interview by Karly Quadros

Fuck art, let’s dance.

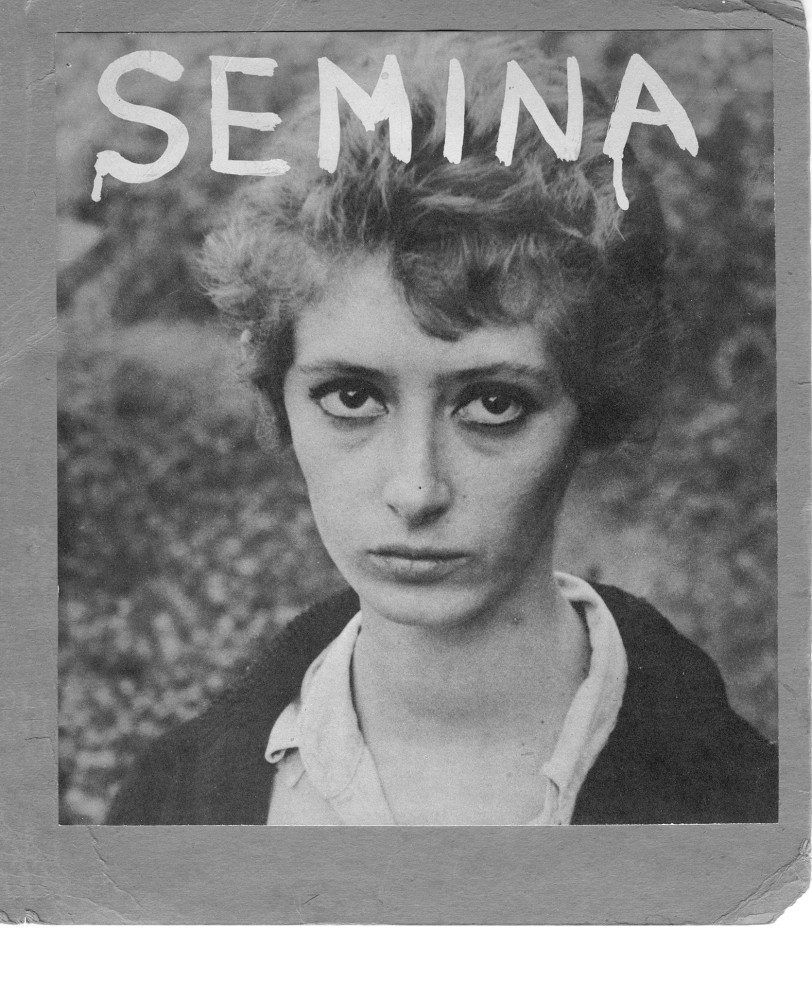

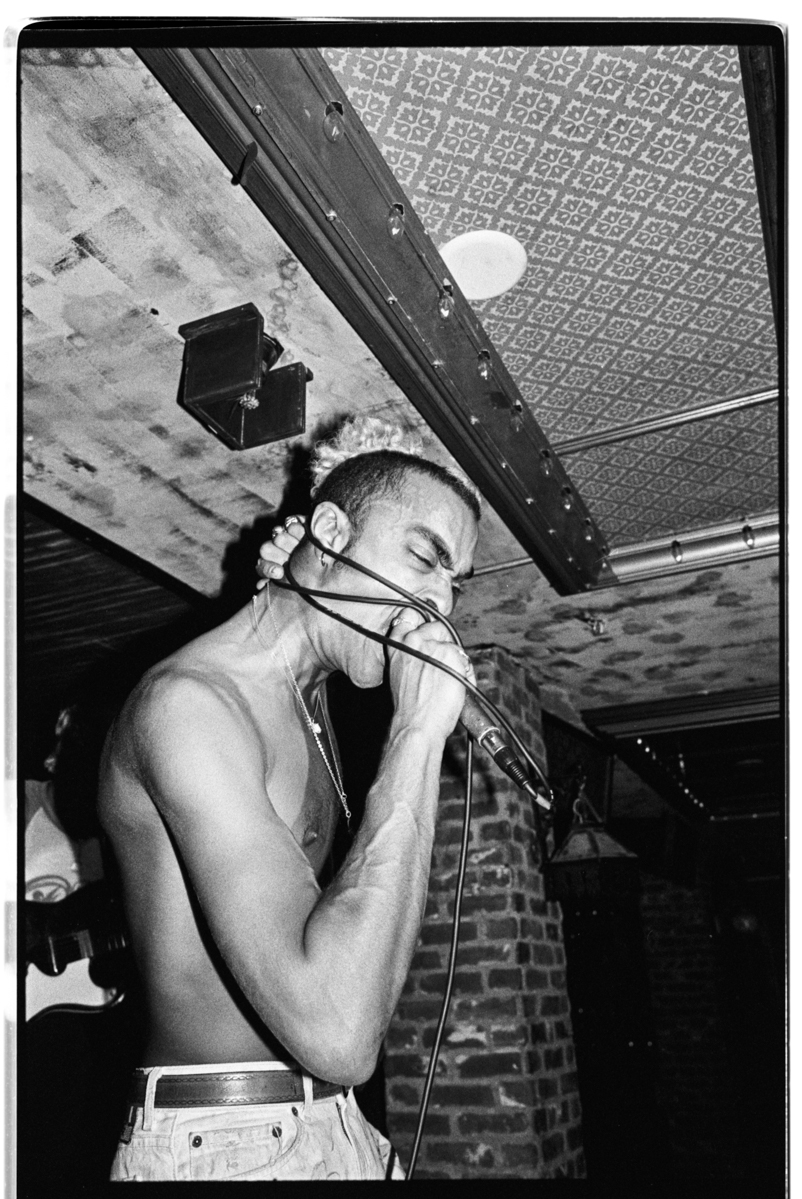

It’s the attitude that Colette Lumiere had become known for, immortalized in a mural that she painted on the wall of iconic ’70s downtown New York nightclub and art scene haunt Danceteria. She’s celebrated for her bold personas and expansive multimedia projects from street art to installations to fashion collaborations, yet her later evolutions have received less attention. A new show at Company Gallery, Everything She Touches Turns to Gold, running until March 1, explores the artist’s career in the ’80s as she ventured off to Berlin under the guise of a new persona, the mysterious Mata Hari and the Stolen Potatoes.

