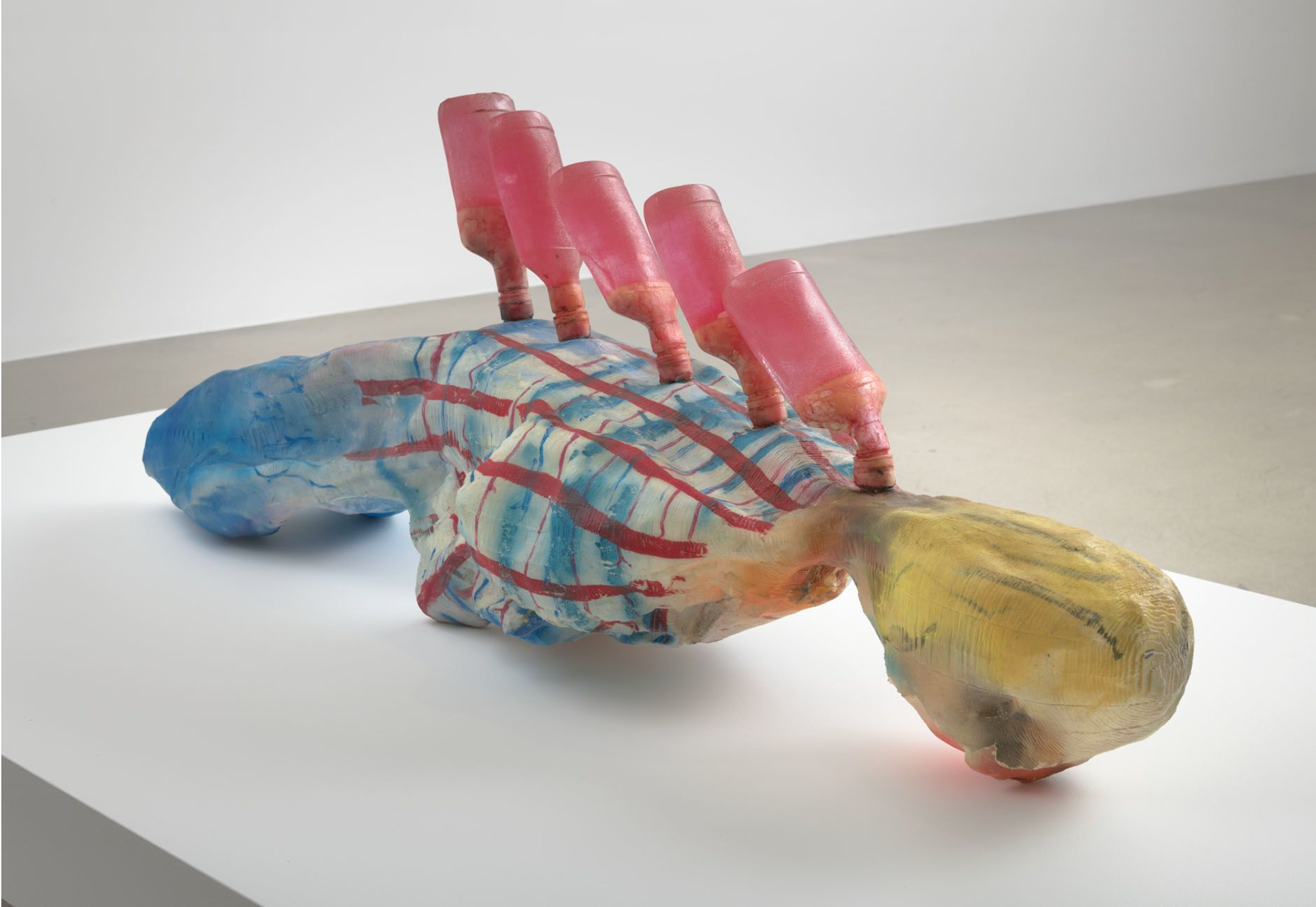

Kaari Upson “Kris’s Dollhouse” 2017-2019 (detail)

A pierced clit from beyond the grave—its folds and sensuous creases climb like a corpse flower too shy to bloom. A sheath covers something secret. A Christmas tree, covered in plastic, sutured closed forever by two rings. This sculpture, a detail from Kris’s Dollhouse (2017-19), is one of Upson’s many abstract and mysterious enlargements—part of a grander picture, a paroxysm of materiality, a puzzle piece from the infiniteness of memory. A hazy, drunken recollection of a family home in a dream. Profane, but holy, and nearly archaeological. In her posthumous exhibition, now on view at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles, Upson mines the psychosexual miasma and violent ecological grandeur of the Southern California suburbs and its surrounding environs, always tiptoeing on the edge of danger, which is even more haunting now in her mortal absence (Upson died after a long battle with cancer in 2021). Memory is both the canary and the lantern, guiding her into the carbonized cave of our deepest desires. She looks to Freudian and Lacanian analysis as a mirror and the obtuse chromium coating behind the mirror, which renders glass not as a window to peer through, but our reversed double. Walking through the exhibition is like walking through the ruins and artifacts of an artist rushing through the pangs of mortality like a flash flood. Each work is a notation on an emergency: paintings thick with the impasto of life’s sediments, sculptures tortured by unrecognizability and large-scale drawings become like maps of the artist’s psyche, now frozen in time.

Kaari Upson never, never ever, never in my life, never in all my born days, never in all my life, never is on view through October 8, 2022 at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles