Joris Van de Moortel, 31, has intrusive bluish-gray eyes. They are unsettling; despite the subdued kindness that surrounds them. Looking in to them one realizes Moortel doesn’t see the same boundaries most of us do, the boundaries that most of us construct our lives around.

Moortel smashes, sometimes literally, the line between art and music. He is both musician and artist and the two feed off one another. Moortel makes mixed media pieces that often incorporate elements of his musical performances; a guitar he smashed on stage the night before, panels from a stage he played on. Sometimes the work comes after a performance; sometimes it’s made during.

The Belgian artist wriggled his way in to art school at 12 years old when he started following a friend’s father to night classes. Moortel graduated from the Higher Institute of Fine Art in Ghent Belgium in 2009. In his early 20’s Moortel sold his first piece through a gallery in Belgium. From that point on he devoted himself entirely to his work. Most everything in Moortel’s world is about simultaneity. At the same time that he was a child drawing nudes he taught himself to play the harmonica, guitar, bass and keys. At the same time that he began selling artwork he was performing in solo shows and with a variety of bands throughout Europe. At the same time that he became an artist he became a rocker.

Moortel stole the spotlight of the European art scene in 2012 when he had his first solo show at the Le Transpalette art center in Bourges, France. In 2014 he performed in an exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris titled “Don’t Know You’re Gonna Mess Up the Carpet,’ in which he stood atop a tube with a drummer inside and conducted a mind-bending rock performance involving video screens and neon lights. Moortel had his ‘coming out’ in the American art world this December at Art Basel Miami where he had his first solo exhibition in the US through the Denis Gardarin Gallery. Days before he had an exhibition open at the Contemporary Art Center of Wargem in Belgium. Next he is off to Madrid for a solo show at the Galerie Nathalie Obadia. In May he’ll come to New York for Frieze art fair. In between he sneaks back to Antwerp to spend time with his young children and maybe get around to cleaning his studio.

SCOUTMACEACHRON: Tell me about your Art Basel exhibition?

