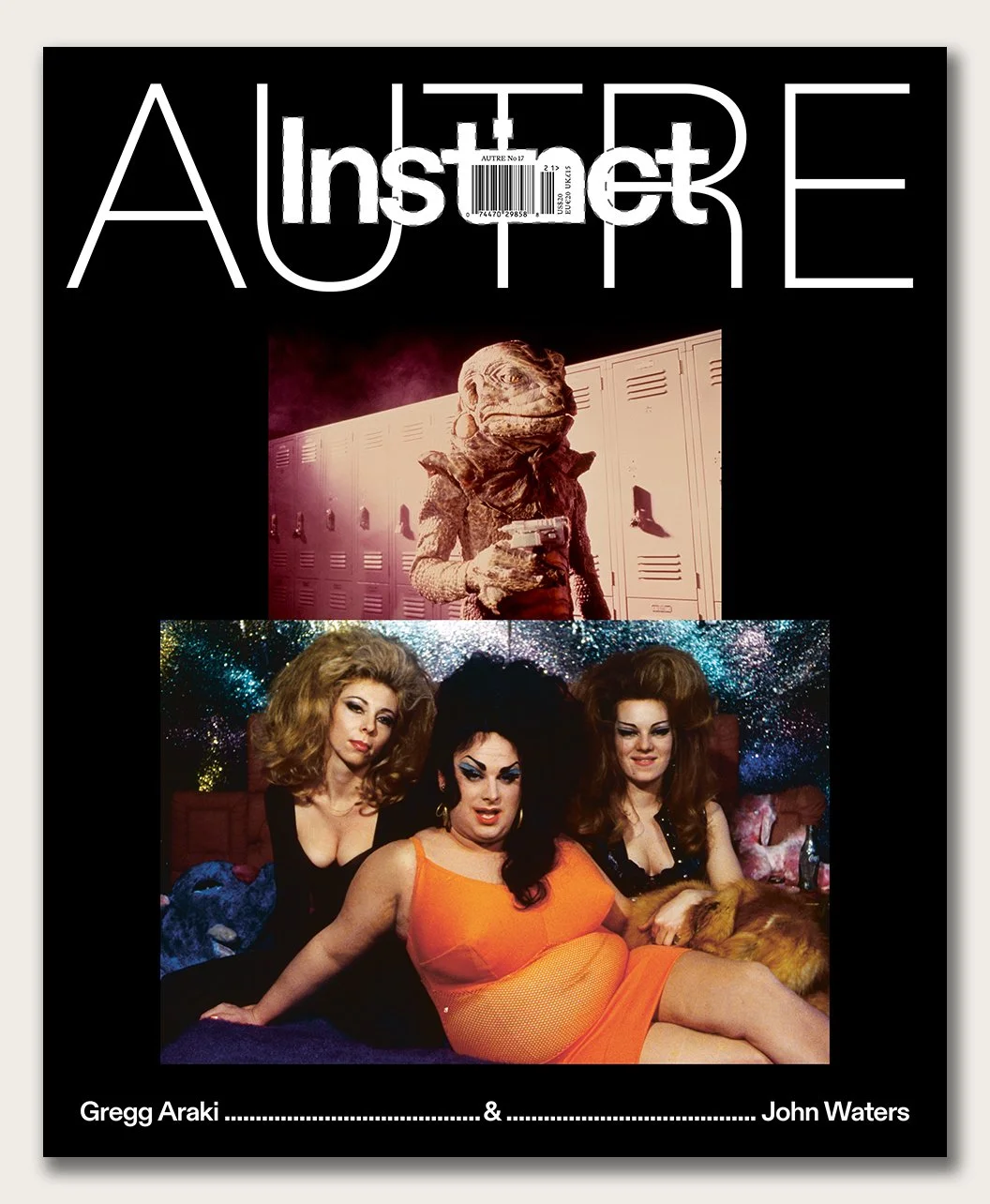

Disdain for authority, wide open sexual fluidity and addiction, homicidal mania, perversion, bodily secretions, religious blasphemy, bestiality, incest, and pedophilia—John Waters and Gregg Araki’s pornographically electric gems of silver screen beauty have forever changed the cinematic medium. In the fall of 2023, John Waters will see his first comprehensive directorial retrospective at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Pope Of Trash will have costumes, props, handwritten scripts, correspondence, scrapbooks, photographs, film clips, and more. At the same museum, Araki will present the world premiere of his newly restored queer classic Nowhere (1997), alongside Totally F***ed Up (1993) and The Doom Generation (1995), which comprise what became known as his Teen Apocalypse Trilogy. In this historic, career-spanning conversation, Waters and Araki discuss their lifetime of celluloid perversions.

