interview by Jason Schwartzman

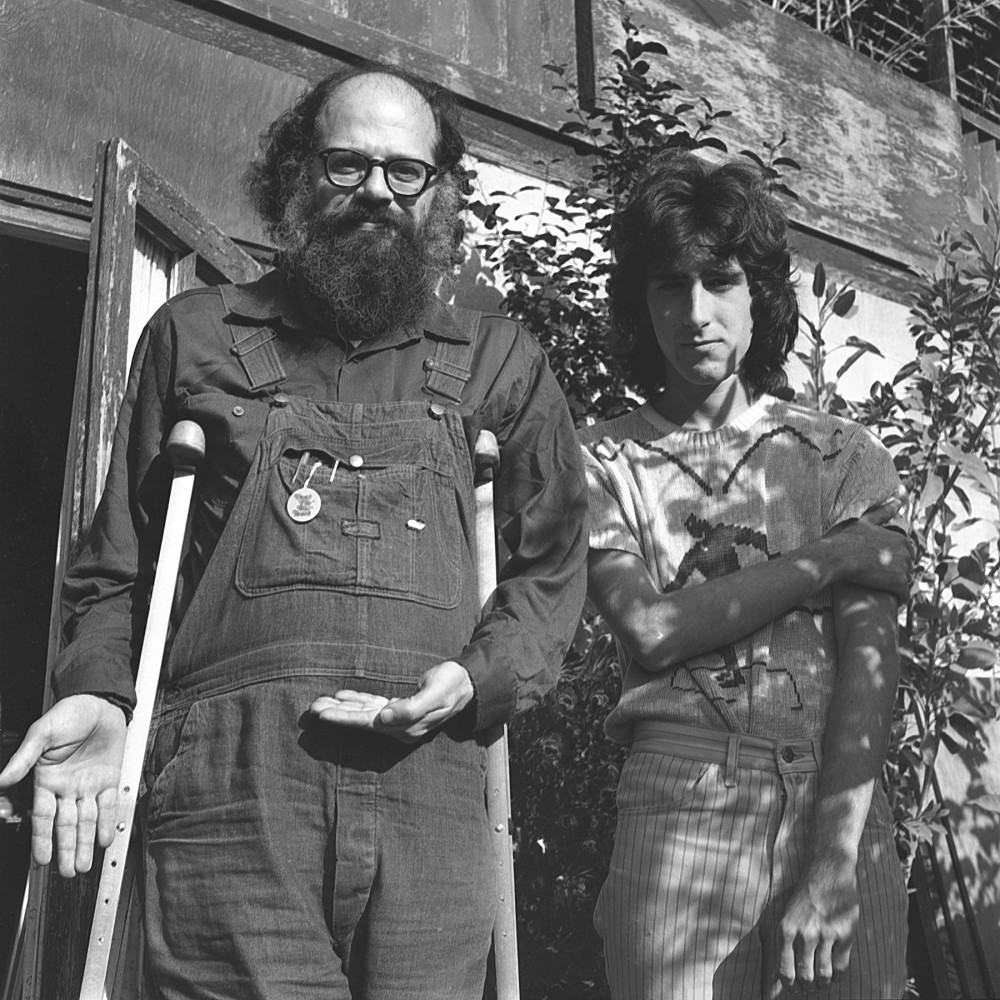

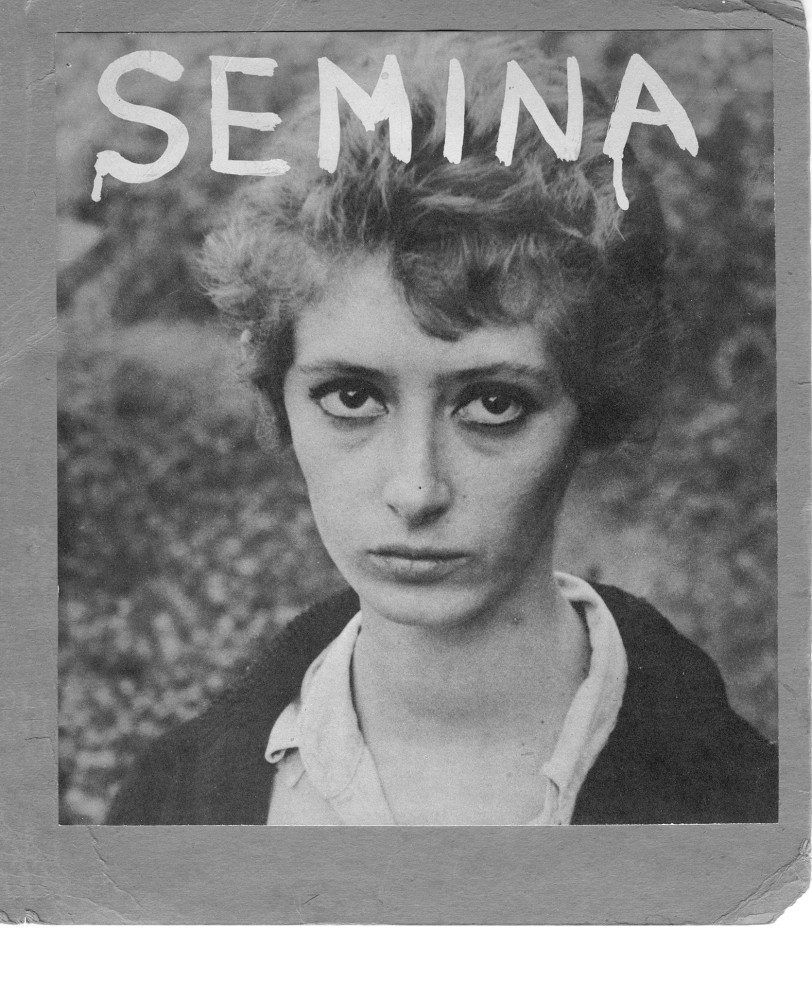

Wallace Berman carves a mysterious, counter-cultural figure in the cave wall of Los Angeles folklore. His legend is enhanced by a tragically early death on his fiftieth birthday as a result of an automobile crash with a drunk driver in Topanga Canyon, further cementing his myth as the beatnik of the Southern California chaparrals. There was only one public exhibition of his artwork, at the legendary Ferus Gallery. After the opening, the vice squad got a tip about explicit material in the show. He was arrested and later convicted for showing lewd and obscene works. There is an outsider quality to his jazz and bebop inspired assemblage work and a Zelig-like quality to his persona, popping up in unlikely places, like a scene in Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider or the cover of The Beatles Lonely Hearts Club Band. In a new memoir, entitled Tosh, Berman’s son opens the opaque curtain on the enigmatic artist through a bildungsroman of the Beat Generation and hippie counterculture, a childhood on the frontlines of 1960s Los Angeles and San Francisco freakdom. Tosh Berman and Jason Schwartzman got together for a public conversation at Skylight Books to discuss his memoir and growing up in Wallace Berman’s world.

JASON SCHWARTZMAN: I’m gonna just start with a very simple question, but I am curious, why now did you decide to write a memoir?

TOSH BERMAN: Well, first, it took me ten years to write this book, Tosh, and, I wrote it because a gentleman by the name of Terry Lauren, from Detroit, was editing a special art journal online at the time. Terry Lauren was part of the group, or art collective, called Destroy All Monsters with Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw. He was the other power trio person. He came up to me to ask if I would write something about my father. At the time, it was sort of totally unthinkable that I would even consider writing anything about my life or my family.

SCHWARTZMAN: Why?

Tosh Berman: Because I was sort of taught by my father not to write about the family, really, in a certain aspect. And it wasn’t like a law type of thing but just something that was not encouraged to share with, um…with you. So, when you leave, don’t tell anybody.

SCHWARTZMAN: The memories and the stories in the book, were they all there (snaps fingers) in your head? You’d just been waiting to write them? Or was it a process?

