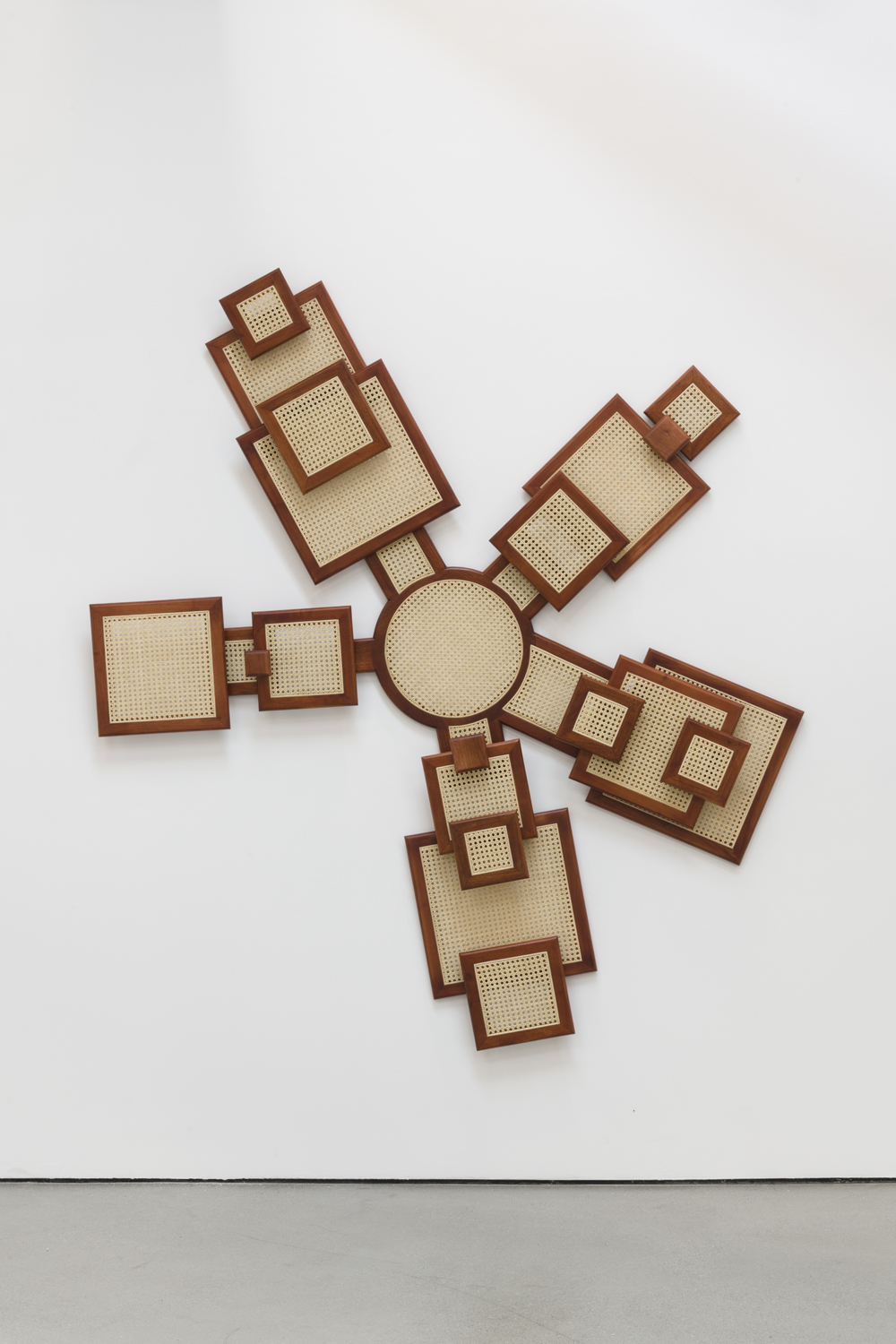

CASTILLO: Yes, except the Brazilians use rosewood, and we use mahogany. Cuba has the most beautiful mahogany. It’s darker than the rest. Also, we have a little bit of the Soviet influence over furniture—more practical. The Brazilians were more like peacocks, more exaggerated at times.

(walking over to another piece)

KUPPER: What’s that?

CASTILLO: This is the type of wood people use to make cabinets. It smells so good.

KUPPER: When did you start using caning?

