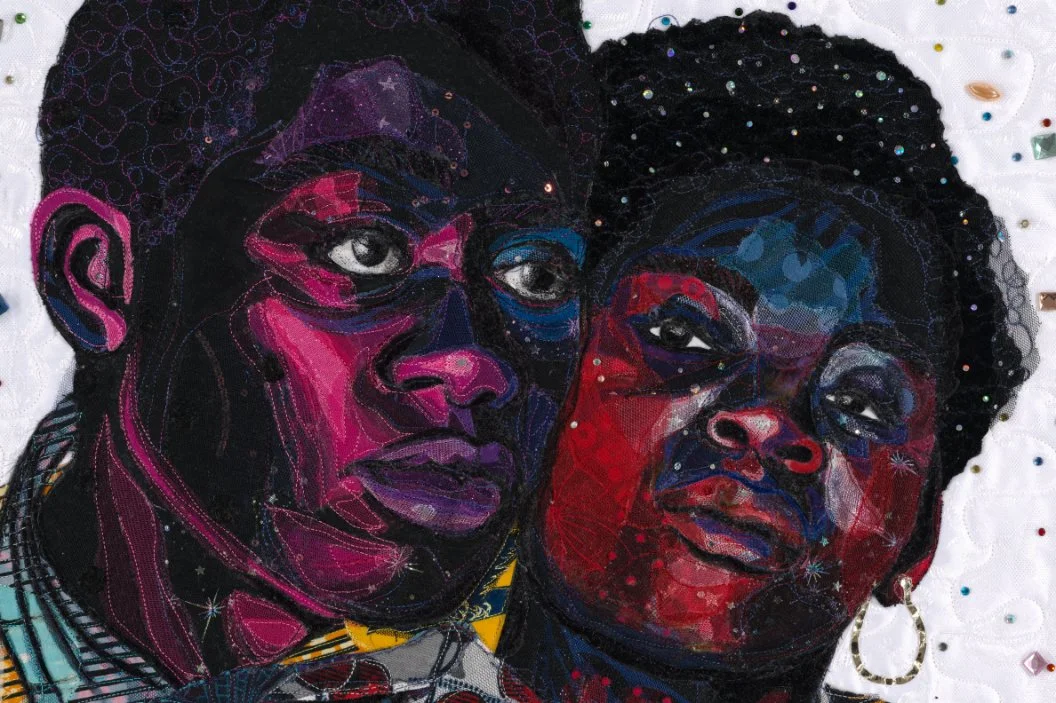

Bisa Butler

Les Amoureux du Kinshasa, 2025

After Amoureux Au Nightclub, 1951-1975 by Jean Depara

Cotton, silk, lace, sequins, netting, vinyl, glass rhinestones, plastic beads, and velvet, quilted and appliquéd

95 x 59 inches

Photo by Mark Woods. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch, New York and Los Angeles

text by Laila Reshad

Bisa Butler’s Hold Me Close at Jeffrey Deitch is a reflective meditation on forever, negotiating our allowances to seek closeness in one another in a polarizing and alienating landscape disfigured by reality, by today. Where reality warps our sense of relationality to time and place, it is such that Butler’s intricately woven and layered mosaics of memory, whether contrived or lived, speak to a far more precedented truth that is largely absent in works of the contemporary American canon. Butler’s work is truthful and radical, a headstrong resilience narrating the stories of each person stitched into memory. In each depicted face, whether solemn, or overjoyed, we are pulled into their complex and vivid worlds. The works are full of life and detail, and I contemplate how they can be so easy on the eyes and yet distinctly subversive. Layers of tinted fabric composite countless pieces into faces, projecting color onto each world the characters inhabit. Intricate embroidery overlays each face, elevating the cosmic feeling that comes about when viewing the pieces in stillness for a while. The images that form begin to take shape and breathe–we really stand before the people we look upon, peering into their inner worlds and the intimate moments they exchange among each other, between us and them.

Butler’s journey was more complicated, having come into the medium as a young art student. She explains, “Professionally, I made my first quilt when I studied art at Howard in my B.F.A., but I was a painting major. I really didn’t have the license to go canvas-free until I took a fibers class at Montclair State, of which the whole entire fibers curriculum was probably initiated in the ’70s by white women, feminist professors who pushed that all art students at Montclair State had to not just have the regular foundations–which was drawing, painting, sculpture, design–but they also pushed that you had to have fibers and jewelry making. Thank goodness they did that because I was the beneficiary of it.” From there, Butler took on what came naturally to her and so continued her lifelong dedication to experimentation, to pushing herself across mediums, to endless possibilities. When I ask if she still considers herself a painter, she says, “I feel your creativity ends with you when you stop living. So whatever I put my mind to, I am. Right now, I’m doing fiber, and maybe I’ll do that forever, but maybe not. I’m starting to wander into sculpture, thinking about soft sculpture. Before I’m working, I’m sketching. I’m still designing clothing. I’ve been making purses lately. I remember seeing Jean-Michel Basquiat’s grave, which just reads ‘artist.’ I think ‘artist’ is good, it covers all the bases. I feel like my talent has always been limitless.”