JOHN WATERS I'm against instinct. Do you know why? I resent that I have to take a shit every day. I resent that I didn't think up sex, but I have to do it. Anything that isn't my idea that I have to do, I hate. But it’s amazing that some people think they have invented things.

ARAKI I feel like you did invent things. That's why, to me John, you're like the North Star. You're the OG one, right? I mean, there were obviously underground, experimental filmmakers before you, like Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren, and all that stuff, but you brought it all together. I feel super fortunate. In the age that I was born, there was punk rock music, New Wave music, Queer culture, Sundance, and indie cinema. Everything in my career, all the films I've made, have lined up with this timeline of the rise of indie cinema. I was just basically in the right place at the right time. But you're about ten years ahead of me.

WATERS I know, but still, I lived in Baltimore. You lived in LA where you could see these movies. I just read about them from Jonas Mekas’s column, or we'd go to New York and see them. But I saw Jean Genet movies, Kenneth Anger (like his first film Fireworks [1947]), the Kuchar Brothers, and Warhol. Certainly Warhol. At the same time, I was watching Russ Meyer and Herschell Gordon Lewis movies.

ARAKI For my generation—filmmakers like Christine Vachon, Richard Linklater, Allison Anders, Gus Van Sant—it felt like a high school class. There were Sundance and independent distributors. There was a structure for indie cinema that existed in those days that was sort of growing as we were all making movies, and we were all growing as filmmakers. But you were kind of before all that, you know what I mean?

WATERS Underground cinema was really non-theatrical except for the main three cities. Where you went is the college market and it was huge. That's where people went to see my movies. We toured college markets everywhere.

ARAKI I remember seeing them. They used to show them on 16mm.

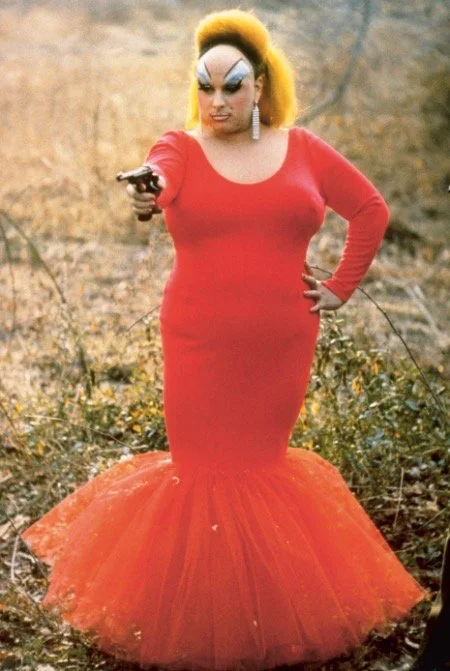

WATERS …And I'd come out and Divine would throw dead fish in the audience and a fake cop would come on stage and bust us, and Divine would strangle him, and the movie would start. We had a vaudeville act.

ARAKI So, American indie cinema didn't exist before.

WATERS The way it existed was The Film-Makers' Cooperative, which was founded by Jonas Mekas. But there were way less places to play.

ARAKI And also way less populous. Do you know what I mean? I remember seeing Kenneth Anger in an experimental film class when I was an undergrad. It was very underground, but it didn't have that element of entertainment and comedy. It didn't have what you brought to it, you know, the vaudevillian. (laughs)

WATERS Really, I made exploitation films for art theaters. And there wasn't any such thing as that really.

ARAKI As I said, you were the North Star. You were the one that paved the way for everybody.

WATERS Well, that's very sweet. I was a mudslide ahead of you. (laughs)

ARAKI (laughs) I mean, it's real. Your significance in that world is never to be questioned. I was always in the right place at the right time, but you were even more in the right place.

WATERS No, I was in the wrong place at the wrong time! I still am. I still live in Baltimore. If I had ever moved to LA it would've been the worst thing for my career because they would've gotten used to me. And then when I’d go pitch a movie, they’d say, “Oh, we'll see him at a party next week.”

ARAKI But you were there for everything. You went right to Studio 54, right? Like with Halston and all those people?

WATERS I hated Studio 54. No, we made fun of that. We were at the Mudd Club. We hated disco. No, I couldn't stand Halston, actually. And he had the worst boyfriend ever. He was too much of a pissy old queen. I was at the Mudd Club, I was at Area. We couldn’t get into Studio 54.

ARAKI I remember you telling me that you were at the first Sex Pistols concert.

WATERS I saw the Sex Pistols in Manchester in London. Somebody took me before they even came to America—before I'd ever heard of punk. And when I saw them, I thought, oh my god. Divine saw the punk girl, Jordan—with her spikes and everything—and said he felt like Plain Jane for the first time ever.

