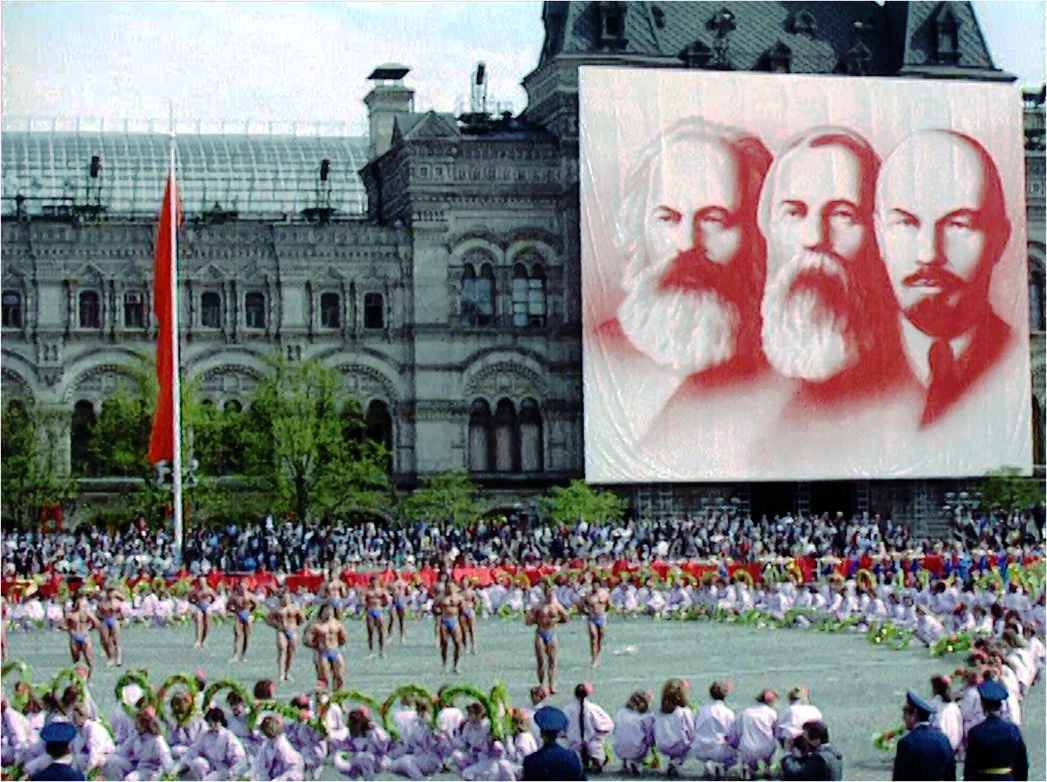

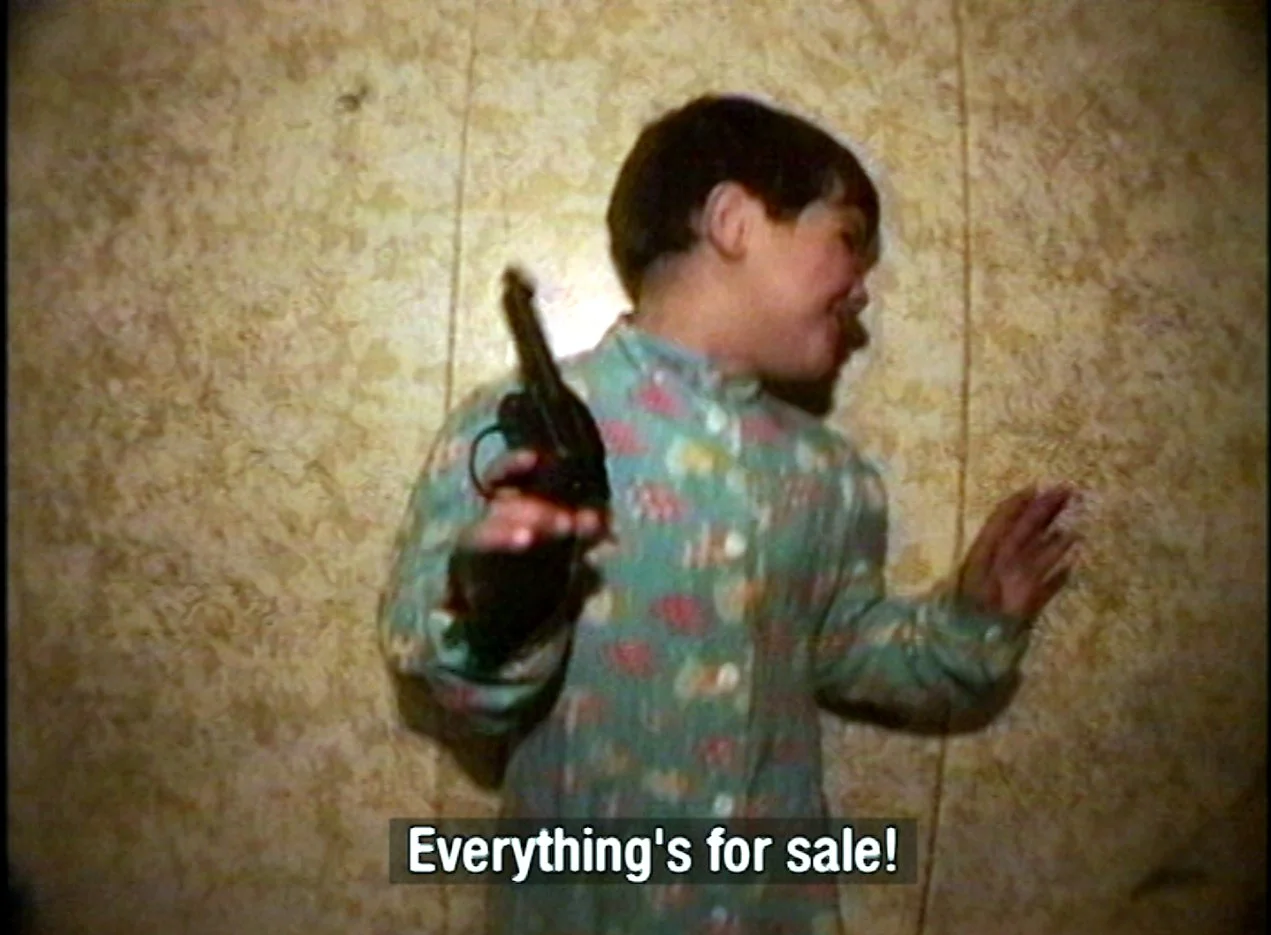

For nearly forty years, the documentaries of elusive BBC journalist Adam Curtis have told us fascinating, complex stories about power and disillusionment—particularly the disenchantment caused by the fables we tell ourselves to make sense of a violent and chaotic world. His narration is instantly recognizable in films like Century Of The Self (2005), about Freud’s theories of the unconscious mind and how PR machines used them to manipulate mass populations of contemporary society, or HyperNormalization (2016), about how we got to our present post-truth zeitgeist. His most recent film, Russia 1985–1999: TraumaZone (2022), encapsulates these ideas. Told through a dizzying array of found footage, the documentary features the collapse of both communism and democracy and the rise of a corrupt group of oligarchs who placed Vladimir Putin in power for financial gain. Last year, Curtis tapped into his vast trove of video archives to create the concert visuals for Weyes Blood (the moniker of critically recognized American musician Natalie Mering) to support her 2023 album And In The Darkness, Hearts Aglow. He also created the music video for the single, God Turn Me Into A Flower, a poignant track about the myth of Narcissus, but also our eternal fall into the black mirror of a technology-obsessed world.

ADAM CURTIS I think the reason you and I got on was because we share the same interest in what happened to that optimism of individualism and to what extent it was retreating. What I liked about the song [God Turn Me Into A Flower] was that while it was about the retreat from that optimism, it also has a sort of optimism of its own. I thought that was very unusual in modern culture. The thing with the doom loop vibe at the moment is that there very much is a sense that there's nothing else.