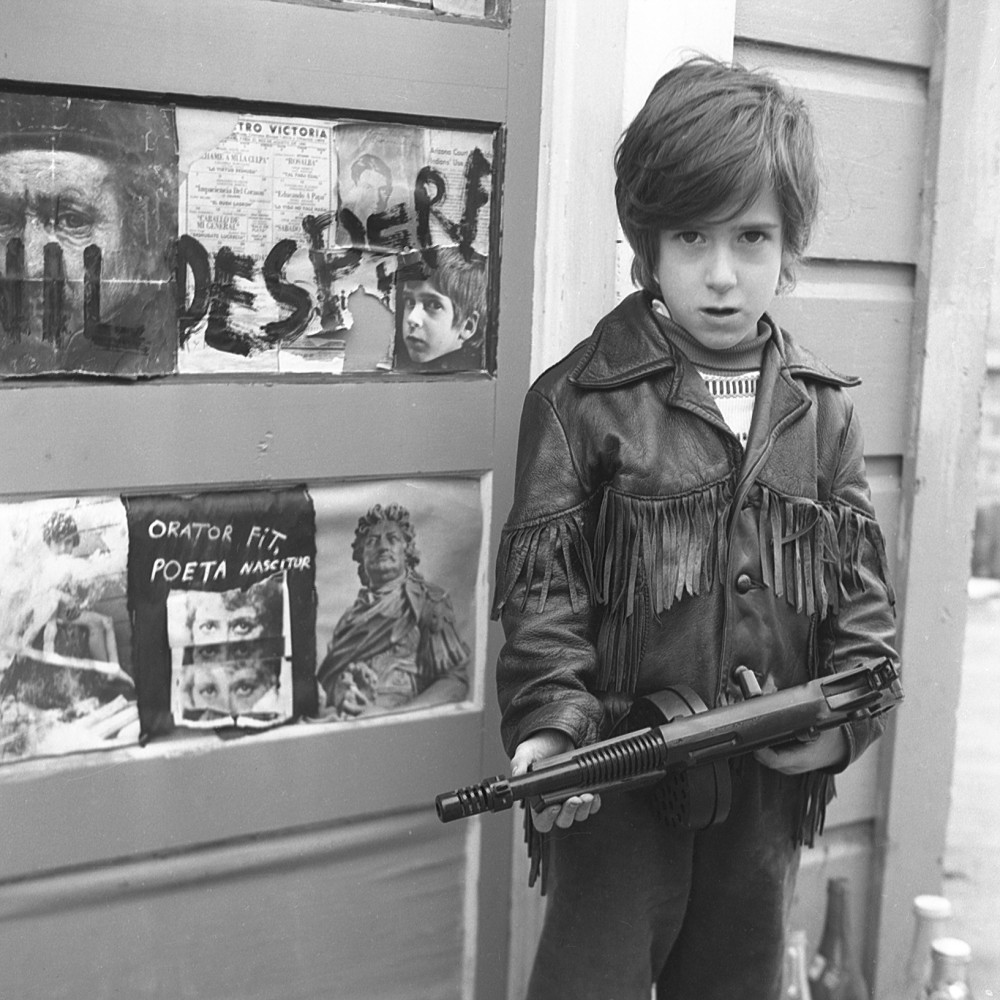

BERMAN: I believe so. I mean, in a sense, my childhood is the most vivid part of my life, so far. It stands out more than anything else in my adulthood, for instance. Though, definitely, as an adult, I find great importance in enjoyment and etcetera, etcetera. But definitely, my childhood had such a vivid stamp on my memory—on who I am—that I still, to this day, feel like a child. I’m very fortunate to have been photographed by my father at a certain age, from a certain time, so when people see me, they think of me at that age. I think the identity of Tosh is very much me as a teenager or as a child.

SCHWARTZMAN: In the book, you're taken out and you're just a part of your parents’ lives in a way that I think is great. But did you feel like a child when you were a child?

