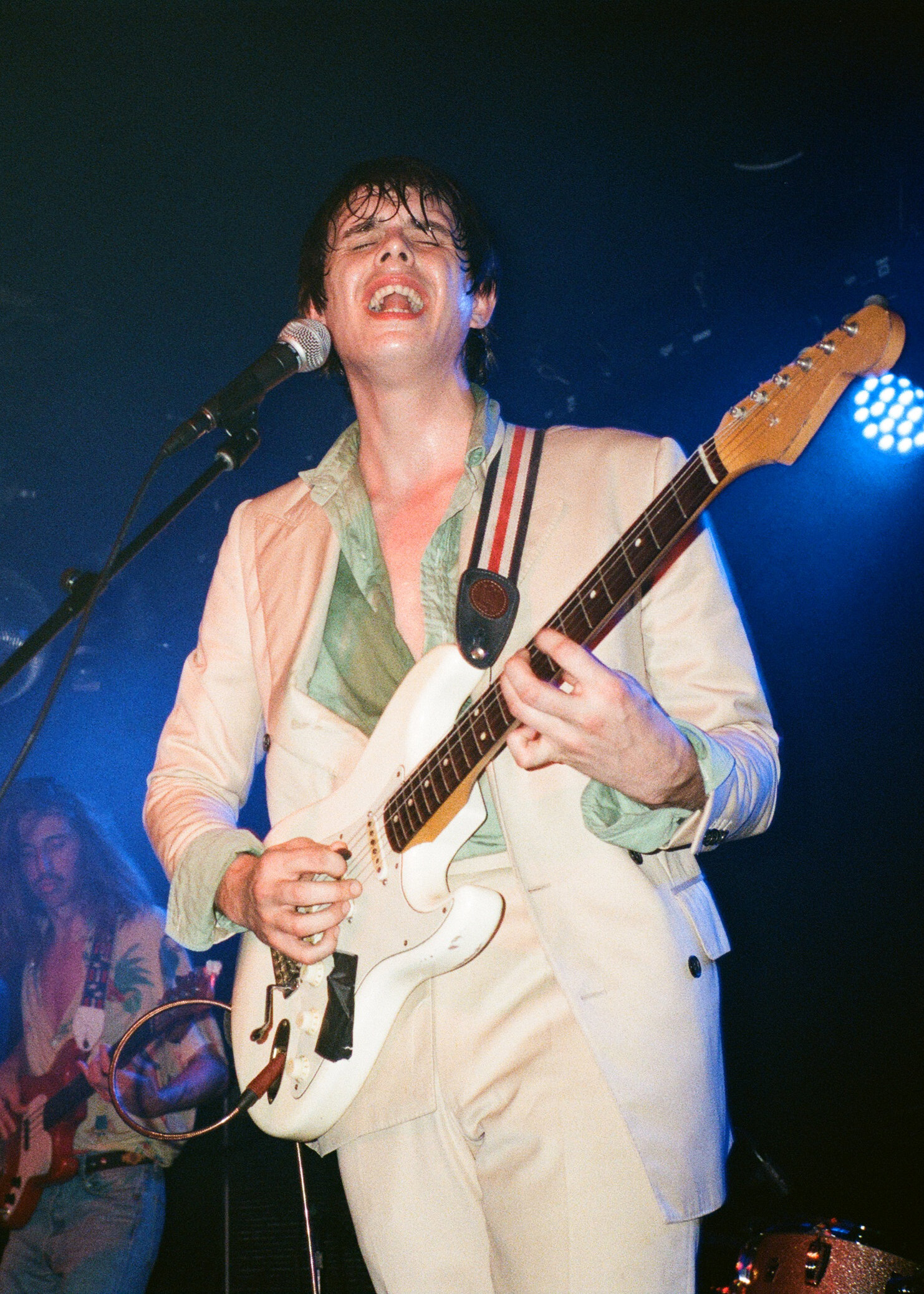

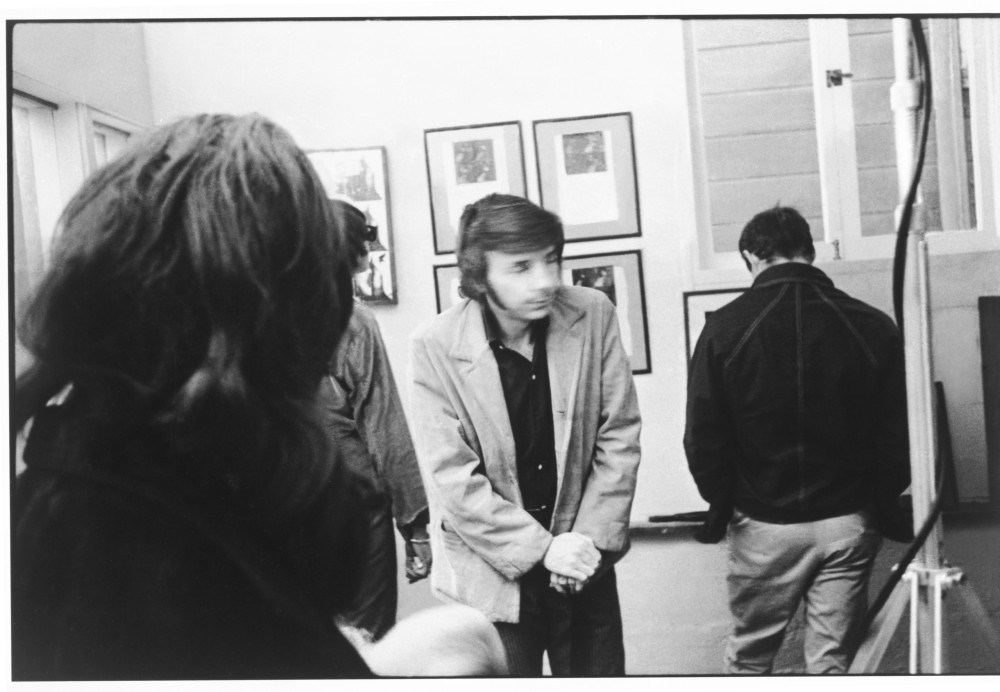

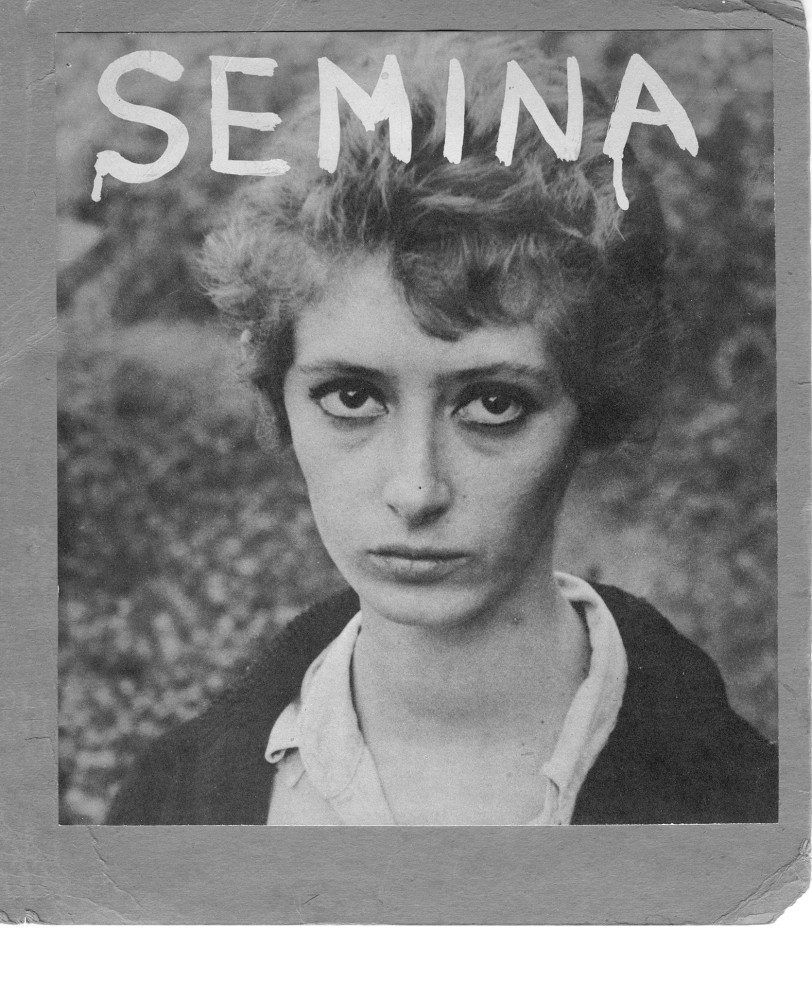

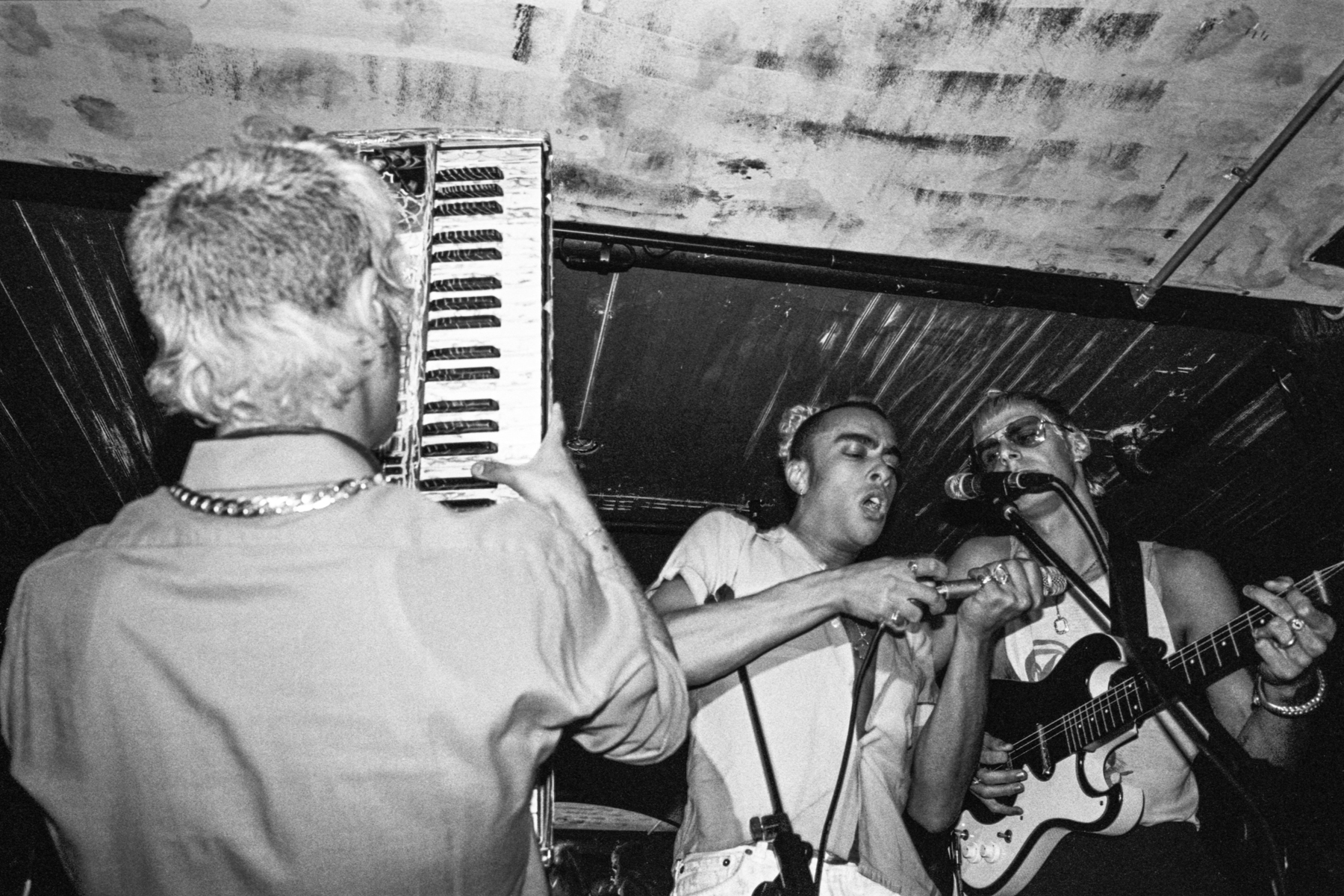