NATALIE MERING There are many parallels between what we're doing to the planet and what we do to ourselves. When I first read the actual myth of Narcissus, I was so amazed that our culture had notoriously misinterpreted it. Everybody thinks of it as this person who’s obsessed with their own reflection; wasting away in their vanity. But the real crux of the myth is that he doesn't recognize the reflection as himself. He thinks of it as this otherness. In our culture, everybody is seeking external validations and identities to be happy. If I had that, or if I had this—there's always this postponement of experiencing reality. There are so many different ways that this applies to modern consumer culture and the inability to witness ourselves within nature.

CURTIS The idea of being truly yourself now depends totally on the idea that you are being watched. If you have ever seen Paris Is Burning (1990), marginalized groups—gay, Latinx, and Black—know that they have absolutely no chance of getting into the mainstream of society, so they decide to act it out. They act out being business people, or they act out being heads of the army, and they do it absolutely perfectly. They created what they called ‘realness.’ What's intriguing about it is that, in a way, that's what everyone does now. Everyone pretends to be something, but it only works if you feel you are being watched. If you don't feel you are being watched, you're not real. That's the paranoia at the heart of our society. That sense of believing in yourself as yourself has disappeared, or receded even further.

MERING Generationally, the difference is having principles. Because there was no social media for Gen X or previous generations, whatever you did in person, or whatever you did in action, or in relationships, that was an advertisement for your persona. Now, I feel like people can create a persona online and not actually have to live by those principles in reality. It's such a perfect platform for performance.

CURTIS It's also because that system was created by engineers and engineers work on the basis of feedback. So, you're always being fed back information about yourself. And therefore, you begin to perform. I think it's inevitable. The really interesting question is what, then, happens to the real self? It sort of disappears. We live in this incredibly emotional age, but the paradox is that what you're seeing is a performing dramatic self.

MERING As a performer, this is a very interesting and very confusing topic for me. Sometimes the way I feel, which I can imagine could be applied to a lot of people in generations that are very influenced by technology, is like a huge sail. And when there's wind, you're open and you're feeling okay; I'm serving a purpose. But when there’s no wind, a sail is this weird, crumpled, empty, flat, flabby thing. It's a very intense feeling for me to come off-stage and feel all that deflation. The first thing I feel is a weird disassociation. If I’m just this floppy, empty sail, what is the ultimate purpose of what I'm doing? This is really personal to admit, but I can imagine that if a lot of people were stripped of their phones and the opportunity to feel the wind fill their sail, they would feel like, what is the shape of this person that I've become?

CURTIS That's exactly right. But what you’re doing, it's real. The tragedy for most people is that they inflate that sail and they don't know why. They just hope that people are watching, which is quite tragic. At least you're in a venue, and you can see them, and you can feel their reaction. What we used to do—and this is true in religion, and in wider parts of society—is that we used to have a private self and a public self. In the 19th century, and actually way up until the 1950s, people would have their public persona that they would go out and perform. For instance, a self-confident Englishman. But then, you went home, and you were someone else. You had your private world, you had your friends, and the two were distinct. And then, somewhere, way before the internet came along, the ‘authentic individual’ took over, meaning all those elements—both the public and the private—must be authentic. I think that confused a lot of people because a new question arose: Am I being authentic in private, or am I always acting?

MERING I forget who said this quote, but it was something like, “If we could collect all of our subconscious impulses into a basket and make art out of it, it would really just be a repetition of advertisements.” At this point, our subconscious is so overloaded with ads that, in the end, it's like the subconscious could actually be this kind of garbage pail for the trash of our society. And yet, people would love to believe there's something more awe-inspiring than just biological impulses.

CURTIS I blame Sigmund Freud, myself. He was such a pessimist; he believed that there were these dark things inside us that you'll never get rid of. I've always thought that this idea rather holds us back. I don't disbelieve in the unconscious, but I just think it's not that powerful. And I think, possibly, we fetishize it because we feel weak and unable to actually change ourselves, or change the world for a better purpose. So, we blame it on these dark forces inside us. I don’t know if you've been on TikTok recently, but everyone is talking about trauma.

MERING Trauma is the perfect golden ticket to explaining the discontent of our modern world. People are desperate to understand the more subtle negative impacts of modern consumer culture and what that does to your mental health and your physical body. I'm the first guinea pig generation that grew up eating the most processed food imaginable in America. All this stuff is radically different from my corn-fed boomer parents. I feel like that is another reason why the younger generation is continuously scrubbing their past, looking for reasons why they don't feel how they thought they should feel.