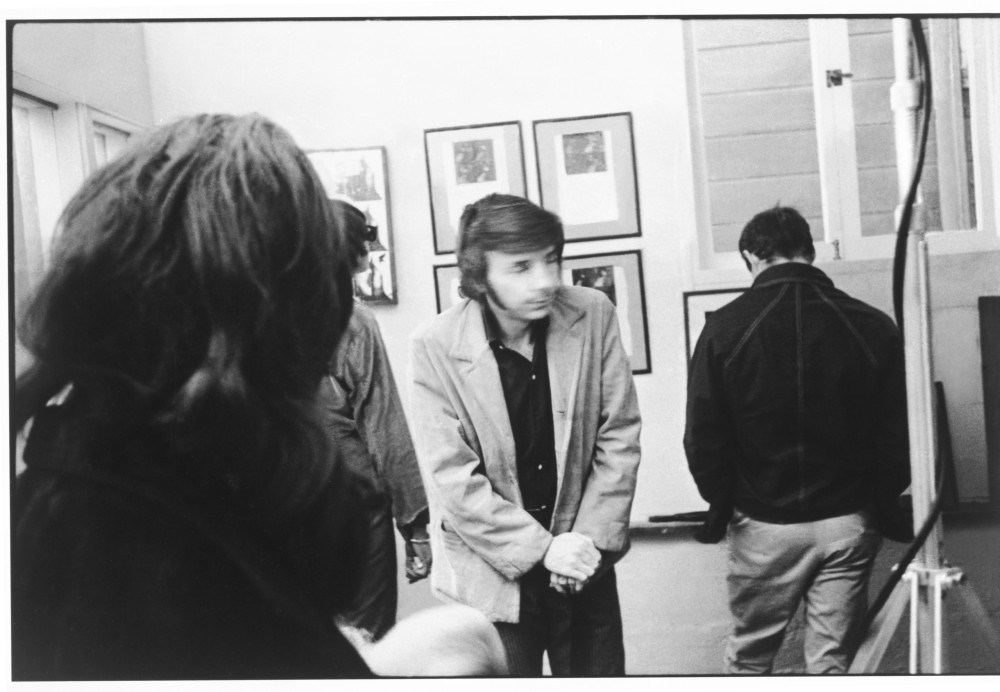

BERMAN: Yes. For instance, I would be taken to an event and I would sit on my mom’s lap. I have very little memory of going to childhood events, or children’s parties. All my thoughts are exclusively about going to gallery openings, or going to, you know, Marcel Duchamp’s opening at the Pasadena Museum.

SCHWARTZMAN: I am just so curious about what you were aware of at the time. You know, like you met Marcel Duchamp.

BERMAN: This is my relationship to Marcel Duchamp. I went to his opening and everybody was dressed really nicely. It was kind of a formal affair. When Duchamp, or Marcel, was in a room, his presence was so strong that all the people in that room had their focus on the presence of Marcel Duchamp. At the time, he was still like an underground, cultish figure. But, Marcel Duchamp was such an incredible presence for other artists at the time, not for the general audience, you know.

SCHWARTZMAN: Yeah.

BERMAN: But, to me, I knew he was French. And that made a big impression on me because he was a foreigner. I also knew he was an artist, and he made a sculpture with a bicycle wheel. As a child, the bicycle wheel was so common for any child. I mean, I didn’t ride a bike at all, but I knew people had bicycles, and I’d seen bicycles in comic strips and books, you know. So, seeing the bicycle wheel on the stool meant a lot to me because I totally understood the piece. It’s a bicycle wheel! I didn’t think about it as, “Is this art? Not art?” or an ironic piece of work, or a ready-made. I just knew that it was a bicycle wheel, and I loved that it was a bicycle wheel.

SCHWARTZMAN: Have you ever been star-struck?

BERMAN: That’s a good question. Yes. I’ve been star-struck in a sense. One of my oldest friends is Billy Gray, who was in a show called Father Knows Best. It was a huge show in the ‘50s and early ‘60s and he played Bud. So, when I watched TV, I realized that’s Billy, our friend, and I could not really distinguish between Bud and Billy, at all.

SCHWARTZMAN: What you do in the book, though, you have an admiration, almost, for things that have an artifice...

BERMAN: Yeah, what’s the artifice and what’s true? The one time I was star-struck as a child was with the Rolling Stones. And then eventually, I met Mick Jagger at the T.A.M.I. Show.

SCHWARTZMAN: At the run-through of the T.A.M.I. Show?

BERMAN: Yes.

SCHWARTZMAN: What’s more amazing is that it wasn’t the actual T.A.M.I. Show.

BERMAN: It was a dress rehearsal.

SCHWARTZMAN: You were, like, one of the four people.

BERMAN: My father went to the dress rehearsal. We were invited to stay at the T.A.M.I. Show, but my dad didn’t want to stay for the show, which was fine.

SCHWARTZMAN: Why not?