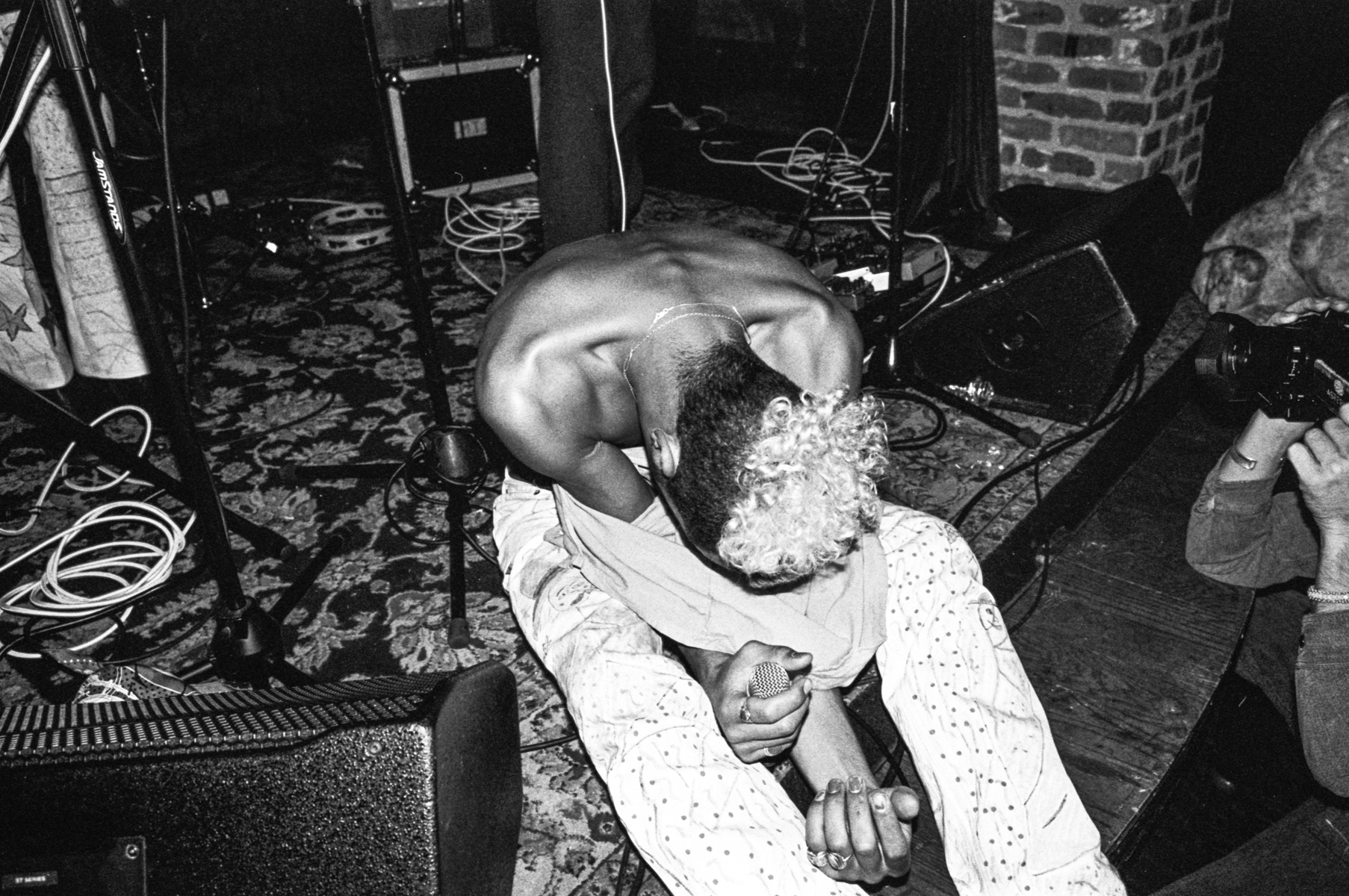

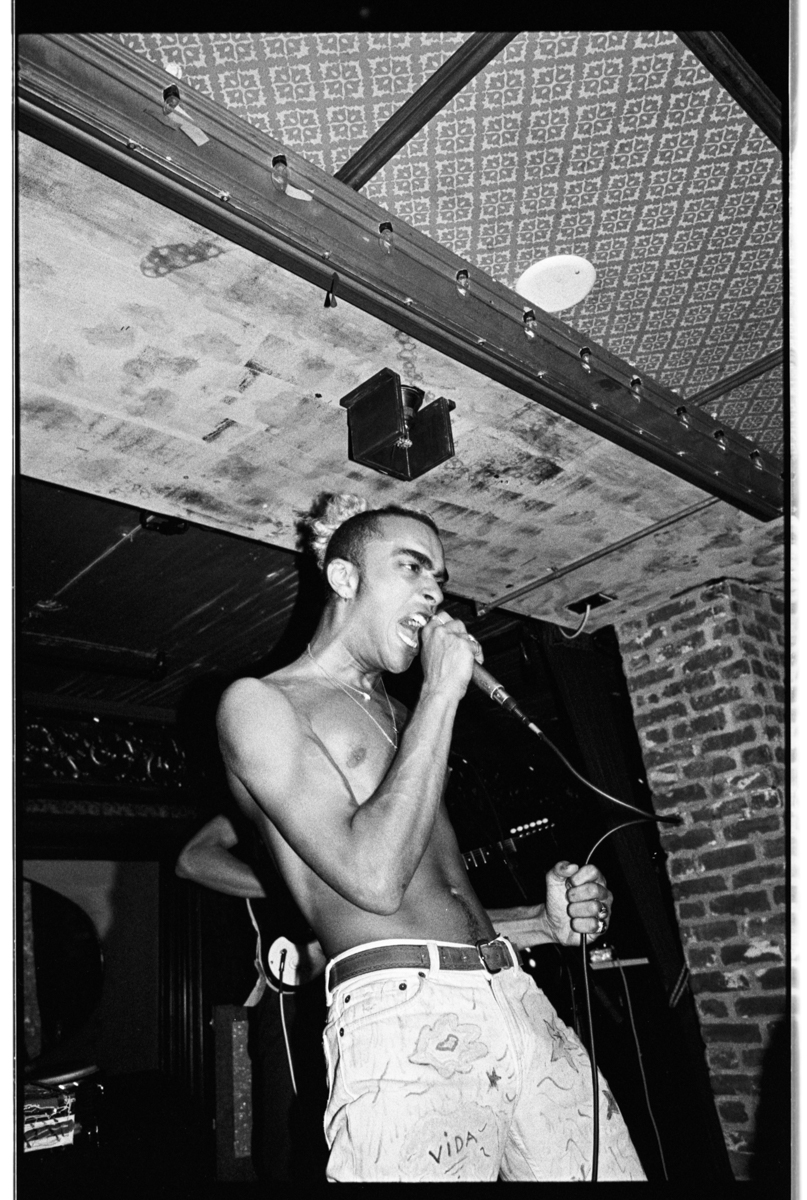

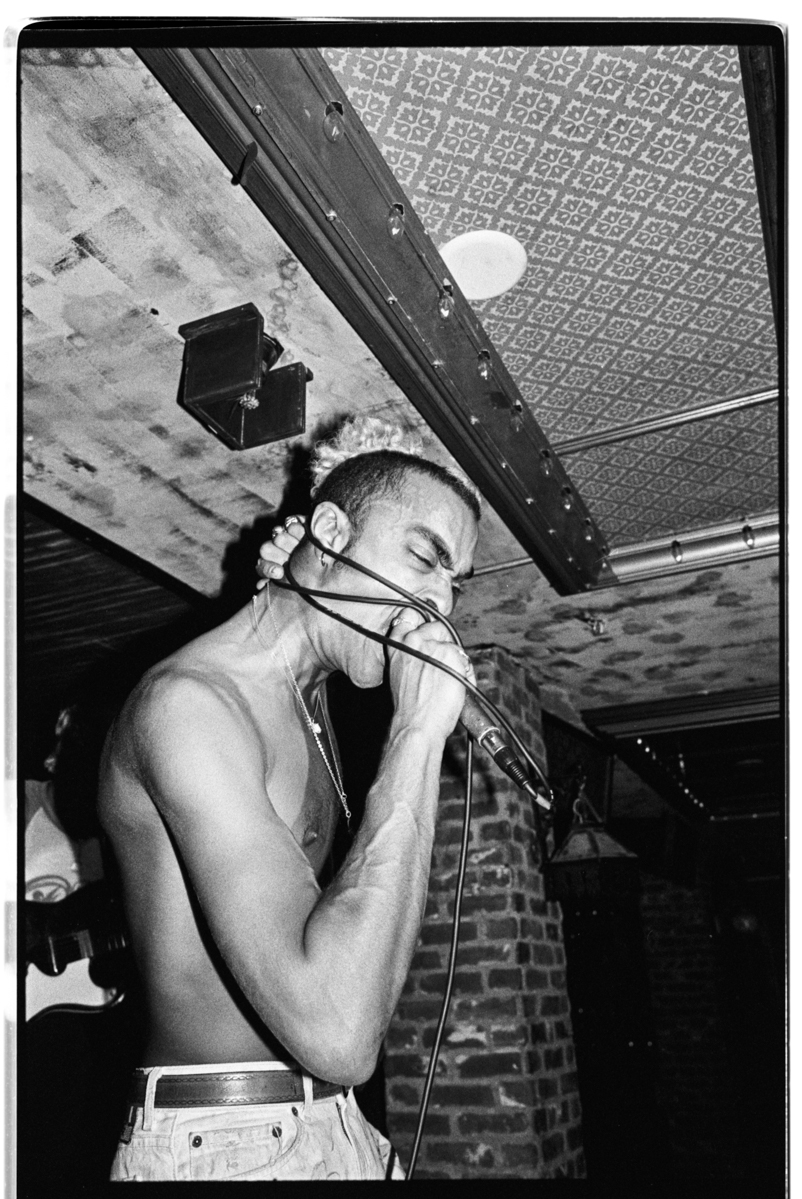

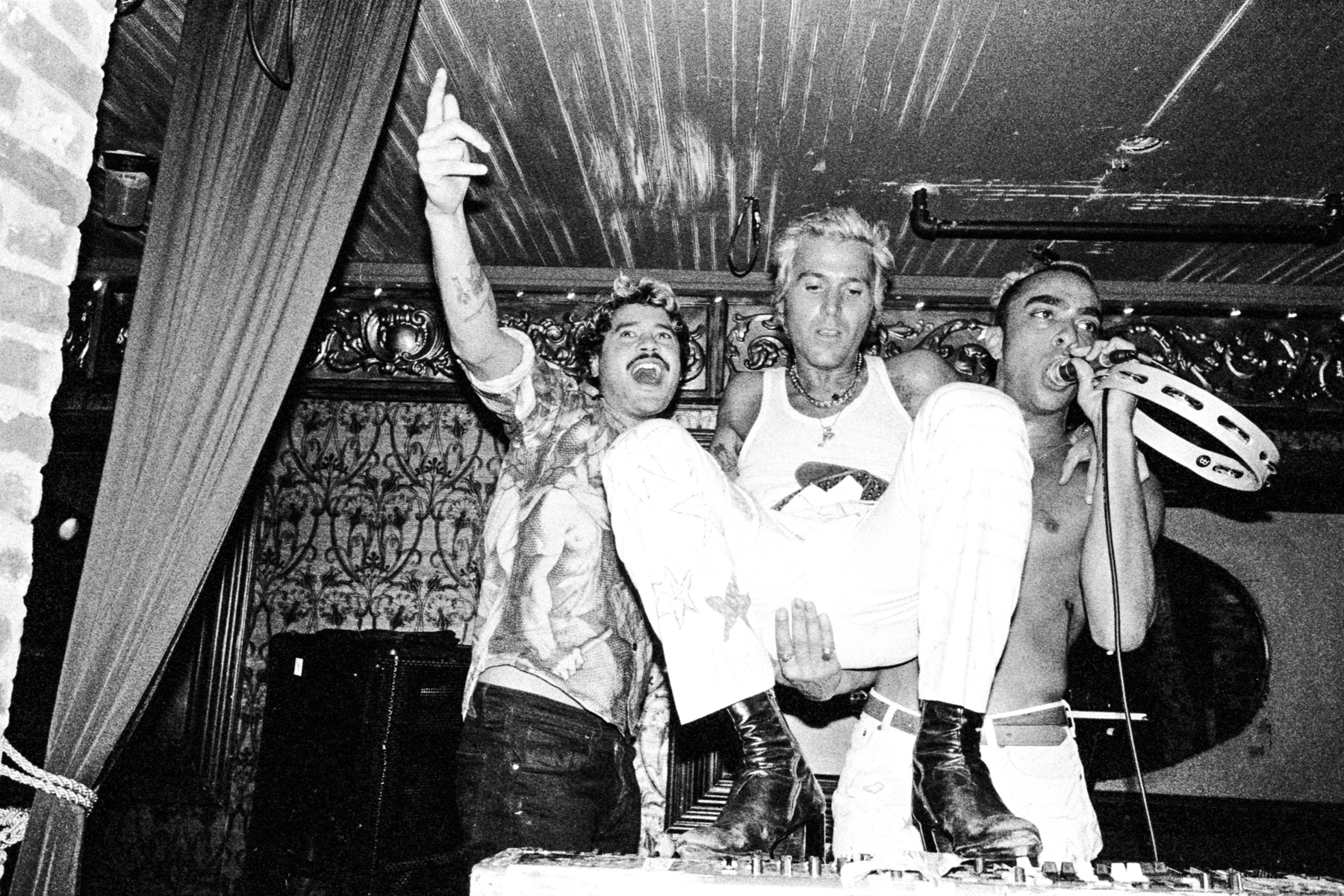

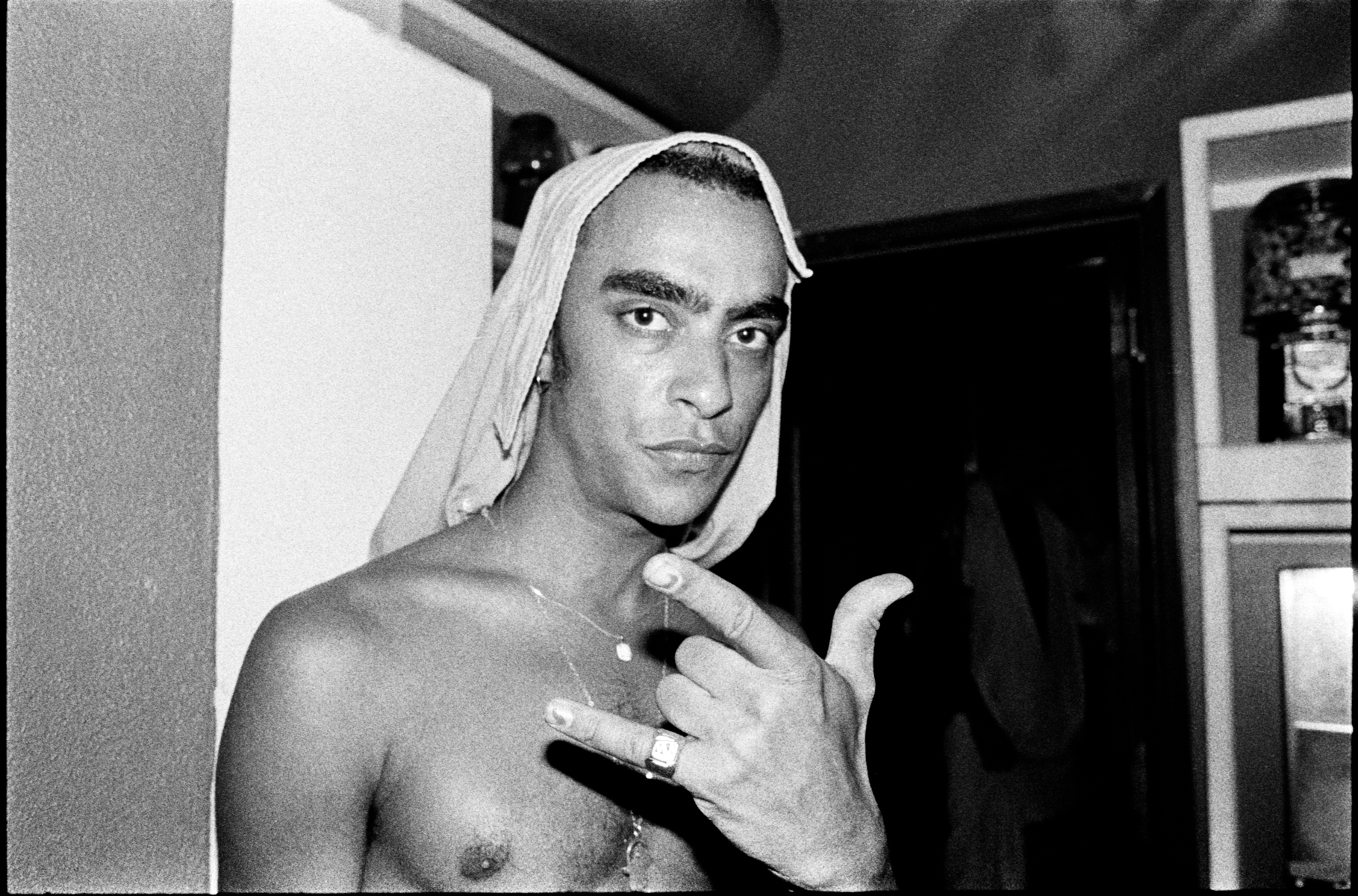