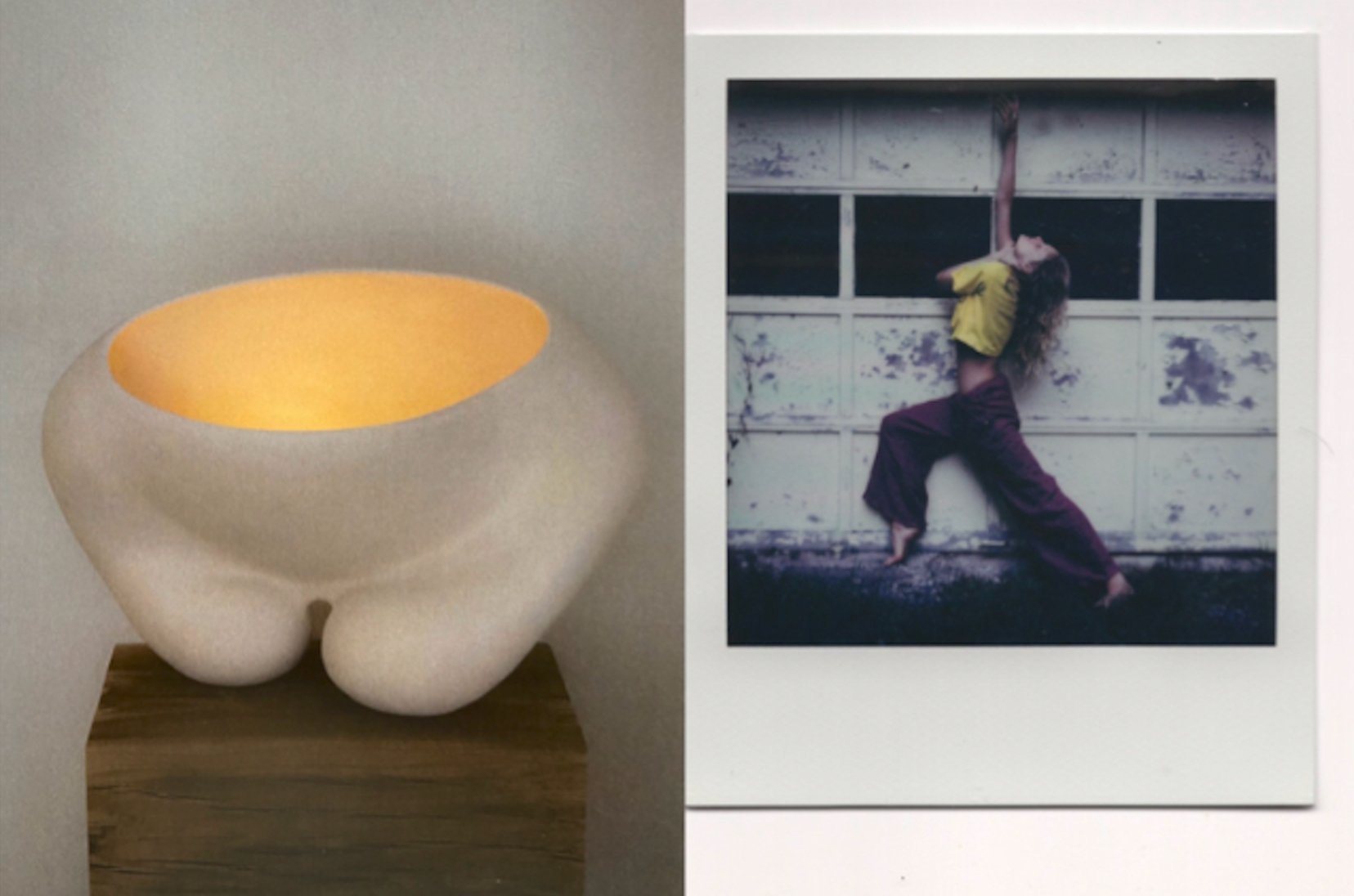

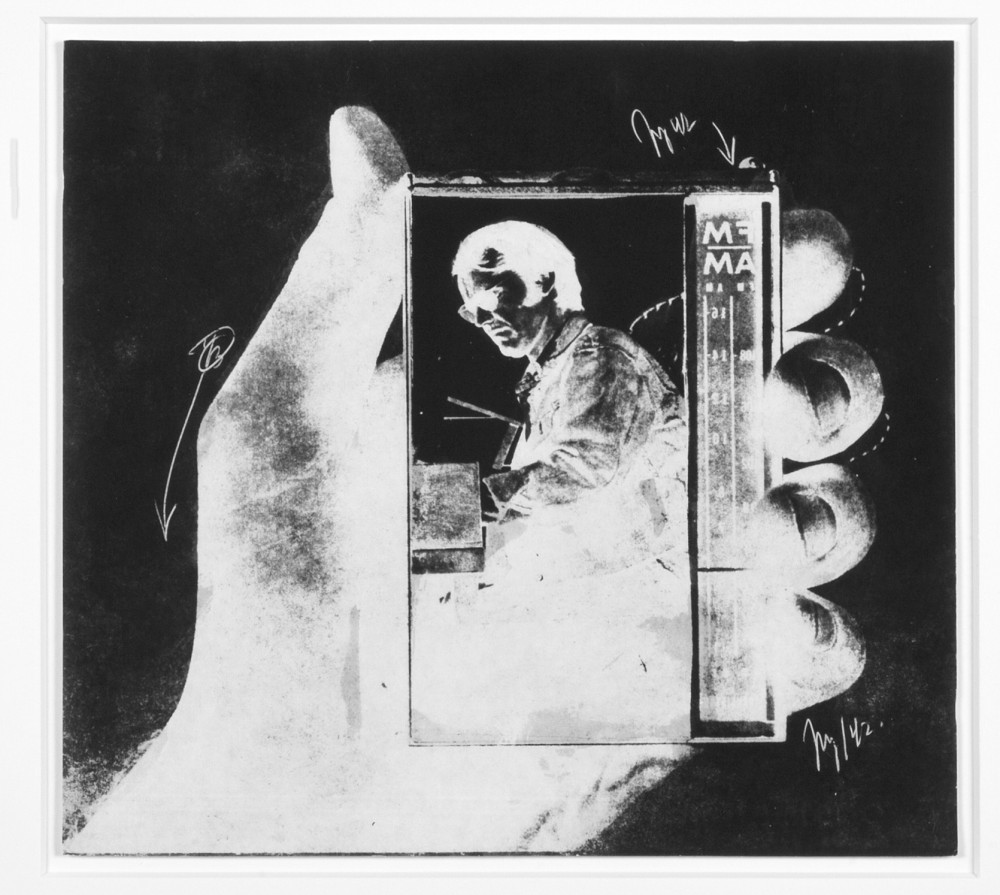

Lumiere always had a surprisingly contemporary attitude toward blurring the boundaries between the public and the private, between art and commerce. She began by painting cryptic sigils on the SoHo pavement at night and has shown art everywhere from the MoMA to Fiorucci shop windows to German nunneries to nightclubs. Her longest running piece was a 24/7 installation in her own apartment, stuffed from floor to ceiling with champagne and blush-ruched fabrics, a polymorphous punk rock Versailles. Lumiere took that louche crinkling of fabric from her Living Environment and translated it into harlequin frocks that she wore like a uniform. Her influence reverberates widely from Vivienne Westwood and Madonna’s ragged, spunky takes on period clothing to the elaborately staged personas of Cindy Sherman and Nadia Lee Cohen.

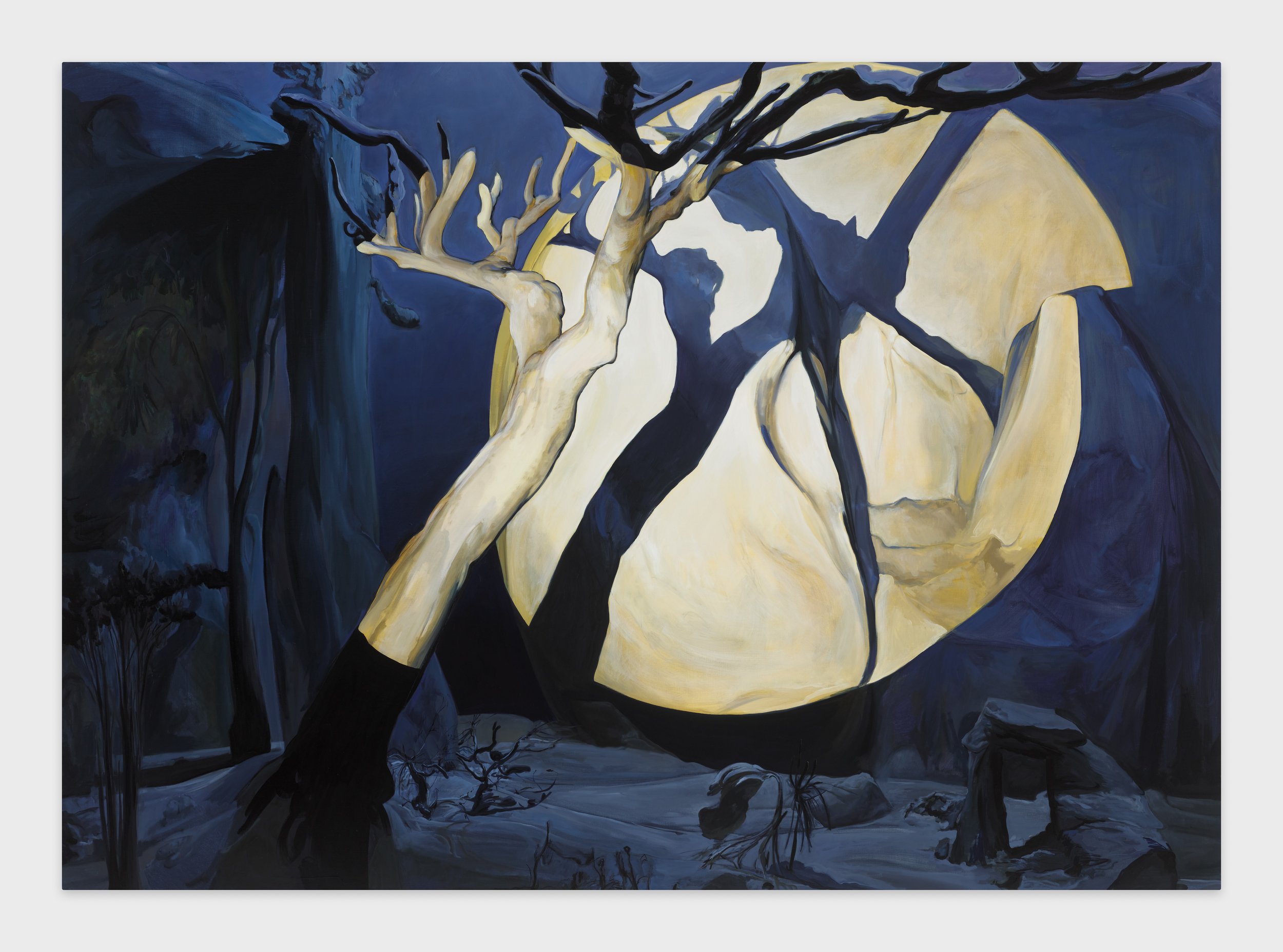

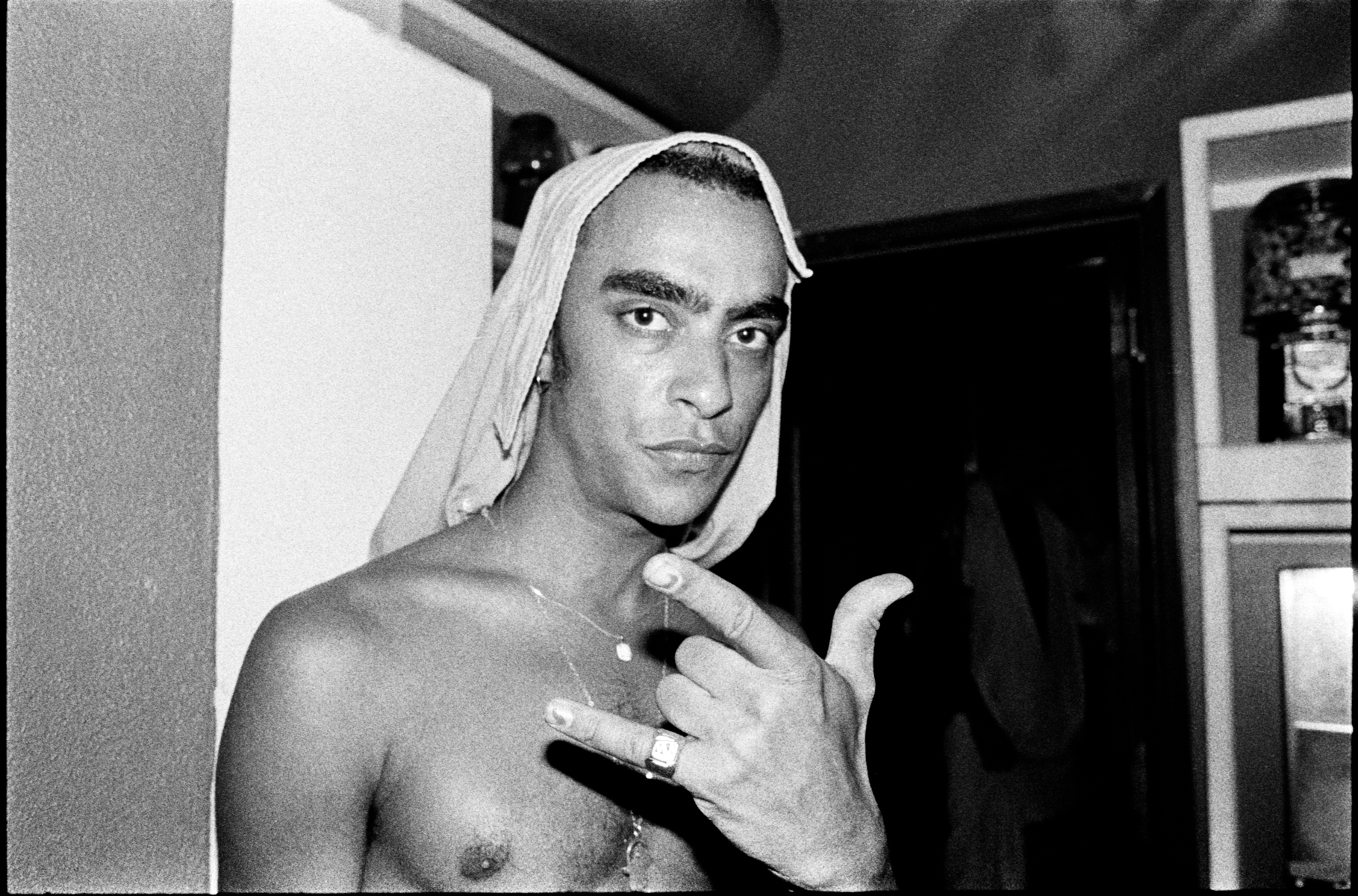

Growing frustrated with the limitations put on a young female artist, in 1978 Lumiere staged her own death in a performance at the Whitney Museum. She emerged a few days later at PS1 Contemporary Art Center, beginning an ongoing dynasty of artistic personas and eras. Everything She Touches Turns to Gold features the artist’s under-celebrated paintings, mostly from the early ’80s, “metaphysical portraits” exploring herself, her friends, and the subconscious. While her ’70s works recall historical reclining nudes including staged photos and durational performances in which she napped in poses modeled after classical paintings such as Manet’s Olympia. Her Berlin period, instead, foregrounded motion. The figures in her portraits wave. They evade. They drift and dream and run away.