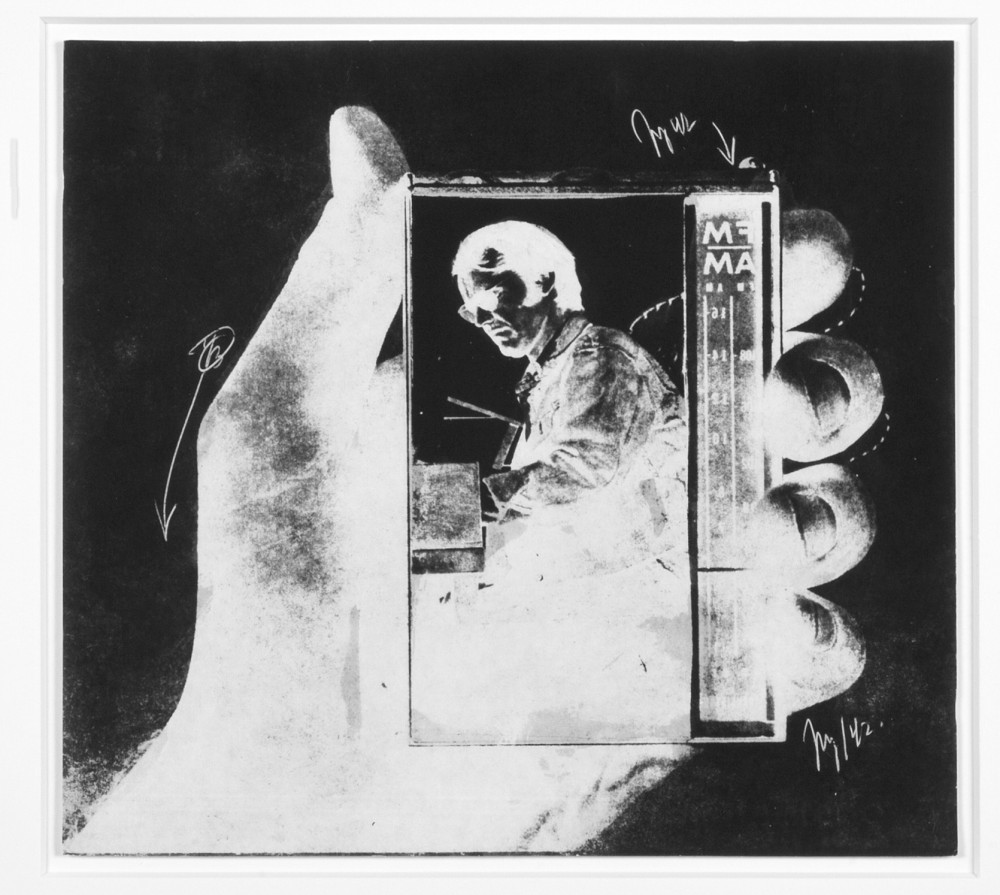

BERMAN: For some reason, he was not interested in seeing the whole show, I don't know why. Oddly enough, and this is going to go into my dad’s work, he always had an 8mm camera with him, and he was shooting whatever he found interesting. He had the camera at the rehearsals, and this was before copyright, you know, he just shot anything he wanted. And it wasn’t until the T.A.M.I. movie — the T.A.M.I. Show was a rock & roll variety show in the early ‘60s. It was taped at the Santa Monica Pacific, and it was, like, the Supremes, the Stones, James Brown did a famous, incredible performance.

SCHWARTZMAN: Beach Boys?

BERMAN: Beach Boys.

SCHWARTZMAN: All in one day.

BERMAN: All in one day. One time. When the movie came out in the movie theater, we saw it and my dad filmed it from the movie screen. So, it’s interesting that back then, he could’ve filmed it there, in person, but he actually preferred the distance of that world, like a filter.

SCHWARTZMAN: But this relationship to fakeness and Los Angeles, because to me, the book really is—I’m from LA, and you’re from LA—

BERMAN: I’m from Los Angeles.

SCHWARTZMAN: But there’s Los Angeles, San Francisco, London—

BERMAN: Larkspur.

SCHWARTZMAN: I love when we walk around and you say, “That used to be that, that used to be that,” but when I was reading the book, I realized that you were a kid in Los Angeles, but you were in Topanga Canyon and it was forty minutes to get to—

BERMAN: Thirty to forty minutes to get out of the Canyon. It was basically two lanes going in and out of the Canyon, so you’re between Malibu, Santa Monica, and then you have the San Fernando Valley on the other side. Canyon areas are very interesting to me because it’s a very restricted area, you know. You’re, sort of trapped between two worlds. I never felt like Topanga, or any canyon, is the world, it’s a bridge between two cultures or two societies. And, as a teenager, I did not like Topanga.