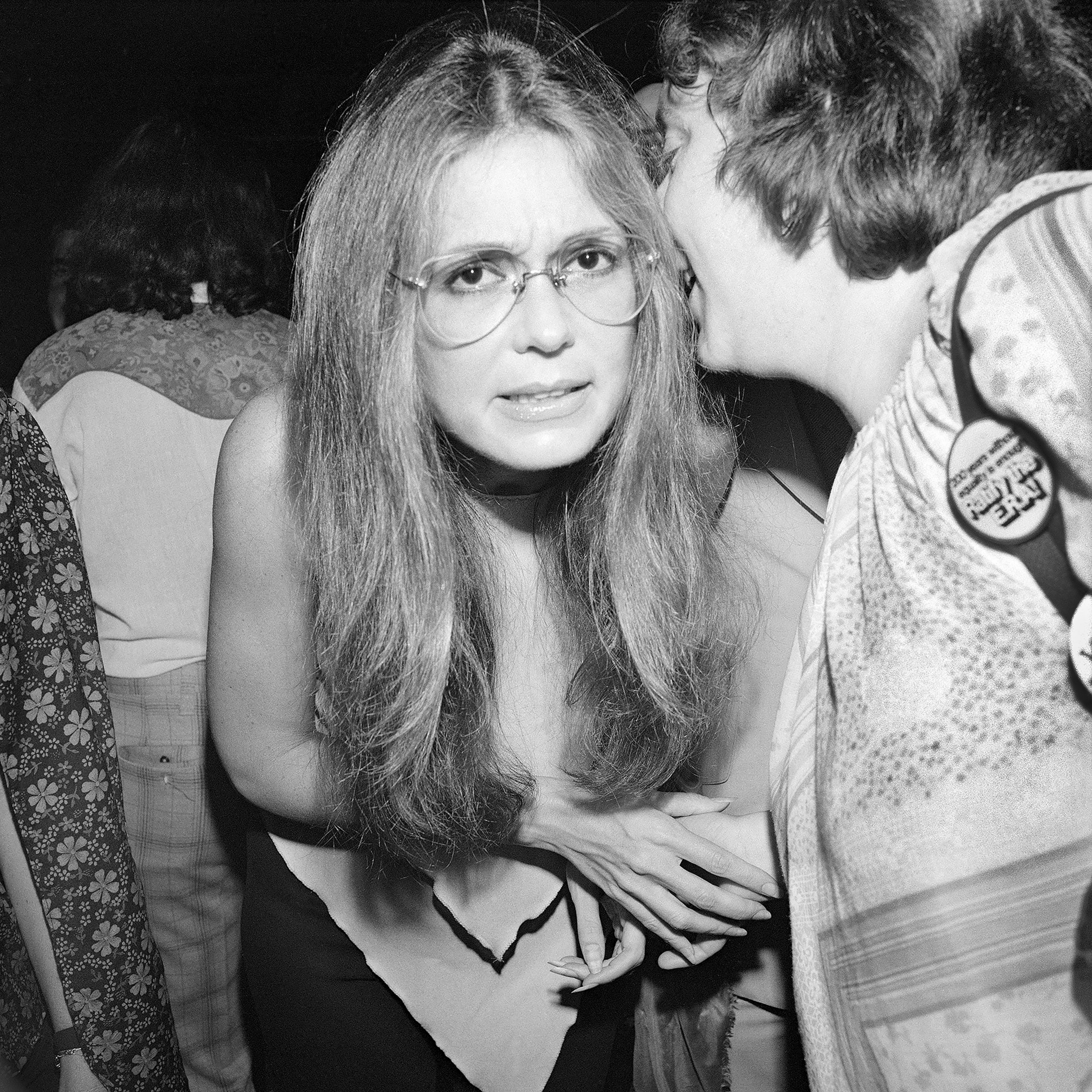

Photo by Charlotte Ercoli

interview by Emma Grimes

Maya Man is a New York-based digital artist whose work probes the changing landscape of identity, femininity, and authenticity in online and offline culture. Through websites, code, and generative AI projects, she explores how we perform ourselves in digital environments.

