text and images by Perry Shimon

Over the ten years or so that I’ve been coming to Mexico City art week, it seems to have grown beyond what one can reasonably expect to see and make sense of. In the earlier editions, it felt as though there was a generous and loosely choreographed range of offerings that most guests largely experienced, and this provided a common frame that gave the proceedings a shared feeling of intimacy. The last several editions, however, have begun to produce that major-biennial feeling of anxious FOMO as events and invitations proliferate throughout the frenetic week. This feels a bit sad to me, as I used to regard my seasonal visits to Mexico as a balm to the usual anxious feelings related to trying to do too many things. I suppose this is largely a me problem—if a problem at all—and what I would like to offer in the following essay are some modest and affectionate reflections from a becoming-more-familiar tourist.

I arrived early enough to get settled in and have a limpia and a leisurely breakfast at the Zócalo. I love this limpia, or cleansing ritual, with all the sights and smells of the Indigenous healers beside the partially excavated Aztec ruins of the Templo Mayor, in the shadow of the grandiose Gothic Baroque Catholic church in the Plaza de la Constitución, on what was formerly known as Tenochtitlan on Lake Texcoco. The burning of rosemary, blaring conches, shimmering feathers—all a testament to an enduring Indigenous presence and culture. This beautiful ceremony activates the entire sensorium, plunging the participant into a sensual presence of deep attention, breath, and touch, while chimes and bellows dissolve you into a vibrational individuated state. Warm, herbaceous smoke fills the lungs, and cool, fragrant branches invigorate the body. I like to do this ritual upon arrival, just before departing, and sometimes after the ZsONAMACO preview.

PEANA Gallery

Patricia Conde Gallery

Material Monday, part of the generous extracurricular program organized by the Material fair, offered a coordinated set of bus routes around portions of the gallery circuit. It was a rather ambitious schedule, pretty much incommensurate with the slow social unfolding of each opening, and we made it to maybe half of the stops. A backdrop of largely forgettable paintings and libidinally charged, often BDSM-inflected objects and installations set the stage for the young and vibrant scene of international art crowds. A North American gallerist friend worried aloud about getting stopped at customs with some carry-on paintings that may not have been properly declared and informed me that last year the customs agents had Androids and slap-on-the-wrist fines, whereas this year it was iPhones, Apple Watches, Google Image searches, and an extra punitive zero.

I never quite got settled into yet another proliferating, ill-sized, generic Airbnb with IKEA-showroom furniture, faux-aged wall art, gratuitous Ganesh figurines, pallid lighting, cheap blunt knives, Amazon Basics plates, and an alphanumeric series of codes, lockboxes, and passwords. There’s a haze of pollution, undrinkable water, and structurally immiserated urban poor and rough sleepers, mostly left out of the otherwise extremely Instagrammable frame of the parts of Mexico City that art tourists, expats, remote workers, and hip affluent Mexicans have largely claimed—not necessarily in that order.