ARAKI As I said, you were literally always at the right place—the epicenter of everything.

JOHN WATERS And now here we are, Gregg. Who would have ever thought that we would be together talking about being in the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures?

ARAKI It's fucking nuts, right? (laughs)

WATERS (laughs) It gives hope to everybody.

ARAKI It's like when I got into Cannes for the first time—I was in The Directors' Fortnight with Smiley Face (2007) and then Cannes proper for Kaboom (2010). If you're around long enough, eventually they open the doors.

WATERS Cannes was always great to me too. Are you kidding? They always like nutcase American film directors. The only thing I could think of that's up there for me along with this Academy Museum show was when I was on the jury at Cannes with Jeanne Moreau. Now how did that ever happen? That was pretty amazing.

ARAKI Were you on the real jury?

WATERS Yeah. The competition jury.

ARAKI Jesus. That’s crazy.

WATERS Yeah. It was exciting. Black tie every night. Being with Jeanne Moreau, who chain-smoked and had a hundred pairs of sunglasses, I said, “It’s so sad that [Michelangelo] Antonioni can't talk anymore.” And she said, “Why? He never said anything anyway.”

ARAKI That's fucking hilarious. So, we should talk about your grand exhibition opening in the fall?

WATERS My directorial exhibition.

ARAKI Wait, directorial?

WATERS It’s really everything about my movies. It has nothing to do with anything else. And they've been working on it for three years. Everything they got from film archives, and they went, and found every crew member, props, handwritten things, costumes, everything. It's really exciting though, and I get to see it before I'm dead. It's really good.

ARAKI So, there’s nothing from your personal collection?

WATERS No, it has nothing to do with my artwork at all. I don't have one thing in my house about my movies. There's nothing in my career hanging around. There are some things in my office, but most of it is at the Cinema Archives at Wesleyan, which started in the 80s. So, it's the most glamorous storage ever. They also have Clint Eastwood, Martin Scorsese, and Ingrid Bergman’s archives. I met Clint Eastwood there and I said, “Just think, Divine's fake pubic hair will be next to Dirty Harry's badge.” And he was really great about it and laughed and everything.

ARAKI So, who's curating it then?

WATERS Dara Jaffe and Jenny He have spent three years on this. There's a beautiful catalog. There’s lots of stuff going on with it. So, they've been everywhere. They've done an absolutely amazing job. They know more about me than I do.

ARAKI I haven't seen you for a while. When was the last time I saw you?

WATERS I don't know, but I was looking through my research about you, and I love the fact that Roger Ebert was mean to you too. He used to do these horrible reviews, and then say to me, “Hi, John! Would you do my panel?” And I thought, “I’m a professional, but am I a masochist?” And I did it, because he did one great thing, he wrote Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), which is one of the best satires that was ever known to man! And he wrote that because he likes big tits! But thinking of that “thumbs up” and “thumbs down,” how tired was that? I was nice to him always, and he was always so mean to me, and I was happy to see he was mean to you too. (laughs)

ARAKI Well, was he ever a fan of anything?

WATERS No! He wrote once about Pink Flamingos, kind of like, it wasn't for him, but it was recognizing its power. But then, he wrote mean stuff about it over and over every other time. I don't remember if he ever gave us a good review, but especially in all my Hollywood movies, he was really mean. And then, I'd see him and he’d go, “Hi, John!” We were very nice to each other and everything, but that is being a pro.

ARAKI It's part of Hollywood.

WATERS I was never angry. I was treated fairly my whole life in Hollywood. I love that documentary—when Janice Joplin, after she became a star, went back to her high school reunion because they were so mean to her. They were still mean to her, even though she was famous. (laughs) So that’s the thing, don't go back to your high school reunion. I've never been to mine once.

ARAKI But wait, were you in the book? Doom Generation was in his book, I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie (2000), which was his list of the worst movies ever made. Were you in that book too?

WATERS But at least we weren't on the most mediocre list. I love being the worst and the best. It's the middle I've always had trouble with my whole life.

ARAKI Well, I told you he loved Mysterious Skin (2004). It was so crazy. His review was literally like I had never directed anything before. He didn't mention anything I'd ever done before.

WATERS Is that the only novel you actually adapted?

ARAKI It's the only novel, Yeah.

WATERS So, do you think he liked it because it was based on a novel?

ARAKI Mysterious Skin was a weird movie because a lot of people who hate me, love that movie (laughs). It was kind of like the movie that everybody loves because it was about such a serious subject matter. But it's funny, when I made it, I really thought it was going to be the end of my career. I really thought this movie was just so out there—I mean, I've always been so polarizing—but I thought people were going to run me out of town.