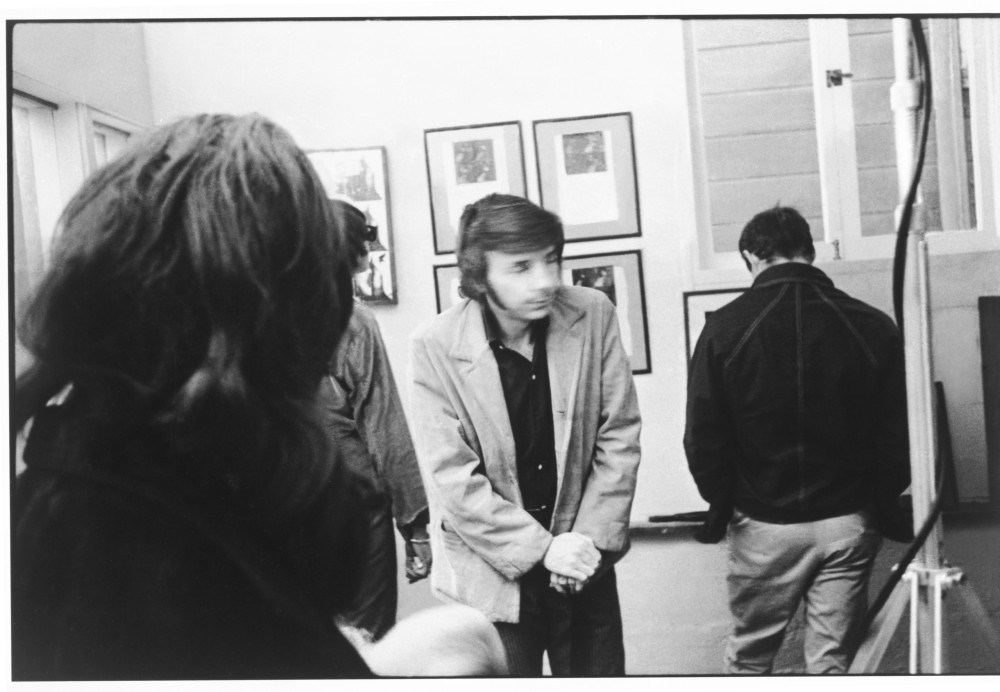

I recently met up with Lumiere at Company Gallery to explore the new collection. Now in her seventies, Lumiere is as true to herself as ever in a ruffled white blouse beneath a hot pink Victorian riding coat. Tunisian-born and French-raised, her accent is caught somewhere between her native French and a dry German lilt. We spoke about Berlin before the wall came down, resisting categorization, and, of course, potatoes.

KARLY QUADROS: I wanted to focus on the gallery show because it covers this specific period of time: Berlin in the ’80s. Rather than focusing on performances and living spaces, this one is much more concerned with visual art and paintings. A lot of what is written about you concerns a smaller period of time: a lot of your ’70s work, your show at the Whitney where you killed your first persona. But there's still several decades of artwork after that.

COLETTE LUMIERE: Interesting how people focus on one thing to describe you. They get set.

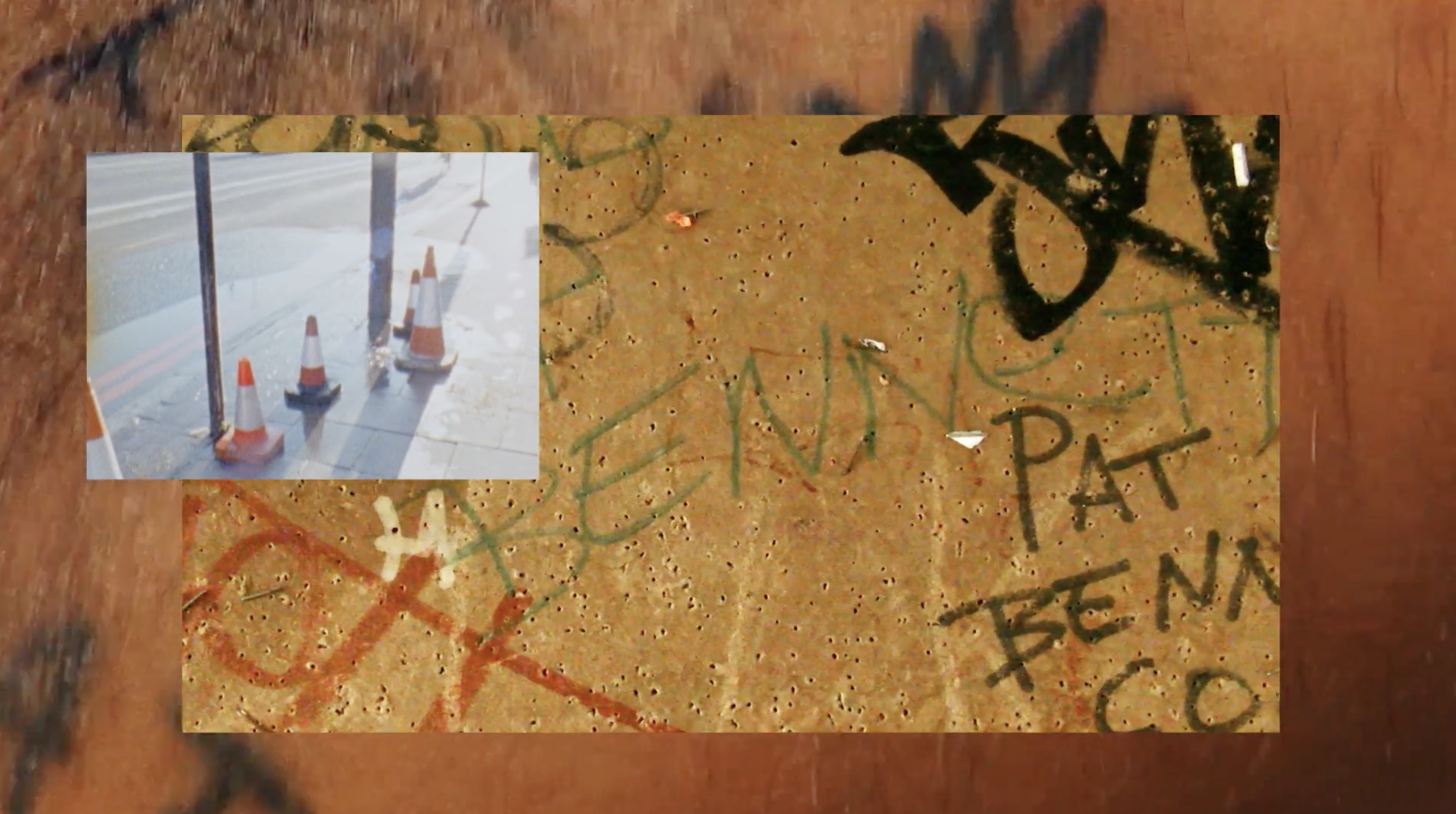

I really began as a painter. But it wasn't long before I got restless. It was in the air. I was very naïve, and I wasn't coming from Yale or whatever. I was coming from nowhere, actually. It was before street art became popular. There was a bar on Spring Street where I did a lot of my graffiti work. I always had an accomplice, a friend, a girlfriend or somebody helping me out, watching for the police

Simultaneously, I was creating the environments that I lived in. I got intrigued with using space in a different way. This was a time where art changed completely, and unconsciously, I was picking up on that.