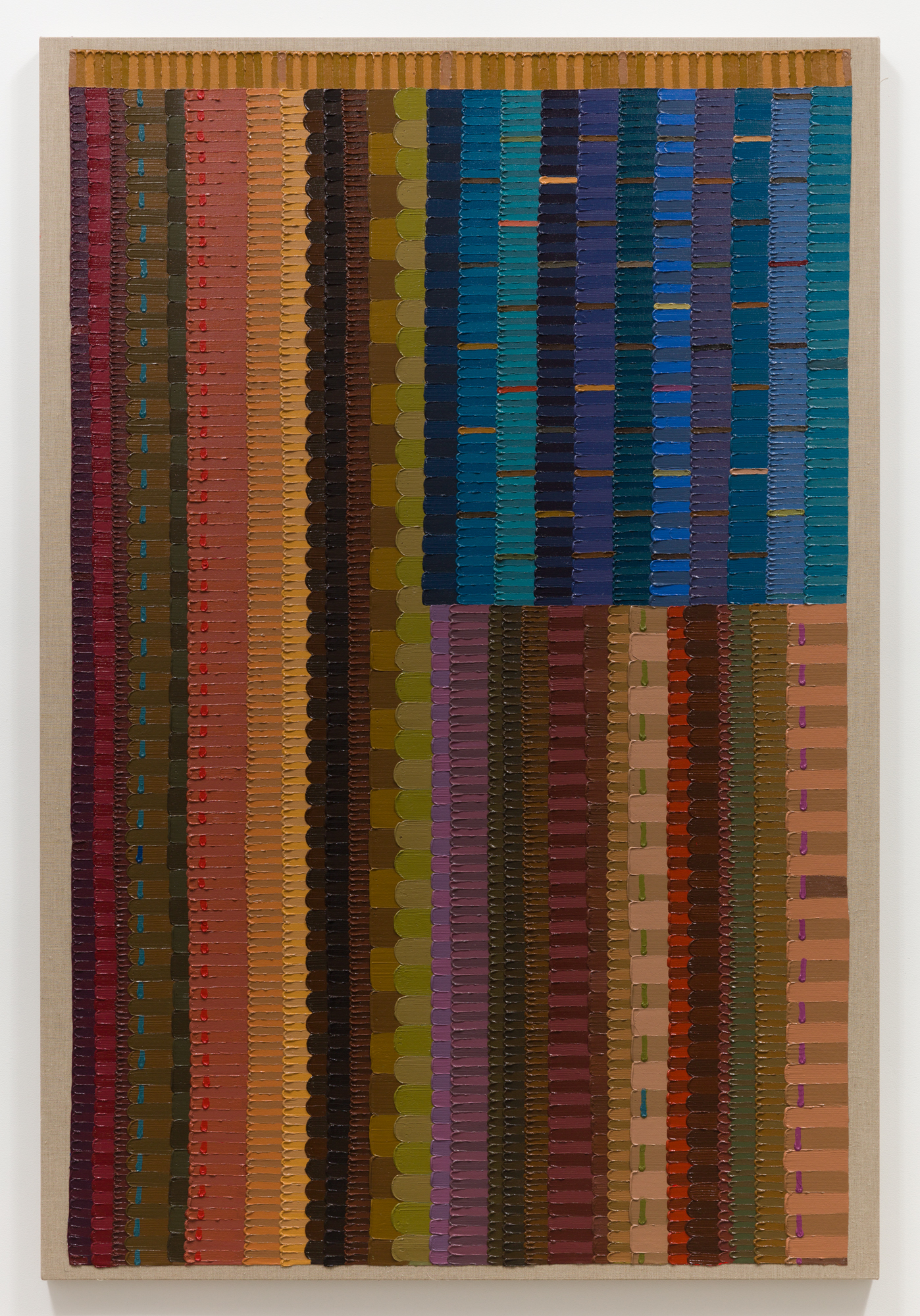

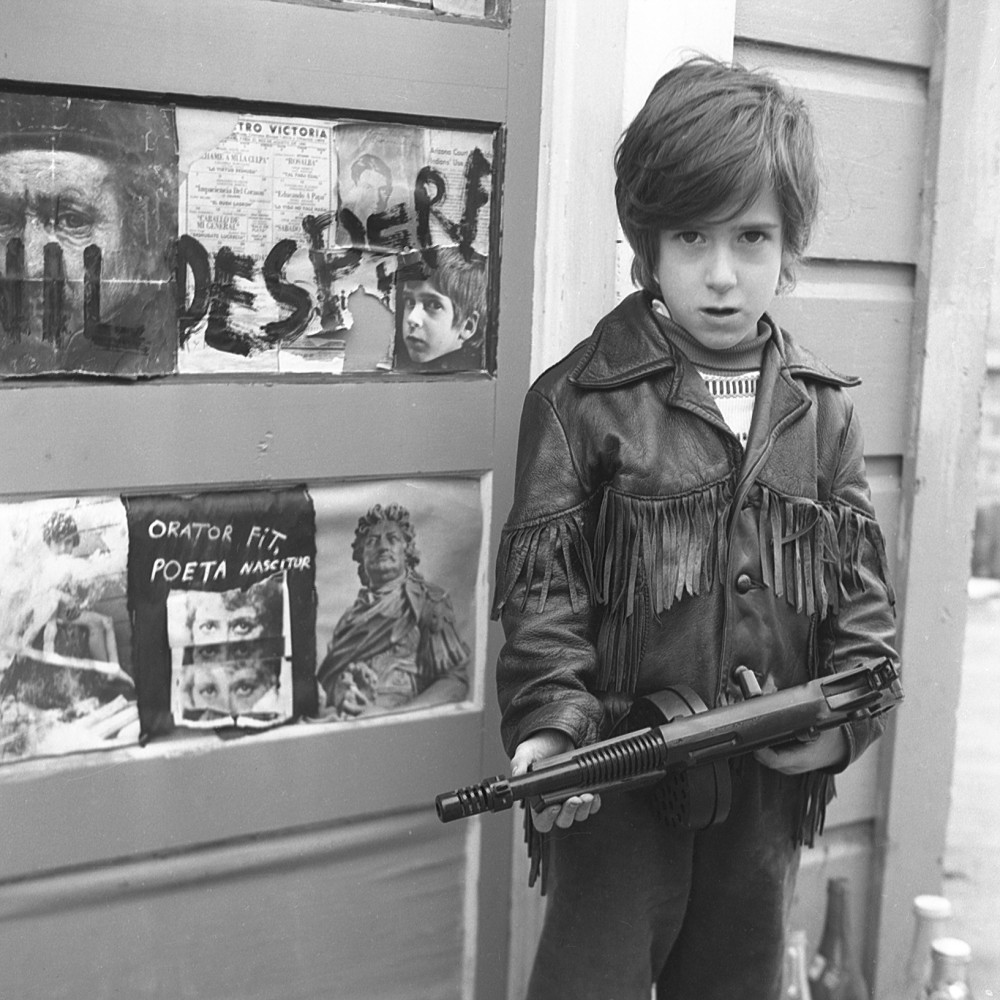

One of her signature projects is Glance Back, a browser extension that randomly takes a photo of users on their computers every day. Created in 2018, the project archives what Man calls “the moments shared between you and your computer,” turning everyday encounters with our devices into a digital diary. She is also the creator of FAKE IT TILL YOU MAKE IT, a coffee-table book that compiles her generative artworks styled after the glossy and aesthetically pleasing graphics and phrases commonly found on Instagram.

Central to her practice are questions of authenticity and performance: what does it mean to perform and post on the internet today? Is performance inherently corrosive or just another facet of human expression? For Man, she tackles these questions with thoughtful nuance.

Her latest project, StarQuest, is a solo-exhibition currently on view at Feral File. Drawing on her own childhood as a competitive dancer, Man uses generative AI to restage the choreography and interpersonal dramas of the cult reality series Dance Moms.

EMMA GRIMES: You’re interested in how we perform ourselves online. Where did that fascination begin?

MAYA MAN: I’ve been interested in self-presentation online for as long as I can remember. I have always felt uncomfortable about posting, but continued to post anyway. I started to realize when I was younger—in middle school and high school—how dramatically what I was consuming online affected my sense of self.

