interview by Lara Monro

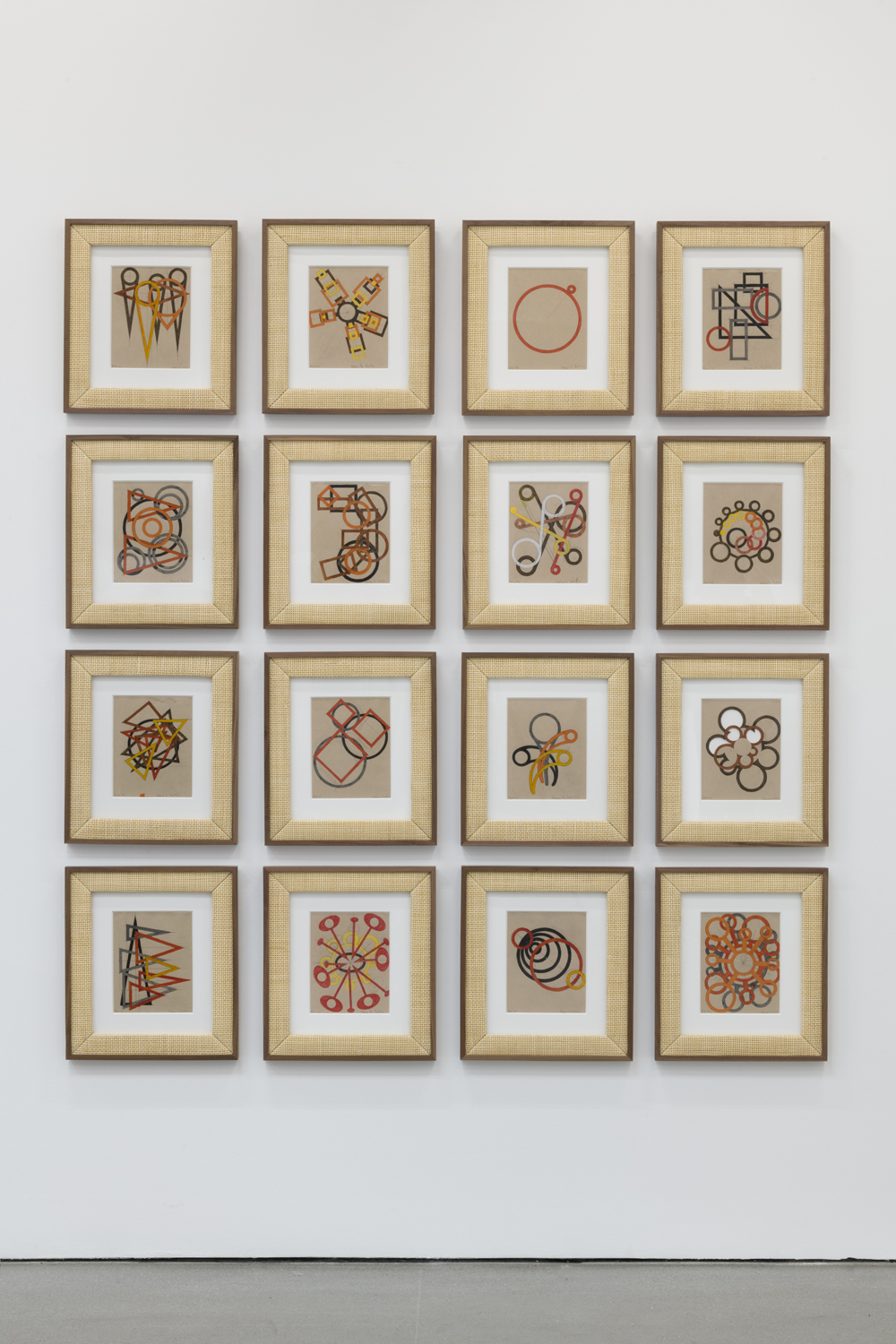

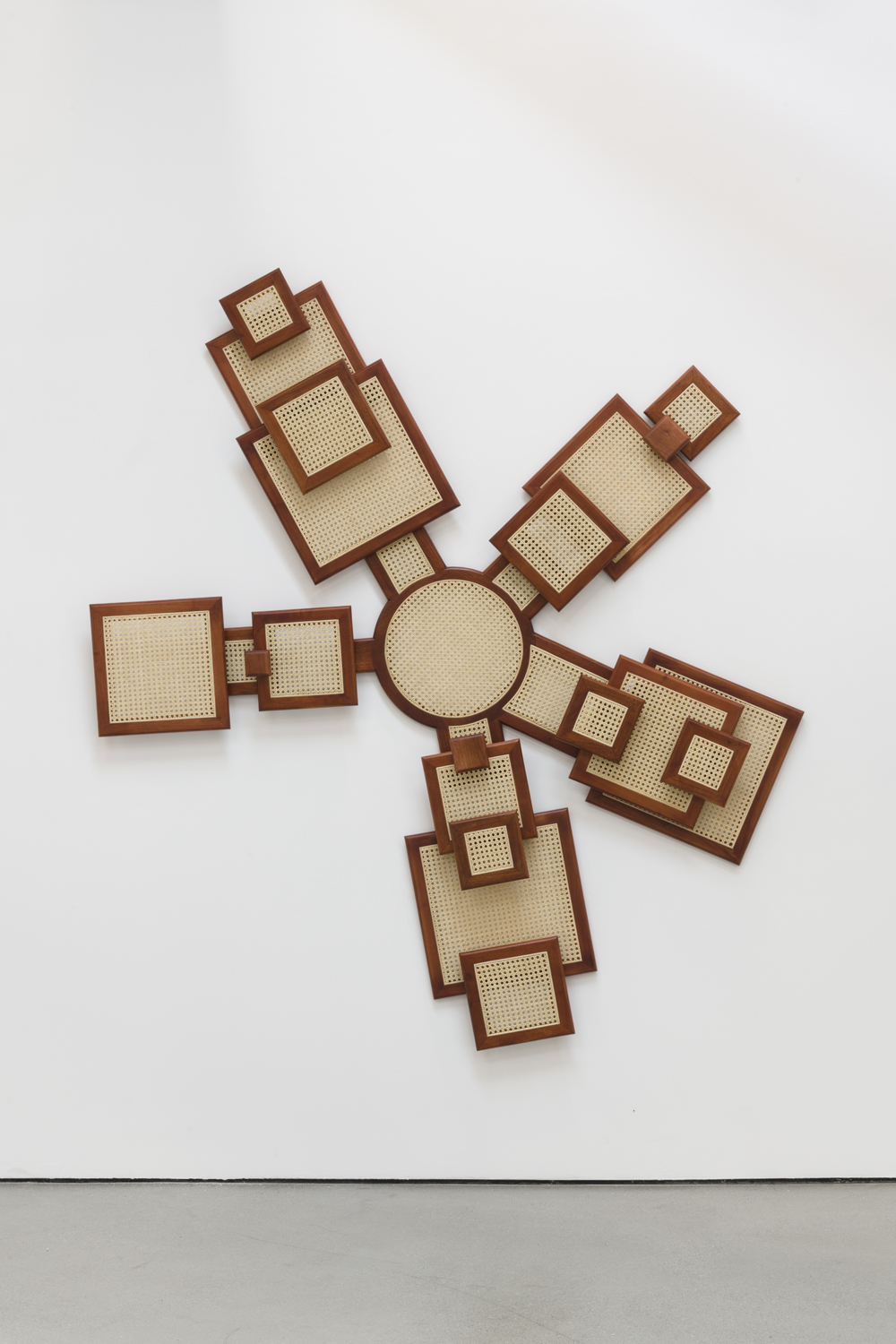

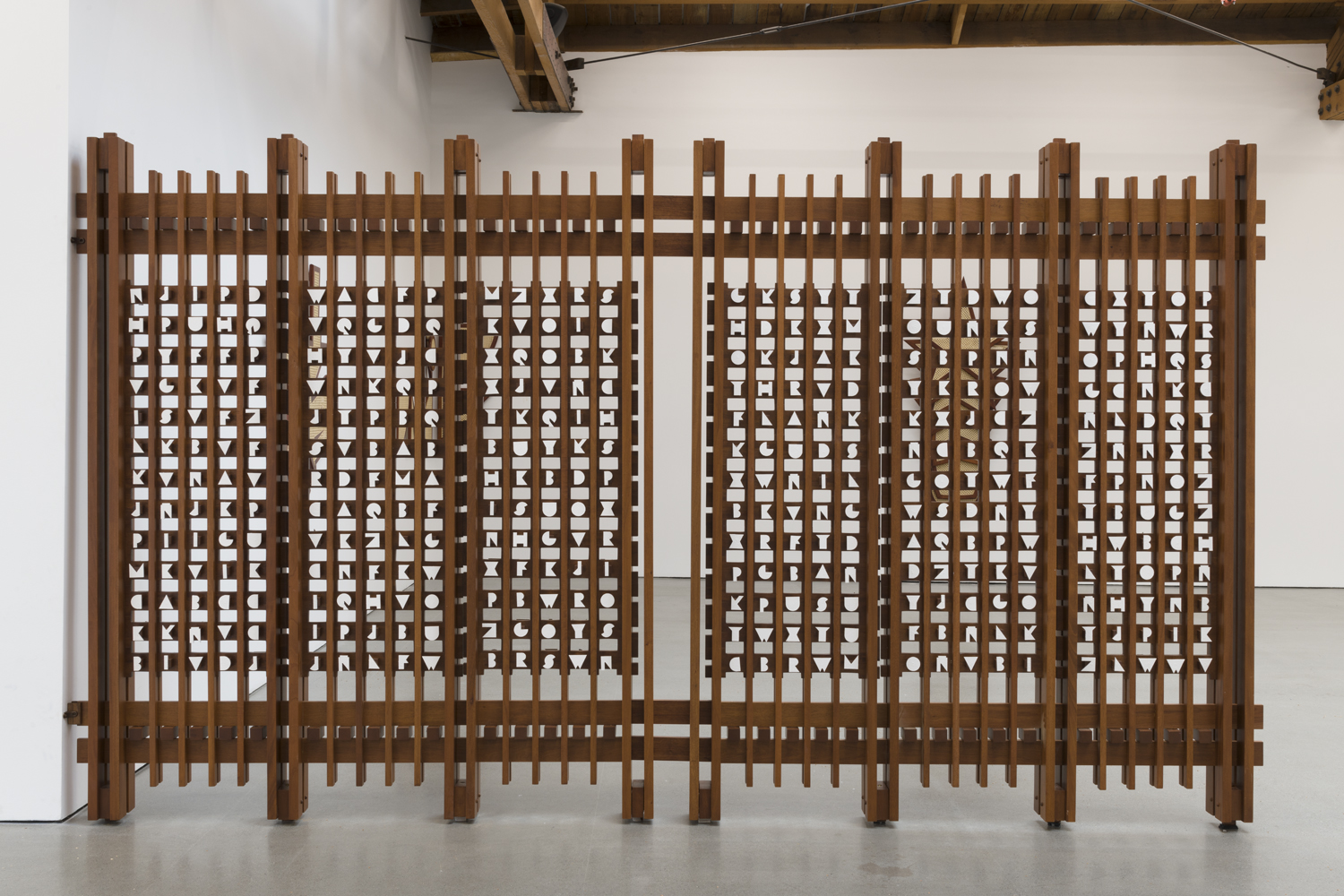

Navine Dossos uses painting to question the way in which we see, understand, and represent the world around us. In Panicle Paintings, she continues her line of artistic enquiry with fifteen works that examine the world’s changing relationship to the digital realm and documents the experience of becoming a parent during a global pandemic. Like so many, Dossos turned to an online community to stay connected as both an individual and an expectant mother. Each work acts as portraits of fifteen parents who, like Dossos, gave birth during the Covid-19 pandemic. These figures appear as palms and a multitude of other hybrid trees, deriving from Sumerian seal scrolls that symbolize childbirth and fertility. Dossos uses the ancient stories of gods such as Inanna/Ishtar to highlight, and also subvert, tropes of identity around motherhood. To accompany her metaphorical portraits of people as trees, Dossos includes familiar logos such as the WhatsApp, Twitter and Apple symbols. These are used to show the world’s intensified online existence, which resulted in new archetypal forms of visual language.