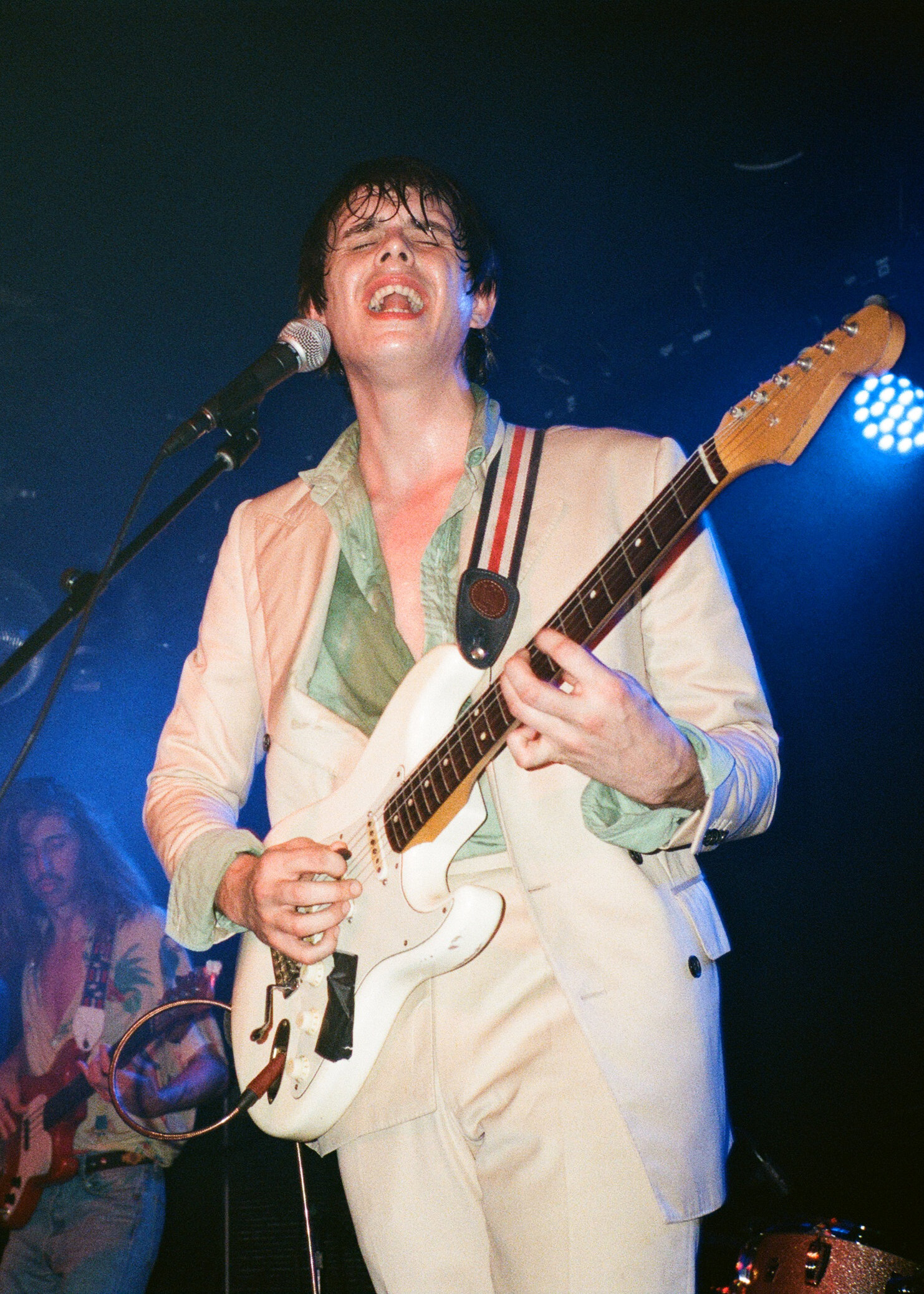

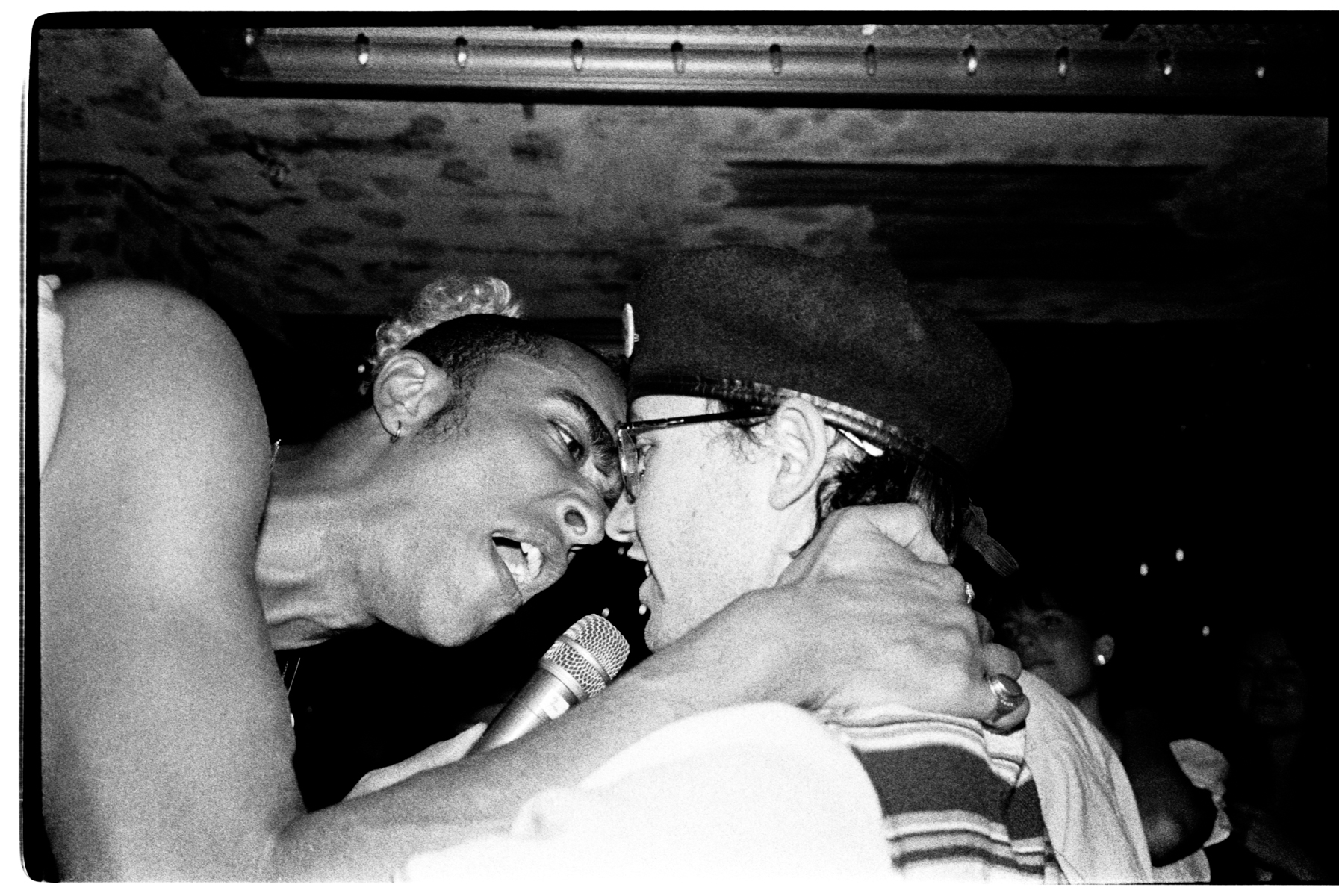

I used to go to the nightclubs. It was at Max's Kansas City. No place like it ever again.

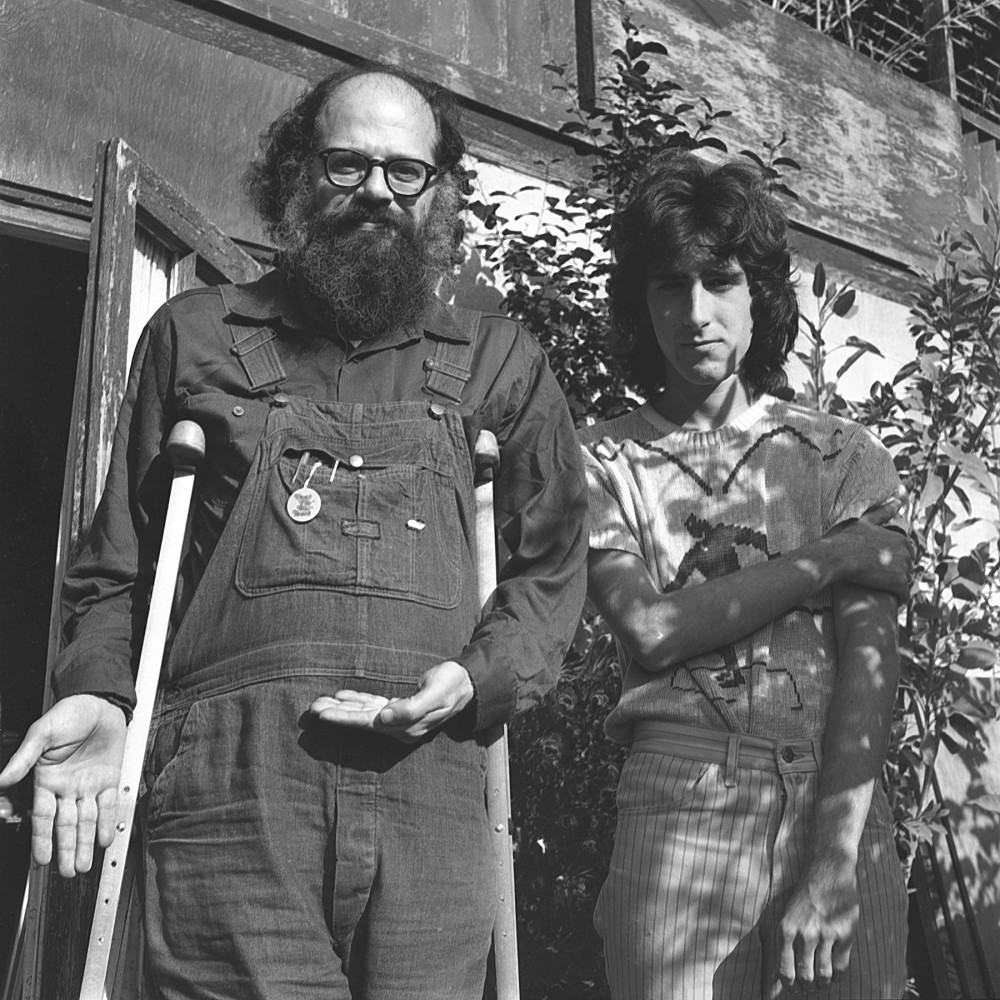

The people hanging out there were all famous artists. They were [Colette adopts a macho stance] men, and I was a young girl and I usually had another young girl with me. But one night I met [land artist Robert] Smithson, and we had a long conversation. I said I had learned about him and we were doing the same thing. I think he was rolling his eyes. He had other ideas in mind, but we took him to my place, which was near where he lived and he walked in my environment and then he sobered up. We gave him a cup of coffee, and we talked about art. And from then on, he introduced me to everyone. Richard Serra, Carl Andre. That was my beginning.

QUADROS: Why did you decide to go to Berlin?

LUMIERE: Sometimes I just like to give up. Surrender. You always want to plan your life, and then sometimes I find it's best to surrender.

So, I was really at that stage of my life, where my Living Environment had come to an end. I think I was ready to be dismantled. I lived in an artwork that was ongoing. It was very extreme, and I was part of that artwork. And there was another element, which was my landlord, who tried to throw me out from the beginning [laughs]. So it was coming to a climax. And then I get this invitation to go to Berlin. How convenient!

I don't know why I'm talking about my past again. This is really a problem I've noticed. But this show is Mata Hari. We're talking the ’80s! Berlin was a new beginning.

QUADROS: Who is Mata Hari the persona?

LUMIERE: Actually, I didn't know at all about Mata Hari the person when I chose that name. The reason I chose Mata Hari was because I knew she was a spy… You had this image. The Berlin Wall was not that far away.

