text by Abbey Meaker

“Nothing distinguishes memories from ordinary moments, only later do they make themselves known, from their scars.” ― Chris Marker

What if instincts are actually descendents of memories? Memories are fragmented downloads of experiences–impressions, the essence of things seen, felt, endured. My father’s roses, the grass my mom planted over his garden–its smell, light through trees animated by the wind, the transporting song of a mourning dove. These interior recordings create invisible, connective chords, memory material. We come in with genetically encoded instincts; some may be translated memories of our parents, grandparents, great grandparents, etcetera. They too were linked by invisible chords, to each other and beyond. This ‘memory material’ creates an ever expanding web of desire and drives that evolve through our own becoming.

Some of these instincts may be innate, raw materials, while others are profoundly individual, organic. In one person, suffering will create a prison and in another, liberation. Perhaps it is the soul, the unknowable thing which pushes us through time with a deep sense of knowing: material folding and unfolding. I would argue that the function of cinema is to explore these sense impressions, the murk of our desires. Film is exploration, rehabilitation, salvation; it uncovers what is concealed, brings to life the unseen, those invisible chords by which we are connected to infinite worlds.

The visionary artist and filmmaker, Sir Steve McQueen, has mastered storytelling beyond the limitations of language. Like feeling your way through a dark room, the experience of watching a Steve McQueen film is completely and viscerally experiential. McQueen forces us to see with all of our senses. He directs and holds our gaze upon what seem like banal moments; however it is in these scenes that we find the essence of not only the film but of that mysterious invisible thing that guides and connects us: a light flickering upon the intangible, the invisible web of us. The depths of experience in being human. Through this durational observation, a scene from a movie becomes pregnant with meaning, like a photograph in which you continue to find new information, greater depths. McQueen assigns a moment to our memory, keeps the camera rolling, elongating a moment for what feels like too long. There is a thought process that unfolds: why am I still looking at this? When will the next scene begin? There is an instinct to look away, but we are forced to keep looking until we’ve had adequate time to contend with what we have seen and felt.

Many of McQueen’s films are historical, and always about the individual, conflicted figures, their depth, interiority, the dynamics of relationships: that of families, lovers, friends, a political prisoner and his priest. Within the larger context of these stories and their historical significance are intricate, raw depictions of people and relationships, and the richness and complexities of in-between moments. We are asked to actively consider horrific truths of both the past and the present, where we come from and where we are now, what connects us in our humanness, where we have and continue to falter. McQueen deals with specific historical events as well as universal themes, particularly concerning loss, self reckoning, and liberation: political prisoner Bobby Sands and the Hunger Strikes in 1980s Northern Ireland (Hunger, 2008); the story of Solomon Northup, a free black man from upstate New York, who was kidnapped and sold into slavery in the South (12 Years a Slave, 2013); Frank Crichlow’s Mangrove restaurant in west London, and the trial of the Mangrove Nine in 1970 (Mangrove, 2020).

“Mangrove”, from the Small Axe series, is an historical drama about the Mangrove restaurant in west London, opened in 1968 by Frank Crichlow, a Trinidadian immigrant. The restaurant was a sanctuary, an integral meeting space for the black community in the Notting Hill neighborhood, particularly for black activists, artists, and intellectuals. In the restaurant, McQueen has created a warm, immersive environment; it vibrates with atmosphere and life. Music is always playing and patrons are engaged in lively conversation, floating in and out of the space, signaling a feeling of safety, community, and home beyond the restaurant's physical borders. Crichlow is faced with relentless, violent, and baseless police raids led by sadistic office Frank Pulley. The film jumps between the vibrant warmth of the Mangrove and the stark, cold monochrome of the police station: the life-giving glow of the sun, burning and suspended in vast, cold space. The police see the Mangrove as a transgression, a threat to the white British way. After a particularly violent sequence in the restaurant, a colander is knocked off its base. In a lingering shot, the camera traces the chaotic violence down to the kitchen floor where that colander aggressively rocks to its final rest. The plea to keep looking when the instinct is to look away from violence is challenging but comes with its rewards. The rocking colander lulls the viewer through conflicting emotions: the desire to get through the scene, to skip over what has happened, engenders a kind of reckoning. We are forced to process what we’ve just seen before moving on.

The harassment of the police forced Crichlow into becoming an activist. In response, on August 9, 1970, the black community organized a march in which 150 people protested police conduct. The police again provoked violence, and a number of the protestors were arrested and charged: Frank Crichlow, activist Barbara Beese, Triniadian Black Panther lead Altheia Jones-LeCointe, Trinidadian activist Darcus Howe, Rhodan Gordon, Anthony Carlisle Innis, Rothwell Kentish, Rupert Boyce, and Godfrey Millett. Their trial lasted 55 days, and though not all of the charges against the Mangrove Nine were acquitted, the trial became the first judicial acknowledgment of behavior motivated by racial hatred within the metropolitan police. It was a critical case in the British Civil Rights movement. For many children, “Mangrove” has created a connection to a time their parents may not have talked much about but that likely influenced their relationships. The present is imbued with sense impressions–wounds–of the past.