GRIMES: Which artists have most shaped your approach?

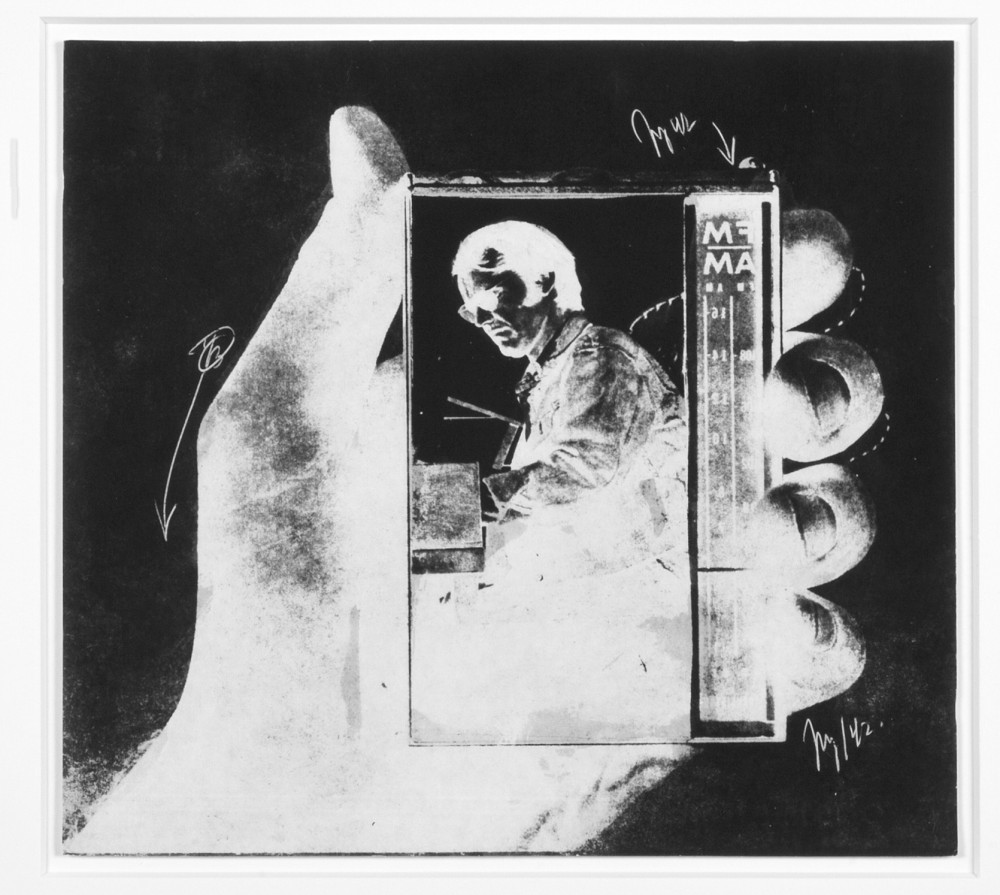

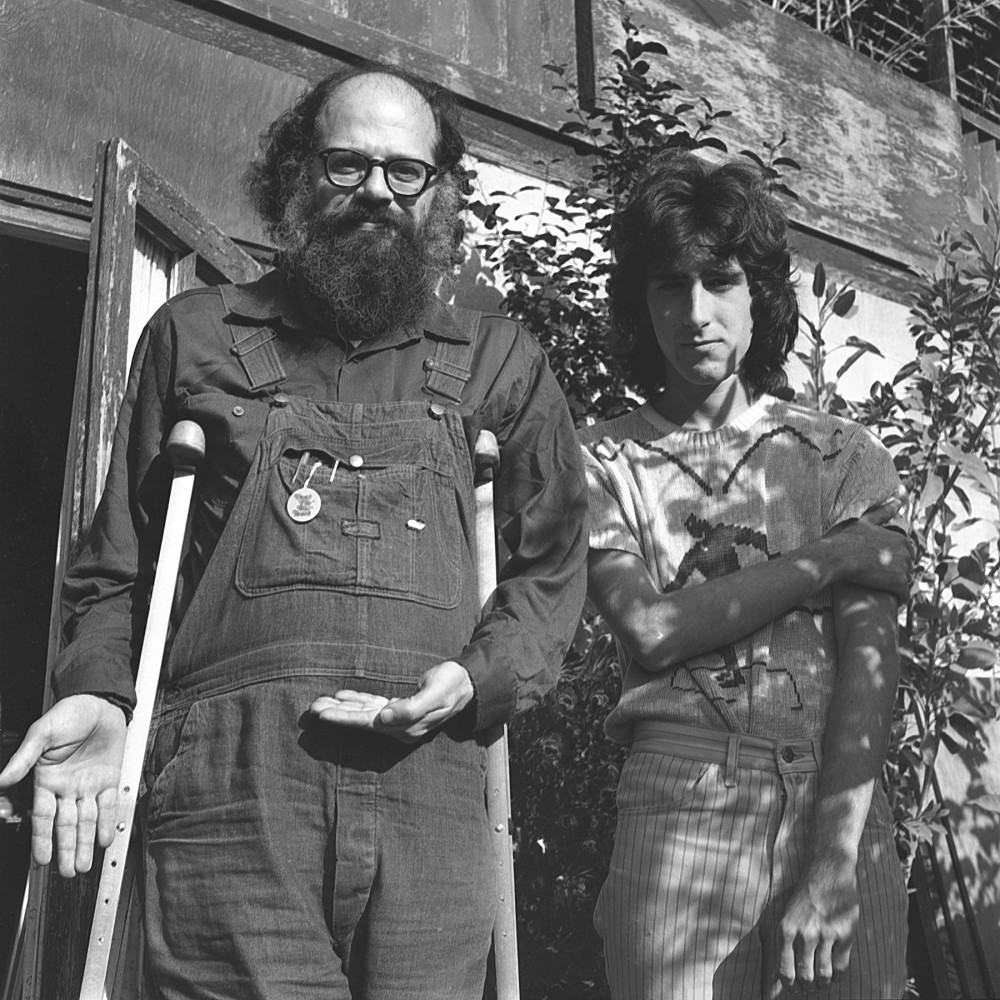

MAN: I’m really influenced by a few different movements. The first are artists who have used the computer as a tool, including Manfred Mohr and Vera Molnar. Also, the net.art movement in the ’90s and the early 2000s, when a lot of artists were creating websites as art objects and thinking about what it meant to be able to distribute work in a networked way. I am very moved by the work of Olia Lialina, JODI, and Auriea Harvey. One artist I really admire is Lynn Hershman Leeson, who was making work in the ’60s and ’70s about the performance of identity. And artists like Ann Hirsch or Molly Soda, who also were thinking about performing gender online. Cory Arcangel’s work has been important for me because he shares an interest in both pop culture and code. I’ve always felt that I exist between these two worlds. There are artists who write code and use software as a medium that I resonate with, but a lot of the work—these are generalizations—tends to be more abstract or geometric, or more formally driven. Then there’s artists who are really thinking about performance online that I feel conceptually tied to, but less often they’re writing custom code or as interested in using generative tools.

GRIMES: What does a typical day in your studio look like?

MAN: A realistic day in my life. (laughs) If I’m being really honest, I work best at night. If I’m really working on something, I’m likely making it between the hours of 8 PM and 3 AM. I always wish I was different, but that’s how I am. I come to the studio quite religiously, almost every day. I am very lucky to have this beautiful, large space in SoHo, but I spend most of my time in one corner on my computer with my monitor. It’s a lot of clicking around, and it’s different every day. I could be in the early days of researching a work, I’m asking myself, what’s the best way to build it or what tools make sense for this system, etc. More recently, I’ve been working on an AI-video-based work that required a lot of research before deciding on the right methodology. There’s a lot of research, there’s the studio work, and there’s a lot of administrative work too. And it almost all happens on my laptop.

GRIMES: How do you think of authenticity? Do you think we’re ever not performing?

MAN: My philosophy of authenticity is that it doesn’t exist in the way people wish it did. I don’t believe it’s possible to perform in a way that’s authentic. People will say, I just post for myself, which is a lie. They say that because they feel it’s morally better to be that way, and I really disagree with that. It’s okay to feel like you’re performing and even want to perform a bit. That’s not evil. It’s a condition of living. I’ve adopted a [Erving] Goffman-esque philosophy of performance online. Everything is a performance. Goffman was writing before the internet, so he is talking about socializing in general, which I also think is true. It’s been kind of freeing for me to subscribe to this notion that authenticity does not exist.

