interview by Summer Bowie

photography by Damien Maloney

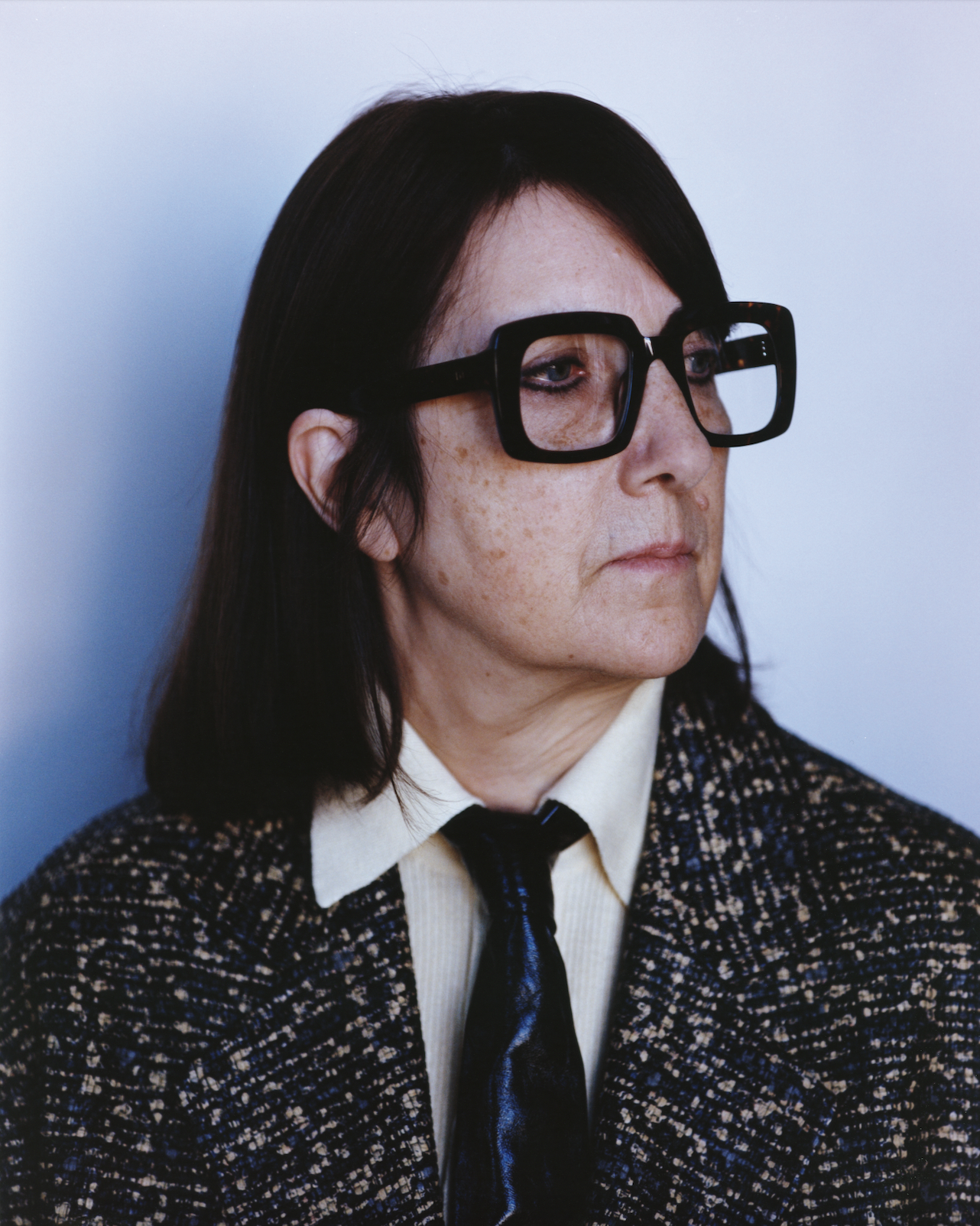

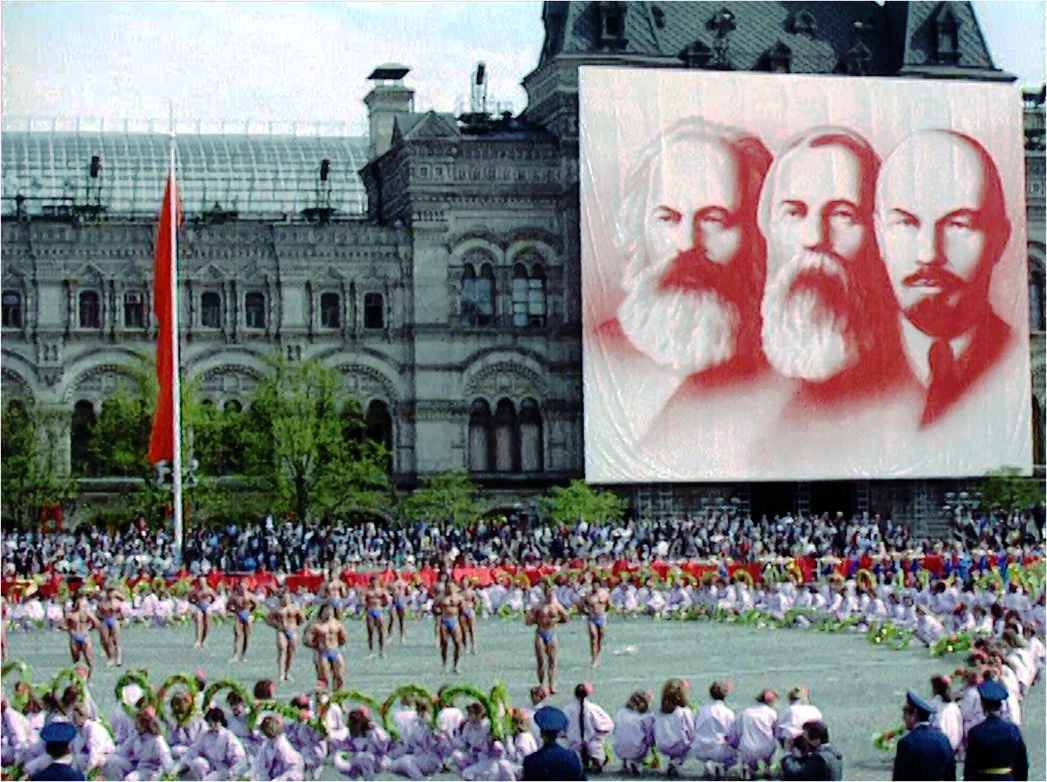

The playfully disturbing works of Polly Borland have an uncanny way of tapping into our inner child’s psyche. Her recent foray into sculpture features abstract animal and humanoid forms that challenge notions of gender and beauty—themes that were foundational to her early photographic works and have remained central to her oeuvre. Born and raised in Melbourne as the third of seven children, Borland lost her mother at the age of twenty-one and was thrust into a maternal role within the family while navigating a burgeoning punk scene saturated in violence and addiction. Her early work was regularly published in Australian Vogue and her career as a portrait and reportage photographer quickly gained momentum after she moved to London in 1989. In 2001, her first book, The Babies, turned a motherly gaze on a cohort of infantilism fetishists with an essay by Susan Sontag, effectively establishing her as a proper art photographer. Shortly thereafter, she was selected as one of eight photographers to take portraits of Queen Elizabeth II for her Golden Jubilee. Following several books of photography that muse on surrealist themes of ego, eros, and pathos, Borland finds herself living in Los Angeles using models to create soft sculptures that are 3D scanned and cast as hard sculptures in a puckish improvisational process that is layered with an amalgam of discreetly suppressed memories from her youth.

SUMMER BOWIE I want to start with you first picking up a camera. I think your dad gave you your first camera.