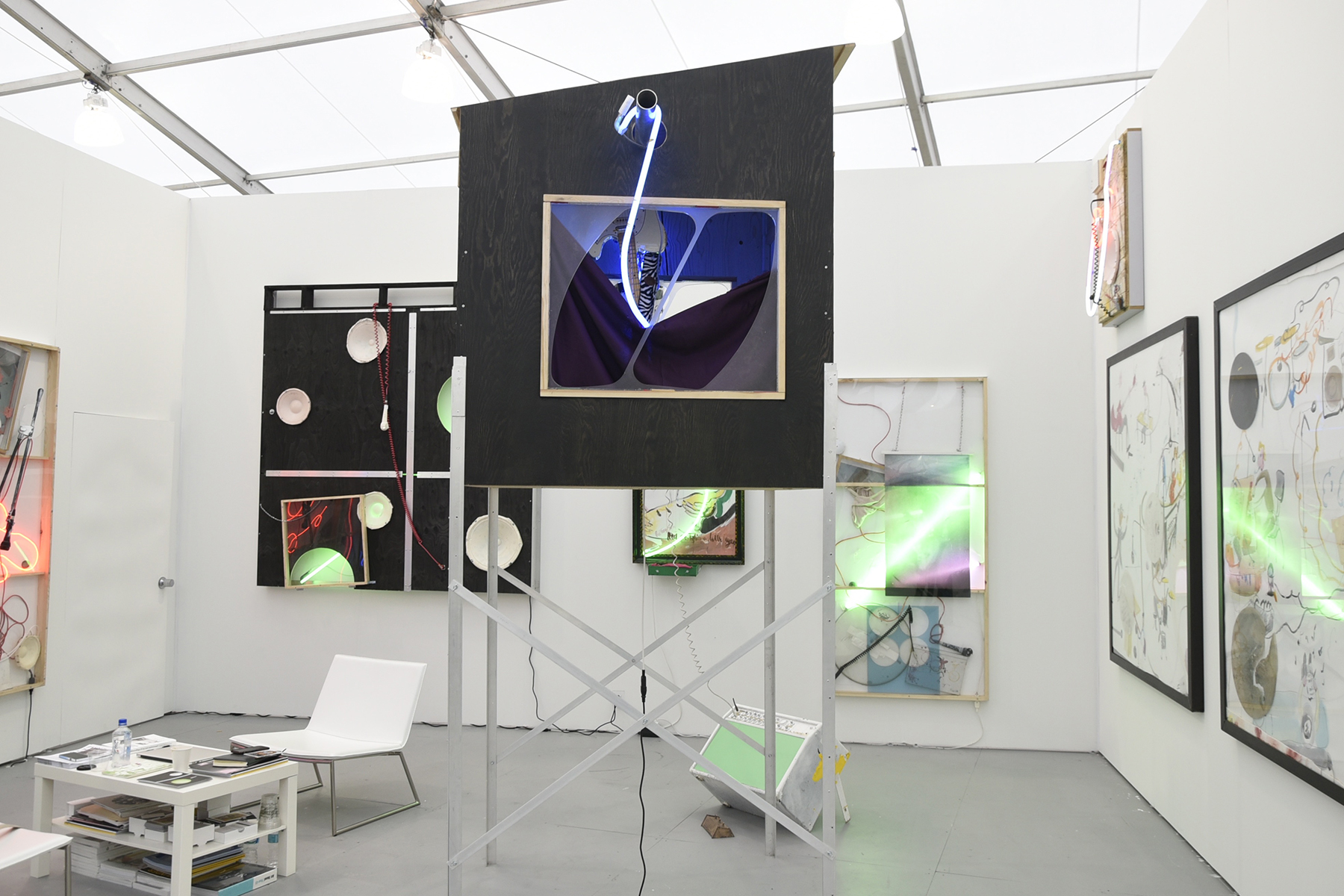

JORIS VAN DE MOORTEL: During the making of this exhibition I was also working on a big museum solo show in Belgium which opened the day before I left for Miami. There’s a lot of overlap between those two exhibitions. Like the installation here [gestures to house-like structure]; the one in Belgium is the size of this area [gestures to entire exhibition space]. It’s huge. The drawings in this exhibition are related to the one in Belgium; one is related to a CD recording I did and the other is related to a solo vinyl I did.

MACEACHRON: When you say related to, what do you mean by that?