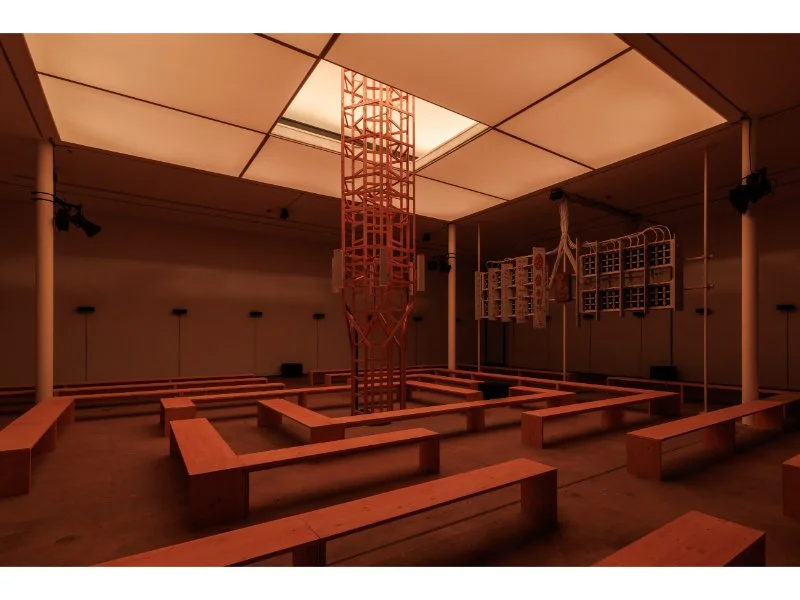

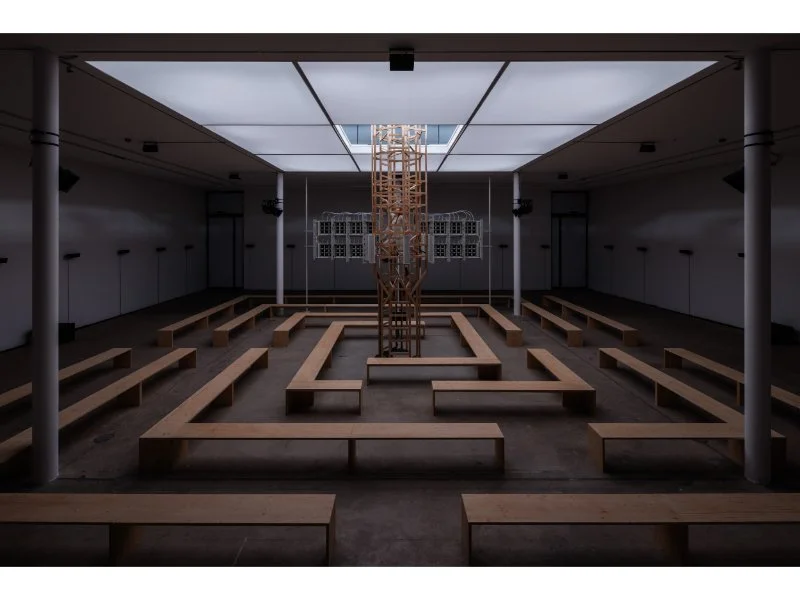

Inner Stage at Escuela del Ballet Folklórico

MASA Galería

There’s a kind of jouissance in playing spot-the-art-tourist, often found standing around in an ill-fitting, overly constructed, and colorful costume, looking transfixedly into their phone near some Michelin-rated eatery and largely oblivious to anything else happening around them. If sheer volume is any indication, someone at Michelin has fallen in love with Mexico City—or maybe someone from Mexico City has landed a senior position at Michelin—or someone has started bootlegging the Michelin signs. Whatever the case may be, you can’t go a block in Roma or Condesa without seeing a constellation of Michelin honorifics.

Enrique López Llamas at Salón ACME

The now oft-repeated synopsis holds mostly true: Maco is a tedious convention center filled with conservative art; Salón Acme is the most beautiful space and the most fun setting; and Material features the kind of art most resonant with the kinds of people who make these kinds of aesthetic judgments. This year, on account of Netflix buying out Material’s usual home on Reforma for an Immersive Stranger Things Experience, the fair moved to a soundstage in an adjacent neighborhood that responded with a smattering of anti-gentrification graffiti around the venue and entrance. Gentrification politics notwithstanding, the new location offered a welcome outdoor courtyard for convivial gathering between salon visits.