CURTIS When I look at these TikTok things about trauma, I think I'm watching a modern ghost story. It's just people telling me that they're haunted by something inside them all the time. You're really sympathetic. You feel that there's something holding them back. But there are other, wider questions at work, such as: is it possible that the kind of society you are living in is making you feel so bad that you are retreating into yourself? But no one says that. What they say is, “No, it's you. It's your fault.”

MERING I do feel like that kind of pop psychology, self-help, self-diagnosis, “go online, do some reading, and figure things out,” is definitely a huge diversion from confronting the bigger societal structures that contribute to the downfall of community. The isolation, more than anything else, is creating the overall scope of people's reactions. For the most part, people are dealing with these feelings within the vacuum of their algorithm.

CURTIS When we last met, we were talking about how new religious feelings might reemerge in society. The power of religion was to offer people in the past a sense that they were part of something bigger than themselves. There are other ideas of freedom than just individual freedom. We live in a very pessimistic time when people feel that they can't change things. But there were other periods of history where people felt that if they gave themselves up to something, it might change the world and they would be part of something that went on beyond their existence. That's a lost idea at the moment, but I think it might come back.

MERING In America, especially right now, the young people that are against what’s going on in Palestine—I think that is the closest thing I've seen to that kind of unity, that kind of fervor, and the kind of passion to try to do something. The whole idea of self-immolation within this time seems so abstract because most people are just online posting about this stuff. And then, Aaron Bushnell lights himself on fire. That was a big moment for the younger generation; a moment for them to not feel as powerless. It was almost like, okay, somebody did something. We did something. We're not as selfish and distracted as everybody says we are. But I would say, based on the way information is controlled via phones and media, it’s hard to get that kind of grassroots organization. The ’60s or ’70s political activism is lost because our systems of information and communication are completely fielded by tech giants.

CURTIS The ’60s radicals had a politics which had a map to it. It may have been a decaying one, but at least they had a map. What now? There is no alternative map, and there is this real sense—and this is sort of what I'm gonna make some films about—that the map that we are given by older generations no longer describes the territory we're living in or experiencing. And I think that if you are protesting, it's sort of incoherent at the moment. You know what you're against, you know how angry you are, but no one's giving you a map of what you do with it. And it's up to them to come up with that map. But it's really interesting, left and right, it makes no sense any longer.

MERING I call it the culture divorce. There's been a cultural divorce in America. There's so much fighting within each camp that the division isn't as traditional and strong.

CURTIS I was reading a book about the revolutions of 1848; when revolutions rose up everywhere across Europe. The writer of the book, historian Mike Rapport, was arguing that before 1848, the traditional political divisions, which we have grown up with—left and right, the establishment, the idea of what's real—didn't really exist. They were created then. Prior to that, he said, they lived in a hazy and fluxy world. And I think that's where we've gone back to now. We're in a hazy, fluxy world where the sense of the ways you ordered this reality have all dissolved, which gives you people like Trump. I don't think you can blame Trump. He's the ringmaster for this crazy world. What we're waiting for is someone to not be a ringmaster, but to actually give us a map. If you are twenty-five years old now, it's very difficult. But it's also quite exciting.

MERING It's uncharted. I remember very distinctly when I was at Occupy Wall Street. That was a big moment for me because I felt this youthful excitement. And I think the biggest criticism of Occupy was that we couldn’t write a manifesto. There were no actual concrete terms. It’s super random, and you guys are also punk and you're living in tents. I remember thinking, of course, there's no manifesto written because it's not as organized as it used to be and people stopped reading as many books as they used to. The onslaught of the liberal arts education brought on this idea that you don't need to read the classics, so you don't need to have those kinds of skills. You just need to follow your bliss. Now, they're saying that college students are having trouble with reading comprehension.