WATERS But then, didn't you always think all your films would be hits? I did. I was always amazed when they weren't (laughs). I always wanted them to be. I never thought: I’m making this arty little weird movie.

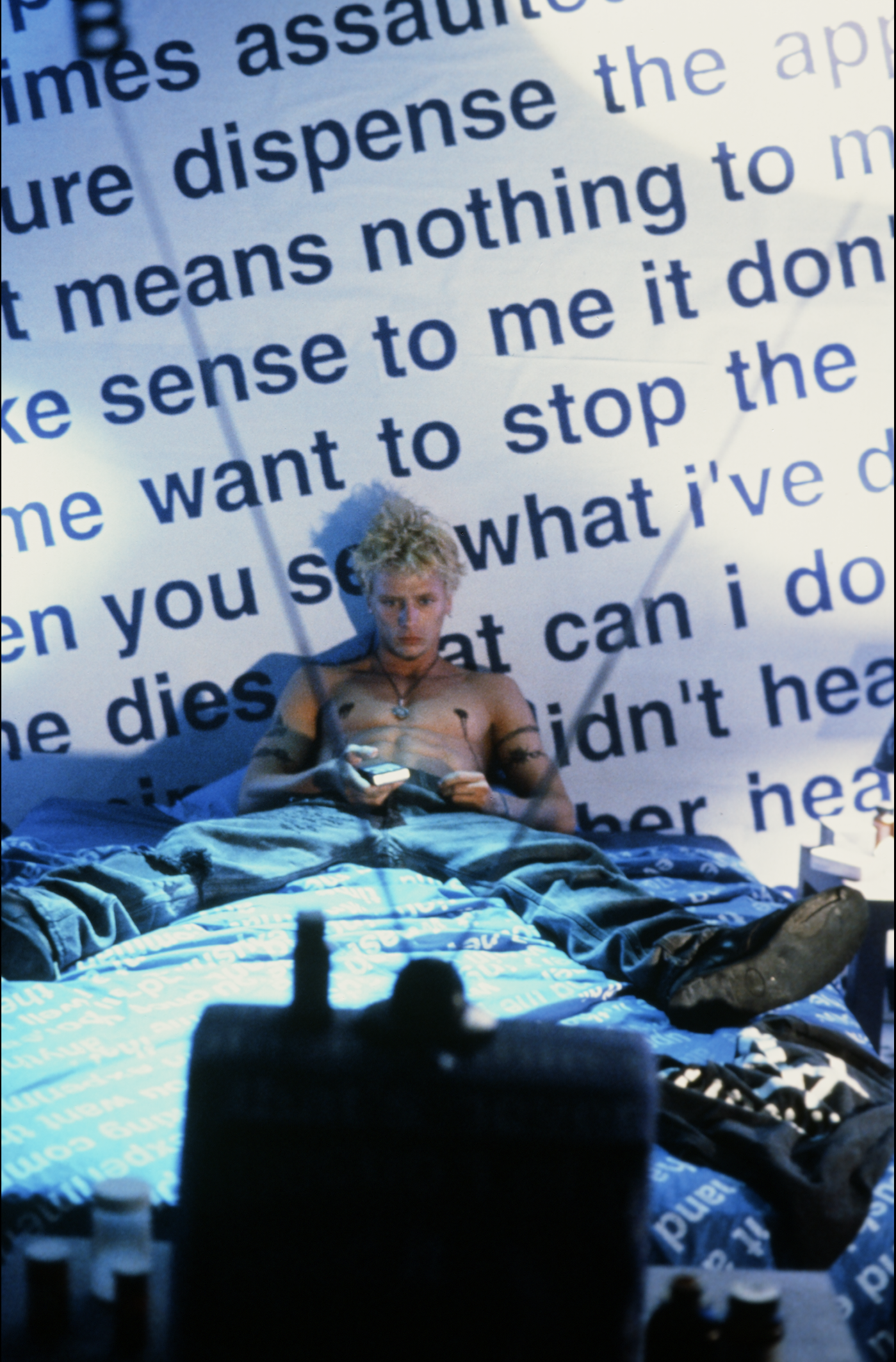

ARAKI When we were touring with the revival of Doom Generation, I told the audience, it's just so meaningful to me and James [Duval] that the love for this movie exists twenty-eight years later, you know? We always loved this movie—this little queer fuckin’ underground crazy movie. But it's like the idea that other people love it and they keep the fire burning for it for decades.

WATERS And it’s no old hat to the next generation, which usually things are.

ARAKI It's amazing. It’s definitely what keeps us going: the idea that we just march to our own drummer, and do our own thing. And you know, I think you have to be a little bit crazy to be a filmmaker.

