The word graffiti comes from the Italian word graffio, which means to scratch. The Ancient Romans would write their names and protest poems on buildings. Since the 1960s, artists Judith Bernstein and Paul McCarthy have been brutally scratching the surface of the American Nightmare with inspiration from the psychological graffiti of its violent and totalitarian collective subconscious. Bernstein had her revelation by absorbing the rude hieroglyphics scrawled on the bathroom stalls in the men’s room of her alma mater of Yale—McCarthy’s landscape was California; its dark optimism and congenitally blind ambition. Together they meet at the intersection of a disillusioned dream.

PAUL MCCARTHY I'm not sure when I discovered your work. I think I knew of the screw paintings from magazines. When did you start making those?

JUDITH BERNSTEIN I started in about ’69 and I continued them through the ’70s. I got a lot of brouhaha with those. I was censored in Philadelphia. There was a show called Focus: Women's Work—American Art in 1974 at the Museum of the Philadelphia Civic Center. It was curated by Cindy Nemser, Marcia Tucker, Lila Katzen, Adele Breeskin, and Anne d’Hanoncourt. They chose 86 up-and-coming and well-known female artists. When they saw my work, they said, “Oh no, we can't have that. It's pornography. All the kids will be damaged forever.” It went all the way up to Mayor Frank Rizzo. But there was a petition in protest that was signed by a lot of very well-known people, like Louise Bourgeois, Clement Greenberg, Linda Nochlin, Howardena Pindell, and Alice Neel. So, that's how I got more on the map.

MCCARTHY My interest in your work is probably related to how I viewed art and society at that time. I made these pieces in the mid-60s that I called the “Black Paintings,” which were eight or nine feet tall. They were based on a dragster car—like if you take a drag car and look down on it from above. The image was abstracted and flattened out. At the top was always this masked head, a gas mask. It was man, as machine—like a screw, but like a machine. So then, with the masked head of the man at the top, it was a totem stack, it was like a standing dick. Those paintings were all done between ’65 and ’67. They were always painted flat on the ground and I would be on top of them. They weren't painted with a brush but with a rag. And there was a frame about two inches off the plane where I would pour gasoline. Then, I would throw a match in and burn them. I was thinking about this today: with the trajectory of all my work, there has always been a similarity in a certain kind of critique of power structures and the patriarchy.