CURTIS If I was a college freshman, I would argue in retaliation that actually those who are supposed to be telling us what's going on—journalists, politicians, think tank people—seem to have problems comprehending what's going on in the world. I had to give a talk at the American Embassy to a lot of very posh journalists and think tank people. I just said, “Look, people don't trust us any longer because we haven't predicted anything. We didn't predict the financial crash of 2008. We didn't predict Donald Trump. We didn't predict Brexit. We didn't predict the Ukraine war. So, we have problems comprehending the world, and that's why they're turning away from us. It's not just because of the internet.” They got so cross that I thought, Oh, I think I've probably touched on something here. And the reason it’s true is that there is no map.

MERING What do you think of YouTube and the rise of everybody as a journalist?

CURTIS I think that's inevitable. But actually, if you watch those things, they're still trying to pretend to be old-fashioned journalists. They're still working with the old map. What you were talking about with the Occupy movement and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in the middle of the pandemic—it's incoherent and that's why older generations are shocked by it. And, in a way, it's not making sense because there is no map. They're just reacting. There are some very good YouTube journalists actually trying to ask interesting questions, but a lot of it is still trying to imitate mommy and daddy. And that's a bit sad. The information that's passed around in these new venues of journalism tends to actually be created by the original old legacy media. YouTube doesn't have a news-gathering organization. Facebook doesn't have a news-gathering organization. The actual facts come from mostly old organizations plus a few people on the ground with video. But that's different. That's raw data. I think that YouTube is sort of best, like TikTok is best, when it's showing you raw data. It galvanized people somehow because it felt real.

MERING Everything online with what you can witness in Gaza is extremely techno-dystopian. All that raw, intense, traumatizing information in between memes and funny advertisements–I can understand the cognitive dissonance and the pain of witnessing that information unprocessed.

CURTIS I was reading about a woman in Odesa who can't sleep at night because she's terrified that the Iranian-made drone above her sent by Russia is going to drop a grenade into her window. It's like some weird 1980s cyber-tech novel. Drones were invented by Israel in the ‘70s. Iran makes drones, sends 'em to Russia, and a woman in Odesa gets a grenade dropped into her window. It's strange. But what I'm saying is that fragmentary strangeness is what is going to galvanize the next politics because there is no map that explains it.

MERING My theory about our culture is that we're weirdly frozen within the 20th century. The movies, and the media, and everything are convincing us that life is still that way. But I think that it changed so radically and so dramatically so long ago that when people catch up to the idea of how different things are, instead of creating a new map, they’ll be grieving this death. There's a lot of grief in the process of realizing that movies and plot lines of TV shows have a bigger impact on our concept of reality than we're willing to admit.

CURTIS There's a melancholy to a lot of the TV culture at the moment and in the stories. For instance, The Last Of Us. It's melancholic: we are the last people on Earth.

MERING It is strange. And there aren’t a lot of comedy shows because people aren’t sure how to be funny.

CURTIS I have not a cynical theory, but a sort of ruthlessly practical theory. I find it very strange that the class of which you and I are also a part—who are well-educated, liberal-inclined, nice people—we are the most narcissistic group ever in the history of the world. Individualism has gotten to this incredible stage. We've also decided that we're the class that is going to witness the end of the world. It has a terrible, deadening effect on the idea that you could actually do anything because you just think, Oh, the world's going to end. I don’t know whether you find that in America, but here in the UK, the climate movement, which I always thought should be fighting to make a better world for people, is paralyzed by a sense of apocalypse.

MERING I really think that what people deal with nowadays—with the way the economy works and how you make money—if you don't have the support of your parents and you're just out there on your own, you have to become a pirate. At a certain point, Peter Pan goes away and your youthful idealism about politics might shrivel in light of the reality of making enough money to feed your kids. The crushing weight of even trying to achieve that middle-class life that our parents might have had is in itself a big enough distraction. It does leave the idealism for the people who are living a little bit more comfortably, which definitely adds to the dissonance.

CURTIS Here and in Europe there is a big backlash against the climate movement coming from the working class, because they are, for the first time, being told they're going to have to pay. They're going to have to buy more expensive cars, get rid of boilers for their heating, and install complex heat pumps. And the liberals running the climate change movement have been dealing with it in an almost dream-like technical way. There's a woman called Sahra Wagenknecht who just formed a new party last month in Germany, which is left-wing in all kinds of economic ways, but culturally quite conservative. It's already got 23% of the vote behind it within a month. Over the last twenty years, people at the top have done very well and people at the bottom have gotten much poorer, and they are very frightened. This all goes back to not understanding the reality of the modern world. Not having a map. You are up against raw power.