Material

Angela Maasalu at Tütar Gallery

Romeo Gomez Lopez

Sophie Jung at Copperfield

Tim Brawner at Management

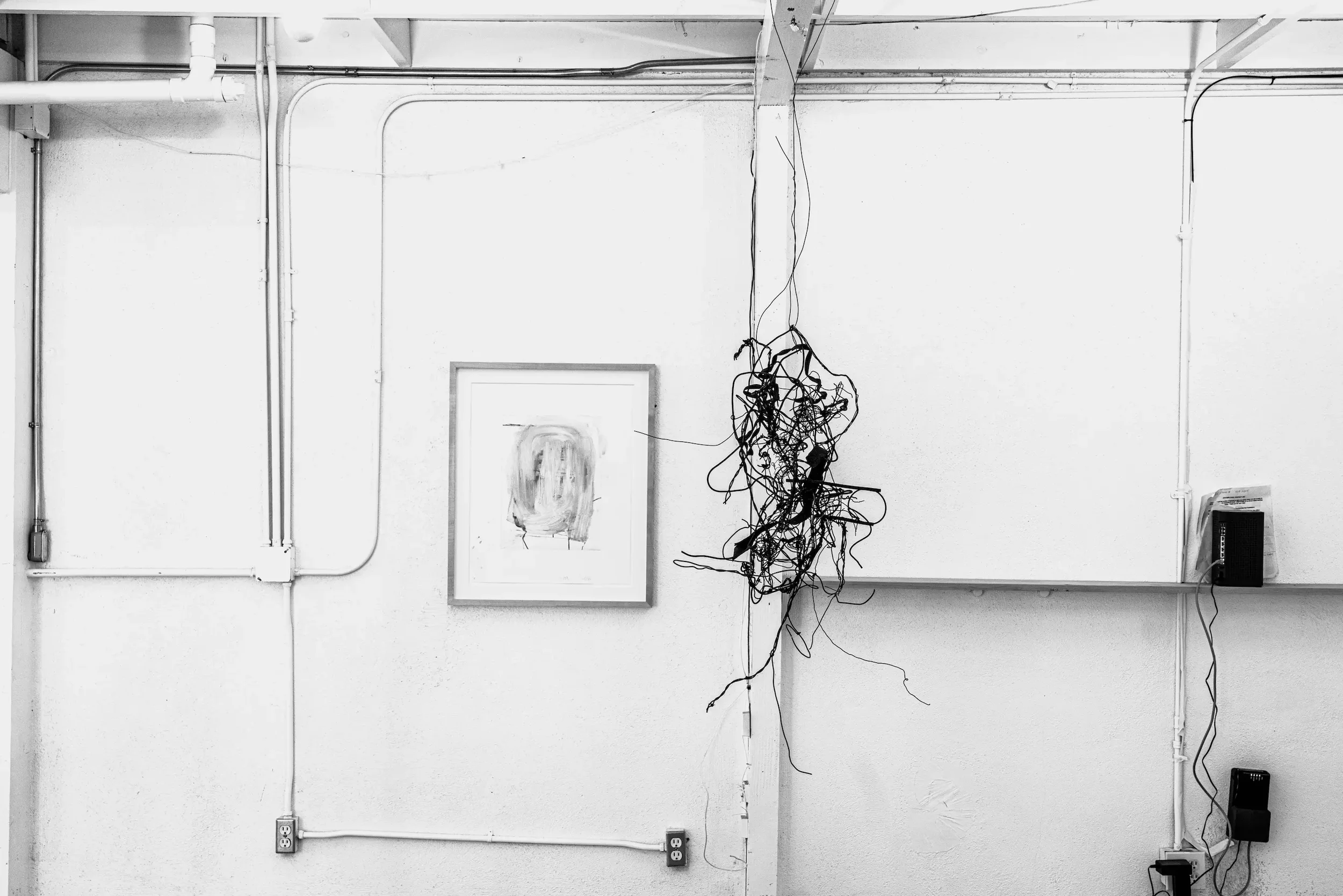

While the deracinated, standardized, and financially motivated confines of an art fair hardly offer the context to meaningfully present and situate artists and their work, the pieces on view in this edition—and more generally among a generation of artists today—seem to illustrate some widely shared tendencies in a moment of post-industrial capitalism in the Global North. Broadly speaking, I would offer a sense of alienation from both production and meaning: deskilling, appropriation, and insular, memetic self-referentiality. I got the sense there was a kind of semiotic slippage or drift, vectorized in niche corners and chambers of the internet, devirtualizing in the gallery and congealing into ambivalent fragments of semiotic disintegration. This is, of course, not without moments of beauty, curiosity, humor, irony, and so on. I also found myself wondering whether the promise of relational aesthetics—with its de-fetishization of the art object and return to the ritual object or practice that reinstates social exchange—has somehow not been delivered in Mexico City art week. Several gallerist friends jokingly confessed they don’t mind losing money, really, because of how much they enjoy coming down and hanging out.

Taverna

Salón Acme

Salón Acme has gotten many things right, and its now overbearing success—with overflowing crowds and lines around the block—is perhaps a sign that the lessons learned there could be more broadly emulated and publicly supported. The grand, crumbling Porfirian architecture and courtyard, featuring a large open call of emerging artists, always offer thrills and diverse social energies across a range of convivial and aesthetic zones: restaurants and cafés, verandas and vistas for people-watching, libraries and bookshops, rooftop dancing, and art installed on nearly every surface in between. It invites the question: why don’t we have many more spaces like this, with this level of public programming? Why don’t municipalities support more projects like this? France offers some possible models, with venues like Friche la Belle de Mai in Marseille and 104 in Paris.