POLLY BORLAND Yes. I was doing art history in Australia, and at the time, it had to accompany a practical art subject, but I didn’t feel like I could draw. So, my teacher said, "Well, why don't I build a darkroom in the closet and you can take photos?" That’s when I started taking photos, and the minute I started, my father lent me his camera. It was a Nikon 35mm and I was shooting originally in black and white. I absolutely loved it. I could edit, control, and curate my environment. I was always, from the get-go, photographing people. My sisters were models, my friends were models. And so, the final two years of my high school life were spent taking photos as well as other academic subjects. Then, I decided to apply to a photography college. I took a year off, and worked shitty jobs, and lived at home. I was only interested in photographing cool things or cool people. And so I used that year to get a folio together, and get into an art school. I got in and never looked back.

BOWIE Would you say that your discovery of the adult babies was a foundational step in finding a subject that combines so many of your interests and your approach to documentation?

BORLAND Well, that was the thing, the subject matter was hugely important to me, but I was also very interested in making photography less about reality and more about painting, almost. For me, it was the light, and the framing, and the texture—almost taking away the photographic element. During art school in Australia, I went to an exhibition at the Photographer’s Gallery. It was Larry Clark before Larry Clark became a thing. And there were these photos literally pinned to the wall. You could see all the scratch marks. And then, the subject matter of teenage lust in Tulsa. I'd never, ever seen anything like that, even though I was surrounded by heroin users. There's something horrific about those photos, but also very seductive. I liked the push and pull of that. Diane Arbus, for me, was similar. People like to say that she was very cold, but her photos are very human to me. I think there's a deep connection between her and her sitters. They're up close and personal.

So, the subject matter was always key, but it was also the craft or the art involved in elevating them just from being documentation. I think a very formative influence for me was the Mary Ellen Mark photos of the working women in Bombay. And there was that book Nicaragua, from Susan Meiselas where there's a stylization of color and drama in the lighting. Everything is fused to make something that transcends just a document.

BOWIE There always is a degree of power that you have as the photographer. With the adult babies, they were allowing you to document them in states of extreme vulnerability, which meant that they had to trust that you weren’t going to exploit them for other people's entertainment. Most of us don't know what it's like to want to wear a diaper and have it changed by another adult. But there's a humanity that you bring to those images where we can connect with the inclination to be taken care of.

BORLAND What I realized quite early on was that the camera gave me license to go into other people's lives. All human beings are the same, some just have more power than others. But people like attention. Not everyone, but it's a general rule that I instinctively knew. The leap from my school years was that I found myself living in England, and I was doing portraits for a lot of the magazines. Then I discovered the adult babies through a friend, and it really felt like I had died and gone to heaven when I went there. These giant babies are crawling around the floor. It was a mixture of pathos. It was very carnivalesque. It was surreal. All my favorite things all wrapped up into one. Originally, I photographed them for The Independent in London, and they were obscured by masks. But then, we established a level of trust and they took off the masks when we shot the book. We talked about it a lot, and they liked the attention they were getting from me. I would say for most photographers behind the camera it's an intense gaze. So in a way, I was replicating the mother's gaze.

BOWIE Was this before you became a mother yourself?

BORLAND The book came out in 2001, just before I had Louie.

BOWIE So, you were just about to become a mother when you released the Babies book. There’s a similar vibe to the Bunny book, in terms of this very gritty approach that also feels very childlike in its playfulness. However, this was the first time you started to work with stockings, which have been a theme within your work ever since.

BORLAND Yes. Basically, I'd seen Gwendoline Christie walking around Brighton, where I lived in England, and she worked in a knick-knack shop called Pussy. Gwendoline was very tall. She looked like a 1950s starlet. And I had had a child, so suddenly I couldn't do all my traveling, and I really was just trying to focus on my own books and exhibitions. And so, the original idea for the photos with Gwen was a series of Bunny Yeager-style pinup photos. But, quickly, that idea got tired. It was a five-year project with Gwen, so it just kept evolving. She went off to drama school and she'd come back on the weekends. We slowly realized that we were using a lot of different feminine clichés and turning them on their head. The stockings came about because I was trying to turn her into a doll. In the ’70s, and even earlier, you could get dolls that had painted stockings, and Bunny obviously feeds into the whole idea of the Playboy bunny, Bunny Yeager, the pinup. And then we did cat photos and horse photos. It was everything you associate little girls with, but we'd always subvert it in some way. The more she was doing her drama course, the more playful the photos became.