MERING This also would make the map so much more important because power has been so weirdly decentralized to hide itself. It's not necessarily one thing. It's this myriad of different cumulative forces. So, it's even harder to sniff out where the energy should be put. There was a moment in America when garbage was not the citizen's responsibility. If a company in the 1920s started making disposable products, it was the company's responsibility to deal with the detritus that would come from those disposable products. And the companies won something in the Supreme Court that said the consumer is ultimately the one that's responsible. This sentiment carries through now to this idea of cleaning up the planet. That it’s the consumer’s responsibility. And that's completely wrong.

CURTIS It's presented as empowering, but actually, it's totally disempowering. Did you know that the idea of the carbon footprint was invented by British Petroleum around 2005? It was a way of turning attention away from the fact that, actually, the reason why a 35-year-old mother has to drive 40 miles to work is because of the kind of society they are told to live in. So, it's not their carbon footprint, it's a society that has carbonized itself in a particular form that forces those people to actually behave in that way. But they are blamed. I think what I'm saying is that the radicalism of now is going to actually deal with raw power.

MERING Do you feel like the first step towards reclaiming that power is admitting our powerlessness?

CURTIS There are so many powerful groups within the media that are actually clashing over this. Suddenly, power comes back into focus. I remember a member of Parliament saying, “I don't think anyone knows where the power is any longer. I know that I've got no power.” But then, you talk to a journalist and say, “Well, you've got the power.” And he goes, “No, we haven't got any power. It's the bankers who've got the power.” And then, you go and talk to a banker and the banker says, “Well, we sort of have power, but actually we're just slaves to this crazy market that just goes up and down all the time. We don't know who's in power.”

MERING I mean, maybe the tech guys in Silicon Valley have the power.

CURTIS The other people I've gotten interested in recently are called short sellers. They're the people who now go and research big companies and find out what's wrong with them, publicize it, and bet that the shares are going to crash. So actually, the people who know the most information in the world are no longer traditional journalists, but people who want to benefit from disaster.

MERING It's a society of pirates.

CURTIS Hustlers and grifters have the power. But then, they would say, “Well, we do, but we don't know what we're doing with it. We're just making money out of it.”

MERING It's interesting to think of this idea that there was a time in America when education was quite good—before a lot of the neoliberal financial policies. Do you think that was when they knew where the power was? Was that a time when people were more accountable for their actions? Or has it always kind of been a pirate hustler mentality in power and the difference was the strength of the myth, which is now falling apart?

CURTIS I'm gonna weasel out of that one by saying that myths always create reality. I mean, you are right. There was a period, I presume, from the 1920s through to the 1970s when people thought they knew where the power was. Politics had more control over the economy, and they would stop a lot of the corruption. That's not to say there wasn't corruption. If we talk about America, it's going to have to look back at how the Vietnam War not only tore the nation apart in terms of morality and politics, but also the shock waves from it that led to a shift in power. No one quite knows how that happened. Out of that came inflation chaos, a new kind of left-wing politics, and actually, it was the death of left-wing politics. And out of that came a sort of crazy individualism, which we are now at the end of.

MERING When Columbine happened, it was this huge historical moment of horror. How could this possibly happen? But then, the shootings became more common and they just kept happening. A real strong desensitization started happening, almost to create this feeling of post-history. I feel like the reaction to Sandy Hook in the ’60s or ’70s would've been so different than it is now.

CURTIS It was a turning point because that was when the apocalypses began. There was 9/11, there was the war in Iraq, and then there was the financial crash in 2008. In the past, journalism's job was to go and find out bad stuff and then it told the people about that bad stuff, so we would then put pressure on our politicians and lawmakers to change things. That didn't always work, but it sort of worked. Nowadays, if I'm just being a typical reader or a watcher of news, if I see someone telling me something terrible, I'm not interested because I think, Yeah, well, everyone knows that happens and everyone knows that nothing's gonna change. If I read extraordinary evidence of how practically everyone who is in power in my country hides large amounts of their wealth abroad illegally, I go, Yes … and? To go back to the idea of having a new map, investigative journalism no longer has any traction because it tells us terrible things and nothing happens. Journalism should now be telling us why nothing happens.