Tania Pérez Córdova at Travesia Cuatro

Graciela Iturbide at Fomento Cultural Banamex

Around the fairs, the Mexico City art ecosystem is on full display, offering a superabundance of institutional programming, satellites, events, artist-organized shows, performances, and historic architectures. Each addition seems to unearth and activate some overlooked or underexposed modernist architecture with art installations or contemporary design objects. This edition, I went to the Pedregal neighborhood to see the Casa Alonso Rebaque home designed by Félix Candela. Last year, I went to a performance at a Barragán estate inaugurated as a cultural institute, and the year before enjoyed beautiful tours of the Juan O’Gorman–designed home and studio of Nancarrow and the home and collection of Mexican architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez.

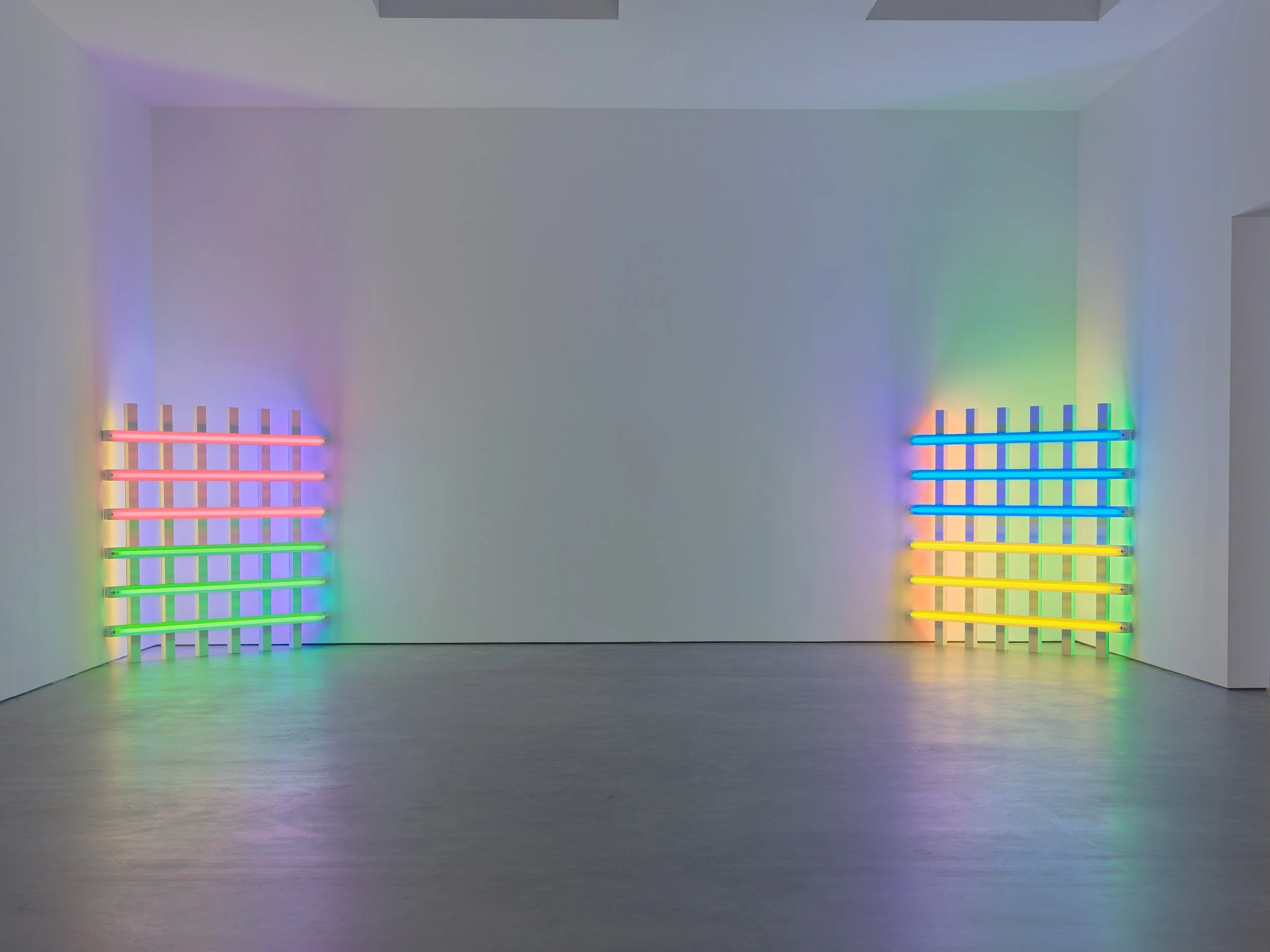

I arrived early at the new crown jewel of Chapultepec Park, LagoAlgo, to see an exhibition by the London-based collective Troika, who converted the picturesque gallery into bands of RGB-tinted conceptual explorations of machine seeing and increasingly automated, algorithmically determined futures. Stills of eco-disaster captured on CCTV monitors—the collective noted there are 500 million of such cameras globally and growing—were meticulously painted at pixel resolution, while trembling plants sprouted from piles of silicon and salt around the gallery. A large monitor intersected the space with a CGI-rendered KUKA robot twirling a mane of virtual hair balletically atop a green-screened timelapse of climatological fluctuation. A haunting choral score stretched a lightly remixed line from a Rumi poem—“a drop in the ocean, the ocean in a drop”—into different permutations. Eva and Seb, two-thirds of Troika, shared that they were interested in the way certain animals, like dolphins and wolves, compress meaning into concentrated semiotic calls delivered across great time and space, and we considered what relation this might have to our packaged transmission of data through the internet. The conversation took a fascinating turn into the crystalline structures of modernity and a longue durée technological history of orthogonal logic. I believe Seb at one point suggested a kind of conspiracy of flint rocks, silicon, salt, and even mathematics in dominating the organic world—which, actually, makes a lot of sense to me. I found Troika’s work compelling for showing the similarities between art and science, as they are both largely lens-based partial epistemologies often co-engaged with metaphysical and ontological considerations and decidedly committed to our technological moment of massive planetary sensing: a moment that empirically demonstrates the severity of our polycrises, yet can only seem to find ways to profit from them, while the energetic costs of mounting planetary surveillance reinforce a downward ecological spiral.

