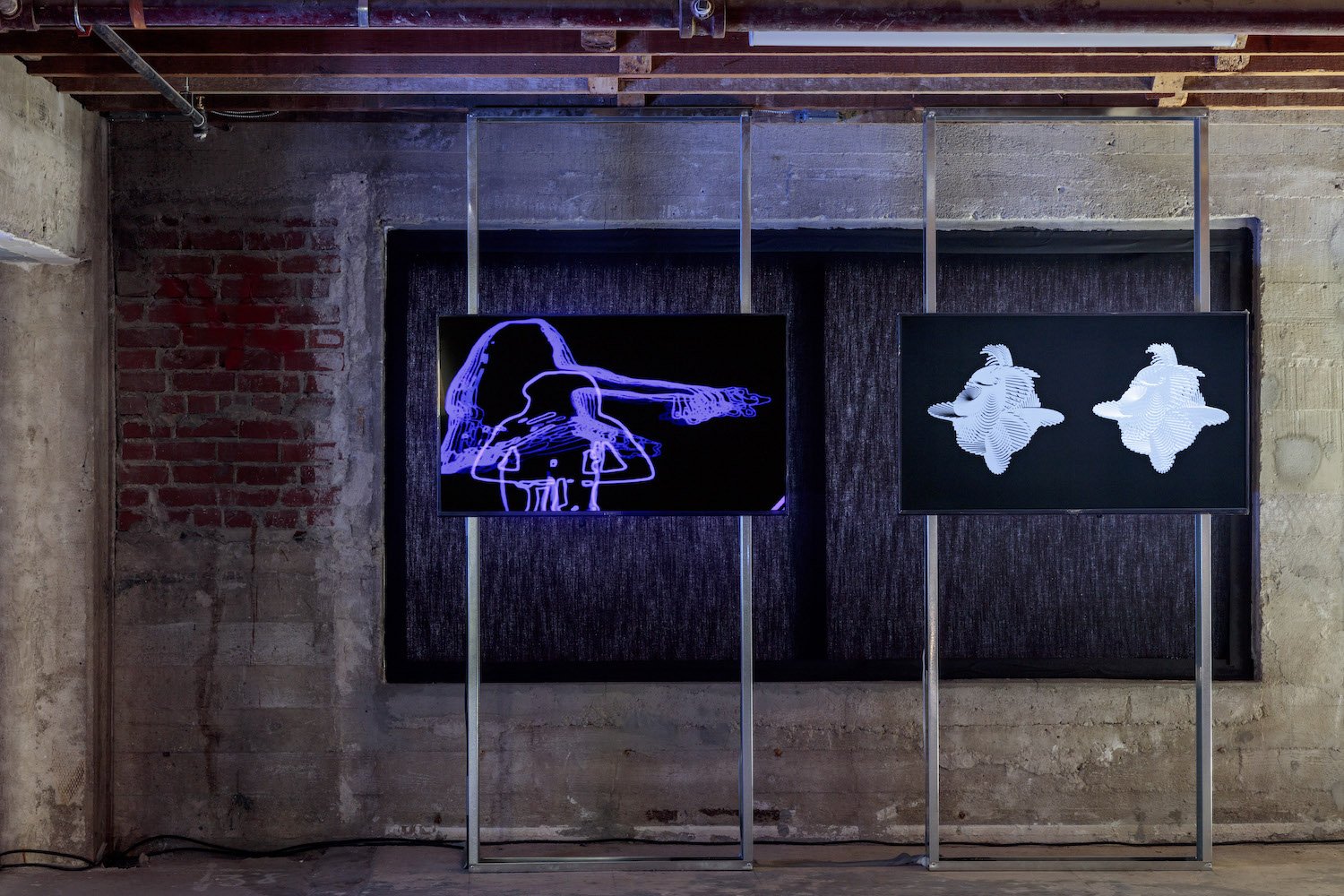

Alida Sun, Southern Gothic Love Letters to My NSA Agent, 2023, courtesy of the artist, bitforms gallery, and PR for Artists. Image by Joshua White

interview by Coco Dolle

NFT Tuesday LA co-founder and former Night Gallery co-owner, Mieke Marple is a Los Angeles-based artist and writer determined to navigate what she calls the “insurmountable chasm” between the physical and digital art worlds.