GRIMES: How has your relationship with social media shifted over the years?

MAN: I’ve been thinking about this a lot in the past year. There’s a general sentiment that social media has gotten a lot worse. I call it the “LinkedIn-ification” of Instagram. My relationship with social media is really quite professional at this point. That wasn’t true when I was twelve. I was just posting whatever. Posting feels like such a large and weighted act now.

GRIMES: In your essay about the story behind your recent lecture and video performance on Dance Moms, you compared the choreography of competitive dance to posting on social media. Can you expand on that?

MAN: I’m very excited to talk about this. It feels like a strange homecoming for me, almost, because I grew up as a competition dancer. I grew up in central Pennsylvania. Dance Moms takes place in Pennsylvania. I realized that the mechanics of the competition dance ecosystem, training in the studio, performing at competitions, then being ranked and judged, are very quantified. You’re getting data as feedback. It’s such a perfect analogy for what it feels like to perform on social media. I’ve been thinking about Instagram etiquette as a type of choreography that you learn by being on the platform. There’s what to do and what not to do. Everyone accepts that and mostly operates within those boundaries. Those who are the best at it have the most followers and likes. They understand the system. They’re able to execute a certain choreography of posting that’s rewarded in that system.

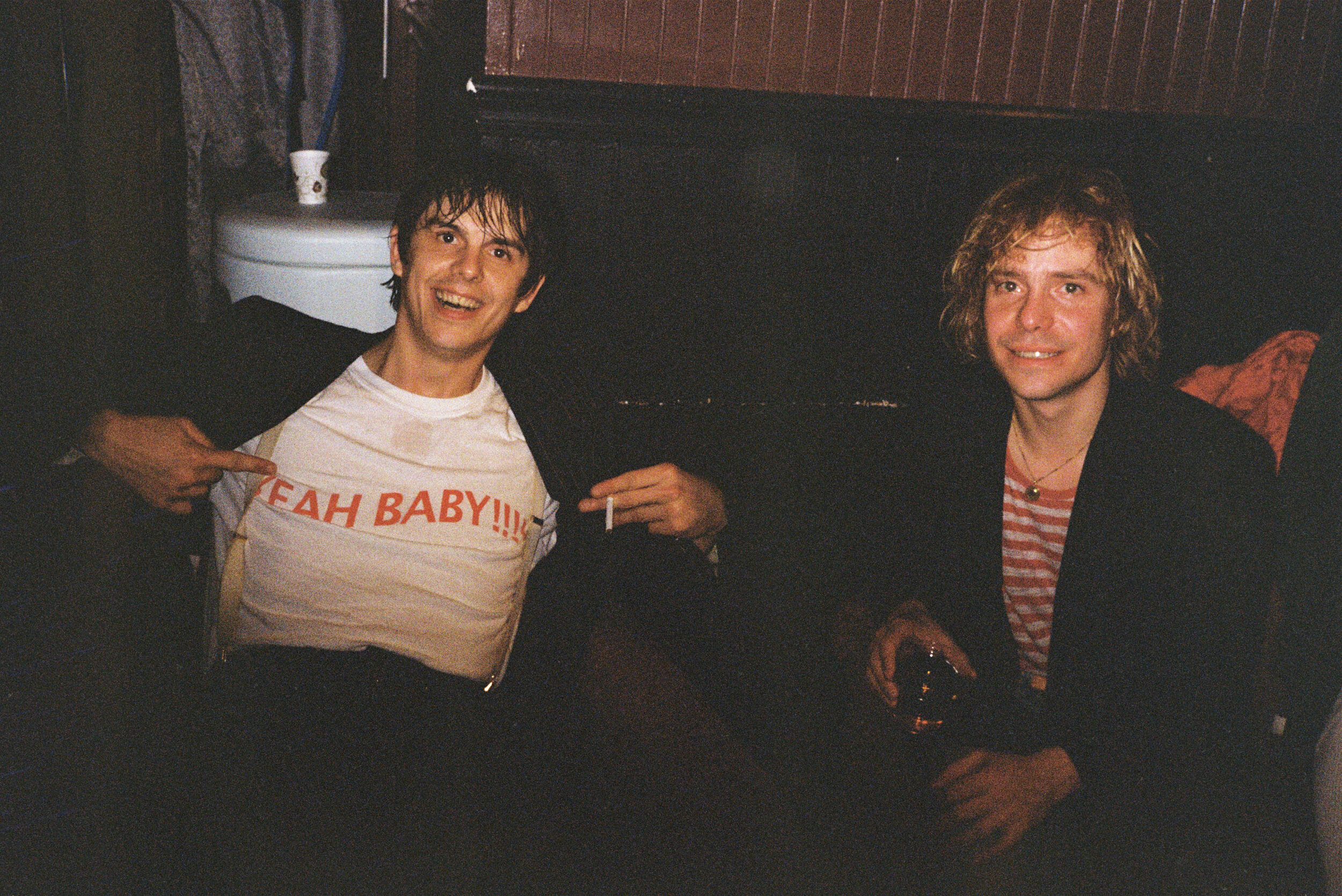

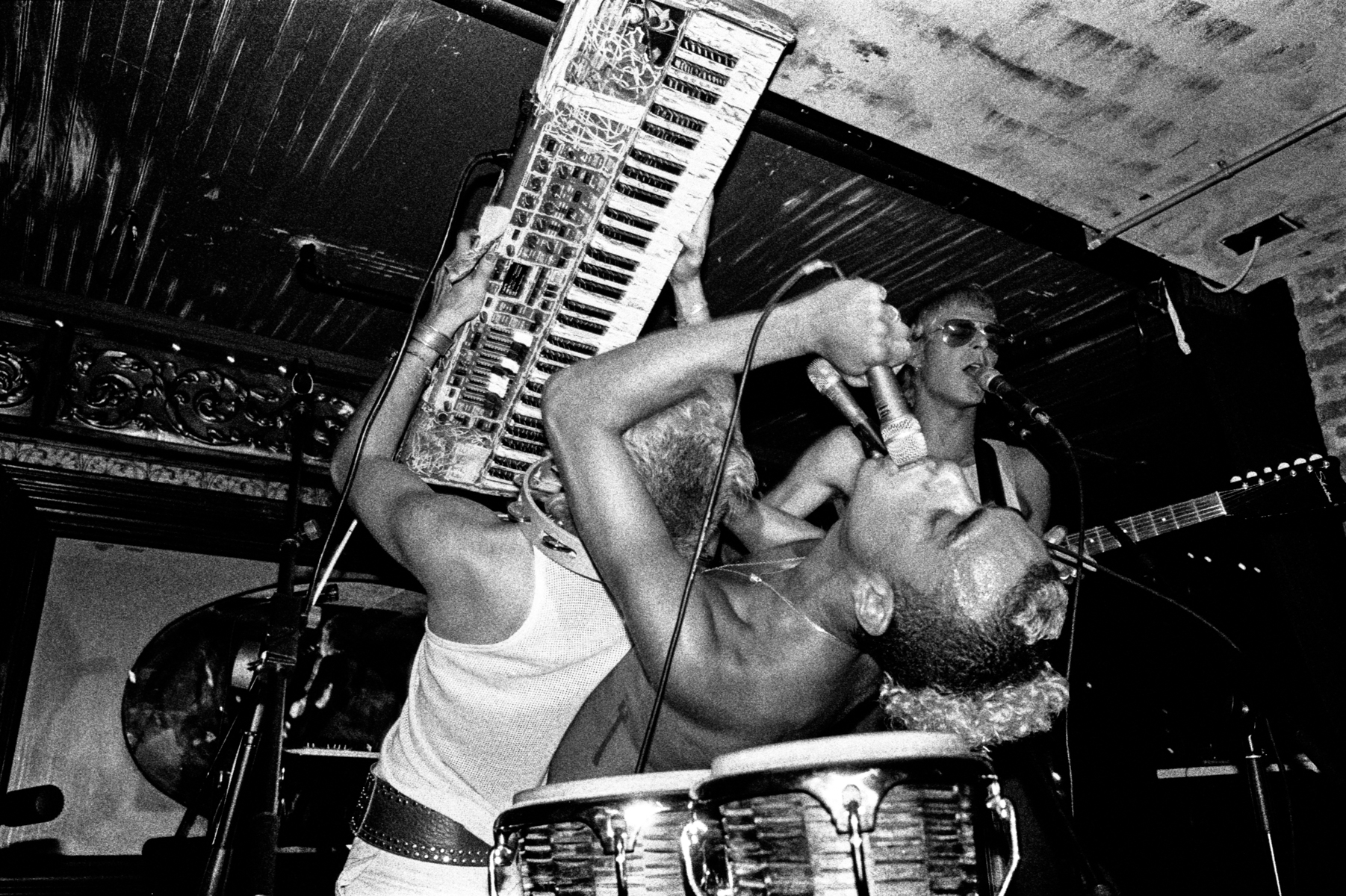

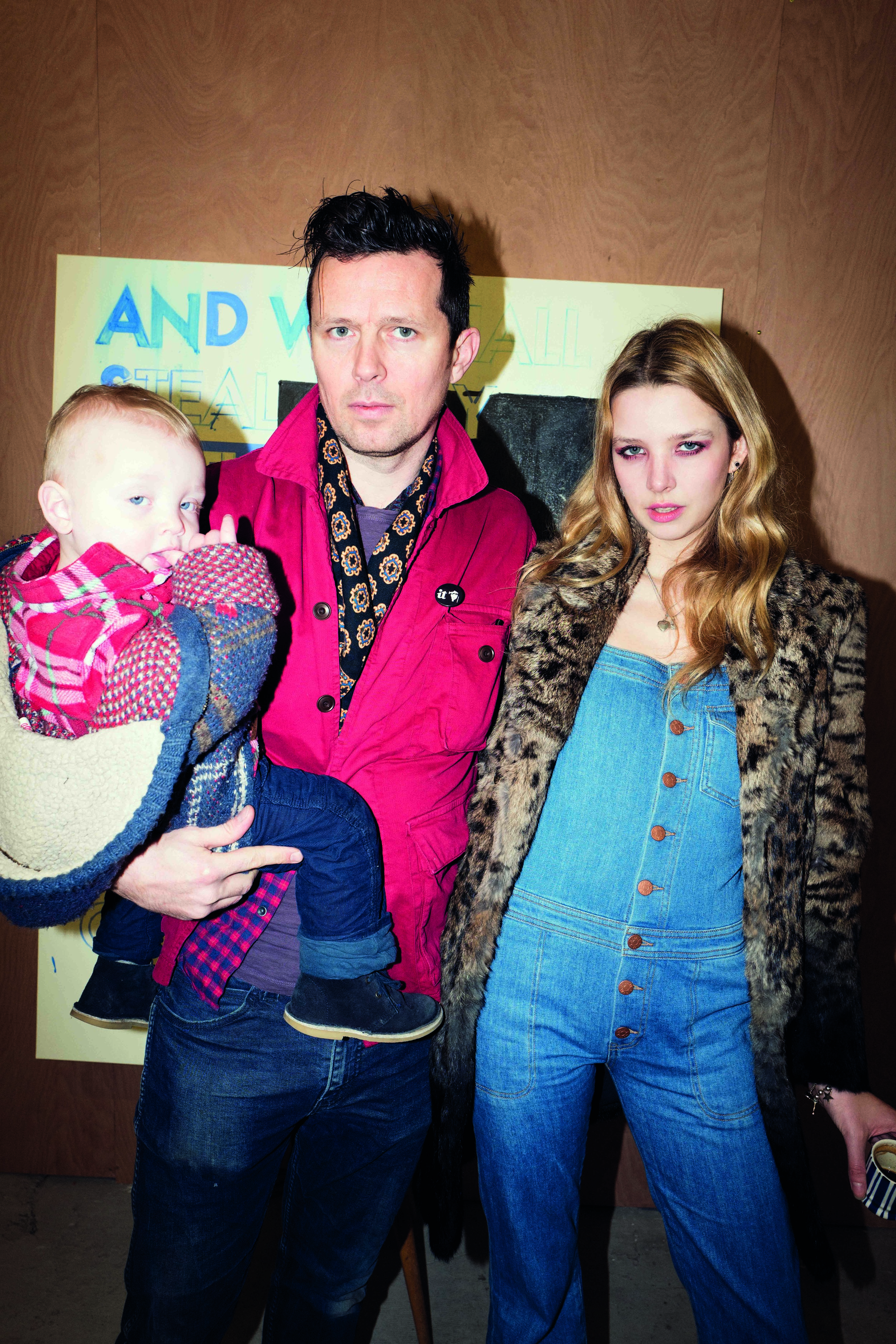

Man in her studio

GRIMES: I’m sure you came across the Harper’s piece a couple years ago by Barrett Swanson about the TikTok clubhouses—

MAN: Yes, that piece was so major for me. I remember reading it so vividly.

GRIMES: He wrote that we’re “cheerfully indentured” to posting online. Obviously, this was published a couple years ago because I thought, well, we’re definitely still indentured, but I don’t know if it’s so cheerful.

MAN: I think the sentiment has changed radically post-pandemic. I don’t feel like it’s very cheerful. It feels quite obligatory and business-oriented.

GRIMES: You’ve written about John Berger’s idea of the “surveyor” and the “surveyed,” which reminds me of a moment from The D’Amelio Show when Quen Blackwell, another creator, was discussing the camera and said, “It’s a third person that’s not existed to any other generation.”

MAN: I thought that moment was shocking in the show. The Berger quote is like “a woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself,” which implies this third person. And Quen, on The D’Amelio Show, just perfectly articulated that. That’s what social media platforms online create—this sense of a third person that isn’t anyone so specific, but it’s this implication of surveillance, that people are seeing you. I used to feel like there was something wrong with me because I felt like that all the time. Reading [Berger] and others has helped me figure out how to operate within that structure rather than try to escape it fully.

GRIMES: It’s a new condition to being online, but I also wonder if it’s also a new way of being human and of perceiving ourselves, of constantly being fragmented as a person.