WATERS I knew about you from the gay punk scene. That's how I first knew about you. And I feel the most comfortable in the punk world. Those are my people because there are ten good queers there that I like. And they're always on the down low in the punk world anyway. When I first saw your films, you were one of the first “gay is not enough” filmmakers who I really like.

ARAKI I told you that's where the Doom Generation came from. The producer, Jim Stark, came up to me and said, “If you can make me a heterosexual movie, I'll get you a million dollars in financing for it.” The Living End (1992) and Totally Fucked Up (1993) were made for twenty grand or whatever. So, he was like, “You make these gay movies that gay people hate (laughs). They're too punk for gay people. If you do a heterosexual movie, I'll get you a real budget for it.” I remember The Living End, especially, was triggering for so many gay people. And I wrote Doom Generation in my sort of punky way of making it the queerest heterosexual movie ever with this really exaggerated queer subtext to it.

WATERS But now, it's so different. There’s that really cute DJ Diplo that said, “Well, I’m not not gay.” And because you had a girlfriend that you got a lot of shit about, you can say, “I'm not not straight.”

ARAKI (laughs) Yeah. And when I was dating a woman in the mid-90s…

WATERS It was so hilarious that you got shit—I gave you so much shit.

ARAKI You said, “He just went in.” (laughs)

WATERS That was the most radical thing you can do. And I keep saying, “What stunt am I going to do for my 80th birthday?” I hitchhiked across the country in my sixties. I took acid in my seventies. Maybe I’ll turn straight in my eighties.

ARAKI That was probably one of the most scandalous things ever because I had been known as this Queer New Wave filmmaker. And I remember being on the Sundance jury in 1996—I was there with Kathleen [Robertson], and we were stupid, and young, and in love, and were making out at every party. People’s jaws were literally dropping. It was crazy.

WATERS (laughs) I think it's great because people give you shit about it, which really makes me laugh that you can come out of the closet, but can you go in and out, in and out? Can't it be a revolving door? You're lucky. Everybody's cute. I wish I was bisexual. But I'm interested in what the young people are doing. As soon as you say, “Oh, we had more fun [than today’s youth] when we were young,” that means you're an old fart and don't matter anymore (laughs). Because they're having just as much fun right now.

ARAKI Are they?

WATERS Yeah, they are. Oh yeah.

ARAKI I hope so.

WATERS They're having just as much fun and they're scandalizing us with a new sexual revolution.

ARAKI I hope you're right. I am actually concerned about the newer generation in the sense that they aren't having sex anymore. There’s too much social media and texting.

WATERS They don't have any parts anymore to have sex with! They can't figure out where it goes, which is real anarchy. Like, you go home with somebody now, they take off their clothes, and you have no idea what's going to be underneath there.

ARAKI (Laughs) Yeah. I love that. It's really interesting when we've been doing these Doom Generation screenings, I just expect it to be a nostalgia trip, but at least half the audience, sometimes 85%, is all young people.

WATERS I know. Me too. That's great, Gregg, do you know how hard that is to get?

ARAKI It's amazing to me.

WATERS No, it's the ultimate compliment.

ARAKI Like, how do you even know about this movie? You weren't even born! Your parents weren’t born.

WATERS (Laughs) They weren't born when I made my last movie, much less the first one. I just did a tour in Paris for my book, and little 20-year-old French kids gave me poetry books they had written about me. It was amazing and incredibly exciting. If you're a director, you always have to go with your movies. You have to meet the ticket buyers. I always believe you have to be out there involved in the selling of it. I know you don't like to travel, but I have a fear of not flying.

ARAKI Yeah, I know we've talked about that. I'm not a big traveler, but I do it. But you're afraid to not be touring everywhere.

WATERS I am. Because Elton John told me, and it's true, “Once you stop touring, it's over.” And you can't blink either, because somebody's ready to steal your place, Gregg! Remember that—somebody in LA is trying to steal your place.

ARAKI But didn't Elton John just stop touring?

WATERS Yeah, but he didn't say he was never performing again. He just wasn’t going to do 150 shows a year. (laughs) Do you know who tours the most? My idol, the mentalist, The Amazing Kreskin. He plays 300 nightclub gigs a year, and he must be 85. I have him in my book under A. I just call him Amazing. What a great career.

ARAKI Did you see the Joan Rivers documentary? That’s how she was too.

WATERS I think either one of us, wherever we had been born or lived, we would do the same thing. We would kind of glorify what's going on in the city that some people are against. We would praise what others put down. LA is very much a character in your movies, but in a good way, in an exciting way. You're not going to meet the cheesy sitcom stars, or if you are, something bad happens to 'em. And the characters are always sexy. People jerk off to Gregg's movies, nobody jerks off to mine. And I think that's important, Gregg. I honor you for that.