MERING Well, I think that's what you're trying to do. And that's why I was so attracted to your work. Here's somebody that's actually trying to break this all down for us and go behind the curtain and say, “Look, there's a wizard behind the curtain.” (laughs) I really think your documentaries are more like maps. Even in their structure, they're kind of non-linear. It’s a more holistic approach. You combine philosophy and history and speculation into one. I definitely see younger people realizing there's more to it than meets the eye.

CURTIS That's what journalists should be trying to explain. That's partly what I try to do, but I still think a new political movement is going to have to do that. To return the compliment, I think what you do in your music reflects how people navigate their way through the world at the moment. Every age has its own type of realism. You are evoking that feeling through a series of moods. Because that's really how people navigate now—they have emotional reactions to situations or places that resonate with them. And sometimes they link that to the past, which is where nostalgia lies, which is both very strong and also very destructive. It’s almost like that gives them security. And it gives them a sense of, not tradition, but being part of something that feels like it’s from the past. It’s also like a terrible ghost calling them back, saying, “Come and live with us now. Forget the now, just come and live with us.” Someone said something terrible to me the other day. They said, “If you watch a lot of the archives of comedy shows on YouTube, you are listening to the laughter of the dead.” So, there’s a modern ghost story about culture.

MERING How do you feel about Mark Fisher’s theory of hauntology—his idea that we're haunted by the future that we never had?

CURTIS I agreed with him. I mean, we used to meet and talk about this actually quite a lot. You know, he killed himself. His observations of the nostalgia in British music was very good—that sense of an old power that had gone within contemporary music. Every age creates its own ghost stories, but we don't seem to have created the right ghost stories. It's something to do with modern culture. I have a theory that AI has nothing to do with the future. AI is simply about giving machines masses of culture from the past and letting them read it and regurgitate it to us in new forms. We are living in a haunted house is really what I'm saying.

MERING We're still living under the umbrella of this myth. Like with music—there are a lot of times in the industry where music is still treated as if it impacts culture and society. I don't know whose job it is to keep that myth going, but it must be serving some purpose. Do you think the purpose is distraction or to keep the haunted house alive?

CURTIS I think it depends on where you are in the society. It's a comfort blanket in the face of everyone telling you that the future is dark. If you are a politician or someone in a position of power, it's a way of disguising the fact that you also have no idea of the future anymore. It performs all kinds of functions. And it is divided into two kinds of people. There are people like Taylor Swift who try to take the chaos and turn it into nice little stories so you can recognize yourself in it, which sort of makes you feel safe. Then there is what you are doing, which is trying to give a feeling of what it's like to move through it. If you are an AI computer learning, you are fed billions and billions of images and things to compute. Well, that's exactly what we are being fed. And to be honest, I'm one of the worst offenders. I take old footage and repurpose it. Of course, I do it to say something about the modern world. But we are stuck within a haunted house and some of us are trying to find the way out, or at least draw a pathway to the door out. Others are just relishing a haunted house.

MERING I do think nostalgia is a perfect tool for capitalism. I see that with my generation—the way they repackaged the ’90s for us. This pre-cell phone era. It has leaked into fashion. I just see how nostalgia is taking advantage of this sickness and yearning and capitalizing off of it.

CURTIS In modern physics, their latest theory after multiverses, is that time doesn't really exist. It’s as if we're in a terminal station where all the trains are coming in from the past and just dumping stuff, whether it be from the ’90s or the ’60s or the ’50s. If you are what's called Generation Alpha, the people who've actually grown up with social media, you have no sense of a historical timeline. You live in a swirling matrix of all these trains coming in from the past and just dumping their stuff.

MERING Do you feel like we're all voyeurs looking back at different eras? Pagan time travel is what I call it.

CURTIS It's time travel without a purpose. But I think there will be parts that are going to crack—with Gaza, but also with what's happening to the climate movement. When it comes up against people's financially difficult lives, it's going to reawaken the sense of power and purpose. And when you challenge power, you have a purpose. And that leads to thinking about the future. I mean, you can't go on repurposing and replaying culture, can you?