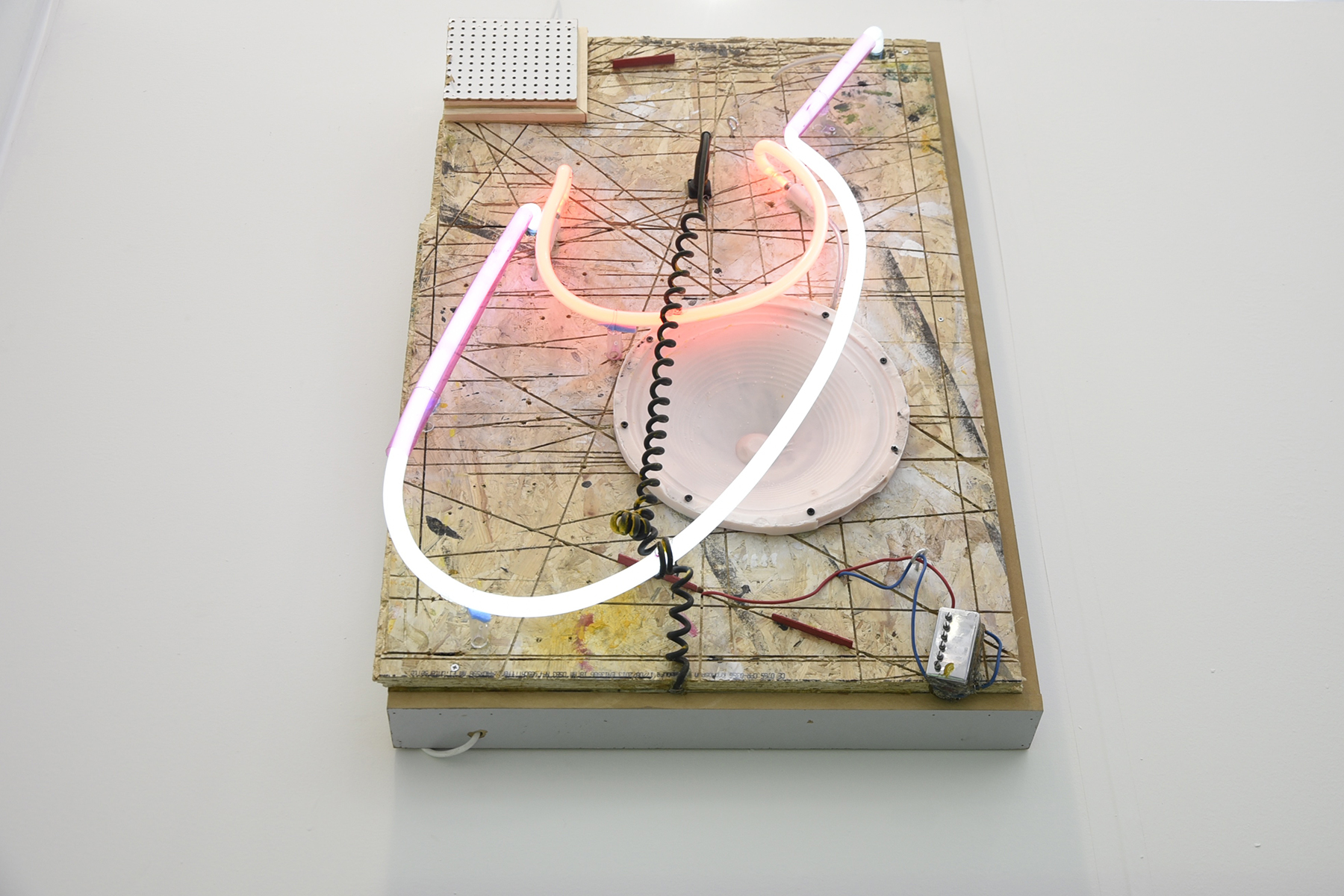

MOORTEL: This part of the work is part of the exhibition in Belgium but it’s much bigger with real actual speakers that work. These [Gestures to artwork] are casted speakers in resin. All the works here are muted. Nothing makes any sound anymore. These pieces, the back of this piece [Gestures to artwork] also contains speakers but it’s muted. Most of my pieces come from performances. Like this one is part of a stage from a performance I did in Belgium, Singapore and Paris. It is just one part of twelve panels that made up the whole stage. I sprayed it white with an air press gun. And the last one I did was a collaboration with the designers A.F. Vandevorst for a fashion show in Paris. This piece contains elements of the performance; part of the coat I was wearing, speakers, the effects I’m using, neon which is running through the piece.

MACEACHRON: When and why did you start incorporating these objects that are a part of your life, a part of your performances, in to your work?

MOORTEL: I don’t think about it in that kind of sense. I mean it’s all part of the studio. My studio is on the one hand a music studio but sometimes it’s more. At times I’m busy with music and then it shifts. All my wood, all my materials are there; the welding machines, the steel, the aluminum, the cast materials. It’s all in one studio. The performances play a part also, it really depends. Sometimes [the performances] come first and the sculptures come after. Sometimes it’s a part of it from the beginning. Sometimes the work is made during the performance.

MACEACHRON: Tell me about your musical background?

MOORTEL: It goes from age ten or twelve. That was the first time I really hit music, not only listening to it but that was the moment it really becomes important. Then of course I immediately wanted to play it myself but I never wanted to or didn’t take the time or wasn’t patient enough to take classes. Friends of mine did. I started out with the mouth harp and guitar, bass guitar.

MACEACHRON : Did you teach yourself?

MOORTEL: Yeah and friends taught me things. It took quite a few years. Now I play in quite a few bands. For me it’s hard to say something like or hear, “oh you’re a good guitar player, you’re a good bass player.” I would never consider myself like that because I’m not an academic, I didn’t study it. I collaborate with a lot of other musicians. Now I play guitar, sometimes the keys and sometimes also bass guitar in one specific band.

MACEACHRON: Do you remember what music you listened to when you were ten or twelve years old?

MOORTEL: The Doors.

MACEACHRON: Any particular album?

MOORTEL: All of them on vinyl, all of them on CD. I had t-shirts. I had a vest with Jim Morrison on the back. Had I been allowed to get a tattoo at age of fourteen in Belgium I would have had Jim Morrison on my back. I was completely, completely in to that. Also a lot of sixties and seventies music from San Francisco and LA. Then Velvet Underground, the New York scene. Patti Smith, Ramones. All very sixties and seventies.

MACEACHRON: Wow, advanced for a ten-year-old.

MOORTEL: [Laughs] Yeah, I know.

MACEACHRON: Did you go to art school?