ARAKI (laughs) I remember when Now Apocalypse (2019), my Starz show premiered, somebody took a screencap of them watching the show on an iPad and jerking off at the same time. (laughs)

WATERS I had the guy with a singing asshole—who's a straight guy by the way—tell me it was a yoga exercise and he said, “Would you like me to audition?” I said, “I believe you. No, that's okay.”

ARAKI (laughs) But yeah, it's very true that Los Angeles is a huge part of my movies and a huge inspiration for me. I remember when I was in film school somebody said to me, “Living in LA is like being inside a giant cartoon.” You know what I mean? And that's why I love it here, that it's so surreal and you just see the craziest shit. One of the things I love about LA is people just don't care. You can walk around naked with a chicken head on and people won't blink twice because it's LA. Whereas in Santa Barbara, or Goleta where I was born, which is a suburb of Santa Barbara, if you have an earring or something and walk into a restaurant, people stare at you. You hate it here because it's the center of Hollywood.

WATERS I don't hate it because it's the center of Hollywood. I hate it because it's suburban. I don't hate LA. I have some of my greatest friends there. When things are going well, LA is so fabulous. When they aren't, it can be terrible for me. When things go bad in your career, it's kind of the worst place for me to be. In Baltimore, no one's in show business that much. I have trouble in LA ever meeting anybody that isn't in show business. But I've had some of the best times in my life in LA. My movies do well there. You can read my book, Mr. Know-It-All (2019): I'm not bitter about one thing. Hollywood treated me fairly from the beginning to the end. I climbed my way to the top and climbed right back down.

ARAKI But the question is, did you treat Hollywood fairly? (laughs)

WATERS No! They'd say. Because the executives that greenlit my movies—they liked them twenty years later, but they didn't make money then, and they got fired. They don't care if people like it twenty years later; they get to greenlight three movies a year and they better be hits.

ARAKI Did you self-finance your first movies or how did you make your first movie?