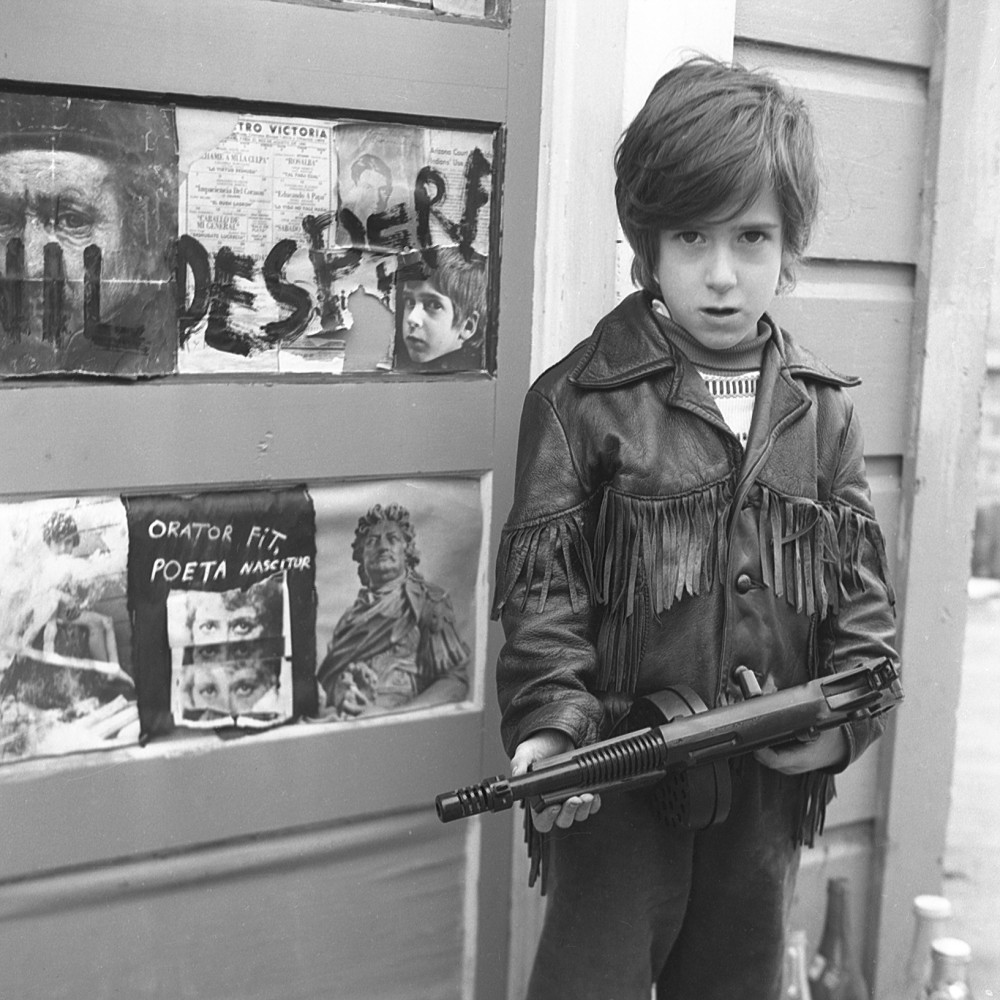

None of my personas are actually about the name. A lot of people think Olympia, it's Olympia from Manet, Justine, it's de Sade, but none of them are. Of course Mata Hari has something to do with the name, but I had to make something new out of her. So, it became Mata Hari and the Stolen Potatoes. It was the potatoes because it was the food for Germany. Then stolen made it more mysterious, dangerous. That's what I felt Berlin would be like. I would take pictures of myself, running like somebody was going to catch me, like the police or the Gestapo.