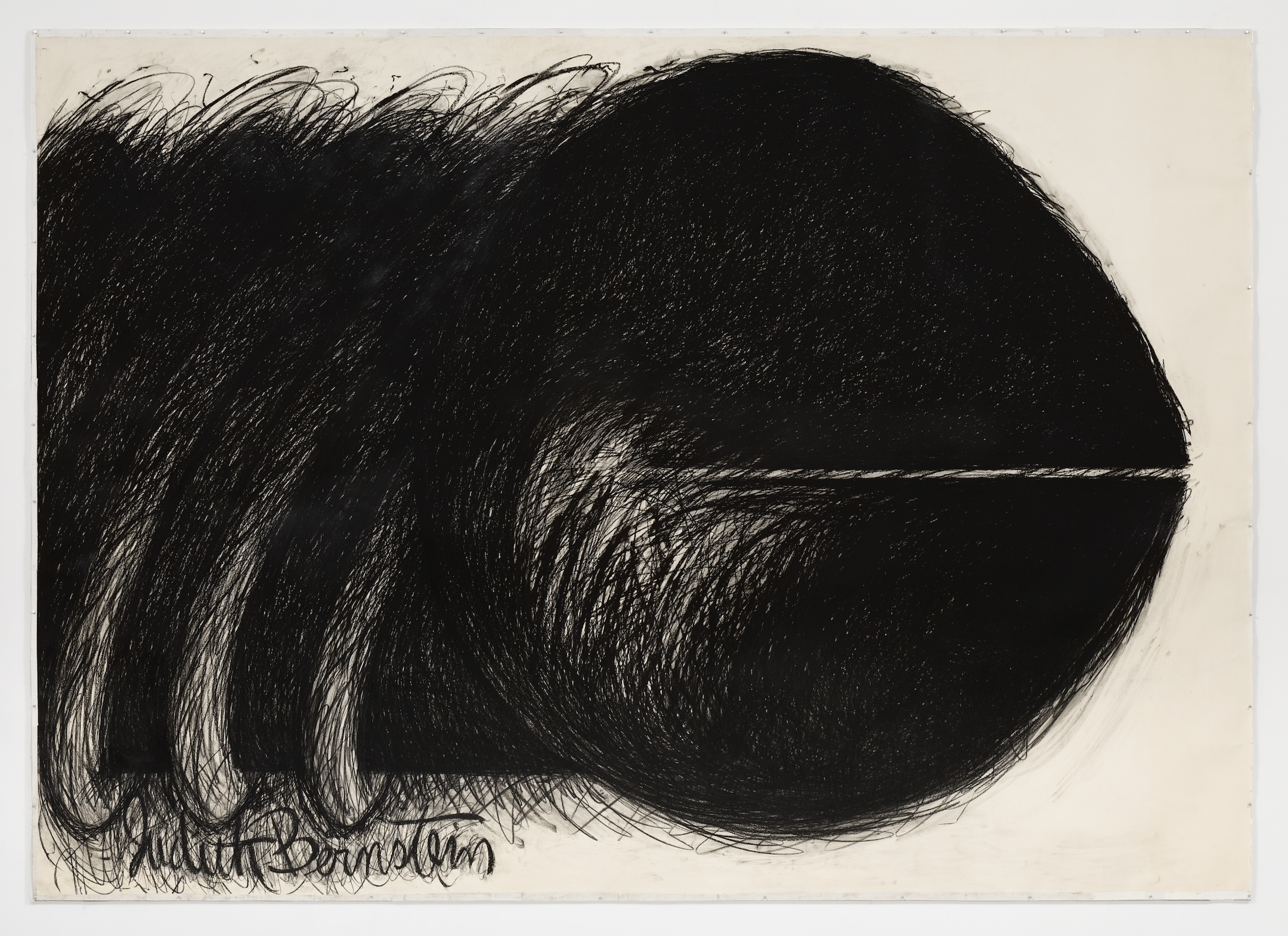

BERNSTEIN With the work that I was doing—the screw is a power image. It was a combination of masculinity and anti-war. They were also about feminism, like mine's bigger than yours. And actually, that screw drawing, the horizontal one shown at The Box, I recently sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which I'm thrilled beyond belief about. Nevertheless, it was once something that was censored. I always think that women, although we don't literally have a penis, we can certainly have access to the imagery. So, as I said, mine's bigger than yours, because the size was nine feet by twelve and a half feet. But, you know, it's funny because a lot of people think that I do some of these drawings when they're flat on the floor, but I don't. I always make them on the wall, so I can get farther back and be able to see the whole image.

Paul McCarthy, Performance still from Bassy Burger, 1991

© Paul McCarthy, Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

photo: Vaughn Rachel

MCCARTHY Mine is the opposite. I'm not often standing back to look at it—to judge it. It's always a shock when I look at it, and that's still the case. I didn't paint paintings on the wall until 2013. I viewed the paintings and drawings as an arena, like a room: it's on the floor or a large table and I'm moving around on it. It's a different experience, but the trajectory of painting and drawing is something that you stayed with. I was never attached to one medium—it could go in all directions simultaneously. But the connection between us is to that period of time in the ’60s, the institutions, and the war in Vietnam as a grounding point for suspicion and mistrust in the government. And of course, the subject of the male patriarch and the female. Even very early on, the words “Adam” and “Eve” came up in my work as a kind of joke or something. But always, there's this thing of portraying myself, the male, as the buffoon.

BERNSTEIN It's very psychological. And it’s much deeper than actually the buffoon because it speaks about a lot of things in your subconscious. And I do the same thing. When I actually make an image, I don't think about it. I get the general idea and then I do it. And then, later on, I think about what I've actually done.