Walking out of the gallery back into the grand architecture of the museum café and looking out onto a terraformed lake—what was once a natural lake—alongside a private tour of Northern collectors and art administrators that prompted my friend to mutter “Mar-a-LagoAlgo,” was a somewhat grim, if tastefully tisane-palliated, reminder of how unevenly these climatological experiences will be distributed in our unfolding future.

José Eduardo Barajas’s La Blanda Patria

I went downtown to see the large group show Columna Rota (Broken Column), curated by Francisco Berzunza around the theme of rejection, borrowing its title from Frida Kahlo’s 1944 self-portrait with an Ionic column in place of her spine, made during a period of surgery undertaken to overcome a debilitating physical injury. It was a bold curatorial gambit to foreground feelings of inadequacy in framing a rangy exhibition of some 150 loosely related international works. Many of the individual pieces overcame the curatorial determination on their own terms and complexity, and I found myself thinking over the coming days about the role of the curator in an art world of increasing bureaucracy and professionalization, and the restructuring of value toward those who control the vectors of circulation. I also found myself wondering what more structural concerns might be established and staked to link the disparate works on view.

Tamiji Kitagawa’s Two Donkeys

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Pray, Bless Us with Rice and Curry, Our Great Moon

Approaching the show, I felt small soap bubbles popping on my skin and learned they were made by Teresa Margolles using a solution employed to wash the dead in Oaxaca. We encounter José Eduardo Barajas’s La Blanda Patria, a mural installed in the ceiling before the start of the exhibition, and are then treated to a broad survey of works, with highlights including Tamiji Kitagawa’s Two Donkeys and Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Pray, Bless Us with Rice and Curry, Our Great Moon—two works suggesting a more-than-human conception of rejection and overcoming. The show ended with a small comet study by José María Tranquilino Francisco de Jesús Velasco Gómez Obregón—or Velasco, as he is commonly known—whose work was contemporaneously enjoying a beautifully conceived retrospective at the nearby Kaluz Museum, housed in a restored and transformed viceregal hospice.