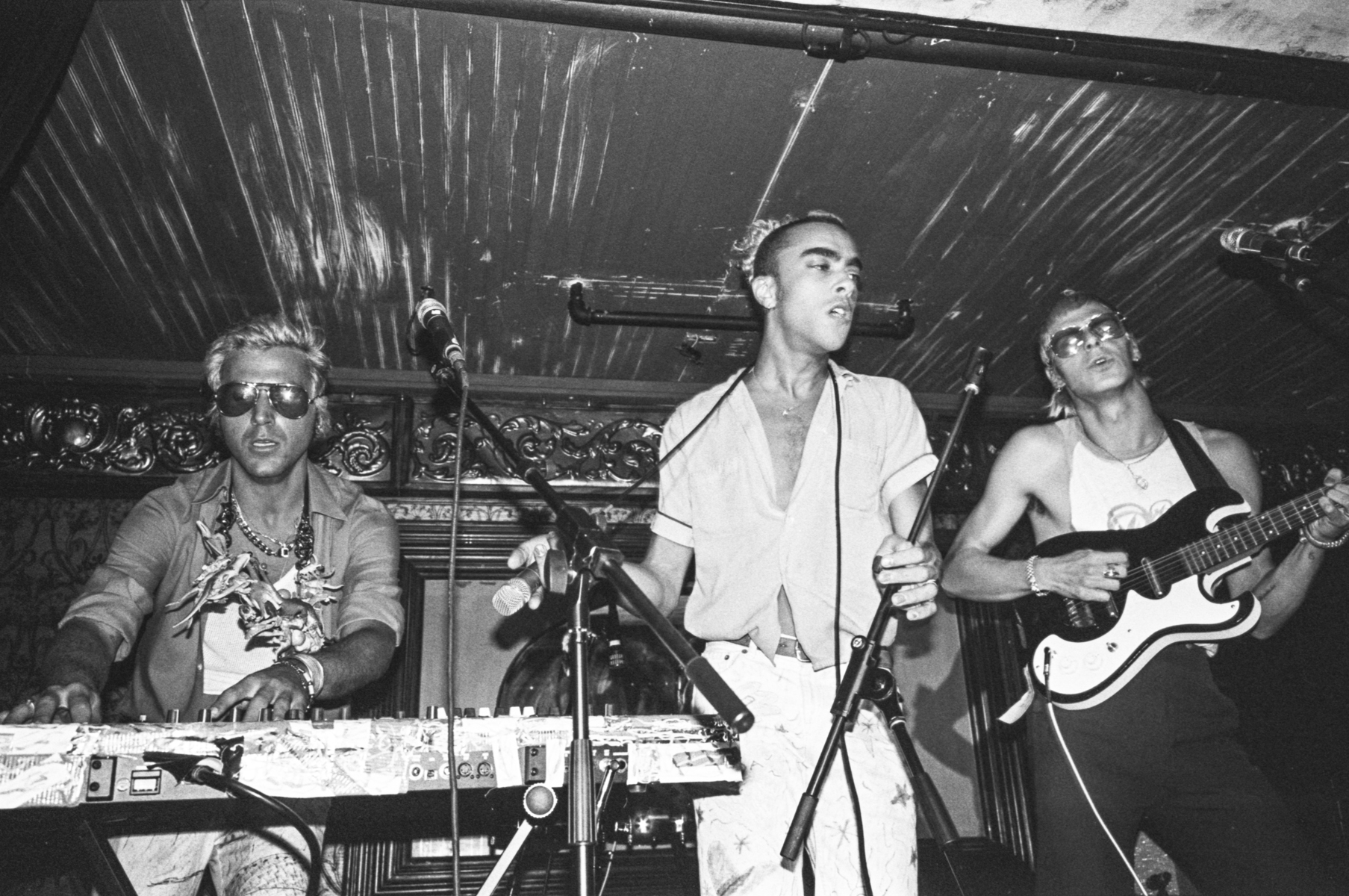

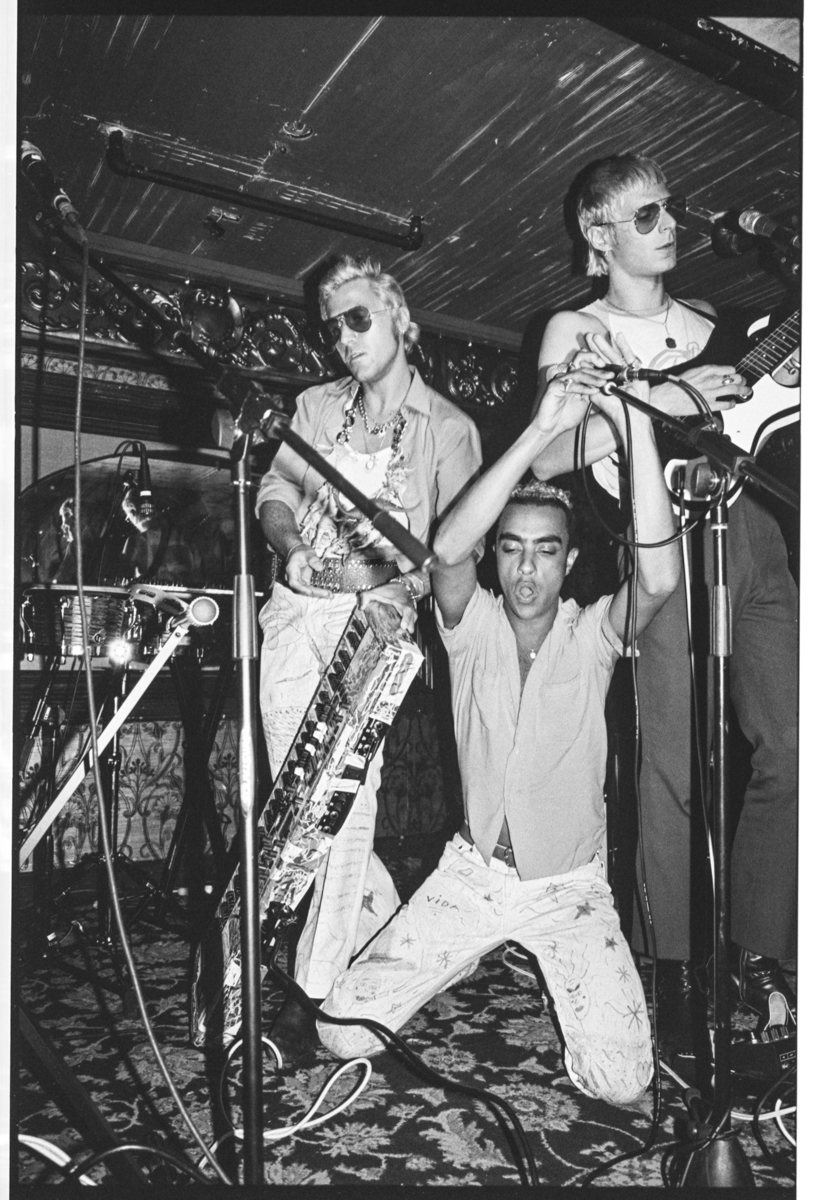

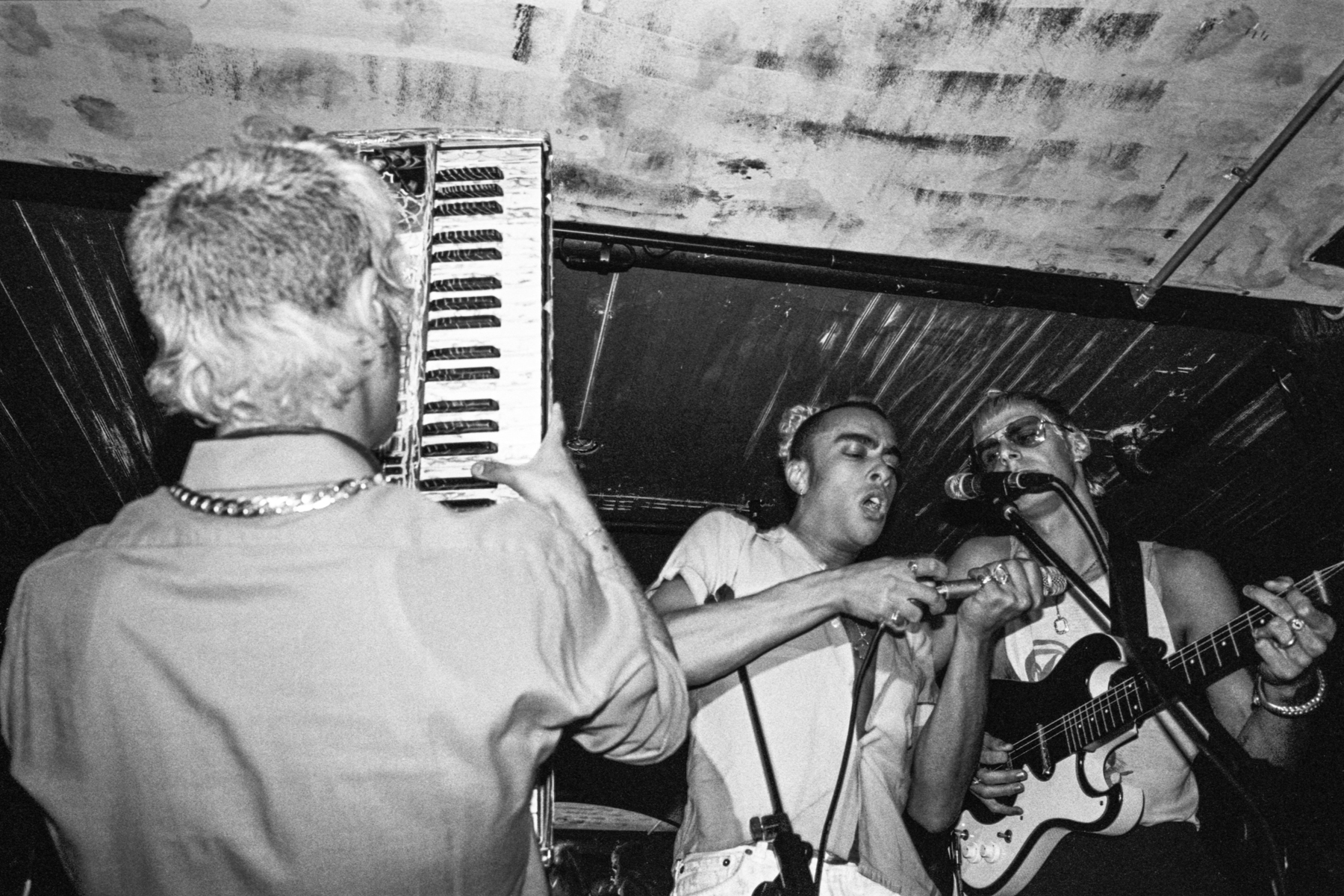

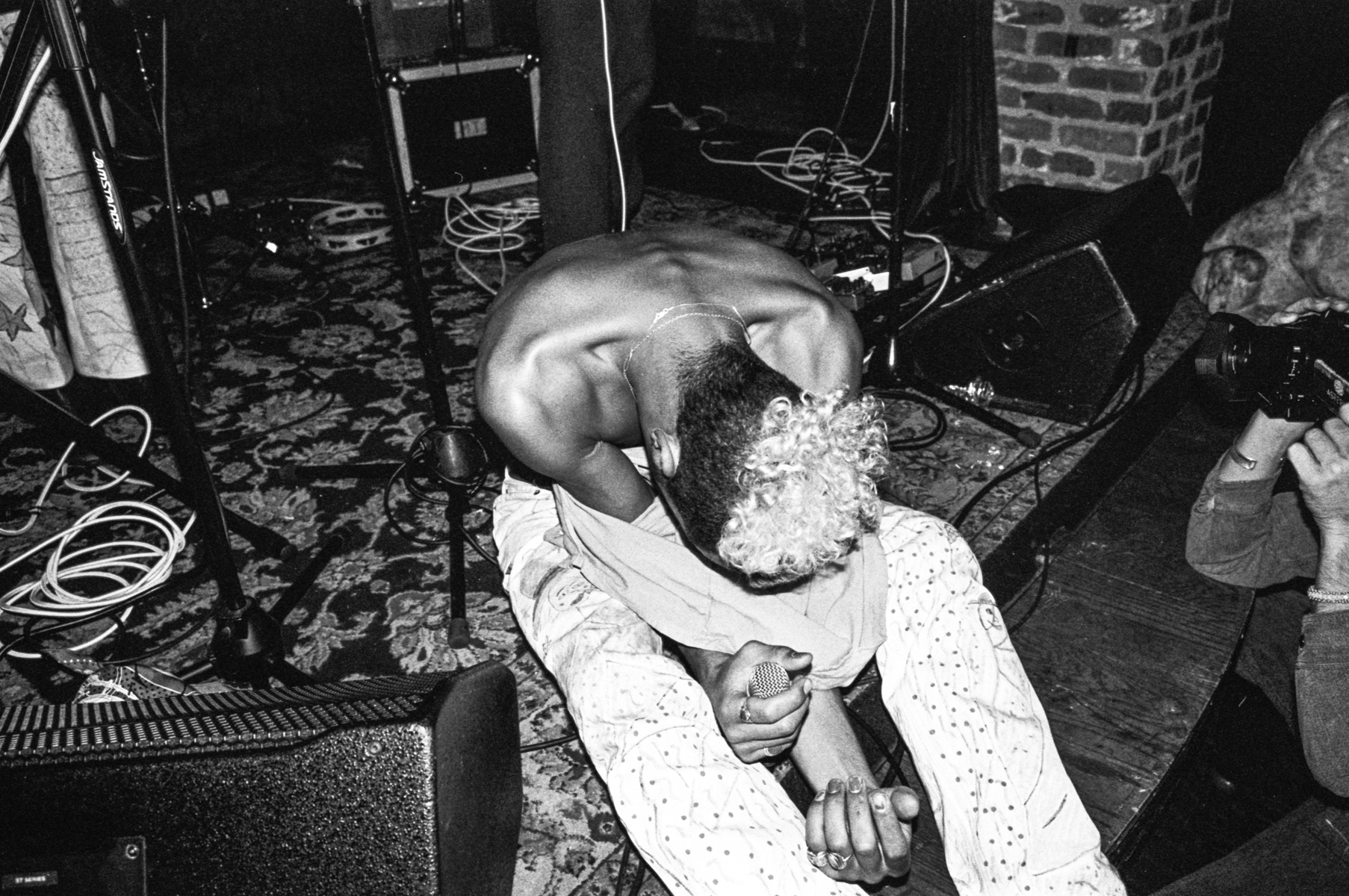

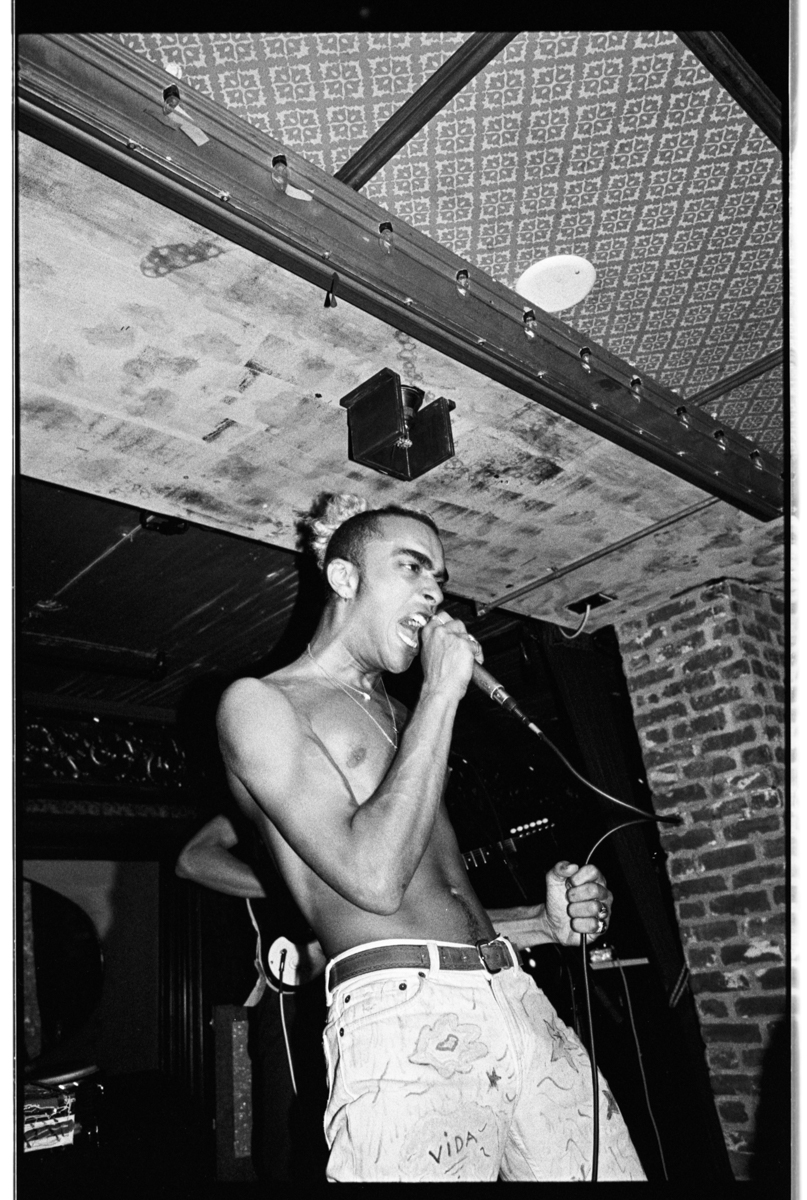

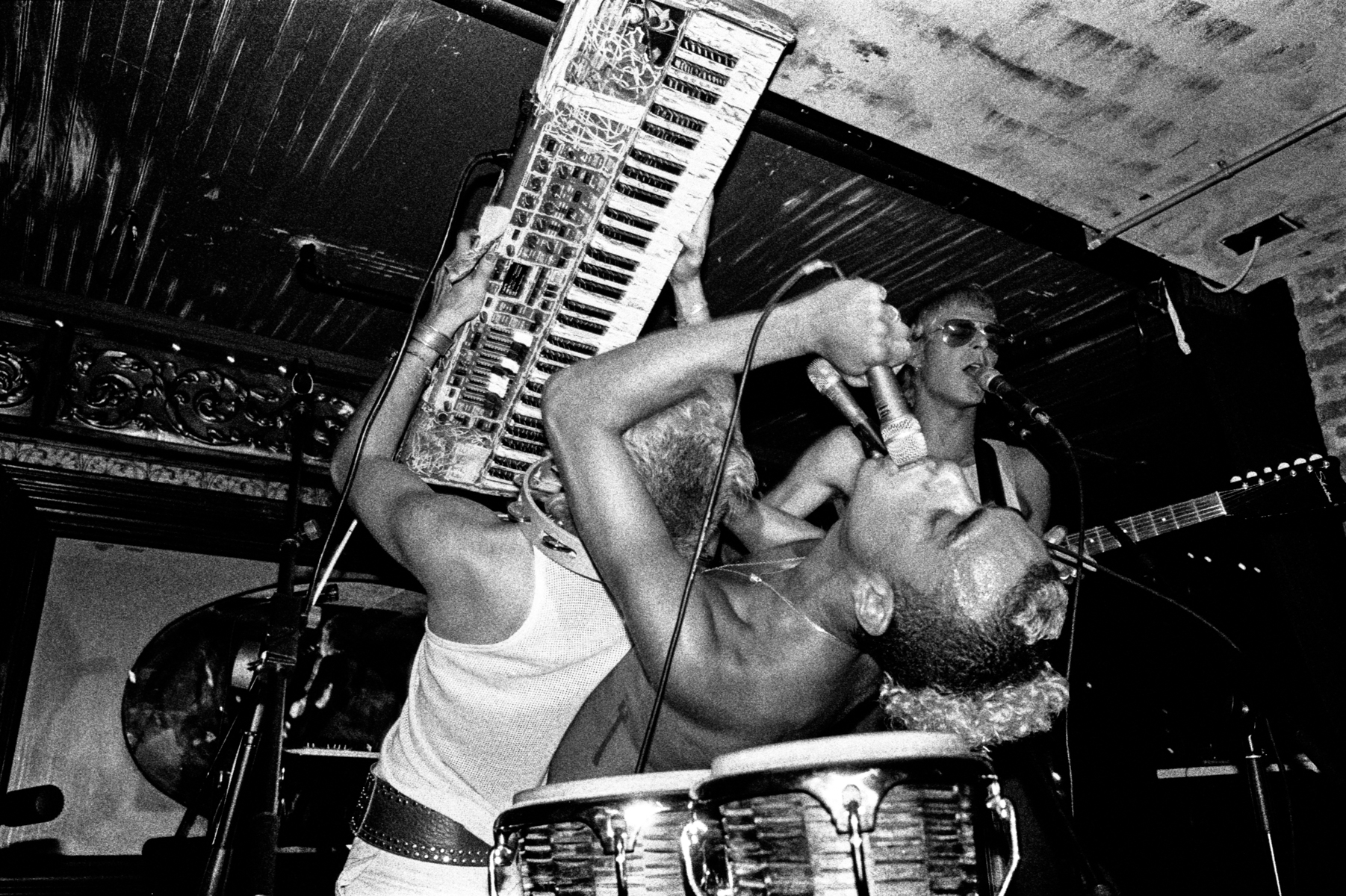

I got into [the show’s videos] because it's really old footage. One of them was staged at the opera where I did a music video that was interrupted by the police. I have a tendency to do things I should not do for the sake of art, of course, because I'm obsessed. I had the approval of the director who I had done sets and costumes for at the Berlin Opera.

We were just starting to rehearse. It was a potato song, which is in the show as well. It was called, “Did You Eat?” Well, apparently that was not legal. And everybody came out from the kitchen, from the offices. “What is going on here?” And here I am doing my music video rehearsing. We were just at the beginning, and the police came. And I said, “You're not gonna stop this.” I said to everybody working with the band, “Let's just go. Let's just finish it.” At the end, my wig is like half down. People don't know this when they see the video.