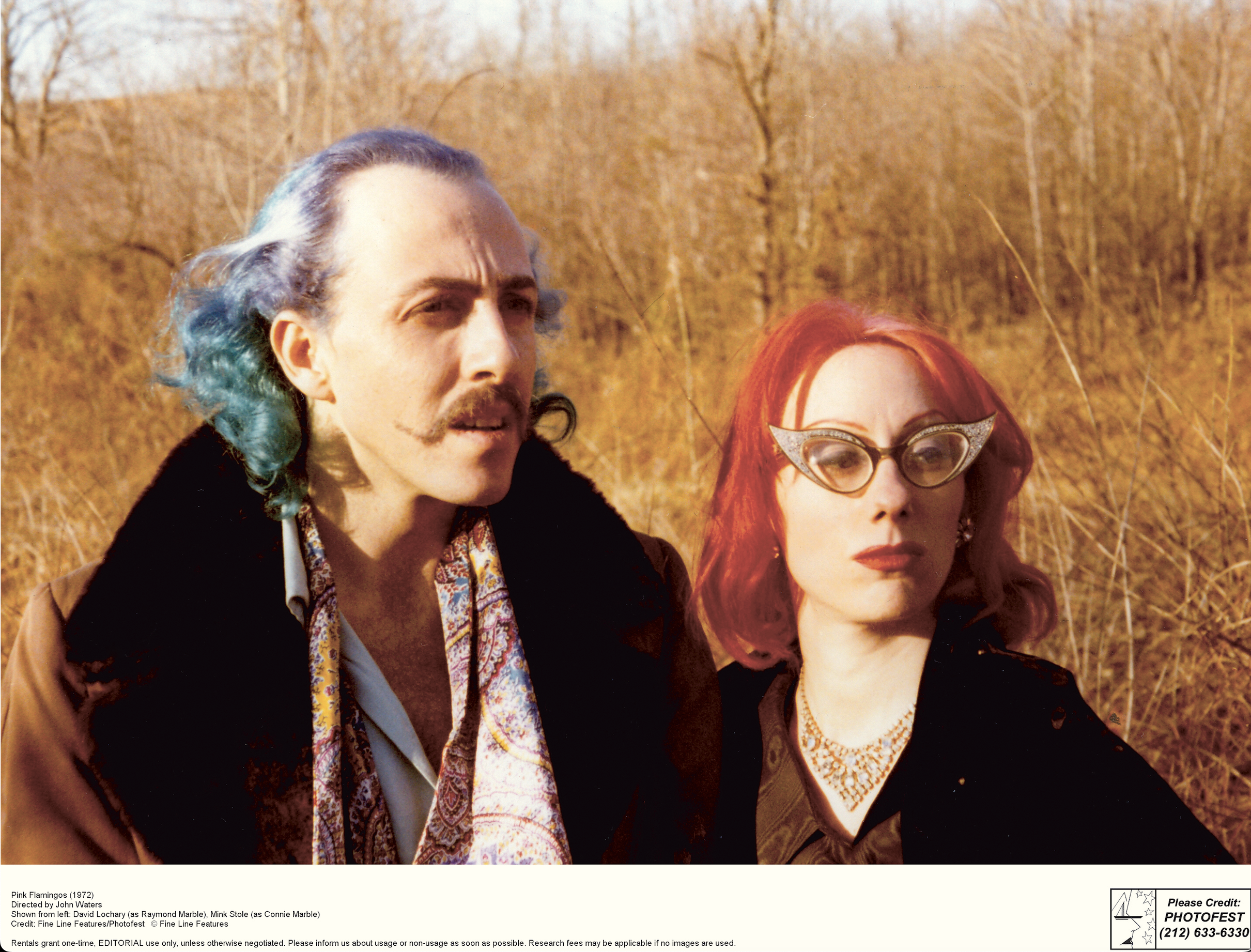

WATERS Well, I borrowed it. I raised the money all the way up to Polyester (1981). I raised the money and paid everybody back. So everybody that I ever knew personally got their money back from me and still gets their money. Even when they die, I give their kids money. The studios didn't always pay them back. Luckily, I own Pink Flamingos. I own all my movies up until Polyester. But who would ever imagine that Warner Brothers would be the distributor of Desperate Living (1970)? Who would have ever thought that Janus Films would distribute Multiple Maniacs (1970)? I used to see the Janus Films logo ahead of [Ingmar] Bergman and [François] Truffaut films.

ARAKI That's where you belong, you know, in Criterion and Janus Films along with the Battleship Potemkin (1925).

WATERS When I was starting with Fine Line, which was the arty part of New Line, they made up Saliva Films, which I hated. That was to avoid police prosecution for Pink Flamingos.

ARAKI As I said, you kind of have to be a little bit crazy to be a filmmaker or an interesting filmmaker. You really just have to believe in what your vision is.

WATERS I didn't have any idea what I was doing! You went to film school. The first movie I made was Hag in a Black Leather Jacket (1964). It's very Dogma 95 without realizing it. I didn't know there was editing. I just shot each scene of the movie in order and that was the movie.

ARAKI (laughs) You have to believe in your own voice. I just have a very myopic view of what I do. I collaborate, I listen to people, and I listen to the DP or actors, if someone has an idea or something, but for the most part, I just have a vision. It’s almost like a mental illness; it’s like, yeah, this is what I'm gonna do.

WATERS Exactly. That's the only way anybody gets their first movie made. You don't even consider that you can't make this movie. People say later, “Did you have fun making that movie?.” Fun? Fun is when it's a hit and you're having a drink two years later. Fun? Being outside for those early movies—outside for twenty-hour days—you want something to eat? Go into the woods, find it, kill it, and cook it.

ARAKI I have to say, in retrospect, I had fun. I have super fond memories.

WATERS I'm proud of it in retrospect, but not fun. Like, haha, lalala, isn't this fun?

ARAKI In the moment, I'm not having fun. Because it's so stressful. It's so much work and you're just so focused, but in retrospect, I look back on it as a really warm memory. I mean, we're lucky, we've gotten to make a handful of movies. And each one, they're like my kids.

WATERS Yeah, and you can't pick your favorite. I always like the one that did the worst. You have to just stick up for the one that has a problem.

ARAKI (laughs) You like the one that's neglected, you know what I mean? Like the real popular one, the one that's super successful, it's just like, oh yeah, that one. But then, there's the one that has the problems.

WATERS Yours are very different. To me, all my movies are sort of exactly the same. They have one moral: don't judge other people, make the people you don’t agree with laugh, and then they'll listen.

ARAKI Is that the overriding theme? The overriding themes are not that different for my movies then, I would say.

WATERS No, I disagree. Your movies have the same joy in it. What you're saying is that people who don't rebel by the time they're twenty, usually have a very dull life. The prom queens and the football stars, it's downhill from the day they graduate. It really is. You see them later and you think, oh my god. I’m also against homeschooling. I think that's crazy too. You have to learn how to get through it. That's how you learn to do everything. And I always used humor. The people that would have beat me up didn't, because I could make them laugh at authority, which made me safe. You can't tell your children to just go make fun of the teachers and the kids won't beat you up. But it does work.

ARAKI Well, neither of us has real kids. We just have celluloid kids.