Bisa Butler

Hold Me Close (My Starship), 2025

After Untitled, 1974 by Steve Edson

Cotton, silk, lace, sequins, netting, vinyl, faux fur, and velvet, quilted and appliquéd

90.5 x 54 inches

Photo by Mark Woods. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch, New York and Los Angeles

There’s a genealogical nature to quilting, particularly in its ties to Black history both domestically and abroad, that communicates family history, positionality, class, background, ethnic origin, and cultural practices. Butler’s work is inventive and rooted in a knowledge of the history that shapes and informs her work, even though she doesn’t have a direct familial tie to a quilting ancestry–she takes shape and fills a void to synthesize the two sectors of culture she negotiates between, both Black American history and African history. The matrons of quilting have certainly informed her work from a critical perspective, explains Butler, “I went to the Whitney and I see all these quilts on the wall by African-American women, specifically the quilters of Gee’s Bend, which had last names like that of the Pettways. I thought these women were wealthy. I thought each one in the show was a famous artist. You have a show at the Whitney. You have to be making money. I was walking around the room thinking, I got it. I know what I'm going to do now. I’m going to be a fine art quilter just like them.”

Butler not only calls on the women of Gee’s Bend, whose work solidified her aspirations of becoming a quilter, but also the women of Ghana who use varied patterns in their quilting practices to signify fertility, wealth, class, and obscured ruminations on marriage and family, among many other things. So many messages are implicit and visible in her work, but the most engaging component is the various ways in which she subtly reinforces the narrative of the quilts. She establishes a legacy in her lineage, pushing forward what it means to shape and colorize fragmented or disregarded memories that matter. Saidiya Hartman conceptualizes this possibility when she writes on “critical fabulation,” wherein the absence allows for something to grow, for truth to emerge in what the Black artist materializes grounded in a Black historical truth. Butler constructs moving portraits of Black life, and through this, she historicizes a consciousness of her experiences, enmeshing them with ruminations on community, love, and her own familial ties. We don’t know who each subject is, but they are real, and we see their most intimate and honest forms when we look at them in these portraits. Butler expands the possibilities of the quilting canon, directing and dialoguing new approaches to the discipline by working through the absence of an archive, and by narrativizing the social and political themes of her work. She takes on the question of Black joy and resilience in the face of growing political and social tensions in the United States, suggesting that in order to feel seen, one must seek safety in a tender closeness. Through this, she stewards what we know to be true across cultures, languages, and even words: that our memories are shaped by those who help us feel safe in our daily lives.

Butler traces some of her earliest quilting work to her own family, crediting her father for the materials that opened the door to the themes she continues to unpack in her work today. She explains, “One of my first quilts was an imagined portrait of my grandfather. My father’s from Ghana, born in 1939 in a more rural part of Ghana in the north. Very agrarian. And he doesn’t have any photographs of his dad, so I never knew what he looked like. That’s always been in my mind, you know, what did my grandfather look like? What did he sound like? What was he like? I decided that I would find a photo of an elderly northern Ghanaian man because they have a specific kind of look. When African people see me, especially if they’ve traveled extensively, they know not only that I’m Ghanaian, but they’re like, ‘Oh, you’re from the north.’ It’s something about the sort of long narrowness of my face and my nose. So, I found a picture of a man, and I made my first quilt.”

Bisa Butler

Coco With Morning Glories, 2024

After Coco, 1993 by Dana Lixenberg

Cotton, silk, lace, netting, tulle, sequins, glitter, beads, glass gems, metal beads, silk and polyester woven fabric and velvet, quilted and appliquéd

84 x 55 inches

Private Collection

Photo by Zachary Balber. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch, New York and Los Angeles

“I was using my father’s dashikis from the ’60s because I couldn’t afford fabric. I asked him, ‘Do you mind if I use these?’ not thinking. I just wanted African fabric because I thought this would be a good way to tell the story of a man from Africa. But it wasn't until it was done that I realized, oh, these are my father’s shirts. My father is one of those people who’s worn cologne his whole life. When I go into his room or touch his things, I can smell his cologne, and his shirts faintly smell like cologne. My grandfather's DNA is in my father. My grandfather’s DNA was in the portrait I made of him.” Butler’s lifelong dedication to her craft was solidified after this first project. “After seeing the Whitney exhibition on quilts at that time, I felt successful with that portrait. I felt like my father loved it. I loved it.”

An archival project in a stream of consciousness, Bisa Butler intentionally selects her materials to immortalize those who came before her in the fabric of time and memory. Perhaps this is what her larger project is: to solidify people in textural form. Textiles woven and stitched into each other, culminating into a whole that feels like we’ll know them forever. The exhibition was born out of our political time–the isolative, alienating properties of emotion Butler was working through. They leave us with a desire for our own versions of the depicted affections on display, a brazen introspection. Coco with Morning Glories (2024) depicts a pregnant woman looking into the distance contemplatively, a soon-to-be mother filled with warmth and hopefulness. She reflects, “Theorizing what I would put together really came from this moment that we’re in...I called the show Hold Me Close because that’s how I was feeling, like, goodness, I need somebody to hold me because I’m feeling terrified all the time. And that’s not a good state to be in. When we’re in a time of crisis, human beings, we usually band together. I was looking for images of people who were engaged in comforting each other, lighthearted moments, intimate moments. It could be mother and child, or father and child, lovers, friends. Most of the pieces in the show feature two people in them. There’s one with a very pregnant woman…. My grandmother had ten kids, and I was having my first daughter. I think I was exactly nine months pregnant. I was like, ‘I cannot wait for this baby to be born.’ My grandmother said, ‘This is the best time. You don’t realize it. Your baby is totally safe right now. You don’t have to worry. Are they cold? Are they tired? Are they hungry?’ The pregnant woman is also holding her baby very close.” Bisa Butler’s world of love is endless, is forever.