SCHWARTZMAN: Really?

BERMAN: It was dusty. To tell you the truth, it’s a secluded culture. The whole hippie thing was exploding, and I think the whole hippie culture-world was at its strongest and its greatest for a few months. And then, afterwards, it became a fad people with deep problems are attached to that culture, and Topanga to me conveyed the sour side of the ‘60s. You know, there’s people like Charles Manson in Topanga and stuff like that as well.

SCHWARTZMAN: You were put off in a way by the hippies. What I love in the beginning of the book is when you talk about your father and music being so important to him. Then, towards the end of the book, it’s all about you becoming a teenager and how much music meant to you. You escaped musically.

BERMAN: Music has always been my escape or my portal to another world, not a better life, but a more interesting life.

SCHWARTZMAN: Growing up, art was a major nutrient. As you, then, became a teenager, were you extra snobby? I don’t know how to say this. You are the most excited and adventurous person that I know. You’re always looking for more new music and new books. You’re always onto something.

BERMAN: I’m really hungry.

SCHWARTZMAN: I often wonder, as a person who was treated like a kid but with all the adults and who was welcome in a lot of exclusive spaces, how you still remain interested in things, and you’re still open to things. A lot of people would be like, “I don’t know. Uh, I saw that in real life, ‘the wheel.’”

BERMAN: Yeah. For example, I had certain taste as a child and as a teenager, but my father had really great taste. He had a great antenna. For instance, he brought in the first Velvet Underground album to the household, and to me that was like weird stuff. There was a song called “Heroin.”

SCHWARTZMAN: You talk in the book, too, about someone, injecting heroin in front of you?

BERMAN: Well, that’s different.

SCHWARTZMAN: But did you ever feel scared?

BERMAN: I felt very secure, very safe. My family is very structured; there was a mom, there was a father, had grandparents, when a lot of people in Topanga were, you know...some of the moms had a biker boyfriend or drug dealer. So, there was a sort of, wilderness. Among all these ruffians, I felt like I was Oscar Wilde.

SCHWARTZMAN: And then, when you got your car, had the music, you would drive people around. Were you always a sharer? Were you always into curating a moment in a way?

BERMAN: Yeah, ‘til this very moment, I am still a sharer. One thing I liked about school—the only thing I liked about school—was “show and tell,” where I think in the first grade or in kindergarten you take something from home and you show it to the public or to your fellow students. I loved that. I loved bringing a record, book, picture, whatever it was at that time, and to this day, you know, I started this press called TamTam Books and really, it’s nothing more than show and tell.

SCHWARTZMAN: There’s a story in the book that I don't fully understand. The Limited Edition story. Can you just talk about that for one sec?

BERMAN: As a child, I had a comic book collection, not as serious as other people’s collections but it nevertheless was my collection. It was Marvel comics that I was into. It was probably when I was like twelve or thirteen, fourteen, something like that. So, I became, sort of, obsessed, like, if I’m gonna get one, of course I have to have issue number two, and of course number three, and even though number four, sort of sucked, I had to complete it. So, I had a good inventory of comics, but not crazy, insane, amount, but a good, honorable collection.

SCHWARTZMAN: Right.

BERMAN: And I had piles. So, I looked at the top of the pile and I noticed on the cover was a stamp, “Collector’s Item,” not from the magazine itself. It was actually stamped.

SCHWARTZMAN: Collector’s Item.

BERMAN: The one below that: Collector’s Item. And, then below that: Collector’s Item. And then, I went to the very bottom, like number one—stamped: Collector’s Item. And then I looked in the drawer—I had a secret stash, unclassified comics that I hadn’t even put in inventory yet—Collector’s Item. So, I’m getting kind of creeped out. I realized every comic book was stamped “Collector’s Item.”

SCHWARTZMAN: You were scared.

BERMAN: So, my dad was home—my dad was always home—looking at the newspaper or whatever, and I said, “Dad, I have to talk to you about something really serious right now.” So, I tapped his shoulder to get his attention, and he looked over and said, “What?” and on his forehead was “Collector’s Item.”

SCHWARTZMAN: And then what was the moment after that?

BERMAN: I didn’t have a magazine collection anymore. I sold it or—I traded all my comic books.

SCHWARTZMAN: Why?