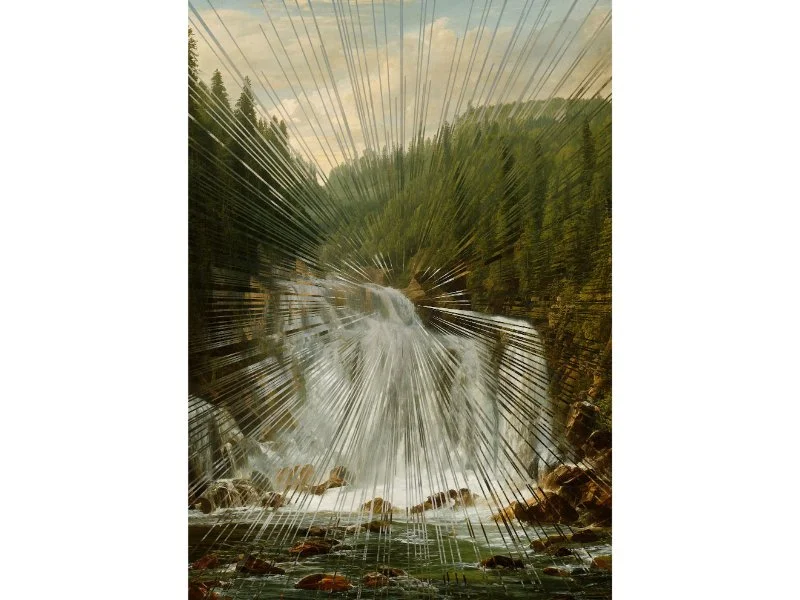

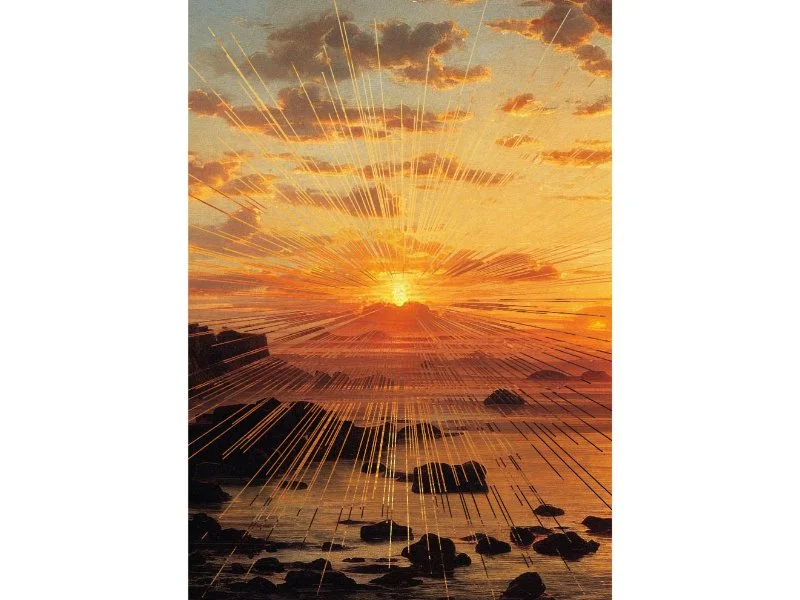

The Garden of Velasco at the Kaluz Museum draws from a collection compiled and acquired from the artist’s great-granddaughter and includes over 2,500 previously unseen paintings, notebooks, sketches, letters, manuscripts, books, and objects. The exhibition assembled from the archive is extraordinary in both selection and museography, and contours a brilliant polymath artist alive to his time in a critical, contemplative, self-reflexive, and ecological register. His journals, palette, and early experiments with photography provide beautiful insights. Taken in aggregate, the work rigorously engages a fraught modernist romantic regime emerging with its many internal conflicts and paradoxes, alongside enduring legacies of the construction, subordination, and instrumentalization of Nature.