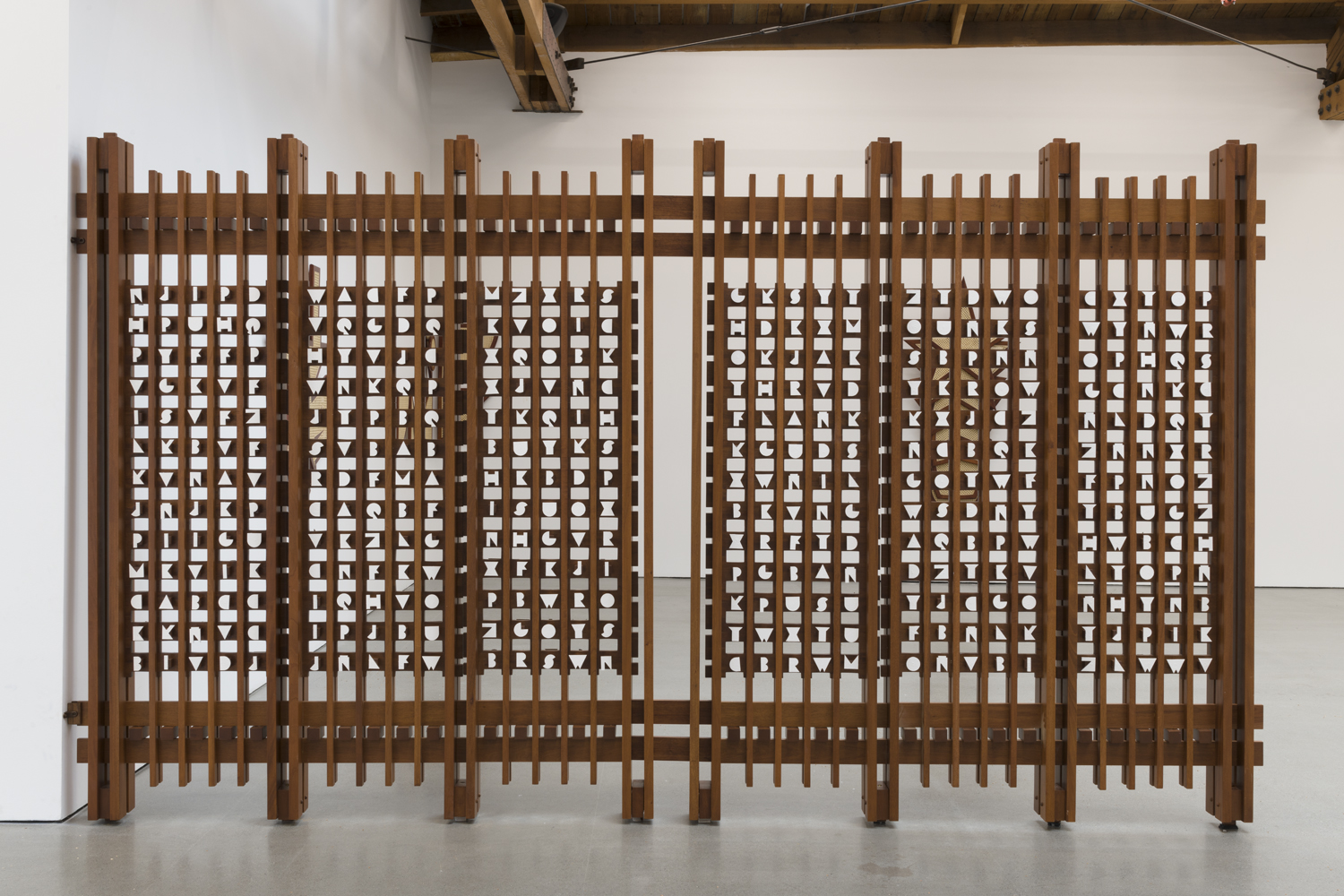

CASTILLO: It was after the Cuban movement. I realized they were using this old material to do things that were very modern. Also, they were doing a lot of screens. There was a very tropical feeling in every piece of furniture—very delicate—you couldn’t really read it immediately. For example, they use a combination of mahogany and white surfaces. It would remind you of a coconut. I did the same here (walks towards screen). I designed the outside of it. I made it white, so it looks a little bit like pieces of coconut. A screen in a very important place called Salon de Protocolo El Laguito, the Protocol Room of El Laguito, inspired this. There is a huge screen that reminds me of this one, but it doesn’t have the alphabet. I added an alphabet because it was sort of an addiction of the Cold War.

KUPPER: Coding…

CASTILLO: Yeah, people really wanted to know these codes; there was lots of paranoia. (laughs) What are they saying? It became almost like art.

KUPPER: Would you consider there to be a Brutalist element to any of these pieces as well?

CASTILLO: You know when you’re dealing with this socialist element, Brutalism is always there. This (pointing to a caning piece with stars) reminds me of our monuments. This is pure Brutalism.

KUPPER: This is very symbolic.

CASTILLO: It represents a little bit of the revolution. I come from a country that had a lot of fun—a beautiful, turbulent country. Cuba was very rich in the beginning, but not after the revolution. I represent that as a circle. Simple, beautiful, perfect. It turns into a star, which is a very complex, geometric figure. At the same time, it reminds me of the back or the bottom of a chair.