Autre’s London editor-at-large, Lara Monro, spoke with the artist about her personal connection to Sumerian seal scrolls, the societal expectations of a parent’s role, the importance of mythological representations in their portrayal of the masculine and feminine coexisting within a single entity, and how we can call upon this in generative and affirming ways.

LARA MONRO: Your work has often focused on finding a new language to reflect patterns and connections, which you then generate in the digital world. This series focuses on your need for online connection during the pandemic as you were navigating becoming a parent. Did it feel like a natural continuation of your artistic line of enquiry?

NAVINE DOSSOS: Yes, absolutely. So much of my work in the past few years has been about the lives we live online and how that connects to archetypal forms of visual language. For instance, how images such as the Twitter bird, the Wifi symbol, the WhatsApp speech bubble, and the Apple logo are all instantly recognizable to us and carry meaning. It wasn’t a big leap to take that language and apply it to the lives we all lived online whilst isolated during the Covid-19 pandemic. This period intensified the online lives of many of us and introduced new symbols to the lexicon that were specific to the health issues of the virus—how to stay safe and where to buy things online when we were unable to venture out.

MONRO: Can you tell me about your exploration into the ancient symbolism of palm trees in Sumerian cylinder seals and how you started to draw parallels with your experience in becoming a mother?

DOSSOS: I was approached by a good friend and collector of my work, Hooda Shawa, to make a work for her relating to the Sumerian ideas around the palm tree in particular. She had been looking into this for her own research and thought the subject matter might chime with me, given my past work on palm trees that culminated in a large-scale, site-specific installation at the Benaki Museum of Islamic Art in Athens called Imagine A Palm Tree in 2016. When it became clear that the Sumerians linked these trees to fertility and childbirth I felt a very personal connection to the subject given my recent experience of becoming a parent, but also how to explore ways to represent new parents without falling back on figurative tropes of pregnant bellies and breastfeeding babies. There is so much more to say about this radical shift in identity and that doesn’t necessarily have to be linked to a bodily portrayal. So, this gave me a way to explore what was possible through making metaphorical portraits of people as trees.

MONRO: It is interesting how you managed to marry nature and ancient traditions/history with 21st-century technology in such a harmonious way. What was your process for painting the series?

DOSSOS: I began by looking at existing images of Sumerian seal scrolls from various museum collections, and identified several types of representation of trees from within this very defined and highly symbolic existing visual language. I then worked on fifteen paintings simultaneously, drawing the trees to the same scale, and making sure all the backgrounds were part of a linear scroll-like continuation of bands of color. These colors are directly linked to those found in the Ishtar Gate, currently on display at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin (although it should be returned to Iraq in my opinion) and relate the paintings on paper to a more architectural heritage of temples and sacred space.

As the trees began to emerge on the paper, they also took on ‘personalities’ of parents I knew who had also given birth during covid, and I began to add technological symbols that related to these individuals and my relationships with them. For instance, if we often communicated by WhatsApp, I would add this logo, or if I knew they used Amazon a lot to get baby supplies, I would include this. In some cases, we had made plans to see each other that had been canceled due to travel restrictions, in which case I would make sure to put a ‘no fly’ image in there too. So, many of the contemporary symbols that appear are those that were pertinent to our shared experiences during this time.