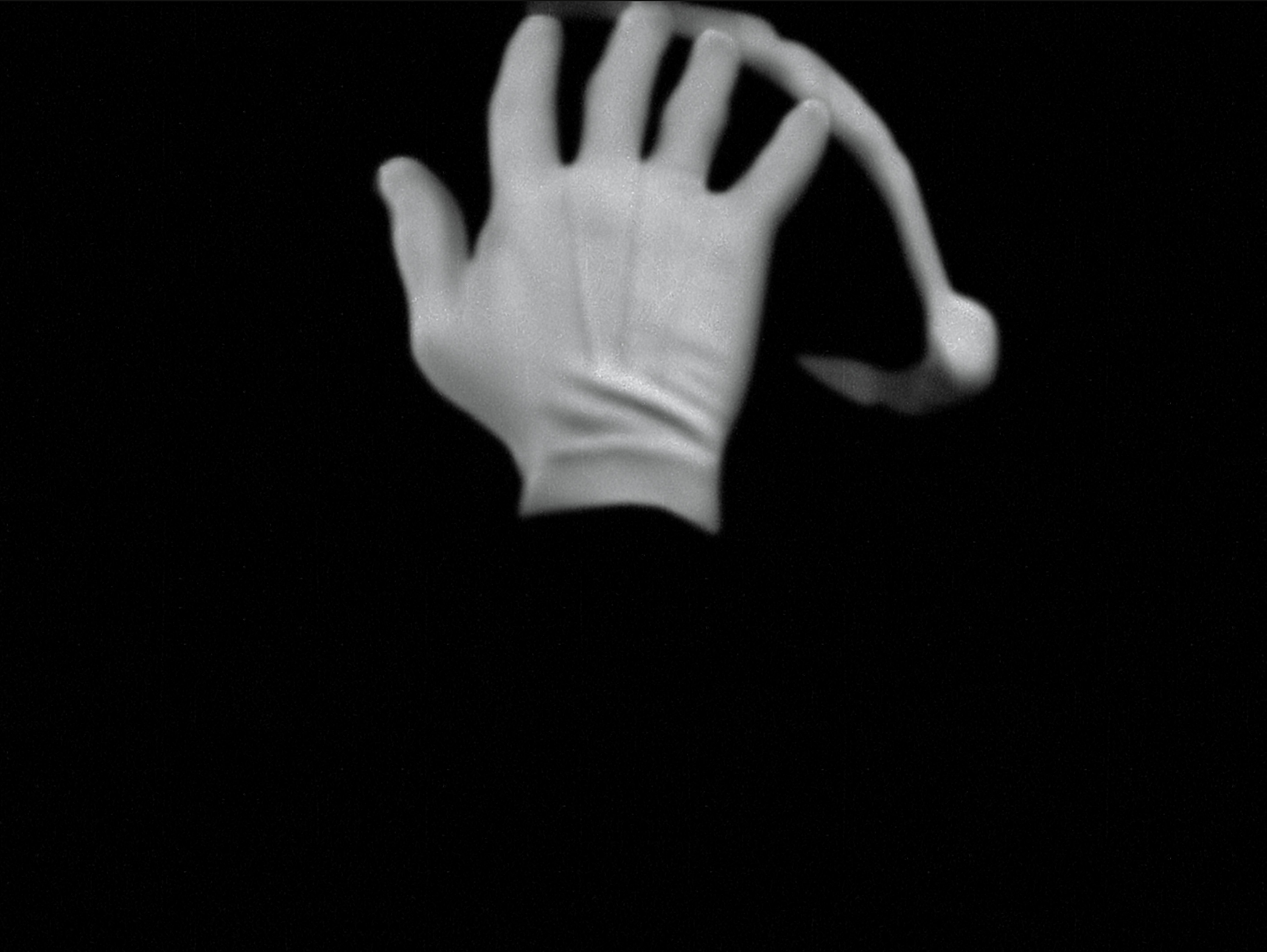

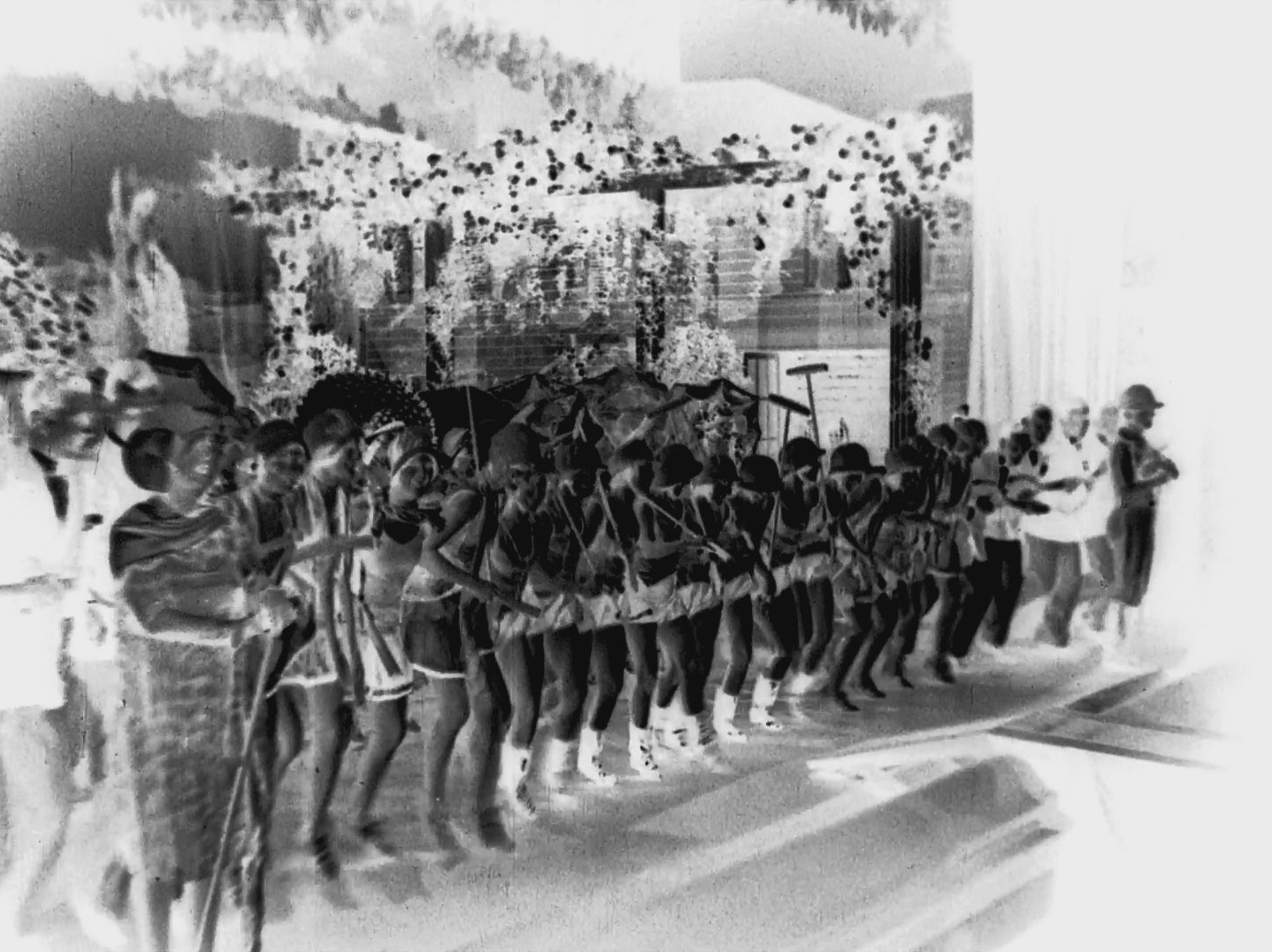

Steve McQueen’s latest artwork, Sunshine State, is weighted, ripe with memory material. In the two-channel video installation, projected on both sides of two screens, one placed beside the other, McQueen weaves the deeply personal with the historical. The work opens with footage of a burning sun and unfolds into scenes from the 1927 film The Jazz Singer, a musical drama and first feature length film with synchronized dialogue, the first “talkie.” The film stars actor and singer Al Jolsen who is shown applying blackface makeup in preparation of a Broadway dress rehearsal. Against a black backdrop, the blackface is never actually shown. In McQueen’s version, only Jolsen’s suit and white minstrel gloves can be seen. The rest disappears; he becomes invisible. Juxtaposed with the black and white images of the Jazz Singer are video fragments of the blazing orange sun, a burning, breathing neon orb. Over the video is McQueen’s voice recounting a devastating story his father shared with him just before his death. The story is told in full, then repeated until fragmented, distorted. It is a life transforming story, like a door to a dark room opening to the sun. His father was taken from the West Indies to work picking oranges in Florida, where a casual visit to a bar after work ended in traumatizing fatal violence.

It’s impossible to know to what degree this unknown experience, its memory, its wound, has informed McQueen’s art practice, but he has largely uncovered and shown a light on stories and people who were unseen, ignored, erased. There is liberation in being witnessed, in being seen, and through observing and absorbing, the invisible chords that connect us are fortified. His father’s final words, “hold me tight,” are recited as a chant, a mantra to the sun burning on in a vast dark space. In an interview, McQueen asks himself what he discovered looking back on the years-long process of creating “Sunshine State”: “I suppose I was carrying shit with me…heavy shit, and I didn’t know I was carrying it. I think that weight is what I discovered, of what you carry with you, and I don't know if I’m lighter, but I’m more appreciative.”