QUADROS: What was the Berlin art community like?

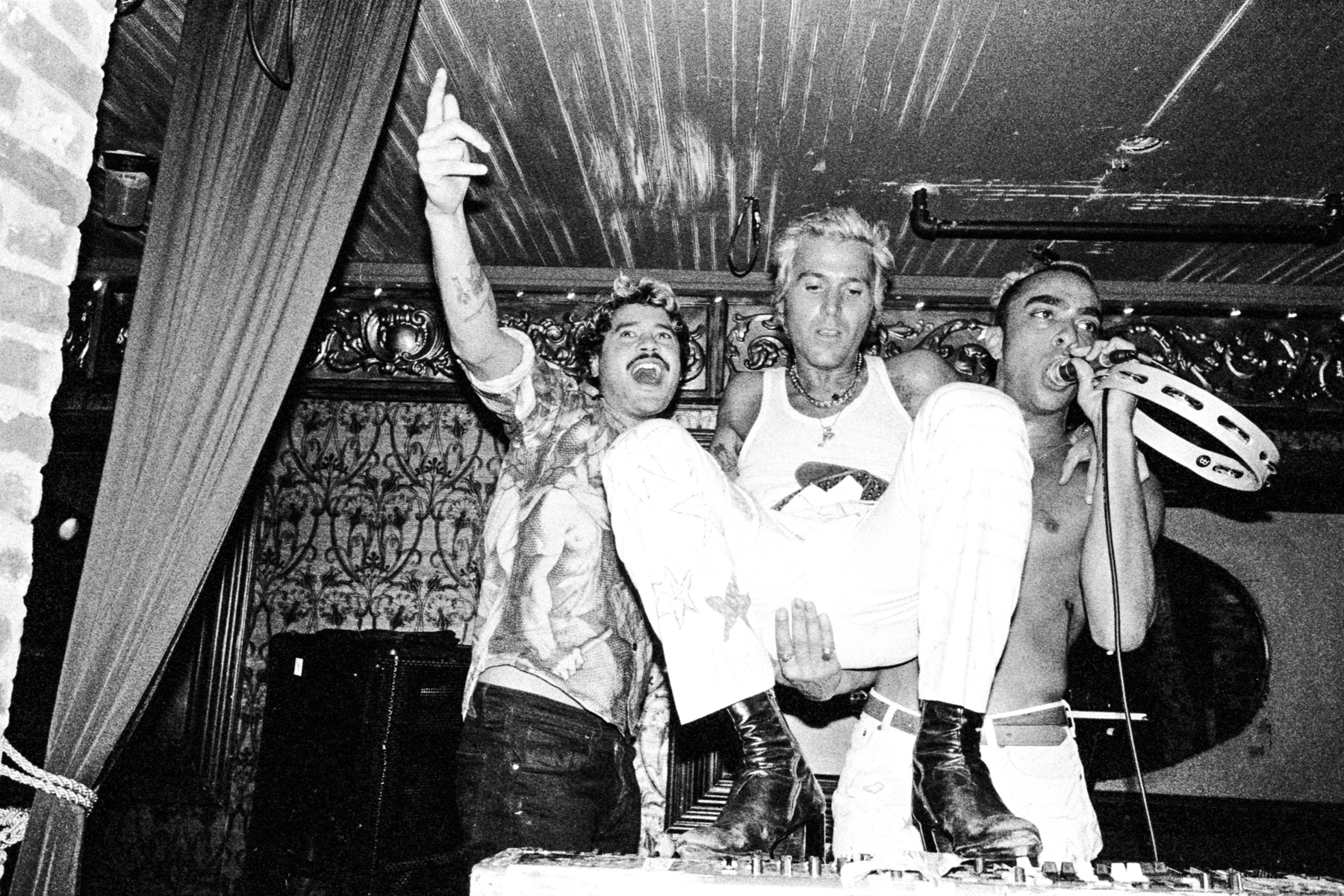

LUMIERE: At the beginning there was a lot of resistance for me, and there usually is. I've noticed this everywhere I go. First of all, I'm a foreigner. And number two, it was the height of the wild painters, the Berlin guys – Lüpertz and Rainer Fetting. It was a whole crew of them. They were very macho, and they ruled the scene. They were very serious, and they drank a lot, and they were very depressed. And here I am, bringing my art to a nightclub. I took a boyfriend's Volkswagen and I painted it and put the potatoes in. I arrived in the Volkswagen, and I did an installation in the nightclub they all went to. It was called, There's a New Girl in Town.

This German art magazine came out with a story that art in the nightclubs is what's happening. In New York, there was Palladium. It was where all the big artists like Schnabel, Clemente, Keith Haring, Basquiat, and Colette [went], but Colette was on her own always. So, it explained how I kind of started that way back before in Danceteria. Then they were respectful. Then I won them over, and they were nice to me.