UNAM’s MUAC galleries, ever a discursive force in the Latin American art context, offered a suite of compelling presentations, including an exhibition on Mexican collectives invited to the 10th Paris Young Artist Biennial in 1977 to show their aestheticized political work—perhaps a timely revisiting of this history in light of the recent documenta’s focus on the collective form—as well as the contradictions and tensions that emerge from exhibiting embedded, politically oriented collective practices within the European biennial format and the larger neoliberal context.

Los grupos y otras

Alongside Los grupos y otras, there were presentations of Marta Palau’s earthen textile, wooden, and ceramic works, and a large site-specific installation by Delcy Morelos, titled Womb Space, submerging the viewer in a chamber of fragrant earth. As surprising and pleasant as it was to encounter, I couldn’t help thinking of Jainism and how it might regard this work. Their sophistication of ecological awareness and ethics is so refined that they won’t harvest and eat allium vegetables so as not to disturb the microorganisms and surrounding insect life. It also evoked for me a kind of extractivism difficult to reconcile with the maternal invocations, and made me wonder about the labor and ecology of this presentation, as well as our implication in various forms of extractivism—for the purpose of making beautiful art installations, or mining the rare earth minerals needed for me to write and share this review.

Marta Palau

Delcy Morelos

The telluric theme ran through the Tamayo Museum, newly helmed by Andrea Torreblanca, who curated the gorgeous Archaic Futures exhibition in the downstairs galleries. The framing was both light and grand in its invocations of universals, archetypes, and cosmos, assembling, with high modernist elegance, a suite of recurrent natural motifs and sumptuous abstraction. In the airy atrium, now dedicated to relational art, appreciative visitors rested in a lattice of sweeping, undulating hammocks—a thoughtful and welcome reprieve from the art week’s velocities.

Archaic Futures

An artful highlight of the week, in the somewhat ironically named Arte Abierto space in a posh mall in Pedregal, was the painstaking, fragile, and menacing Temporal Advantage installation by Mauro Giaconi: a life-size ship made almost entirely from paper, graphite, and silicon, installed in a rooftop white-cube gallery. The impressive and beautiful work, compiled from thousands of sheets of paper—each skillfully rendered in graphite to evoke patinated metal—constructs a stalled, precarious, and ominous vessel filled with secrets, questions, and paradoxes. Upstairs, growing on the deck, was a garden made from machete blades; downstairs, a kind of galley kitchen with steaming pots resembling bomb equipment. One hidden real tin can sat on a shelf of paper ones, containing instructions for how to make a secret chamber in the base of a can to smuggle correspondence. A single book placed on the floor beneath a paper bunk bed was titled: La simulación en la lucha por la vida.