MOORTEL: Yeah, when I think about it that’s why I didn’t want to study music. I started when I was twelve. A friend of mine, her father was going to an art school during the evenings and weekends. He was studying sculpture and had a sculpture studio. I asked, “please, could I join you, could you teach me?” It wasn’t really allowed until you’re eighteen but I said, “I really want to.” So I started drawing nude models for years. It was a lot of clay and plaster. I started welding at that age. I kept doing that until I was fifteen and then I went to an art school. I kept going to the other school as well. So that was my only occupation, drawing a lot of nude models, clay studies and painting.

MACEACHRON: So you weren’t studying normal school subjects at all?

MOORTEL: In Belgium you can go to an art school from when you’re fourteen. You get regular classes like math and language and everything but reduced in a way. Your focus is on art. Then I kept on going to art school for high school. When I went to University it was also art school.

MACEACHRON: The type of work you make now, how did that evolve from drawing nudes?

MOORTEL: Well you have all those study years. The way of working is only a growing thing. When you grow up as a human being it’s the same kind of thing I think. A major shift was around twenty, twenty-two when I started building installations. The first exhibitions were mainly installations, not really focused on sculptures or wall pieces or paintings. And then this took over again, by making sculptures again in to what I’m doing now. But it depends on museum shows and institutions. It’s all part of the same thing but you show a different chapter of something.

MACEACHRON: What’s your process like when you’re creating? What’s your studio like?

MOORTEL: Messy.

MACEACHRON: [Laughs] Do you sit around and think about things or do they just come to you? [Joris walks away and returns with glasses of water for us both.] Do you know something is going to be in your work when you see it?

MOORTEL: Like certain elements or parts?

MACEACHRON : Yeah, how do you get from nothing to that [point to one of his artworks]?

MOORTEL: Most of the, for example the basis of this kind of piece they come from really big installations. So the frame is already there some how. Like this frame was apart of the stage. So the frame is there. And it wasn’t the intent, I mean those frames I didn’t use them for two years after the performance. Also with these [gestures to artwork] they traveled from my show in the Netherlands in a museum then to Berlin then to Paris and then back to studio. I almost wanted to throw them away but I kept them for some reason and then they were the first pieces for a gallery show I was working on at Galerie Nathalie Obadia in Brussels. They got really well received. From one thing comes another. A lot of pieces travel from show to show and don’t get sold and then eventually they end up in another piece. Mostly the moment it gets sold that’s where it leaves me so I can’t redo it or whatever. When pieces come back to the studio they don’t leave out the same way.

MACEACHRON: So everything is constantly evolving, including yourself, I suppose that’s the nature of art. Did you go through a starving artist phase or were you successful from a young age?

MOORTEL: I always had jobs and worked. I was self-employed quite often.

MACEACHRON: What kinds of jobs?

MOORTEL: Record stores, bars. That was only when I was in art school because I didn’t finish it. I did two residencies but I didn’t finish with any degree. At twenty or twenty-four I started working with my first gallery in Belgium. It worked out from the first moment. I did one really huge piece for the gallery show and it was sold. I could make a living off that for almost two years. So then I became self-employed.

MACEACHRON: It sounds like most of your work is much larger than what’s here at Basel.

MOORTEL: Yeah, there’s always a balance with these kinds of things. But this presentation is what the gallery shows look like.

MACEACHRON: Speaking of galleries, how did you connect with the Denis Gardarin gallery?

MOORTEL: It is the first time we’ve worked together but it’s been going very well. They’re really working hard. We’re almost sold out so it’s moving. Also in terms of audience they’re all American collectors. They didn’t know me before so they’re responsive and very… I’m really surprised in a way. I came here thinking, “oh this will go fine.” I wasn’t worried but I also didn’t expect anything. But American collectors are like, ‘oh this is great, I’ll get it.’ That doesn’t happen in Europe. People come back. Even collectors who have five pieces say ‘oh let me think about it, can you put it on hold for a week?’ This doesn’t happen in Europe.

MACEACHRON: Americans just go for it. So you’ve sold some pieces so far, everything?

MOORTEL: Basically everything yeah. I mean there are a few left but most have sold.

MACEACHRON: This is your first solo show in the US right?

MOORTEL: Yeah, I was in the Armory show before but that was five years ago so the work was kinda different. Something like this it’s the first time.

MACEACHRON: This is an incredibly vague question so answer however you like. What differences do you see in the art world in Belgium/Europe and the states?