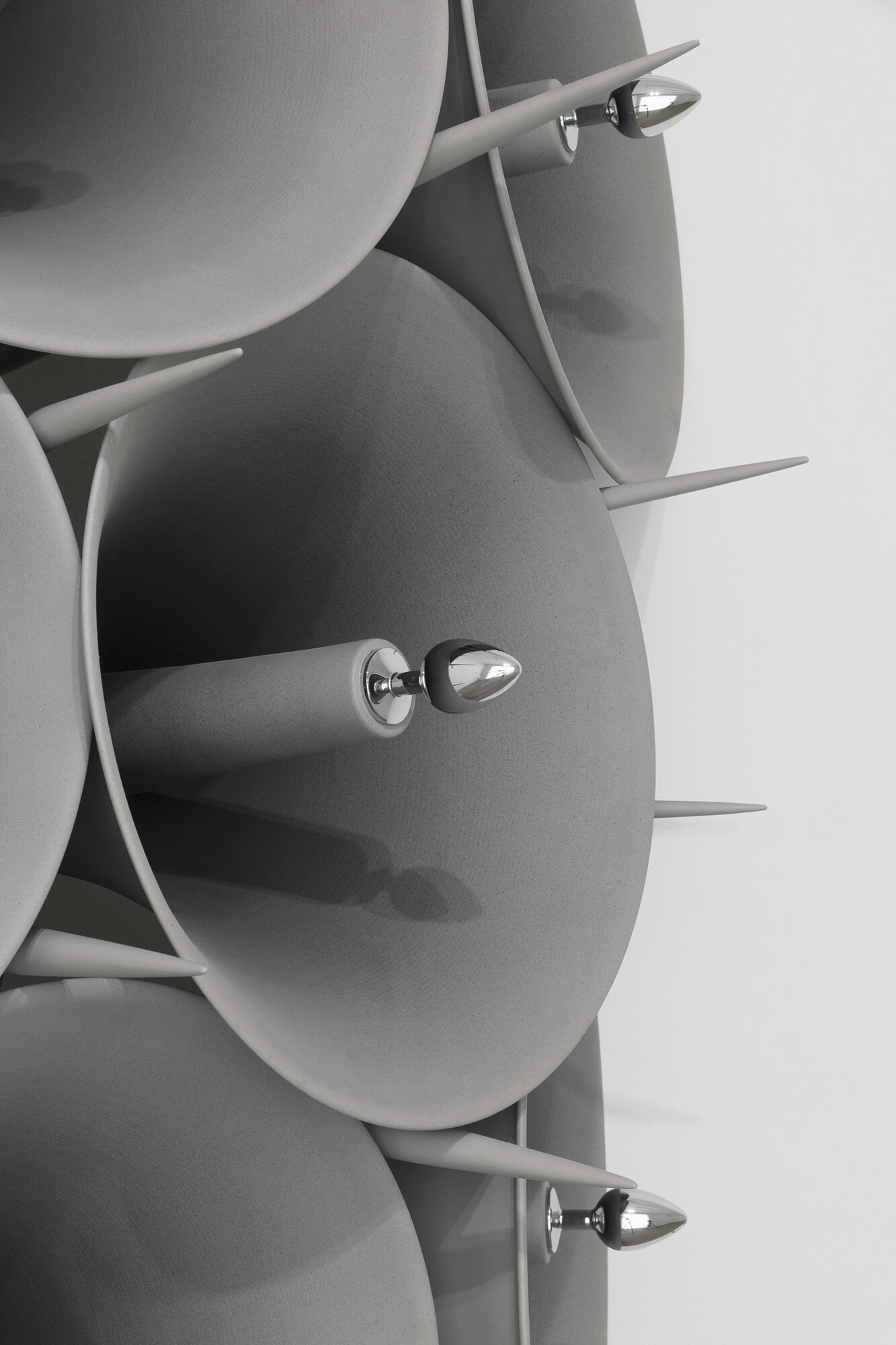

QUADROS: Can you speak a little about the Silk to Marble series? Many things come up for me: the seductress, a statue of Venus, a nun, decommissioned artwork covered in a sheet, perhaps even a dead body covered in a sheet.

LUMIERE: Well, you just described it. It's not that I'm against high tech or having a big budget, but usually I don't have either available. So I'm very good at transforming material. It was an evening at home bored and I'm leaving, [so I said] “Let's make some art!” I had this one sheet. It was very organic. Organic is a big word in my work.

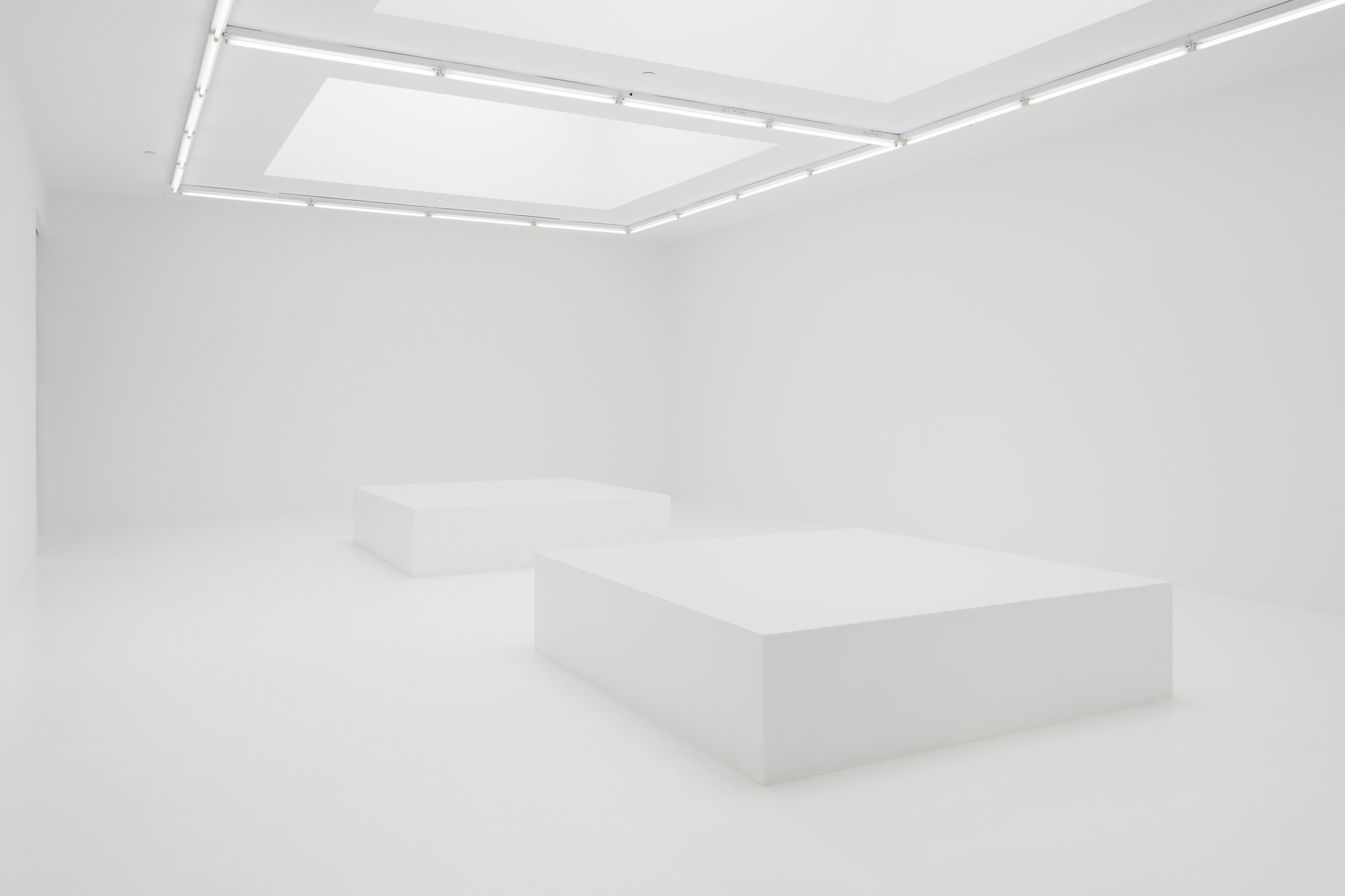

They were first exhibited in Berlin, in the house, Kunstlerhaus Bethanien, which was beautiful because it was a nunnery, so it had these oval religious arches, white walls. It was perfect for the series. And then out of nowhere at the opening, I appeared behind one of the columns way up – the ceilings were unbelievably high – and there was special music composed for that performance.

QUADROS: A lot of your performance work is inspired by art history and the canon, often subverting or playing with classical images. But these “metaphysical portraits” seem to come from somewhere else entirely. What can the world of dreaming offer us?

LUMIERE: My art was trying to reach the invisible, the unknown. That's what I'm reaching out for… I don't care what the trend is… I don't like trends because trends are things that happen and leave, and I'm interested in the eternal. Artists – I guess they’re called visionaries – they follow that line, and they're mystical in a way. I try to stay away from describing myself as that, but that's what interested me from the beginning: the metaphysics, magic, the mystery of life and art. I'm always seeking for another dimension. That's what my soul is looking for, and whatever way I can manifest it, whether it's canvas or performance, that's my goal.

The feminine influence is a big thing too. Now it's much easier for women, but at the time I was doing it, my work was labeled feminine, like it was an insult. Even the women were insulted by me. Like I was an insult. Because I impressed my femininity in my paintings and the way I dressed. I always have fun anyway. That's another thing. Fun is very important.

QUADROS: You like to build the whole world. It can't just stay in the gallery. It has to be in the streets, and in the club, and in the bedroom.

LUMIERE: In the bedroom, yes!

QUADROS: Were you part of the punks?

LUMIERE: Oh yeah, of course. But I also wasn’t. I was never a part of anything is what I’m trying to tell you. In the clubs it was so cool to be mean! [Colette adopts a snarl and a tough pose.] I like punk, but I don’t like it when it goes in a very negative direction. So I created my own thing, which was a contradiction. I added the Victorian look, the soft look, and mixed it up with the tough look because it was only black, black, black.

QUADROS: It’s interesting because Victorian fashion is very confined and restricted, like a corset. But your clothing is much lighter and more playful.

LUMIERE: Well by 1980, I was getting restless to get rid of my Environment, but I wasn’t really ready. So, I started wearing it. It was an experiment in walking architecture. The whole idea was to use space in a different way.

I work very intuitively and later, I get what I meant, you know? I think intuition has its own intelligence. We live in a culture where intellect is so celebrated, not that that doesn’t have its role. For me, it’s always been about the unity of the mind, body, and the emotions. There’s a cerebral part of my work. There’s an emotional quality. I think this show reflects that.

QUADROS: Do you think you can explore something with painting that you can’t reach with performance or fashion or music?

LUMIERE: I love it and I don’t love it. I’m a loner, really. I like my private life. But it’s a contradiction because I also like to have large audiences and speak to lots of people. Painters are usually by themselves. With fashion and with music and with all of the other parts, I’d probably do a lot more, but I don’t want to because this is my first love. Being who I am and on my own time, that’s me.

QUADROS: I do think you were forward-thinking being so multidisciplinary. Nowadays, it’s so hard for people to make a living doing just one thing. So you see artists that collaborate with fashion designers or build window displays, all the things you used to do.

LUMIERE: I was always interested in pushing that line between art and commerce. And now it’s merged. And I don’t approve of that. But I pushed it.

QUADROS: Do you feel responsible for the people you’ve influenced?

LUMIERE: No, because in the end it’s not me. But it is interesting.

Everything She Touches Turns to Gold is on view through March 1 @ Company Gallery in New York City at 145 Elizabeth St.