MONRO: In addition to your exploration of the palm tree and its association with the feminine, you also include a variety of hybrid trees, which are known to have characteristics that are both male and female. Can you tell me more about these?

DOSSOS: At the goddess Inanna/Ishtar’s temple at Uruk and many other sites, sacred prostitutes of both genders were employed to ensure the fertility of the earth and the continued prosperity of the communities. Transgender individuals, known as kurgarra, castrated themselves, while those born female who identified as males were known as galatur; both were thought to have either been transformed by Inanna/Ishtar herself or created by the father god Enki to rescue Inanna from the underworld (as described in the epic poem “The Descent of Inanna”).

So much of parenthood becomes a reduction of a person to gender and biological function. I felt this very keenly not only when trying to conceive, but also in motherhood. After years of exploring myself and more gender-neutral/queer aspects of my identity and relationship with my partner, I felt much of this work was quickly undone by the societal expectations of the roles of parents. It took a long time and hard work to reconnect with these aspects of myself. Many of the parents I know have more complex gender identities and I wanted to be able to address this and not make the paintings as reductive as the experiences I had been through myself. Sumerian culture had the kurgarra and galatur as important figures in the sacred life of society. The seal scroll symbolism includes fictional trees that are a mixture of the palm and cedar, as well as the Tree of Life, which also contains both parts of the reproductive process. It isn’t about making all the trees gender-neutral or queering them per se, so much as pointing out that even in such ancient history and its mythological representations, there are many ways in which the male and female coexist within a single entity, and that we can call upon this in generative and affirming ways.

MONRO: You mention Inanna/Ishtar, the rural goddess of agriculture; a unique and rare-to-come-by female figure in ancient history for being represented as an independent woman who does as she pleases. Can you tell me more about how she relates to the series?

DOSSOS: Inanna/Ishtar is a fascinating goddess to me. She represents fertility, love, desire, and also war. She holds within her the capacity for creation and destruction. The way she is written about in the epic poems is as a young woman who very much takes what and who she wants, and often gets bored with lovers and throws them over for new ones. She tends to get herself into some terrible situations—mostly through her own doing—and often because of her capricious, short temper, and her thirst for revenge when slighted. To me, she is quite relatable in her flaws and failings, and encapsulates what I so admire in the approach that Sumerian mythology has to its deities. The Ishtar Gate is also an iconic monument in Europe (again, it shouldn’t be there) and for years I have been inspired by its colors and designs. To bring together this monumental scale of the Gate with the miniature language of the seal scrolls, whilst keeping Inanna/Ishtar very much at the centre of things was an exciting challenge for me. My aim was to find a human scale in the middle of these modalities.

MONRO: How has creating this series supported you on your journey into motherhood and understanding how to navigate it?

DOSSOS: I started out by making three paintings for my friend Hooda, and this was the first studio work I had done since becoming a parent. It seemed a safe way to begin this life again once my child was old enough to go to nursery and I had some hours each morning to myself. But as the subject matter expanded before me, so did the series, and it grew incrementally each week until I was working on fifteen paintings simultaneously! Even this ability to start small and expand was an important step—insomuch as it was a gentle confidence-building exercise, rather than being thrown in at the deep end on a project with high expectations that might have been harder to manage emotionally and temporally.

I had never intended to show the full series, rather just to have them for myself as a means to an end of getting back into work. But I was lucky enough to have an informal studio visit with Alix Janta who runs Alkinois Project Space in Athens, and she encouraged me to show them with her as part of her program. The Panicle Paintings exhibition developed out of this, and finally included elements of wall painting in the installation. I felt very supported by Alix to make the show, and it was a way to have all of my friends—these parents in the paintings—present with me, urging me to get back to work, and to take pleasure in my work once again.

Panicle Paintings is on view through November 25 @ Alkinois Project Space 6, Alkinois Str., 11852 Athens