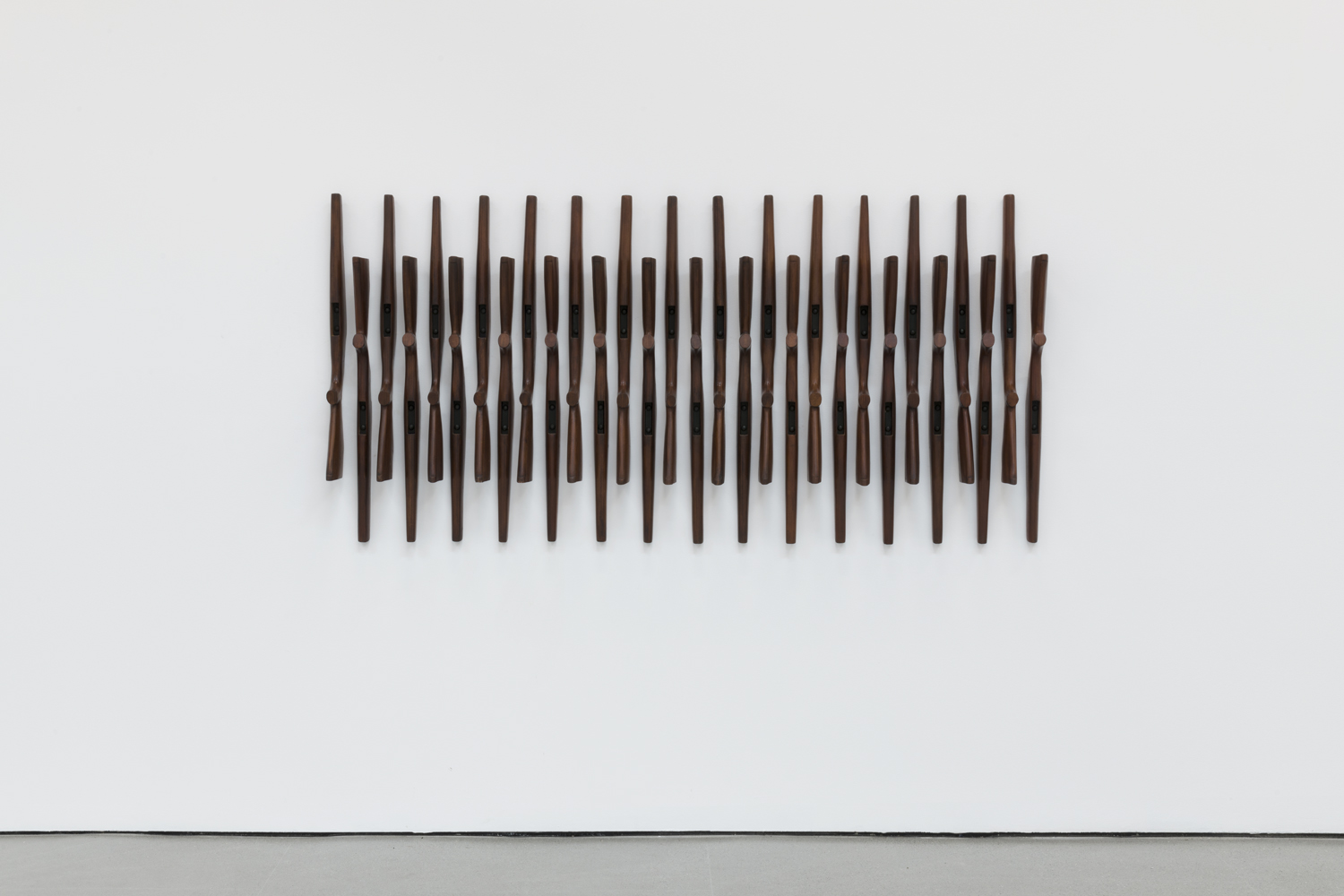

KUPPER: What about the rifles?

CASTILLO: The whole exhibition evolves from more abstract work to the more committed, symbolic, and engaged with the later alternative reality. It’s easy for me to imagine that an artist or a designer could have made a poster creating optical art with rifles as a monument, as a creative item. It never happened, and I never saw it, so I made it.

KUPPER: Was it a military aesthetic?

CASTILLO: There was a moment of militarization. I had to start learning shooting when I was thirteen, and I got these preparations every year until I was eighteen.

KUPPER: You weren’t going to join the army?

CASTILLO: No, it was not for me. (laughs) I don’t even like weapons. It just fascinated me—the shape of the rifle when you buy it creates a completely different object; it turns into something else. This is an American gun. I think it’s the Springfield.

KUPPER: It’s a pretty common rifle.

CASTILLO: My grandfather had it. It’s the rifle I always saw when I was a child. He was a hunter. You know what we hunt in Cuba? Guinea chicken.

KUPPER: What’s a Guinea chicken?

CASTILLO: It’s a beautiful animal.

KUPPER: Not like a Guinea pig?

CASTILLO: No (laughs), it’s a chicken, but it’s so beautiful. It’s a very strange animal. It looks like it’s from a patisserie.

KUPPER: Interesting.

KUPPER: (gesturing towards the sculptures across the room) These definitely remind me of the Cold War shapes—space-age shapes.

CASTILLO: Totally, because all these amazing designs started in that era.

KUPPER: It was the beginning of these explorations with satellites and this idea of our future in space.

CASTILLO: The future would be space, the future would be socialist, the future would be capitalist, which there was a big doubt about—there was a fight about it.

The Decorator’s Home is on view through July 13 at UTA Artist Space 403 Foothill Rd. Beverly Hills, CA 90210