BOWIE You guys were playing so much with humor and pathos.

BORLAND Take Charles Laughton in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), or Diane Arbus, any of her photos, they have this incredible pathos in them. For me, in particular, there is an interest in childhood and the loss of innocence. Pathos can move you in ways, like Fear Eats the Soul (1974) by Fassbinder. I can name many films that just have so much pathos for me. If I was to achieve anything, it would be that pathos in my work. There is always that clash of the beauty and the innocence with some kind of horror, some kind of jarring element.

BOWIE It's the impending killer of that innocence, right?

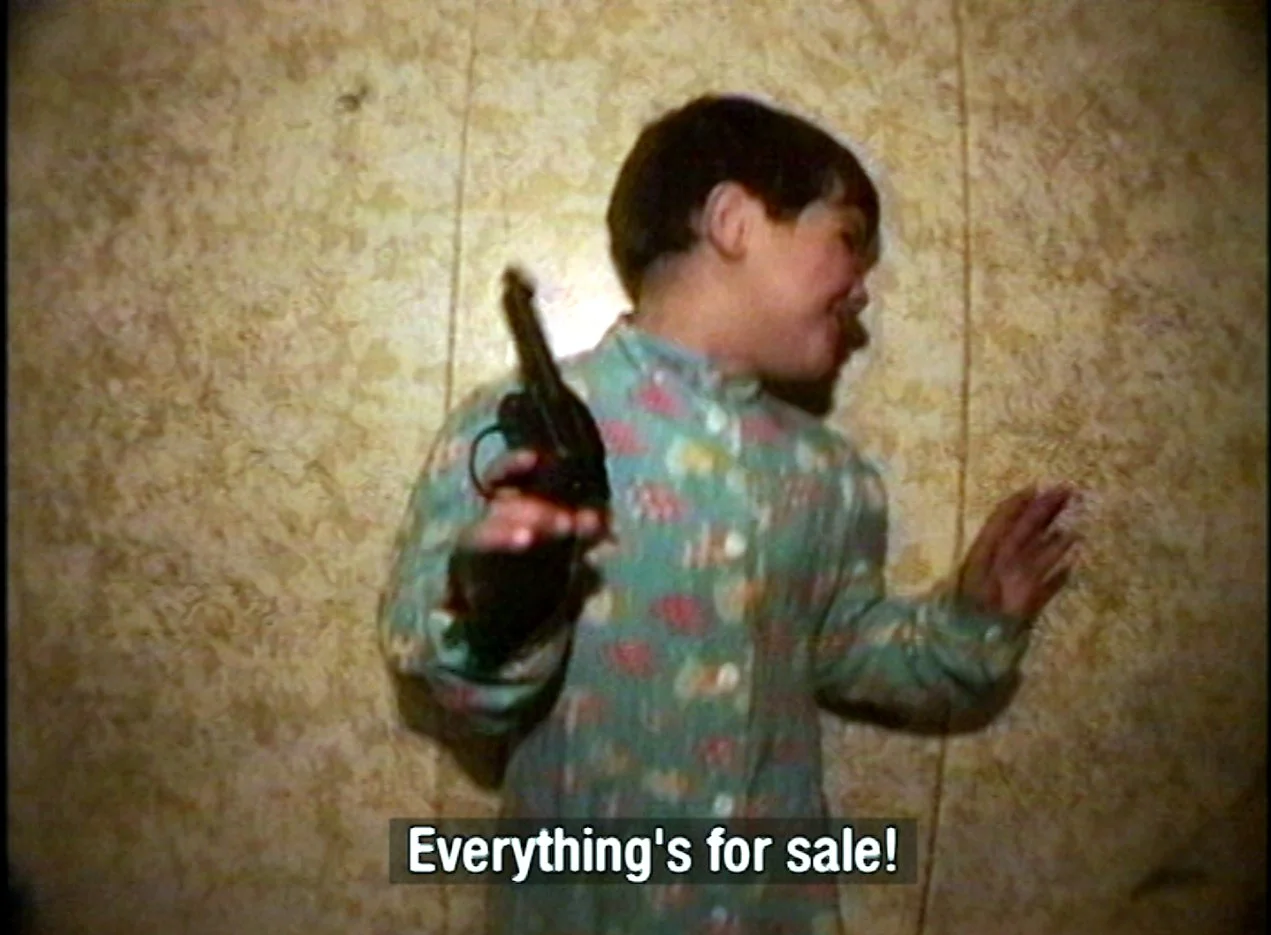

BORLAND Almost interrupted innocence. I'm sure some people just went through childhood and it was maybe an easy transition. But for others, there are outside circumstances that can come in and rob children of being children, like the death of a mother or adverse people within the family. It's not just an awakening for me. The loss of innocence is circumstantial. It’s as physical as the environment. As a teenager, you realize the world isn't as friendly as you would have liked it to be. It's a kind of interruption that is more omnipresent than defined. If you look again at the Larry Clark photos, you think, People live like that? People can embrace that lifestyle with guns and needles in their arms, and a lot of them are young. Those situations are not just found. It's like outside forces have come in and disturbed.

BOWIE It seems to me to be the overall entropy of life. At some point, these outside forces are beyond our parent’s or community's capability to protect us and we have to confront them because life is not completely safe.

BORLAND Yeah, and if you go back to where I was right at the beginning of the conversation, photography for me was creating, curating, and controlling.

BOWIE You can, at least temporarily, create a space where the chaos has parameters.

BORLAND But at the same time, when people view the photos they don't necessarily feel safe.