MCCARTHY I think back to the ’70s, but it became more pronounced in the ’90s—I would only describe it as painting or drawing in character. It's not so much about inhabiting an accurate interpretation of Walt Disney or Hitler, that’s not the point, but I talk all the time. And I realized at one point, I talk as if I'm drunk. And the drunk character, the brave character, likes to destroy the good paintings. In performances, I do get drunk. By the end of a performance, I can be pretty drunk.

BERNSTEIN I think you have access to the subconscious with that. I know my own work is autobiographical, and I think that your work is also autobiographical. There's a lot of self-portraiture in spite of the fact that you're using characters that are outside yourself. And it's also very much a performance, Paul. The work is very performative. I consider my work somewhat of a performance, but yours is even more so because you're literally in the painting itself, or in the drawing, or in the piece of sculpture, or whatever you're doing.

Judith Bernstein, Gaslighting (Blue Ground), 2021

acrylic on canvas, 90.5 x 87 inches

courtesy of the artist and The Box, Los Angeles

MCCARTHY I've done a number of them where the action on the painting or on the drawing, there's someone else there, like the ones with Lilith Stangenberg. It's like creating this distraction. I would draw for three or four hours in these sessions. Somebody said, “Your paintings, your performances are like trances,” or, “Are you in a trance?” And I go, “Well, no, but there is something about focus and a form of involvement in a character that affects what I do.”

BERNSTEIN There is something about being in a trance. I know that when I'm painting, I have to finish it up because I'm in a zone and I don't want to wait until the next day. You're in a zone and there's something that is beyond you. It's interesting because when you have another person there, it's a happenstance that they are actually part of. And I do think, in essence, it’s like you're drunk. And there's something quite marvelous about it, because in a way it feels like an out-of-body experience, like someone else did it. I’ve heard Bob Dylan talk about this.

MCCARTHY There's this schizophrenic experience going on. Like I said, now I'm painting with the canvases leaning against the wall. It's like a whole new thing in a certain way. But I actually still try to get very close. I mean, literally two or three inches from them. I lean on them. I put my face on them.

BERNSTEIN Just in your face.

MCCARTHY I get very, very close and sometimes I stand back, but it'll go back and forth. And then you look at it and you go, I really like that one. And then, later you go, I've hated it ever since I started it. Yet it's almost on the edge of being something. But I know that the only way I can really get to it is to destroy it and start over. And then, I will talk constantly. And I'm saying these things to myself. The character always goes, “You don't trust it, Paul, do you, you don't trust. Paul doesn't trust me. Paul doesn't trust.” And then he goes to this crazy one: “Paul doesn't trust God.” You could say the drunk pretend character is crazy.

BERNSTEIN Well, we are the god of our work. Many times you'll have some extraordinary drawing, and then you'll just smear the whole thing over. Maybe it's too perfect. How can you actually be even more creative than you did the first time around and bring something else to it that you didn't the first time around?

MCCARTHY Do you paint over the top much?

BERNSTEIN It depends. I made a painting recently where I didn't get the color I wanted. So, I blacked out most of it. Then, I went in and did something entirely different, and I liked it better. Most of the time I do paint on top, but not much. I know when I geot it, and then I move to another painting. It's almost like the game of telephone: you do one thing and then it moves to something else, and then it transforms into something else.

MCCARTHY I paint over the top more now than ever before. Sometimes I think, oh, there's like six paintings underneath there.

BERNSTEIN I bet they're all as good.

MCCARTHY Maybe. I'm interested in painting over the top of paintings and keeping it going in a certain way—to keep the mental state going.

BERNSTEIN It's a great mystery. And also that mystery is a great gift because there's something so hallucinogenic about that. I use “We Don't Owe You A Tomorrow” because you don't know what tomorrow is. I think there's something very childlike about the world. They go into a room and they mess everything up, and then they leave and go into another room. And that's basically what we've been doing with our planet. We're so primitive in some ways, yet so technologically advanced. But it's still that motivation for power. As an artist, it is power over your own work. We think that it's only now that we don't want to pay the price of the future. But unfortunately, the future is now, and it's moving exponentially faster.