In her passionate mission to reconcile both the analog and the digital, Mieke has recently curated an impressive exhibition titled Interreality, showcasing 35 artists from the pioneering digital space mixed in with traditional established artists. Produced by Steve Sacks, founder of bitforms gallery and Aubrie Wienholt, founder of PR for Artists, Interreality is simply a tour de force.

A kindred spirit and peer curator, I was thrilled to interview Mieke to speak about the exhibition as we tackled notions of provenance, embodied experiences, collecting art and feminism.

COCO DOLLE: The recent groundbreaking exhibition at LACMA, Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age was enlightening on the symbiotic formation of tech and art. Tell us how your curation took inspiration from this show and about how it led to the making of Interreality.

MIEKE MARPLE: This exhibition was such an important moment in the digital art community, with the legacies of computer-based art, which had always been on the fringe before, finally getting canonized. These thematic, institutional shows are really important, but they can make artists feel sectioned off from the larger conversation and that's what I really wanted to do with this show. To have digital art be more seamlessly integrated with the larger, more mainstream conversation.

DOLLE: Artists reacting to the world they're living in integrating new technologies with new tools. There was really no equivalent to this show in New York. Two years ago, MoMA had a drawing exhibition titled Degree Zero, illuminating new visual languages in midcentury art. I was extremely pleased to see works by Vera Molnar along with Louise Bourgeois. And what about your choice of venue, a 15,000-square-foot space strategically located near LACMA. Was it a raw space when you found it?

MARPLE: Yes, it’s a hundred-year-old building. The owners recently gutted and retrofitted it and that's why it was available. It wasn't even rental ready. It didn't have outlets, or even real walls, or anything like that. But it's interesting to hear you say that this discourse with digital or computer-based art is further along in LA than New York. LACMA has definitely helped pave the way there.

DOLLE: Yes they also hosted Paris Hilton spearheading a digital artwork fund by LACMA supporting women artists last year.

MARPLE: Yeah, totally. The other thing about this show is that I really wanted it to have a feminist umbrella, and besides just having feminist artists in the show, which is one way of doing that, I wanted to tell this story about artists from different generations who’ve influenced each other in a very non-linear and intuitive way.

DOLLE: So, who are you considering feminist artists in Interreality? Even if they don’t proclaim themselves as such, I believe the work of Oona is triggering deep conversations on body politics and the perception of women in society.

MARPLE: Alida Sun, I would say for sure. Connie Bakshi. I would say I'm a feminist artist. Jen Stark, Aya, Mark Flood, Cindy Phoenix identifies as a feminist artist. Ellie Pritz, of course, and Lindsey Price. Christine Wang, obviously. Aureia Harvey. I would say almost all of them.

DOLLE: What about Claudia Hart?

MARPLE: Oh, yeah, of course, Claudia Hart!

DOLLE: I love that it has this underlying statement, a feminist show in disguise.

MARPLE: I wanted it to be a feminist show, but I didn't want to do a show that's just women and non-binary artists. I did that already at Vellum LA when I co-curated Artists Who Code. I wanted to do a show that's just more inclusive.

DOLLE: How did you bring all these artists together? From a curatorial standpoint, I work with artists I feel close to, their aesthetics and the conversation they engage with. It seems that you were also looking for a sort of balance.

MARPLE: I worked closely with Steve Sacks of bitforms gallery and Aubrie Wienholt of PR for Artists, who produced the show together. They brought a lot of artists they knew to the curatorial table. Even Savannah who works for Aubrie recommended a lot of artists that I ended up including. But yeah, I wanted there to be as many traditional artists as digital artists, as many women and/or non-binary artists as men. I wanted to pair artists with big social media followings like Jen Stark or Parker Day with artists that aren’t as well known. I wanted artists that were more established with more emerging artists. Abstraction with figuration. Slick with punk. Dry with wet and juicy. I feel like that's the main concept of the show: just a kind of harmony of modalities where nothing is super dominant over anything else.

DOLLE: What about embodied experience? You are showing artists engaged with new technologies and with a sensibility of the physical space but we're also looking at screens. So how do you put this together as experiential?

MARPLE: I would go to NFT shows and I would see all this work on the same size screen, the same orientation at the same height, and it would just homogenize the work. And then I would go to traditional art world shows, and there'd just be paintings. Just hung on the wall, and I would be like, does this really reflect reality? Is this really talking about the world I live in today? Because it doesn't feel like it. I think art's job is to be a sort of mirror to the world we live in so that we can have critical discussions about it. And then, having come from Night Gallery and putting on like a hundred shows and having worked with amazing artists like Samara Golden, who really knows how to create an experience in space, I wanted to put on a show where the installation was an art piece in and of itself.

DOLLE: I love that.

MARPLE: The show itself is an artwork. And then, there's artworks inside that larger artwork.

Mieke Marple, Dn't Ask Why, 2023, courtesy of the artist, bitforms gallery, and PR for Artists. Image by Joshua White

DOLLE: It’s so important to be creative with the physical space when exhibiting digital works. I feel particularly NFT galleries need to be less linear and more creative with their presentation and aesthetics. Looking at screens in a white wall gallery space isn’t at all mesmerizing.

MARPLE: Just to explain that further, when I say the show itself is an artwork I mean that I want there to be something magical and seductive about every part of it. And also for every part of it to have a critical underpinning. For example, we used metal studs to create see-through walls and it's almost impossible to look at one work by itself. Whenever you're looking at a work, you're also looking through the wall and seeing the back of another work and some other works just feet away. It's emphasizing just how connected we are; how all the works are.

DOLLE: It sounds like a collage when we speak about it like that!

MARPLE: Yeah, it's almost like a collage in a space made of multiple artworks. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts, right? These artworks are almost literally overlapping each other in space and creating surprising moments and connections, and that’s really exciting.

DOLLE: Are all the pieces for sale?

MARPLE: Oh, yes. (laughs) It's a selling show. But you know, it is interesting that my partner, after he saw the show, he told me that it really felt like a biennial, which I thought was interesting. Maybe that's just the scale, but I think there's more to it than that. What’s interesting about survey shows is the concept is usually very, very broad if there is one, but basically it's just a kind of temperature taking. What kind of art are people making right now? And, I think that's what this show is too. It's taking the temperature of the art landscape … and not just in LA. There are some artists in New York, Chicago, Miami, in London, in Berlin, Shanghai, Mexico City, and Rome. So, it's pretty international.

DOLLE: What was the audience’s response? Was it a super LA scene? A more digital art scene? Any noticeable criticisms from the traditional art world?

MARPLE: At the opening, I would say there was more people from the digital art world than the traditional art world, which is definitely something that I want to change because I feel like the traditional art world is who could benefit most from exposure to this show. The other thing I noticed was, like, a lot of the work is more interactive. My pieces have AR. So does Lindsey Price’s, and you have to scan a QR code and use your phone to activate it. OONA’s was participatory. Alida Sun’s had a live digital sensor. So, there was a lot of participatory work, which goes hand in hand with the Web3 ethos, you know, where the line between artist and collector can get blurry, and co-creating is a very popular idea.

DOLLE: Artists and collectors are more hand in hand in web3, indeed. I have recently collected more works in web3 than in contemporary arts.

MARPLE: Right, but I noticed that a lot of people were hesitant. There wasn't as much participation as I hoped. I was talking to Alida Sun after the opening and I just realized that people are so trained to have this passive relationship to art.

So many people expect art to behave like a painting, right? It hangs there. You sort of appreciate it and then you move on. There's not a lot of interaction, or co-creation, or anything. I just realized there has to be a lot more education around this, that art is more than paintings, and an audience’s relationship to art can be more than just a passive one. Alida reminded me that this is a movement, you know. It’s bigger than me or this show.

DOLLE: Yes, the human impulse. You understand the collector's psychology and its attachment to the uniqueness of non fungibility. With NFTs, digital art could finally have the same one-of-a-kindness as a painting. What about traditional art collectors?

MARPLE: I think a lot of traditional art collectors are intimidated or wary of collecting digital art. I wanted to take away some of the intimidation factor by showing all the different kinds of work seamlessly side by side. I wanted to show where there was something for everybody. Like, maybe you would come in as a painting lover, but you would leave having seen your first painting with AR or digital work made with AI and that would expand your ideas about art.

Auriea Harvey, Gray Matter III, 2023, courtesy of the artist, bitforms gallery, and PR for Artists. Image by Joshua White

Interreality, curated by Mieke Marple, is on view through November 25 @ The Desmond Tower 5500 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles with a special performance event, today, November 18 from 6-9 pm.