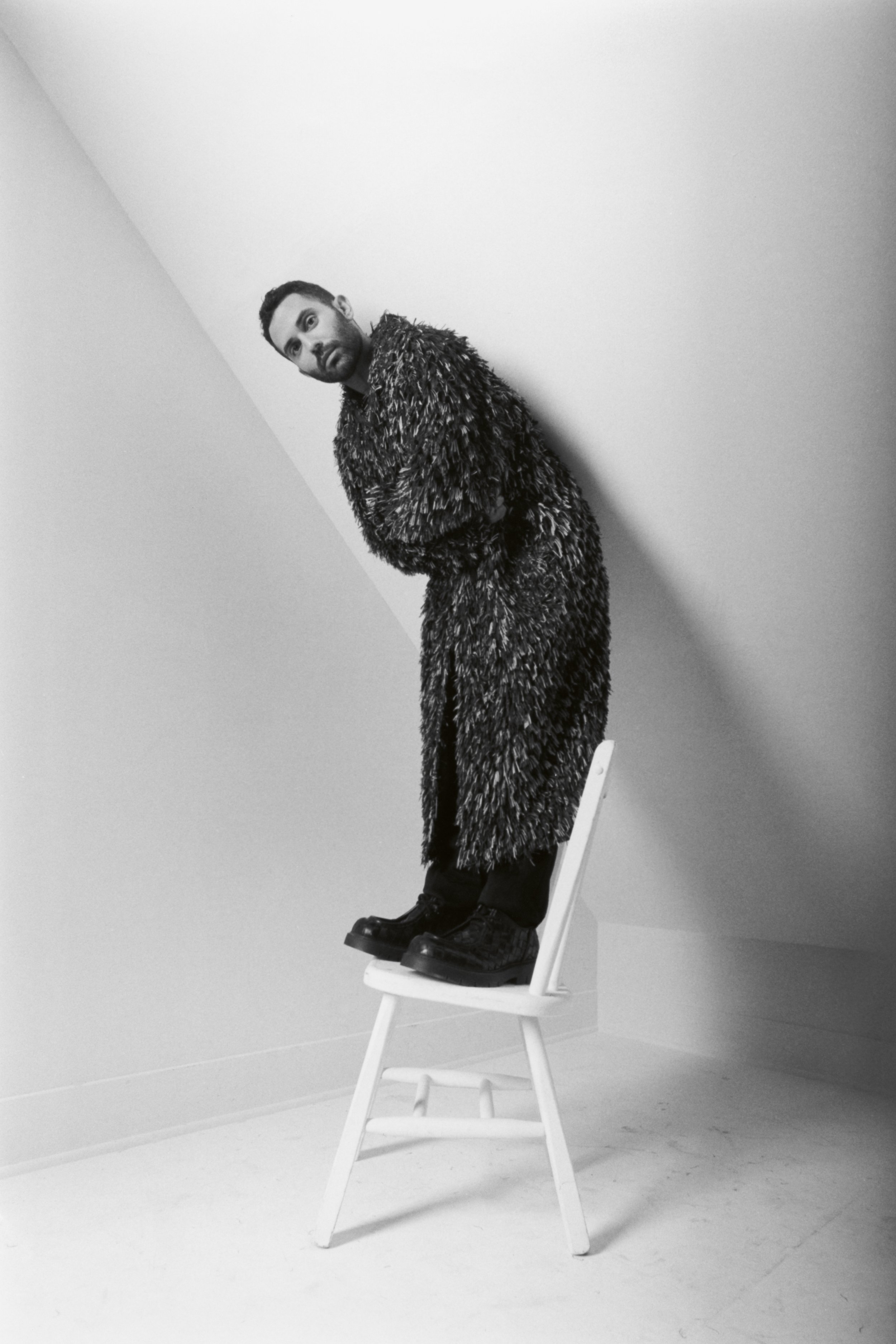

BOWIE Sure. But it’s like BDSM, there are safe words and protocols between all parties to create something that looks like trauma, and yet when done ethically, there is full control over the degree of pain, and what direction it goes, and how it all ends. Where the frame is held—which goes into what I wanted to ask you about the Smudge series, where you worked with three subjects, one of which being your good friend Nick Cave. In reference to that series, he said, “I had to give myself over to this process of being degraded, initially degraded and there was quite a beautiful thing that happened out of that.” It’s as though you inspire a level of liberation for those who are willing to submit themselves to this sort of infantile play.

BORLAND Well, he liked the fact that he didn't have to think. It was interesting because the first day he gave himself completely over to the process and there were no mirrors in the house. He couldn't see what costumes I was putting him in and what I was doing. I think he quite liked the sensual feel of the leotard and the Lycra that I was putting him in. He found the whole thing very sensual. He also just gave himself to the process, he didn't have to think he wasn't in control. Which, if you know Nick, he's a control freak. But he came back the next day and he'd been thinking about what I'd been doing, and had real doubts. He became really self-conscious and the second day was not easy.

BOWIE I love being in the sensory deprivation of your costumes. You’re so in the moment that you are sort of delivered from your ego. When we're capable of looking in the mirror, or at the screen with digital photography, there's too much control. And if you can't lose control, then you can't feel that liberation at all.

BORLAND The thing that interested me about photography when I started, and for years this kept me captivated, was the delay between taking the photo and getting the film, not really ever knowing what I got until I saw it. It was very instinctual. You had to go off of how you felt. When I was dressing you up the other day for a sculpture—which is what I now do—I get that excitement. That excitement that I was feeling was what I used to feel. In photography, with forty years of experience, I know what works and what doesn't work. There's always an element of surprise, but you go on how you feel. It is magic, photography. When you do it the old-fashioned way.

BOWIE Recently, for the first time, you stepped in front of the camera and allowed Penny Slinger to shoot you. What did you learn in that process of being on the other side?