MAN: Do you know the book series The Confessions of a Shopaholic? This has stuck with me since I read it when I was probably twelve. There’s a way the protagonist talks, like she’s shopping in a store and says things like, “Imagine, I get this red jacket and everyone will see me wearing my red jacket and will think, oh, there goes the woman with the red jacket.” This process of latching onto something and imagining others associating it with you, and that association strengthening your character or positive perception in other people’s eyes. Posting is all about that. It’s like, Oh, what if I posted this photo of a ribbon on the ground on the sidewalk? Then everyone’s gonna think, she’s the kind of person who would post this photo. I find it fascinating. It’s so much of what identity actually is. So much of what I would tell someone about my identity are things external to me, things that I have decided to attach to myself. For example, the artists I mentioned at the beginning of this interview. I want people to understand that I identify with them, and this will create this collage of me. But, it’s all very malleable.

GRIMES: Do you think it’s possible to disrupt the self-surveillance that these systems—social media, competitive dance, even the experience of growing up as a girl—produce?

MAN: This has been an experience—a very feminine-coded experience—that young girls have known for a very long time. Social media exacerbates that feeling of being watched, but it’s not necessarily the source of it. The source is the way that gender is performed and conditioned in culture. I don’t have delusions about escaping it or ending it. But there’s a certain level of awareness of it that was freeing for me. Also, I think there’s a tendency for artists’ work to be read in a black-and-white way. I’m making work about competition dance culture because I have criticism of it. At the same time, being a competition dancer shaped me in a million positive ways. It taught me so much about friendship, discipline, and being in public and performing in a way that was valuable to me. It’s complicated.

GRIMES: You recently debuted your piece and performance-lecture, StarQuest, in New York City. Can you talk about the project and that experience?

StarQuest, my new competition dance-focused series produced with generative AI, just had its first public premiere as a one-night installation and performance lecture co-presented by Triple Canopy and Feral File at Gibney, a dance studio downtown. It was my dream way to introduce this work, as both a site-specific installation and performance-lecture that walks through the piece’s many different elements: AI-generated video, competition dance, online performance, and the instability of “reality” today. The performance-lecture aspect was important to me because it requires the attention and presence of an audience which is difficult to capture sometimes when making browser-based work. It mixes a traditional lecture format, with choreographed slides, with staging and movement. I perform the TikTok dance renegade three times in it.

GRIMES: Lastly, what keeps you inspired every day?

MAN: Every day, I walk to my studio in SoHo from my apartment in Chinatown. I walk past a lot of tourist shops, and they have all these keychains, colorful shirts, and snow globes. They’re all just about loving New York. They’re about someone visiting New York and thinking, Wow, it’s New York, and then buying that to take home with them. It’s a bunch of mass-produced, cheap objects that represent something very endearing to me, which is loving and being so happy to be in New York City, and wanting to express that through an object. I find it very moving.