MCCARTHY Since the ’60s, I’ve been fascinated by the subject of fascism. Also, psychology, the subject of repression, and all the Freudian stuff. The discoveries of Wilhelm Reich's book Mass Psychology of Fascism (1933), Norman Brown’s Love’s Body (1966), Herbert Marcuse, Sartre, and R. D. Laing, and, of course, then you discover Duchamp, or John Cage, and then art and life become a thing. And then, there’s the subject of film and the moving image. It was critical for me. It's in California, but also you have the Europeans: [Jean-Luc] Godard and [Ingmar] Bergman. But there was also experimental film: Warhol was interesting for me, and Jack Smith. I was interested because they were dealing with the weird subject of the pretend. And on top of that, you have the political critique; the attempt to understand the absurdity of what humans have created. This thing of fascism and repression, as well as the subject of the phallic and the vagina, appears in both our work very early on. Is it a penis? Is it a vagina? What is it? This thing of desire and the pleasure principle versus the reality principle. But in the past twenty years, the subject of fascism continues to come up. In the last five years, I've been doing performances in the character form of Adolf Hitler. And the character that Lilith plays is Eva Braun, but she's also referred to as Marilyn Monroe. At some point I asked, what male stands out in Western culture? Is it Adolf Hitler? Is it Jesus Christ? And what's the female? Is it Marilyn Monroe? And of course, the two together are crazy, right? We're not trying to be in the ’40s or anything. It’s some sort of version, some sort of pretend play in a very ultra-serious, ultra-dumb, and ultra-buffoonish way. I’m pretending to be an American Adolf Hitler and Lilith is a German Marilyn Monroe.

BERNSTEIN It's goddamn serious, but it's actually so surreal. Trump brought back McCarthyism, Roy Cohn, and all this stuff that's out there now. And also Putin. I use the swastika. It's only a Nazi symbol at this point, not a Buddhist symbol. There's permission now to have a lot of this horrible fascism. It's much more accepted. It's very terrifying for those of us who know how horrible fascism can be—the extremes of fascism: death and concentration camps.

MCCARTHY But the goons or those who follow these characters, do they understand how the propaganda is being constructed? Do they recognize it? Their notion of what fascism is gets to be pretty small and pretty limited. And so they reject that. And then, you wonder about Trump—who is he and what is he? A few years ago, when we were remaking Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974), the Max character I was playing in my version, Night Vater, was not actually the Nazi officer that Dirk Bogarde plays. I become like a character living in California that produces films. The image I made was very mafioso in a clichéd way. The connection between government, fascism, and mafia or organized crime is real.

BERNSTEIN All these characters, they're two sides of the same coin. They're terrifying and very seductive at the same time.

MCCARTHY The one thing that has happened in these pieces that we've done is that the Eva Braun character, or Marilyn Monroe, becomes a mother, and a daughter. And Adolf Hitler is a father and a son. And they switch these roles. It’s built into the script that if the female kills the male, it's in response to the actions of the male. It's in response to who he is. And when the male kills the female, it's mean. It's the berserker. There's a difference in how violence towards the other happens. With the male, there's an insanity in there that comes out in these plays that we do. He’s a very ugly buffoon goon and a lush drunk character.

BERNSTEIN The male can be very ugly because it's killing his mother. The father is someone who has had physical power for so long. It's complex because it goes all the way back to the primal family, and it's very primal.

MCCARTHY There’s also the crazy part of how all this is understood, like how somebody reads this kind of imagery. How do they deal with the subject of irony, sarcasm, metaphor, or caricature? How do they understand the language of art? It's a forum, an arena. The idea that as an artist you have to know your intentions before you begin. How art is talked about, I’ve sat in on crits in colleges, and there is an emphasis on having a correct idea before you make the work. Then, the question is about how well you’ve carried out your initial intentions, so how good the work is would be determined by how well you’ve completed your intentions. What is frowned upon is working from an idea through a process to get to an understanding, allowing yourself to change, and resolving issues in the process, letting the process move the work. But also, in this way art can expose something. What scares me right now is the type of criticism that's going on. I was censored in the ’60s, but I've been censored more now than ever before. In one way, as the world gets more extreme, you would think it's natural that art would inevitably become more extreme in response.