BORLAND I loved working with Penny, and I felt uninhibited, which my whole life I've been very inhibited in my own physicality. The only way I could get to the point where I could do that work with Penny was because I'd spent a few years photographing myself for my Nudie series with my iPhone, and the minute that work went out into the world, I knew that I had gotten rid of any attempt to cover myself up in any way. But the Penny work freed me in order to get in front of somebody else and be photographed. What I did find hard, which Gwen found hard, was then you have to live with the photos and you have to be okay with them being out in the world. But I think it's necessary. We're living in pretty dark times. And I've never been afraid in my work. The things that have informed me and my life have been people that are really unafraid. So, Penny and my work is really important work. It's not pretty. I've got a whole thing about ugly and pretty. I like things to look beautiful, but I like the jarring.

BOWIE We all have demons that we need to exorcize. Gwen needed to find acceptance for her unusual height and unique body type so that she could develop the confidence to go on and become a big actor. But once you're liberated from those demons, you want to believe that you never had them to begin with. Other people do it in therapy, but for artists it's often public domain.

BORLAND Yeah. It’s very cathartic. If you look at all the work I've done over my lifetime, one thing has always led to another. It's never staying in the same place. Someone said to me the other day, "It's hard to be good at one thing, but when you're good at lots of different things, people find that confusing." I have kept changing, but thematically all my work is about the same things.

BOWIE There's a very clear continuum. I read that your Morph series were originally going to be hallucinogenic mindscape experiences, these sort of pre-conscious creatures that eventually evolved to have human-like qualities. Were you originally attempting to transcend the human condition?

BORLAND Yes, exactly. And I have got a film. It's called The Morph Movie. It has only been shown at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. The Morph series was definitely meant to transcend the human experience. I just wanted to strip everything away from that work, like the eyes, the mouths, the noses. It was also rooted in Doctor Seuss and Dumbo (1941) as well—that surrealist, childlike, dream effect.

BOWIE That’s really where your photography started moving into sculpture.