BERMAN: Because, I felt at the time, like it didn’t really ruin my collection. It just brought out how ridiculous it is to have a collection of something. Possession—it’s terrible. To possess something, like, collecting comic books is meaningless and stupid.

SCHWARTZMAN: Was that what it was? Do you feel like it was a lesson?

BERMAN: To me, that comic book collection was very important. But, I totally took the opinion that this is all pointless, you know? Though, it struck me as funny, because he did these really strong, crazy, practical jokes.

SCHWARTZMAN: You never sat down and talked about much. Ever?

BERMAN: Well, not in that sense, no.

SCHWARTZMAN: Right.

BERMAN: We never discussed why he did that. Like, was it funny? Was he trying to teach me something? And that duality is something I sort of lived with, and sort of, had to understand to not understand. I didn’t have a comic book collection afterwards. When you read the whole book, you’ll find pathways and roads. As a teenager, my dad had a collection of View Magazine. View Magazine was the official Surrealist publication in English from Surrealists who moved to New York during the war years. My dad had a complete View Magazine collection and his mother threw it out. I know he was totally upset about it. I think my comic book collection was a similar situation to him, but not like, “I lost my View magazines, therefore, I’m gonna destroy my son’s comic book collection.”

SCHWARTZMAN: You told me a story once, I had left something in a wrapper for a long period of time, and I said, “I’m afraid to ruin it, but then once it gets ruined, I kind of love it.” But then, you said something that really affected my life, where you talked about the mudslide in your home, and things being taken away.

BERMAN: Yes. We had a mudslide in our home, when I was like, ten—two days after Christmas. So, we had a mudslide that destroyed everything. I had nothing. The only thing I had was what I was wearing, and what was in my pocket at the time. So, I did suffer a great deal of physical loss, yes.

SCHWARTZMAN: Can I ask one really silly question? I hope it’s not too personal, while we’re talking about your memoir.

BERMAN: Yeah.

SCHWARTZMAN: Nowadays, when I’m with my wife and children, if we have a disagreement or something, there’s an effort to, you know, “let’s not talk about this now.” In a house, in that situation, how much were you aware of your parents’ relationship?

BERMAN: That’s a good question. Tell you the truth, in our small house I didn’t really notice anything, like, tension. They worked perfectly well together. I mean, to me it seemed like it. There may have been arguments and stuff. When you’re arguing it’s always upsetting for a child, but usually the next day, you won’t remember.

SCHWARTZMAN: Was he [Wallace] regimented? Just because his workspace was at your home, it gets blurry, the lines between when you’re working and not working.

BERMAN: He seemed to be always working.

SCHWARTZMAN: Always?

BERMAN: Yeah. I mean, it’s not like a 10-to-5 type of situation, but he always did work. He was always working.

SCHWARTZMAN: But you always could talk?

BERMAN: Yeah, but sometimes I’d talk and I would just sit there and watch him do his work, and sometimes I’d help him hold the frame. I’d put the records on. One thing he would do is play music over and over again. Like, he played forty-five singles, but I think he liked that format because it’s the perfect song, you know, ‘A Side,’ it had to be perfect. So, what I would do is play something like “You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling,” not once, or twice, but we’re talking like thirty times in a row. I would play Nat King Cole’s “Who’s Next in Line?” over and over and over again.

SCHWARTZMAN: Can you look at the art and separate it from the music or no?

BERMAN: Well, for him, I think it’s a way for him to focus on the artwork. He loved working with music. He also played Paul Bowles’ recordings of Moroccan musicians, which are very chanty, very hypnotic. So, I think a Phil Spector record used in the same format, you know, it was very hypnotic.

SCHWARTZMAN: When you would talk about art or music, could you guys disagree with each other?

BERMAN: No, because we never had discussions like that.

SCHWARTZMAN: I have one last question for you. What are you reading now, or listening to now, that you’d like to share with everyone now as a recommendation?

BERMAN: Vic Damone’s Greatest Hits. I find it the missing link between Scott Walker and Jack Jones. And, Stravinsky’s very minor work that nobody knows—he did a disco record. (grins)

SCHWARTZMAN: How is it?

BERMAN: Well, it’s for the Ballets Russes, so it’s a very early disco record that he and Picasso put together. I’m the only one who has a copy of this. It’s very expensive.