BERNSTEIN I hope that's the case, but I don't know. It may become more simplistic.

Paul McCarthy with Lilith Stangenberg, Performance still from A&E, Adolf and Eva, Cooking Show, 2022. Directed by Damon McCarthy © Paul McCarthy, Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Stevens.

MCCARTHY But a lot of that is the market and the art world. The art world as a market controls so much of what we know of art. You know, like what the gallery shows, but really what the museums show. And then, you know, who's on the board, and who the curators and directors are, and how the money flows. I went to a gala a few years ago and a film director got up and said, as part of his speech for the award, “Remember, if it's not popular, it's not art.” Nobody said a thing. In fact, people clapped. And I thought, oh, god. It becomes propaganda. Imagine that statement moving through an audience of five-hundred or six-hundred people. Then, you have museums creating shows that are popular and counting people that are coming and going.

BERNSTEIN It's all intertwined, Paul.

MCCARTHY Yeah. It's all entwined. It also has layers to it. In some ways, the art world has opened up and in other ways, it's closed down. It's a strange combination. It may indicate that we’re in a transition. But the seduction of money is huge. You and I, in some ways, have experienced the same art world, but in different locations. You've been primarily in New York, and I've been primarily in California. There’s an interesting difference. But there are a lot of levels where our work connects. I think it was Mara’s [McCarthy] idea that I would curate your latest show, We Don’t Owe You A Tomorrow, at The Box. Maybe there's less to say about the curating, and more about the paintings. There was a question about the black light paintings. I think if we could have afforded it, I would've turned the whole gallery into a black light situation so that you really had a chance to see these paintings in the two situations.

BERNSTEIN I put a black light on stuff so that you have a parallel universe. There's something very mysterious about the way I handle it because I make a painting and then I see it under black light after it's finished. In a way, it's like a surprise. I thought about the work being mostly about this nightmarish zeitgeist. Also, I'm very much into humor, just as you are. But mine has a different kind of black humor. I think that humor makes the work more accessible and more memorable, but also that it makes it easier to accept. Laughing—it's almost like an ejaculation.

When I was a graduate student at Yale, I had the idea to go into the men's room. I read an article in the New York Times, and it said the title of Who's Afraid Of Virginia Woolf (1962) was taken from bathroom graffiti. Right away, I was off and running. Graffiti is actually much deeper than you expect. And the same with your work—you have stuff that is so psychologically charged. I also use these great limericks: There once was a man from Nantucket who had a dick so long he could suck it. All those graffiti pieces led to the Fuck Vietnam pieces and the large projectile phalluses. I was always so interested in doing things that express my rage at injustice. My rage at the Vietnam War was extraordinary. My work has a lot of energy and a lot of balls. There's something so primal and so primitive about painting and just putting your whole self in it, your whole life in it—it's been an extraordinary trip.

MCCARTHY I think the paintings you've made in the last few years kind of indicate a sense of speed and quantity. You know, quantity is a subject or part of what I'm doing. The idea of the studio being a B- movie sound stage. But the thing that's happening now is digital quantity. There are hundreds of thousands of images, but it’s also video—there’s more video than we can possibly ever edit. For me, the accumulation of imagery becomes a piece in and of itself. The hard drive that holds all the images is the object. At one point, all my videotapes in the ’70s were in cardboard boxes, and the cardboard boxes were stacked like a totem. The subject of stacking has gone on in my work since the ’60s. So, I stacked the videotape boxes and it was sold as a sculpture. The object is the boxes that hold the videotapes. I think there's something about the unseen and the skin of the box is like the skin of the person and inside it holds the information. For me, they become kind of metaphors for the body. Now what I’m doing, intentionally and unintentionally, meaning it’s just happening, is the stacking up of hard drives. I would say that a good portion of what I've made in the last ten years doesn't even get shown. It has no place.

BERNSTEIN Yes, but you got a chance to do what you wanted to do. And you know something, you don't know what will happen tomorrow.

Judith Bernstein in her studio in New York City. Photography by David Brandon Geeting.