MERING That was Mark Fisher's fear—that we would be stuck in this infinity loop; hitting the same note over and over again. Because that was the last note of authenticity before everything was splintered into a million different fragments from the internet and technology. But I do think the biggest hurdle, like you talked about, is drawing a map and finding out where the power is. It’s like we haven't fully addressed the widespread sense of grief.

CURTIS Someone showed me a video game called Red Dead Redemption the other day. In the game, you are riding around this beautiful world on your own in 1900, or whatever. It exquisitely rendered this sense of melancholy that people have now as they're traveling around the world pretty much by themselves as if there's no future. In this country, I always thought the melancholy, especially in my class, is due to the loss of the empire. And Britain may disintegrate even further. In America, there is that deep melancholy, but I don’t know where it comes from.

MERING My theory is that it represents the disparity between our belief in what the world should be and what it actually is when we're confronted with reality. For my generation, it’s growing up with the idea of being able to buy a house and build a family.

CURTIS I think that's true here. If you are ever going to buy a house, you are going to be in debt to a large financial corporation for the rest of your life. And that is going back to something way before democracy. It goes back to feudalism, when the Lord of the manor owned the cottage you lived in, and you would live there indentured to him for the rest of your life. There is this sense that you've somehow gone back in time in this country. It's quite weird. You've got this nostalgia for an empire, but also the fact that you've gone even further back in time to an old system of power and you have no idea how you can confront it. Because how do you confront a large financial corporation in which your pensions are probably invested and your parents' pensions are invested? It is really complex. No one has got their head around it and I think that leads to a deep melancholy as well.

MERING It's really interesting to think about a time when people were exposed to less information. This younger generation—the amount of information that they're bombarded with, it must also be a source of melancholy.

CURTIS Speaking as a journalist, one of the things journalists learn very early on is: don't overdo the information. It'll stop you from turning it into a narrative that will connect with the people. You can go back and check and add stuff on, but just don't overdo it.

MERING How do you narrow it down for yourself?

CURTIS You find the stories that inspire you. I take the view that I'm quite normal and if I find a story that connects with the way I am feeling about the world, I'll think, Well, probably that's what other people will connect with. It’s the same with the music I use. You edit stuff on the basis of what you genuinely react to, rather than another piece of information that seems to be relevant but actually in your heart of hearts, you think it's quite boring. You've got to create an emotional story that will grip you and therefore other people. That's what good journalism is about. This is why I don't think journalists create maps. I think people who challenge power create maps because they can see a way of taking the stories people like you and me tell, and the moods that people like you and me create, and they go, Oh yes, that connects with the way I'm feeling at the moment. I've always thought that if what you're making doesn't actually vibrate in the back of your head, you shouldn't do it. The way reality is described by most journalists does not connect to that humming thing.

MERING Last question. How do we imagine a future through the lens of levity? How do we put values and meaning into things so it isn't this grief-stricken process?

CURTIS One of the things I have been thinking about is making a film, and I would give it the title, Apocalypse Now And Then. It would look back at all the events from 9/11 onwards. I suppose levity is a way of doing this, but you want to pull back and make people look at these events again. At the moment, we have accepted ways of dealing with 9/11, the financial crisis, Trump. They've become so accepted that people don't even look at them anymore. So, using levity, I would be pulling back and saying, we fetishize apocalypse. So much so that it's being used as a comfort blanket and a way of disguising the fact that we have no idea how to change the world for the better. Apocalypse Now and Then would not make light of apocalypses, but it would be irreverent about them. Do you believe in levity, then?

MERING I do, but I might be more on the emotional side. If I can just break everybody's emotional shell just a little bit and get to that gooey center of humanity, that is where the biological internet is. That's where we can feel the interconnectivity and the empathy. As an adult, keeping your empathy gets harder. Maybe you are born with that membrane being a little thinner. As you get older and you learn how to protect yourself, the membrane gets a lot thicker. The idea of levity I might be interested in is learning how to cultivate a naïveté and innocence, to not become so desensitized. I think keeping hope alive is a sense of levity, even in times where it seems preposterous or very ignorant. I'm always using humor. That's my form of levity: respectfully trying to laugh at the spectacle.