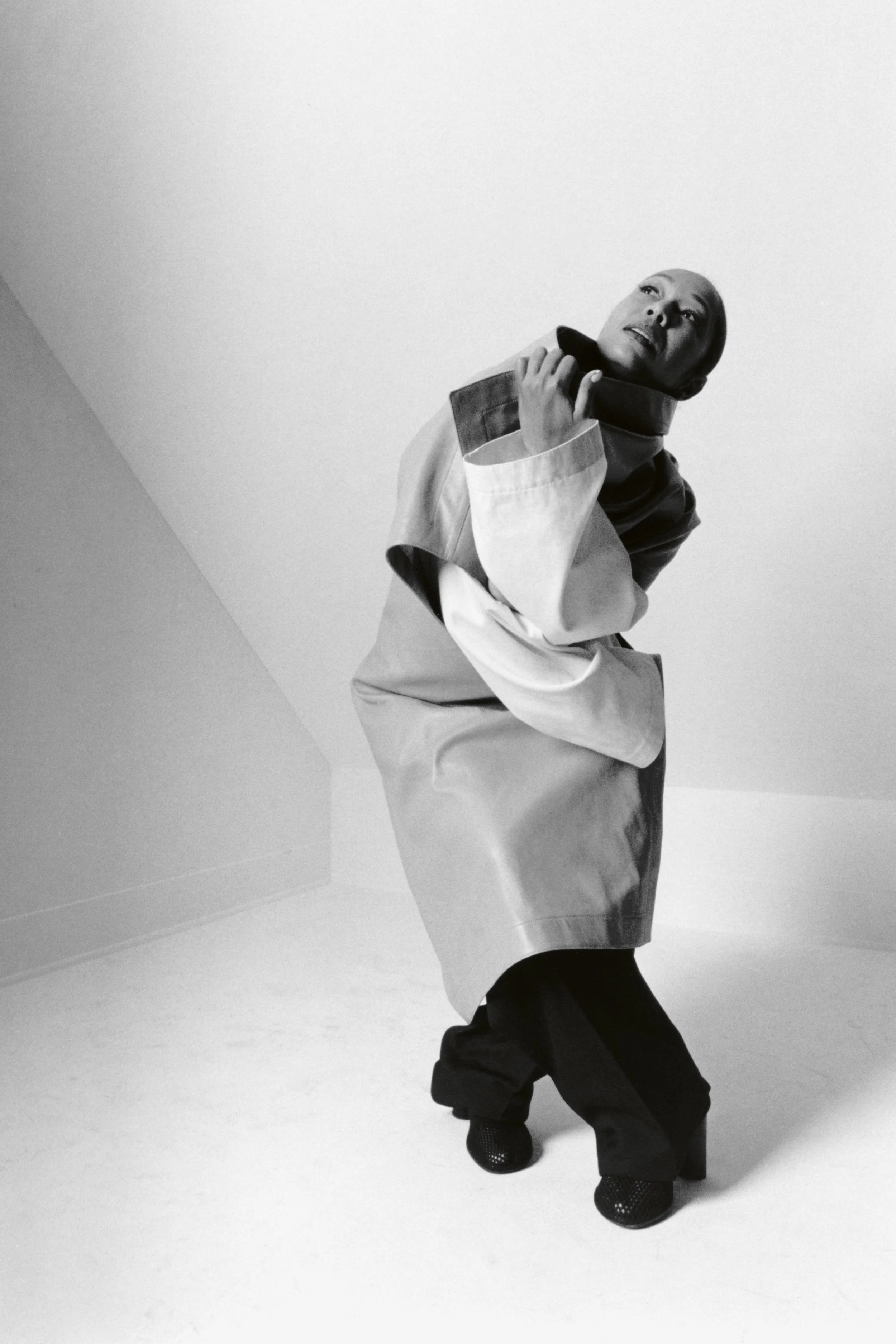

BORLAND It was all because of a chance meeting at a tiny art event in this little country town. I met Dan Tobin from a foundry called UAP in the middle of Covid in the outback in Australia. He just said, "You've been making sculpture in your photos, and we want to take the sculpture out of the photos and put it into the real world." It revitalized my relationship with my work. Because it's given me a whole new playground to play in. I'm in my sixties and it's like I'm starting again. But it makes sense as a thing for me to be doing if you look at what was happening in my photos, it was all costumes.

BOWIE And there's this connection with the animal play and the Bunny series, because many of them start to become these scrutable animals. Is that something that you plan ahead of time, or is that something that happens in the improvisational process?

BORLAND That happens in improvisation. And like with Gwen, we were coming up with ideas and then I'd get props or bits of costumes and have ideas, but a lot of how I work is in the moment. I did do some drawings before I dressed you yesterday. I've got this weird drawing with big bosoms and a big bum, so it's pretty much how I imagined it, but I don't always pre-imagine. A lot of the time the session will take me to a different place. That's how I used to photograph. There's a whole visual logic to how I think and it's very rooted in the imagination. Also, I think I'm conjuring up visual references from my childhood in a lot of ways.

BOWIE You approach sexuality in a very playful way. There's always these breasts, and asses, and penises, and vaginas, and sometimes they're where they should be, and sometimes they're where they shouldn't be. I got such a kick out of seeing the sculpture after I came out of it. There were these huge labial folds that were created by the stockings. But why is sex so funny?

BORLAND Well, I actually don't know if I think it is funny. I think it's deadly serious, actually. But, I feel like I was playing with the non-binary, the genderless. The non-specific, but also the very specific. Mixtures of the binary genders way before we even started having these discussions. I remember as a child, I wanted to be a boy. I was obsessed. I used to have this gorgeous little pillow for a baby that was very soft. I used to stuff the pillow down my pants to pretend that I was a boy. But I also became aware from a very young age that boys were more empowered than girls. So, it was a bit like, fuck you, I'm not playing that game. I never really felt like I fit into a feminine type or what we were all told was a feminine type. Those are hints to where it comes from, but at the same time, it's just playful. I also don't necessarily want it to be easily digested.