MOORTEL: I think with all these fairs… it’s the same as shopping for clothes for instance. Ten years ago you didn’t have the shops in Belgium that you had in New York. But now you have H&M, whatever, Zara, that took away the exotic kind of thing. The art fairs took away some of the exotic things. You don’t have to discover in Europe European artists. You’ll have to go to Brussels, Antwerp to discover… well we’re talking about me, to discover me because I’m in a European art fair or gallery. So in a way that generalized and made it easier to go around, which in a way is a good thing because there’s so much going on. You need those art fairs to actually see something because you can’t go all over the world all of the time. A lot of things have changed through the years. The world population has multiplied by three or four. So also the art world is growing. In the sixties and seventies it was way different, there were less artists because there were less people on the planet.

MACEACHRON: This is another vague question but what inspires you? Other artists? A feeling?

MOORTEL: It depends. It’s come from so many different angles. It’s music, the work itself—looking back at pieces you did years ago or even last year—things you read. I’m always reading multiple things at the same time. I’ve been absorbed by Albert Camus again, his essays on Kafka. George Bataille, his essay “Rotten Sun” is the title of the exhibition. It comes from many different angles. I don’t have a specific sort of… there’s a certain pattern or a wave of making things and then there are times that I go to the studio but don’t do much. I read, I play some music. And then there are times when you don’t have time to because you’re really making work. It’s always in that kind of wave. In times, for me it works to go to the same places over and over. Like next week I will hang out in one coffee bar where I get in to that rhythm of reading, writing, reading, writing, reading, writing. I don’t have time for that when I’m working in the studio. Then the next project is in Madrid so I have to work on that again. It will go in a wave of thinking about what I have to do then doing it.

MACEACHRON: What’s your process like in a physical sense? Are you regimented, do you get up very early, do you stay up all night, do you drink bourbon?

MOORTEL: I have two kids. I’m not really a… I used to drink a lot but I don’t like alcohol anymore.

MACEACHRON: Do you think it changed you at all as an artist?

MOORTEL: Um, you’re dealing differently with time. The concept of time is completely vague when you don’t have kids, when you don’t have a job because as an artist you don’t have a real job. You don’t have limits on time; you don’t have to wake up, you don’t have to go to sleep, you don’t have to do anything you just have to… you have you’re deadlines but it’s really vague. Of course you work a lot but it’s not, you don’t need an alarm clock or anything. With kids you also don’t need an alarm clock because they wake you. It makes you go to bed earlier, it makes you drink a lot more coffee, it makes you drink less alcohol, it makes you go out less—so all the good stuff.

MACEACHRON: What do your children think of their dad being an artist? I know they’re young.

MOORTEL: When I Skype with them they’re more interested in the food I’m getting here than what I’m actually doing out here. But no they really enjoy it when they come in the studio, it’s opposite the house. The six year-old likes to draw, she likes guitar and noisy stuff. Last time she was in the studio she said, “Daddy, there’s so much stuff out here I really need to help you to get some order in here. I really should help you make your stuff.”

MACEACHRON ; My goodness that’s pretty cute.

MOORTEL: Yeah it was really sweet. It was really honest. Like, “there’s so much stuff out here.”

MACEACHRON: That is sweet. Are there any installations or pieces that mean more to you than others, perhaps a defining moment in the process?

MOORTEL: In a way a piece like this comes from a specific installation, which really means a lot to me. The piece is like a proper extraction from that so it’s a direct storyline for a piece like this. There are many more angles and stories for a piece like this. When you start talking about it it’s like “this comes from there and this comes form there.” But I always work within the concept of an exhibition, like a solo show, even if it’s only a fair booth. They’re all connected somehow to each other. Ideally, when you talk in terms of collection they should get this and install it like this but I’m not thinking like that because it should be how it was conceived and how it’s made in a way.

MACEACHRON: You mean all the works here should be displayed together?

MOORTEL: Yeah, but it’s also a nice idea that everything goes. They come from a different angle, different sources, they come together at one point and then they leave each other. That’s also beautiful.

MACEACHRON: Where are you going next?

MOORTEL: Hoboken, it’s a part of Antwerp. Next up is Madrid. Then New York in May for Frieze. Then Paris, Vienna, Belgium.

MACEACHRON : How long do you get to be home and see your family?

MOORTEL: Oh as much as I can.

You can catch Joris Van de Moortel's solo exhibition "Ça vous intéresse l'architecture? Botanics of sound in which wires get crossed and play with the rythmic structure" on view now until January 31, 2016 at BE-PART in Waregem, Belgium. text, interview and photographs by Scout MacEachron. Follow Autre on Instagram: @AUTREMAGAZINE