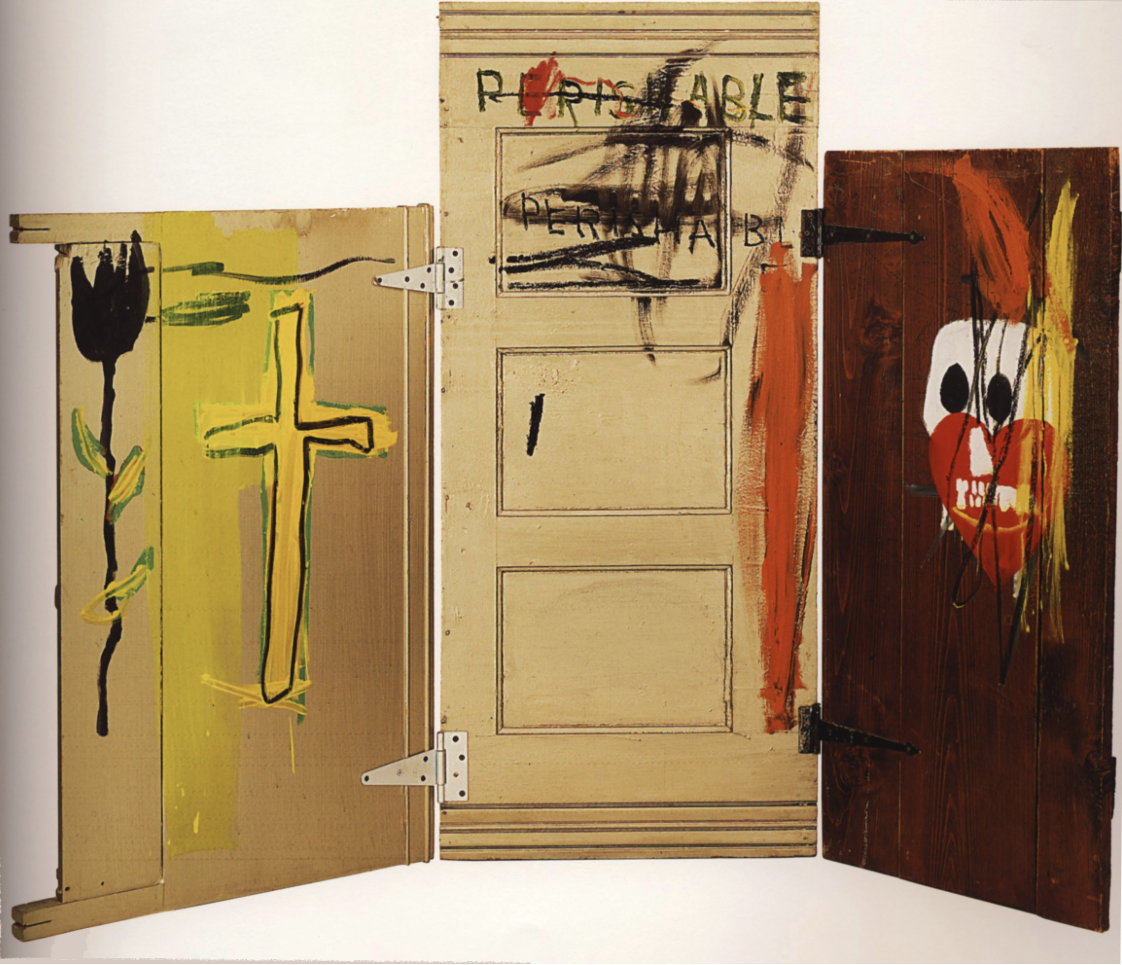

Casa Wabi and Kurimanzutto offered case studies in beautiful architecture squandered on the presentation of overvalued individual artists. Meanwhile, the cheeky Purimanzutto popped up in a historic gay club and offered a lighthearted exercise in the radical subversion and reappropriation of a rigorously oppressive—if not contiguously gay—variation of Christianity, with campy, queered iconography and crucified Jesus disco balls adorning crowds of working-class local youth singing and dancing along to reggaeton anthems.

Guadalajara90210—whose 2019 Pabellón de las Escaleras 100-artist group show in an open-roofed building under construction in the Santa María neighborhood remains one of my greatest memories of Mexico City art weeks past—presented a sprawling forty-some-artist group show in their new space, alongside a solo presentation and a concentrated version of their last exhibition in a smaller gallery, combining small sculptures formerly stretched around the circumference of the gallery onto three shelves of densely wonderful works. Their plural, playful, social, and distinctly Mexican modernist approach to exhibition-making has made them beloved scene-makers in the flourishing Mexico City and Guadalajara milieus.

Joshua Merchan Rodriguez

Some of my favorite artistic interventions occurred at the infrastructural level. The dedicated public bus lanes that speed past gridlocked individual automobile traffic are a marvel of relational aesthetics. Parque México is a near-perfect and democratic achievement of social art that should be reproduced as widely as there are neighborhoods. Sitting in the central plaza, where every generation lingers and plays, and wandering the meandering paths filled with more-than-human life, I feel a sense of hope and contours of the otherwise.

Sunday dance group in the plaza

On my final night, I found my way to a deconsecrated church where the brilliant visual ethnomusicologist Vincent Moon had installed himself, with the help of local event producers Love Academy, for a twelve-hour durational live performance and mix of his thousands of music films produced around the world with ritual and devotional musicians. His approach felt shamanic and reverential, and I was moved to tears lying barefoot on the lushly carpeted and cushioned floor with an intergenerational audience enthralled by the sonorous beauty of our world’s diverse cultures and art forms. After the performance, Vincent stayed around, giving hugs and answering questions about his practice and equipment. He shared his humble thanks to the artists he has met and tenderly portrayed, and noted that all of his films are available for free for anyone to watch on his website.

The next morning, a final limpia and a return, fortified with beauty and ritual, to a dark and depraved, terrorizing Trumpian North America.