WATERS I like kids. And they come over to me now because I was in the Alvin and the Chipmunks movie. I look like a child molester, so it's awkward in airports. But if we had to make our movies today, I guess we’d have an intimacy expert telling Divine that it's okay to be fucked by a lobster. (laughs)

ARAKI You'd have an intimacy coordinator telling the guy with the singing asshole that it’s okay.

WATERS Divine would drink her own urine rather than eat dog shit in a more Hindu, kind of politically correct, way.

ARAKI I don't think my films would change really at all. The only issue is social media. When I made my TV show in 2018, one of the issues is so much of the fucking movie is texting, and on a device—so many inserts of texting.

WATERS That's a whole other third unit.

ARAKI Story-wise, and script-wise, it's such a pain in the ass. I'm working on one thing now and I'm just setting it in the 90s, so you don't have to deal with that device.

WATERS Even though I was a chain-smoker, I never had anybody smoke cigarettes in my movies because of continuity problems. If you ever wanted to cut to make a scene shorter, then their cigarette is half-smoked in one second. Or don’t have people yawn in a movie, because then the audience does, or look at their watch. If people are yawning or looking at their watch while they're watching your movie, that means it's boring.

ARAKI Those are good rules. You should put those in a rule book.

WATERS Also, don't ever say the word “cult” in Hollywood when you’re trying to raise money. That means ten smart people liked it and you’ve lost the entire budget. My advice is to go see every movie. Watch it without the sound and you can really tell how it's made and see the ones that work and what didn't work. Read Variety every day—you have to learn the business and see everything. And two people have to like it besides the person you're fucking and your mother.

ARAKI I'm taking that advice.

WATERS And if you ever think you should cut a scene, you should because all movies are too long.

ARAKI I’m currently remastering Doom Generation, again, re-mastering Nowhere—both those movies are like 82, or 83 minutes.

WATERS That's perfect.

ARAKI Remember, John, this isn't the first time we met. I remember winning the Filmmaker on the Edge Award at Provincetown for Mysterious Skin, in like 2004. And you presented the award. Backstage you were like, “Oh, you know, Mysterious Skin is great, but I really miss the old-school Gregg Araki movies.” Kaboom was one of the ideas I was working on at that time and that comment was just lodged in my brain. And Kaboom was very much inspired by what you said to me.

WATERS Oh, don’t pay attention to anything I say. Take it like a bad note from the studio.

ARAKI Kaboom is all my themes and motifs—almost like my greatest hits, like every movie I've ever done—rolled up into one.

WATERS Are your parents alive?

ARAKI Yes, both of them.

WATERS Have you sat with them and watched your movies?

ARAKI I have not. Particularly with The Living End, I was like, do NOT see this movie.

WATERS Me too, but then they feel like they have to.

ARAKI My family is super supportive and they've always supported me, and it’s amazing.

WATERS Mine too, but my father once said, “It was fun. I hope I never see it again.” And that was the best blurb.

ARAKI One time my parents actually drove to Los Angeles and watched The Living End at the The Regent Showcase on La Brea. It was a matinee screening. I told them specifically not to watch it. And the theater manager told my mom, “Ma'am, I think you're in the wrong theater.” (laughs) My mom told him, “No, no, I wanna see it.” Thinking about my parents watching my movies, I could never make my movies. You know what I mean?

WATERS The reason people like our movies is because they know their own parents would be horrified.

ARAKI It's a parent-free zone, you know, and you could just express all the craziest shit you want.

WATERS I filmed Multiple Maniacs on my parent's front lawn. You know, “the cavalcade of perversion!” They were very accepting. They were horrified, but I think they figured, what else could I do? Really? What else could I do? Hag In A Black Leather Jacket. For that movie, my grandmother gave me the camera.

ARAKI Was it a Bolex?

WATERS No, it was a little Brownie! A Bolex, are you kidding? This was a little Brownie—an 8mm camera. And I shot it on the roof of my parent's house. It's a Ku Klux Klan man marrying a white woman and a black man. I don't know what I was thinking about, but it was very influenced by the Theatre of the Ridiculous at the time. That's what I would say was the big influence. It was 15 minutes long and it showed once in a beatnik coffee house.

ARAKI Do kids have that now?

WATERS Well, it would be online, it would be on the phone. It's a whole different way. We don't care, you know, phones look better. You can't see the mistakes (laughs). Who wants to see Hag In A Black Leather Jacket in 70mm? You know? I guess that would be a new experience.

ARAKI Or IMAX.

WATERS Yeah, exactly. I saw Jackass in IMAX, the last one, and I never saw someone's balls that big in pain on a screen. Well, it was great talking to you, Gregg. I'll see you at the Academy Museum this fall. I'll see you at dinner.

ARAKI Thank you, John, for doing this. I know you're so busy.

WATERS All right. Toodle-oo.